Gowan Dawson on his 3 greatest revelations while writing his book Monkey to Man.

BY GOWAN DAWSON

March 7, 2024

1 The artist who drew the earliest “March of Progress” image disagreed with it

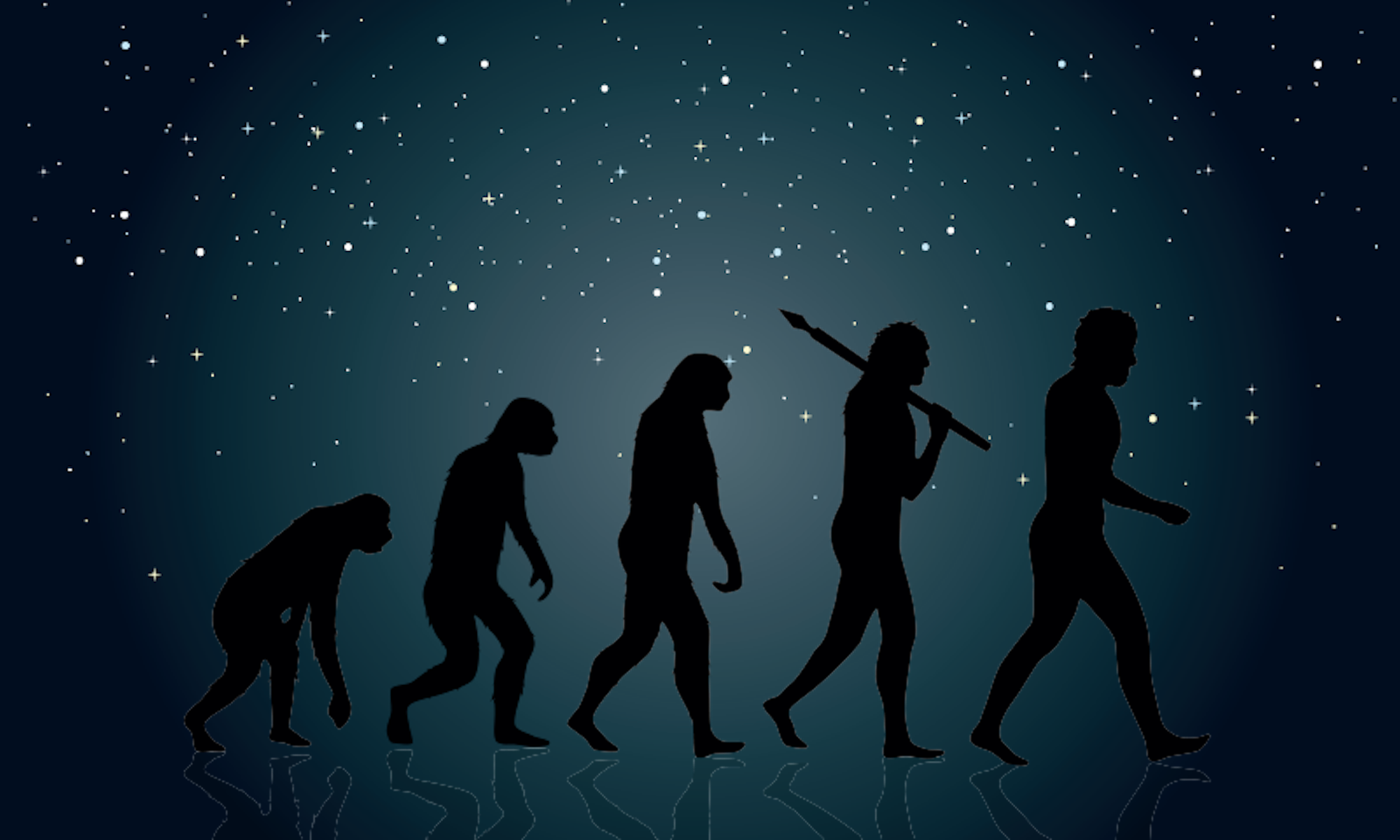

My book, Monkey to Man: The Evolution of the March of Progress Image, tells the story of an iconic image: the “March of Progress,” which depicts evolution as an ascent from apes to humans. Created by scientists and artists in the mid-1960s, the image, originally called “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” still shapes how evolution is understood today

