Labour’s Muslim vote: what the data so far says about the election risk of Keir Starmer’s Gaza position

The Muslim vote

There are 20 constituencies in the UK that have an electorate comprised of more than 30% Muslims. All of them elected a Labour MP in 2019. At the top of the list is Birmingham Hodge Hill, where 62% of the population identifies as Muslim.

In Bradford West 59% of the population is Muslim, in Ilford South, 44%, and in Leicester South, 32%. Rochdale ranks 18th in the list of the 20 constituencies with the largest proportion of Muslim residents. Interestingly enough, just under 19% of the electorate in Holborn and St Pancras, Keir Starmer’s constituency, identifies as Muslim.

There are currently 199 Labour MPs in the House of Commons – a slight reduction from the 202 who were elected in 2019. A bare majority in the House of Commons requires 326 MPs and a working majority more like 346. The party clearly has a mountain to climb to achieve that, even with a lead of around 20% in current polls.

So Starmer will certainly be asking whether Labour can still expect to win seats with a high proportion of Muslim voters in a way that it has done in the past, given what happened in Rochdale. He continues to equivocate over the deaths in Gaza and still follows the government’s line on the conflict, despite it being essentially a colonial war.

Historically, Labour has had a long tradition of anti-colonialism. After the second world war, it was a Labour government that began the process of de-colonisation in the British empire by giving independence to India in 1947.

When is a safe seat not a safe seat?

There is an argument that constituencies with a high proportion of Muslims are relatively safe Labour seats. This is evidenced by the fact that they remained in the Labour camp even when the party suffered a heavy defeat in 2019. The implication is that if anger over Gaza is confined to Muslims, then it is not going to affect the number of seats won by Labour very much.

However, concern about Gaza is shared by people other than Muslims. Polling from YouGov conducted last month shows that there has been a distinct shift in British public opinion about the war since it started. More people are calling for a ceasefire and fewer see Israel’s attacks on Gaza as being justified.

Protesters wearing masks call on Starmer to support a ceasefire. Alamy

Protesters wearing masks call on Starmer to support a ceasefire. Alamy

There is clear evidence that younger voters, in particular, feel more sympathy towards the Palestinian cause than the rest of the population. This is also a group that heavily supported Labour in the 2019 election. While young people in this group are unlikely to switch to voting Conservative over Gaza, the concern for Labour will be that they might abstain in the next election.

