Burial with a horse at the Rákóczifalva site, Hungary (8th century AD). Sándor Hegedűs, Hungarian National Museum

Published: April 24, 2024

How do we understand past societies? For centuries, our main sources of information have been pottery sherds, burial sites and ancient texts.

But the study of ancient DNA is changing what we know about the human past, and what we can know. In a new study, we analysed the genetics of hundreds of people who lived in the Carpathian Basin in southeastern central Europe more than 1,000 years ago, revealing detailed family trees, pictures of a complex society, and stories of change over centuries.

Who were the Avars?

The Avars were a nomadic people originating from eastern central Asia. From the 6th to the 9th century CE, they wielded power over much of eastern central Europe.

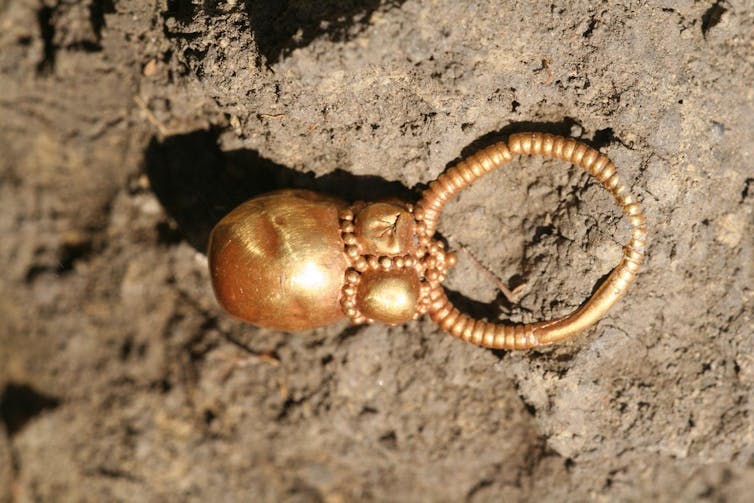

A gold earring from a 7th-century female grave at the Rákóczifalva site, Hungary. Hungarian National Museum, CC BY

The Avars are renowned among archaeologists for their distinctive belt garnitures, but their broader legacy has been overshadowed by predecessors such as the Huns. Nevertheless, Avar burial sites provide invaluable insights into their customs and way of life. To date, archaeologists have excavated more than 100,000 Avar graves.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.Sign up for newsletter

Now, through the lens of “archaeogenetics”, we can delve even deeper into the intricate web of relationships among individuals who lived more than a millennium ago.

Kinship patterns, social practices and population dynamics

Much of what we know about Avar society comes from descriptions written by their enemies, such as the Byzantines and the Franks, so this work represents a significant leap forward in our understanding.

We combined ancient DNA data with archaeological, anthropological and historical context. As a result, we have been able to reconstruct extensive pedigrees, shedding light on kinship patterns, social practices and population dynamics of this enigmatic period.

Excavations at the cemetery of Rákóczifalva, Hungary in 2006. Hungarian National Museum, CC BY

We sampled all available human remains from four fully excavated Avar-era cemeteries, including those at Rákóczifalva and Hajdúnánás in what is now Hungary. This resulted in a meticulous analysis of 424 individuals.

Around 300 of these individuals had close relatives buried in the same cemetery. This allowed us to reconstruct multiple extensive pedigrees spanning up to nine generations and 250 years.

Communities were organised around main fathers’ lines

Our research uncovered a sophisticated social framework. Our results suggest Avar society ran on a strict system of descent through the father’s line (patrilineal descent).

Following marriage, men typically remained within their paternal community, preserving the lineage continuity. In contrast, women played a crucial role in fostering social ties by marrying outside their family’s community. This practice, called female exogamy, underscores the pivotal contribution of women in maintaining social cohesion.

Additionally, our study identified instances where closely related male individuals, such as siblings or a father and son, had offspring with the same female partner. Such couplings are called “levirate unions”.