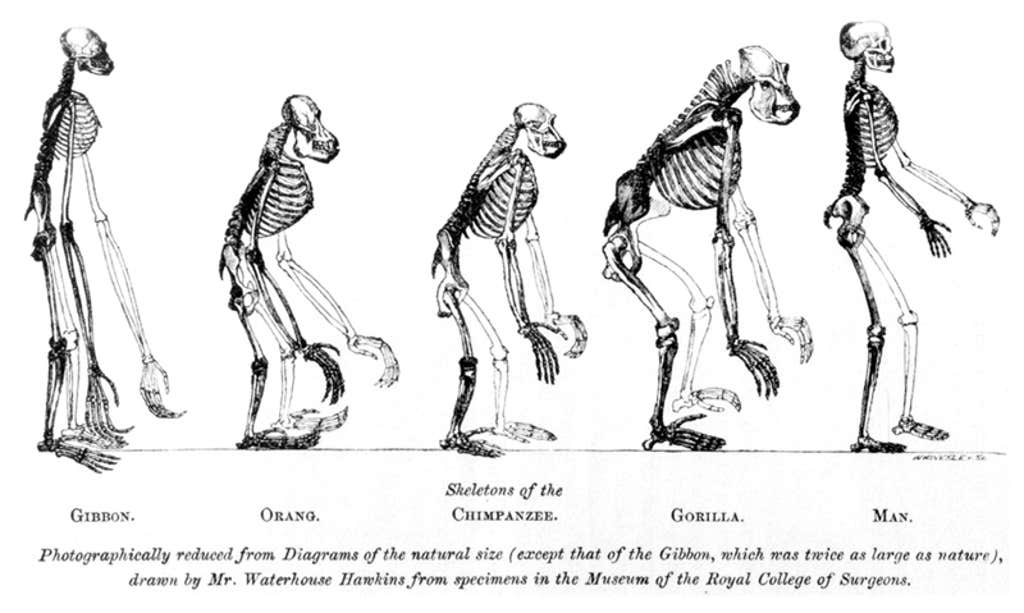

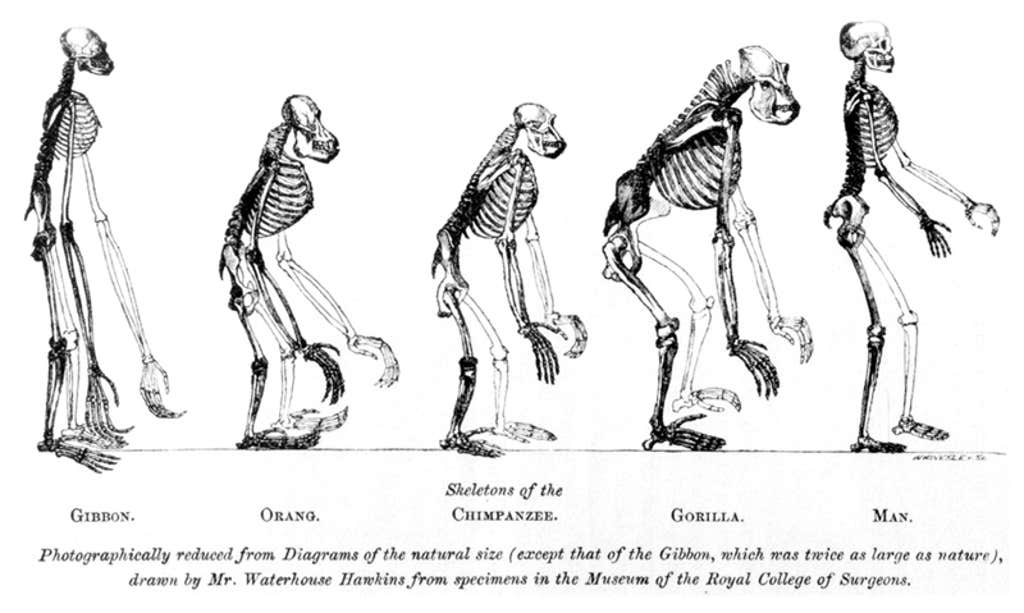

The prototype for that image was the frontispiece for Thomas Henry Huxley’s book Man’s Place in Nature, from 1863. It shows a similar series of primates, from gibbon to gorilla, that become successively taller and more erect, culminating in an upright human. Only here, they appear in skeleton form. What I discovered in the course of my research, from unpublished letters and other sources, was that the artist who drew the skeletons for Huxley’s book, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, was himself bitterly opposed to evolution