How different religions vote

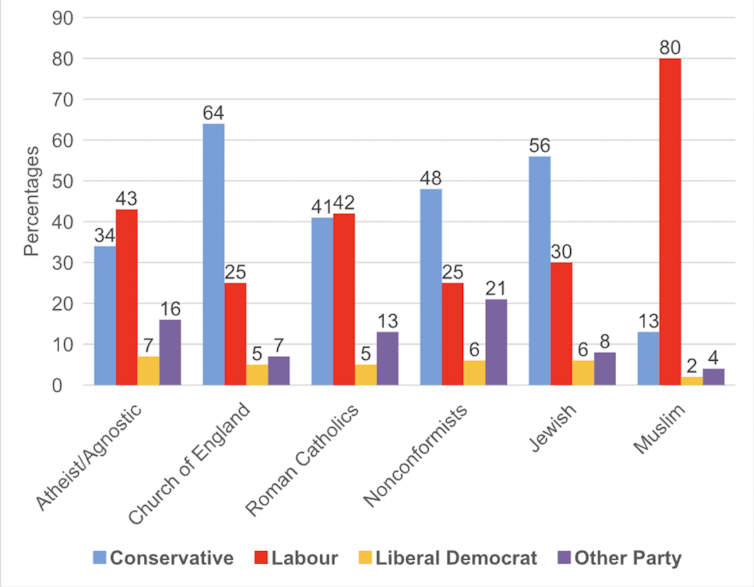

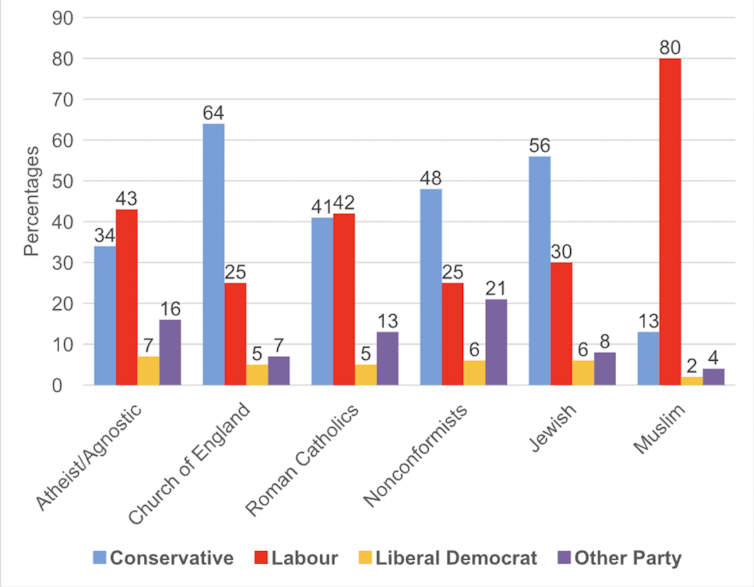

Starmer’s reluctance to call out what is happening in Gaza is a puzzle, since Muslims are overwhelmingly Labour supporters. This can be seen in data from the British Election Study online panel survey conducted after the 2019 general election. The chart shows the relationship between the religious affiliation of the respondents and their voting behaviour in that election.

Religious Affiliation and Voting in the 2019 General Election:

How religious identity maps onto party preference. British Election Study, CC BY-ND

The Church of England used to be described as the “Tory party at prayer” and it clearly remains so today, since 64% of Church of England identifiers supported the Conservatives compared to just 25% who supported Labour.

In contrast, Roman Catholics were marginally more Labour (42%) than Conservative (41%). Nonconformists were similar to Church of England identifiers with 48% Conservative and 25% Labour. Meanwhile, 43% of atheists and agnostics supported Labour and 34% the Conservatives.

Jewish voters favoured the Conservatives by a margin of 56% to 30% Labour. Finally, Muslim voters favoured Labour by a massive 80% compared with the Conservative’s 13%.

If anger over the Gaza war is confined to Muslims it is not likely to influence the outcome of this year’s election. But it is worth remembering that this is not the first time Labour has been damaged by events in the Middle East.

Support for Tony Blair was greatly weakened by his decision to invade Iraq in 2003 at the request of the then US president, George W. Bush. He has never really lived down the reputation he acquired for this mistake.

There is not yet evidence that Labour’s position on Gaza will cost it a majority in the election but the strength of feeling on this issue is growing and the future is not certain. With hundreds of additional seats needed, Starmer can’t afford to take any for granted. The risk of losing these voters to the Conservatives is marginal but the risk of losing them to apathy and disillusionment should have him reconsidering his position.

Paul Whiteley

Published: March 8, 2024

Published: March 8, 2024

THE CONVERSATION

According to the 2021 census, 6.5% of the population in England and Wales identify as Muslim. In Rochdale, which has just elected George Galloway to be its MP, the proportion of the population identifying as Muslim is far higher – at 30.5%.

As is often the case in byelections, the turnout for the contest that elected Galloway was low. But Galloway received 12,335 votes in a constituency which contains 34,871 Muslims. His campaign focused almost entirely on the war in Gaza rather than local issues, and although we don’t know what proportion of his vote was Muslim, it is a fair assumption that a large percentage of it was.

The question in the wake of Galloway’s election (and one that the new MP is certainly encouraging) is whether this byelection has any implications for Labour in the general election taking place this year?

Keir Starmer has argued that Galloway won because the Labour candidate was sacked after repeating a conspiracy theory that Israel was behind the Hamas attack on October 7 last year. Galloway, by contrast, argues that his victory is a sign that voters are about to turn away from Labour in their droves because they are angry about its failure to call for a ceasefire in Gaza.

Which of them is right?

According to the 2021 census, 6.5% of the population in England and Wales identify as Muslim. In Rochdale, which has just elected George Galloway to be its MP, the proportion of the population identifying as Muslim is far higher – at 30.5%.

As is often the case in byelections, the turnout for the contest that elected Galloway was low. But Galloway received 12,335 votes in a constituency which contains 34,871 Muslims. His campaign focused almost entirely on the war in Gaza rather than local issues, and although we don’t know what proportion of his vote was Muslim, it is a fair assumption that a large percentage of it was.

The question in the wake of Galloway’s election (and one that the new MP is certainly encouraging) is whether this byelection has any implications for Labour in the general election taking place this year?