Read more: In a Stone Age cemetery, DNA reveals a treasured 'founding father' and a legacy of prosperity for his sons

Despite these practices, we found no evidence of pairings between genetically related people. This suggests Avar societies meticulously preserved an ancestral memory.

These findings align with historical and anthropological evidence from societies of the Eurasian steppe.

Our study also revealed a transition in the main line of descent within Rákóczifalva, when one pedigree took over from another. This occurred together with archaeological and dietary shifts likely linked to political changes in the region.

The transition, though significant, cannot be detected from higher-level genetic studies. Our results show an apparent genetic continuity can mask the replacement of entire communities. This insight may have far-reaching implications for future archaeological and genetic research.

Future direction of research

Our study, carried out with researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, is part of a larger project called HistoGenes funded by the European Research Council.

This project shows we can use ancient DNA to examine entire communities, rather than just individuals. We think there is a lot more we can learn.

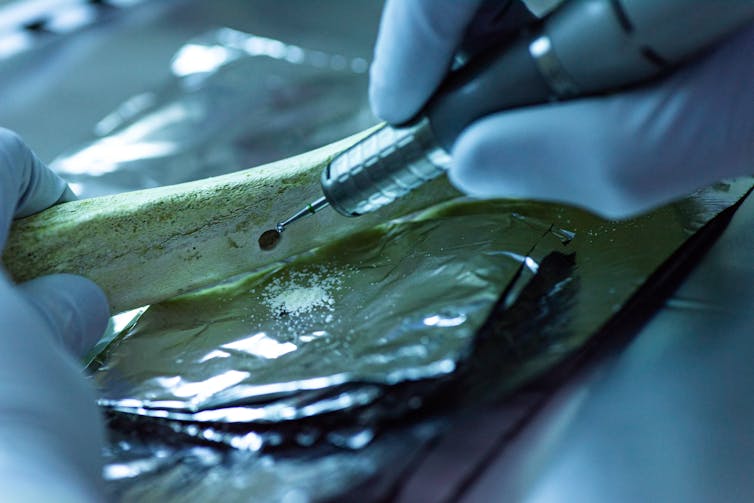

An expert at work harvesting ancient DNA from a human bone. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Now we aim to deepen our understanding of ancestral Avar society by expanding our research over a wider geographical area within the Avar realm. This broader scope will allow us to investigate the origins of the women who married into the communities we have studied. We hope it will also illuminate the connections between communities in greater detail.

Additionally, we plan to study evidence of pathogens and disease among the individuals in this research, to understand more about their health and lives.

Read more: Ancient DNA reveals children with Down syndrome in past societies. What can their burials tell us about their lives?

Another avenue of research is improving the dating of Avar sites. We are currently analysing multiple radiocarbon dates from individual burials to reveal a more precise timeline of Avar society. This detailed chronology will help us pinpoint significant cultural changes and interactions with neighbouring societies.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions to this work of Zsófia Rácz, Tivadar Vida, Johannes Krause and Zuzana Hofmanová.

Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Archaeogenetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Disclosure statement

Magdalena M.E. Bunbury receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) (project number CE170100015). She currently carries out a cadetship at the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre, a non-profit organisation in Cairns. Previously, she received funding from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) (project number D0850554) and the Erasmus scheme of the European Union.

Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone receives funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 856453.

The story of the first Alor people adapting to climate change 43,000 years ago

As humans, our greatest evolutionary advantage has always been our ability to adapt and innovate. When people first reached the expanded coastline of Southeast Asia around 65,000 years ago, and faced the sea crossings necessary to continue east into the islands of the Wallacean archipelago (the migration of Homo sapiens out of Africa to Australia), these abilities were put to use like never before.

Our study reports new evidence that humans reached and settled on the island of Alor, East Nusa Tenggara, around 43,000 years ago.

Alor is a smaller island lying between the larger islands of Flores and Timor, on the southern migratory pathway between mainland Southeast Asia and Australia.

Traces of settlements from that time demonstrate that once people began to move into the islands, they did so very quickly, and rapidly adjusted to their new island homes, especially in terms of acquiring food.