My book, Monkey to Man: The Evolution of the March of Progress Image, tells the story of an iconic image: the “March of Progress,” which depicts evolution as an ascent from apes to humans. Created by scientists and artists in the mid-1960s, the image, originally called “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” still shapes how evolution is understood today

The prototype for that image was the frontispiece for Thomas Henry Huxley’s book Man’s Place in Nature, from 1863. It shows a similar series of primates, from gibbon to gorilla, that become successively taller and more erect, culminating in an upright human. Only here, they appear in skeleton form. What I discovered in the course of my research, from unpublished letters and other sources, was that the artist who drew the skeletons for Huxley’s book, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, was himself bitterly opposed to evolution

.

FLAT FOOTED: In this precursor to the march of progress, the artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins embedded an anti-evolutionary message. He drew the gorilla with an unsteady gait to suggest that man did not evolve in a direct line from apes as Darwin and other scientists claimed. Illustration by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, from Huxley, T.H. Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863).

At the time, Darwin’s theory of evolution had only just been introduced: Origin of Species was published in 1859. Huxley was a resolute evolutionist who regarded himself as “Darwin’s bulldog.” Hawkins only agreed to work for him because he needed the money, having two families to support following a bigamous second marriage. As became apparent when they worked together, the two men also disliked each other intensely.

Hawkins nevertheless found ways to surreptitiously introduce his own views into the ascending procession of primate skeletons, particularly in his drawing of the gorilla. This ape totters awkwardly on the sides of its feet, giving the impression that it is more likely to fall over than stride toward humanity. The tottering pose was entirely Hawkins’ creation. The skeleton he drew from, which stood in a museum in London, was placed with its feet flat on the ground, and in anti-evolutionary lectures, Hawkins described gorillas as having “the most waddling gait imaginable.” So this iconic image of evolution actually contains, if you know where to look, clear anti-evolutionary messages.