Keir Starmer has argued that Galloway won because the Labour candidate was sacked after repeating a conspiracy theory that Israel was behind the Hamas attack on October 7 last year. Galloway, by contrast, argues that his victory is a sign that voters are about to turn away from Labour in their droves because they are angry about its failure to call for a ceasefire in Gaza.

Which of them is right?

The Muslim vote

There are 20 constituencies in the UK that have an electorate comprised of more than 30% Muslims. All of them elected a Labour MP in 2019. At the top of the list is Birmingham Hodge Hill, where 62% of the population identifies as Muslim.

In Bradford West 59% of the population is Muslim, in Ilford South, 44%, and in Leicester South, 32%. Rochdale ranks 18th in the list of the 20 constituencies with the largest proportion of Muslim residents. Interestingly enough, just under 19% of the electorate in Holborn and St Pancras, Keir Starmer’s constituency, identifies as Muslim.

There are currently 199 Labour MPs in the House of Commons – a slight reduction from the 202 who were elected in 2019. A bare majority in the House of Commons requires 326 MPs and a working majority more like 346. The party clearly has a mountain to climb to achieve that, even with a lead of around 20% in current polls.

So Starmer will certainly be asking whether Labour can still expect to win seats with a high proportion of Muslim voters in a way that it has done in the past, given what happened in Rochdale. He continues to equivocate over the deaths in Gaza and still follows the government’s line on the conflict, despite it being essentially a colonial war.

Historically, Labour has had a long tradition of anti-colonialism. After the second world war, it was a Labour government that began the process of de-colonisation in the British empire by giving independence to India in 1947.

When is a safe seat not a safe seat?

There is an argument that constituencies with a high proportion of Muslims are relatively safe Labour seats. This is evidenced by the fact that they remained in the Labour camp even when the party suffered a heavy defeat in 2019. The implication is that if anger over Gaza is confined to Muslims, then it is not going to affect the number of seats won by Labour very much.

However, concern about Gaza is shared by people other than Muslims. Polling from YouGov conducted last month shows that there has been a distinct shift in British public opinion about the war since it started. More people are calling for a ceasefire and fewer see Israel’s attacks on Gaza as being justified.

Protesters wearing masks call on Starmer to support a ceasefire. Alamy

Protesters wearing masks call on Starmer to support a ceasefire. AlamyThere is clear evidence that younger voters, in particular, feel more sympathy towards the Palestinian cause than the rest of the population. This is also a group that heavily supported Labour in the 2019 election. While young people in this group are unlikely to switch to voting Conservative over Gaza, the concern for Labour will be that they might abstain in the next election.

How different religions vote

Starmer’s reluctance to call out what is happening in Gaza is a puzzle, since Muslims are overwhelmingly Labour supporters. This can be seen in data from the British Election Study online panel survey conducted after the 2019 general election. The chart shows the relationship between the religious affiliation of the respondents and their voting behaviour in that election.

Religious Affiliation and Voting in the 2019 General Election:

How religious identity maps onto party preference. British Election Study, CC BY-ND

The Church of England used to be described as the “Tory party at prayer” and it clearly remains so today, since 64% of Church of England identifiers supported the Conservatives compared to just 25% who supported Labour.

In contrast, Roman Catholics were marginally more Labour (42%) than Conservative (41%). Nonconformists were similar to Church of England identifiers with 48% Conservative and 25% Labour. Meanwhile, 43% of atheists and agnostics supported Labour and 34% the Conservatives.

Jewish voters favoured the Conservatives by a margin of 56% to 30% Labour. Finally, Muslim voters favoured Labour by a massive 80% compared with the Conservative’s 13%.

If anger over the Gaza war is confined to Muslims it is not likely to influence the outcome of this year’s election. But it is worth remembering that this is not the first time Labour has been damaged by events in the Middle East.

Support for Tony Blair was greatly weakened by his decision to invade Iraq in 2003 at the request of the then US president, George W. Bush. He has never really lived down the reputation he acquired for this mistake.

There is not yet evidence that Labour’s position on Gaza will cost it a majority in the election but the strength of feeling on this issue is growing and the future is not certain. With hundreds of additional seats needed, Starmer can’t afford to take any for granted. The risk of losing these voters to the Conservatives is marginal but the risk of losing them to apathy and disillusionment should have him reconsidering his position.

Author

Paul Whiteley

Paul Whiteley is a Friend of The Conversation.

Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Disclosure statement

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC

Paul Whiteley is a Friend of The Conversation.

Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Disclosure statement

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC

No comments:

Post a Comment