2 One woman helped keep the controversial “March of Progress” image alive

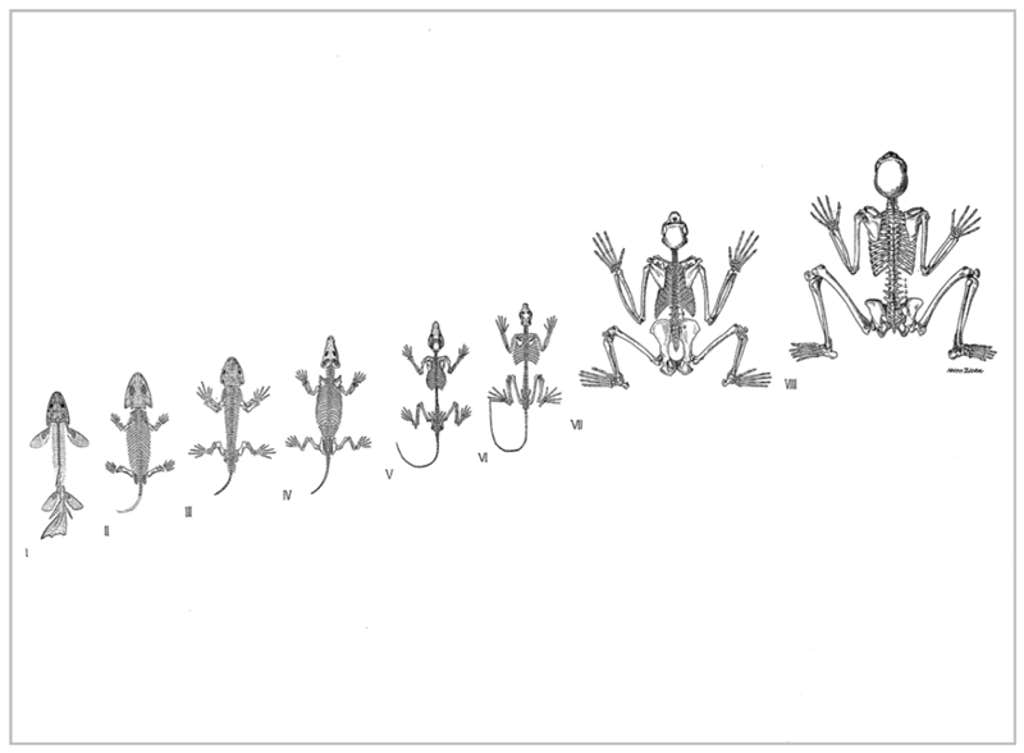

Between the frontispiece to Huxley’s Man’s Place in Nature and “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” depictions of evolution as a gradual ascent from apes to humans were challenged and fell out of favor. In the early 20th century, the iconographic tradition of linear progress was kept alive, pretty much exclusively, by a woman artist who is now almost completely unknown. Even in her own time, Helen Ziska was overworked, poorly paid, and like many female scientific illustrators before and since, not considered a proper artist. Yet without Ziska, the march of progress image—now so famous and consequential—would probably not have come to be.

OUR DEBT: Through her own drawings, little known artist Helen Ziska helped to keep alive the idea of evolution as a linear progression culminating in humans, even when that idea had fallen out of favor. Here Ziska apes “The Road to Homo Sapiens” image, with a series of drawings of vertebrates, titled “Man’s Debt to the Lower Vertebrates.” Illustration by Helen Ziska; from Gregory, W.K. “The Upright Posture of Man,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 67 (1928).

Ziska is a fascinating figure in her own right, and Monkey to Man draws on unpublished letters and original drawings to tell her story for the first time. The daughter of a famous opera singer, Ziska worked at the American Museum of Natural History from the 1920s to the 1940s, and her drawings of evolutionary development, which she made with the primatologist William King Gregory, are imbued with a dark sardonic humor. At times, they also challenge ideas of racial selection, eugenics, and even fascism. When she retired, Ziska had scarcely enough to live on, and spent her final years in penury. It was at precisely this time that her drawings directly inspired the image that would later be published as “The Road to Homo Sapiens.”

3 Scientific enmity left its mark on the “March of Progress” image

It was Elwyn Simons who, as a young man, was inspired by Ziska’s linear drawings of evolutionary ascent, and who subsequently advised the artist Rudolph Zallinger to adopt a similar format for “The Road to Homo Sapiens.” Simons’ integral involvement in the creation of the image was not publicly acknowledged, and only becomes clear through archival materials that were made available following his death in 2016. His covert contribution to the march of progress nevertheless has significant implications. When the illustration was created in the mid-1960s, Simons had already gained a reputation as a brilliant but brash novice, willing to provoke his senior colleagues.

Ziska is a fascinating figure in her own right, and Monkey to Man draws on unpublished letters and original drawings to tell her story for the first time. The daughter of a famous opera singer, Ziska worked at the American Museum of Natural History from the 1920s to the 1940s, and her drawings of evolutionary development, which she made with the primatologist William King Gregory, are imbued with a dark sardonic humor. At times, they also challenge ideas of racial selection, eugenics, and even fascism. When she retired, Ziska had scarcely enough to live on, and spent her final years in penury. It was at precisely this time that her drawings directly inspired the image that would later be published as “The Road to Homo Sapiens.”

3 Scientific enmity left its mark on the “March of Progress” image

It was Elwyn Simons who, as a young man, was inspired by Ziska’s linear drawings of evolutionary ascent, and who subsequently advised the artist Rudolph Zallinger to adopt a similar format for “The Road to Homo Sapiens.” Simons’ integral involvement in the creation of the image was not publicly acknowledged, and only becomes clear through archival materials that were made available following his death in 2016. His covert contribution to the march of progress nevertheless has significant implications. When the illustration was created in the mid-1960s, Simons had already gained a reputation as a brilliant but brash novice, willing to provoke his senior colleagues.

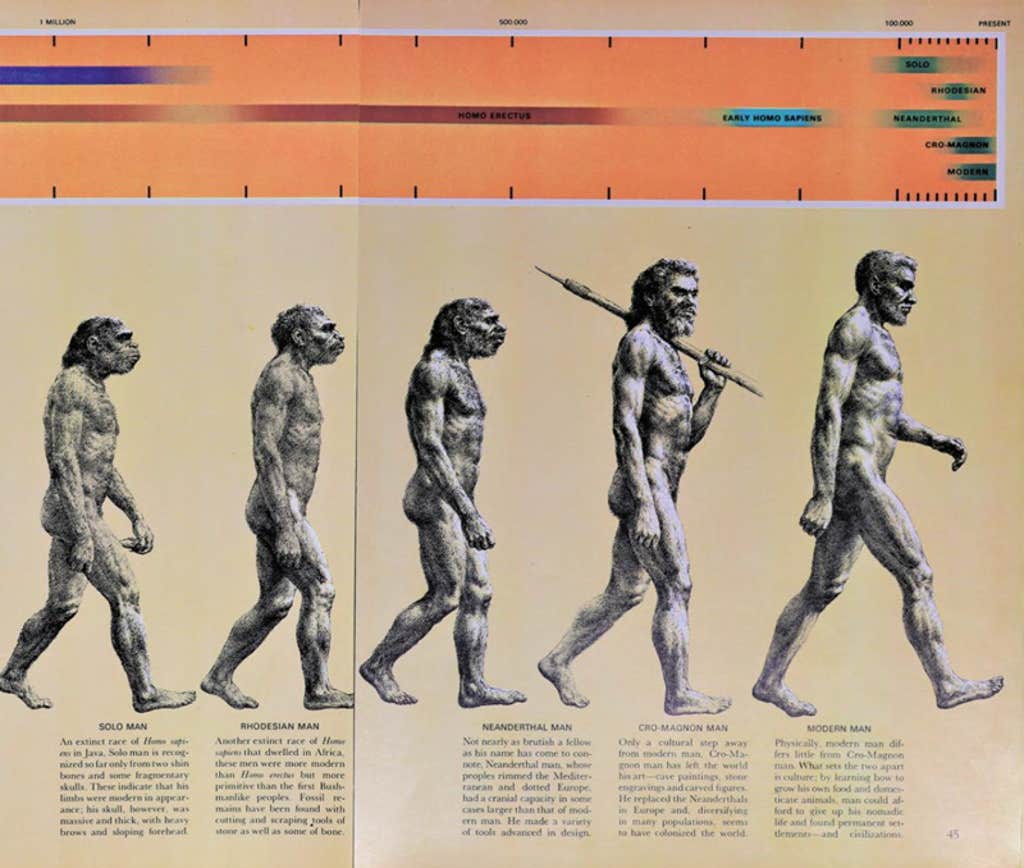

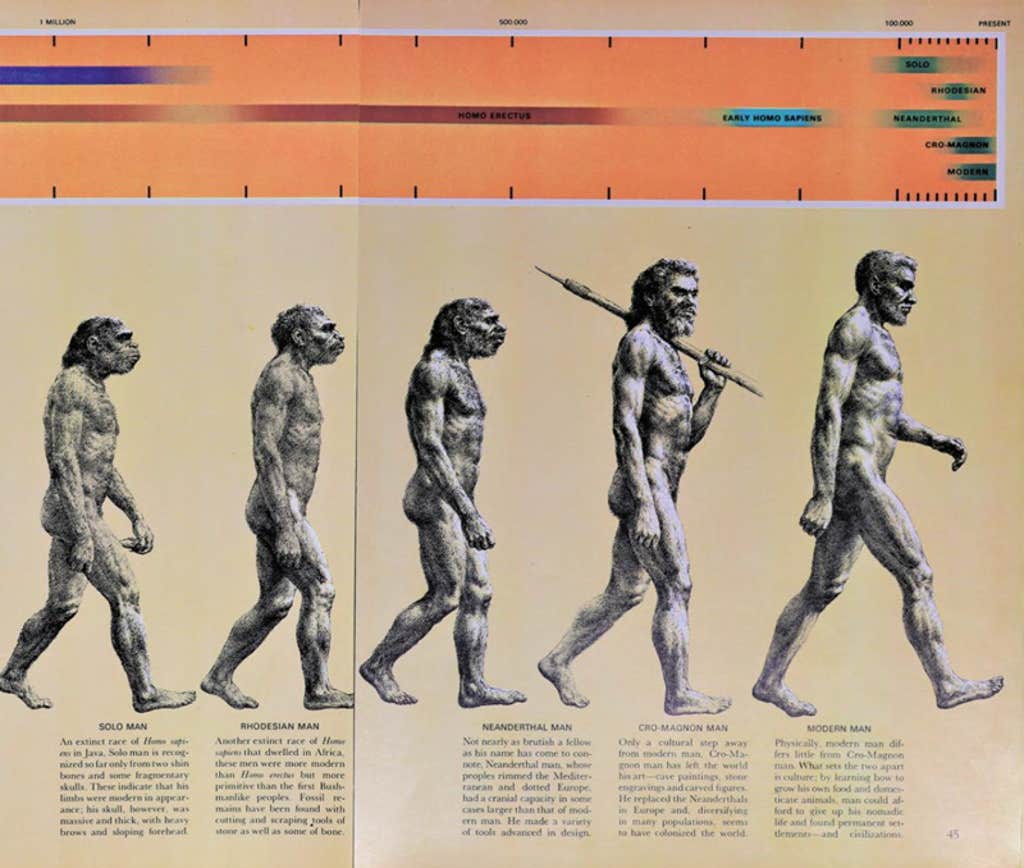

THE LONG ROAD: In its extended form, Rudolph Zallinger’s “The March of Progress” from Time-Life’s 1965 book Early Man, contains 15 figures, instead of the familiar five. Both versions exclude famous fossil hominids discovered and named by celebrated archaeologist Louis Leakey, including Kenyapithecus and Homo habilis. Illustration by Rudolph Zallinger; from “The March of Progress” from Time-Life’s 1965 book Early Man.

In particular, Simons developed a fierce rivalry with one of the most celebrated discoverers of human ancestors, Louis Leakey. Simons’ antagonism toward Leakey informed the scientific advice he gave to Zallinger when he was drawing “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” ensuring that the illustration deliberately omitted the fossil hominids Leakey had discovered and named, including such famous hominid specimens as Kenyapithecus and Homo habilis.

Because Simons’ decisive contribution to the march of progress was not made public, the illustration’s evident anti-Leakey bias was not recognized. Ironically, as the image became increasingly iconic as a representation of human evolution, it was even adopted as the emblem of the foundation set up to further Leakey’s legacy following his death in 1972. The Leakey Foundation is now one of the world’s leading organizations for research into human origins. But the foundation’s logo, which it still continues to use on various digital platforms, was an image that, in its original form, was planned by Leakey’s bitterest rival and which deliberately and systematically excluded his own discoveries.

Posted on March 7, 2024

Gowan Dawson is a professor of Victorian literature and culture at the University of Leicester and an honorary research fellow at the Natural History Museum, London. His work combines the history of science with cultural, literary, and art history. He lives in Leicestershire, U.K.

In particular, Simons developed a fierce rivalry with one of the most celebrated discoverers of human ancestors, Louis Leakey. Simons’ antagonism toward Leakey informed the scientific advice he gave to Zallinger when he was drawing “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” ensuring that the illustration deliberately omitted the fossil hominids Leakey had discovered and named, including such famous hominid specimens as Kenyapithecus and Homo habilis.

Because Simons’ decisive contribution to the march of progress was not made public, the illustration’s evident anti-Leakey bias was not recognized. Ironically, as the image became increasingly iconic as a representation of human evolution, it was even adopted as the emblem of the foundation set up to further Leakey’s legacy following his death in 1972. The Leakey Foundation is now one of the world’s leading organizations for research into human origins. But the foundation’s logo, which it still continues to use on various digital platforms, was an image that, in its original form, was planned by Leakey’s bitterest rival and which deliberately and systematically excluded his own discoveries.

Posted on March 7, 2024

Gowan Dawson is a professor of Victorian literature and culture at the University of Leicester and an honorary research fellow at the Natural History Museum, London. His work combines the history of science with cultural, literary, and art history. He lives in Leicestershire, U.K.

No comments:

Post a Comment