Life traces in Makpan Cave

Our collaborative research project, involving Australian and Indonesian archaeologists, excavated Makpan cave on Alor's south-west coast in mid-2016.

We identified the presence of human occupants in Makpan cave by discovering various tools made from stone, shell, and coral, as well as the remains of marine shell and sea urchins, for which humans are the only likely transport agents from coast to cave.

We used radiocarbon dating of preserved charcoal and marine shell to determine the period of human occupation at Makpan. The presence of both these materials in the cave is a direct result of human activity, so their dates can be directly connected to when people were living at Makpan.

The Makpan dates push back the record for human occupation on Alor island, doubling the initial occupation date of 21,000 years previously recovered from Tron Bon Lei, excavated in 2014.

This new find shows that Alor was occupied at the same time as Flores to the west, and Timor to the east—confirming Alor's position as a 'stepping-stone' between these two larger islands.

The deepest levels of the Makpan deposit recovered evidence for human occupation (such as stone tools and food waste) but in very low numbers. This suggests that when people first arrived at Makpan, they did so in low numbers.

During the 43,000 years of human occupation, Makpan witnessed a series of significant rises and falls in sea levels. This was caused by extreme climate changes during the last ice age. These environmental changes led the inhabitants of Makpan cave to undergo several phases of adaptation to environmental changes.

1. Early habitation phase

During the period from 43,000 to 14,000 years ago, when sea levels were lower, the inhabitants of Makpan relied more on coastal resources as they were more easily accessible.

During the Late Pleistocene (ice age), the lower sea level meant Alor Island was still connected to Pantar Island to the west. This created a mega-island that was nearly twice its size.

This condition eliminated the Pantar Strait between Pantar and Alor. The Pantar Strait is a passage for strong ocean currents connecting the Flores and Savu seas. Instead, the strait was replaced by a large sheltered bay.

Falling sea levels as the last ice age reached its maximum extent, also increased the distance from the site of Makpan to the coast.

This increased distance likely encouraged people to broaden their diet away from an intensely marine focus, to include a variety of land-based fruits and vegetables and perhaps make more use of giant rats, which were the only terrestrial fauna of any size available on the island at this time. This scenario is supported by isotopic analysis of human teeth from Makpan.

2. Pleistocene-Holocene transition phase

As the ice age began to wane around 14,000 years ago (the transition period from the Pleistocene to the early Holocene), bringing Makpan back within less than 1km of the coast, we see evidence for increased use of marine resources and foraging in the sheltered bay region, rocky coastline, reefs and deeper waters off Alor's south coast.

This increased access to a variety of marine protein sources is represented by the veritable smorgasbord of seafoods forming the dense midden deposits between around 12,000–11,000 years ago.

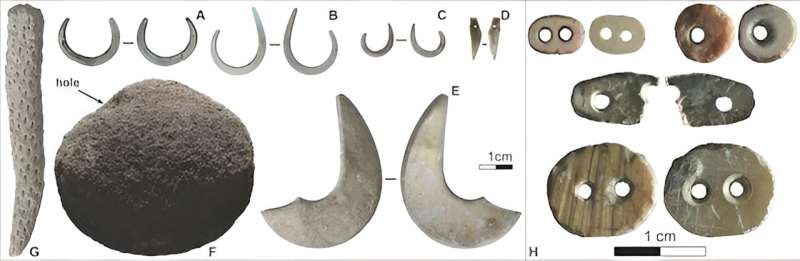

It is no surprise that the site sees significant evidence for fishing at this time, not just the bones of a wide variety of fish and shark species, but also in the form of shell fishhooks in different shapes and sizes. It also has the other items needed for fishing such as sinkers, and files made of coral used to make the hooks. The hooks were made from highly nacreous (i.e., shiny) shell species—which may have assisted in attracting the fish.

Although we do not find perishable organic materials, the diversity of fish hook types found in Makpan implies the use of fiber lines and nets, and the ability to fish in both shallow and deep water.

3. Late habitation phase

As sea levels continued to rise in the Early-Middle Holocene, the Pantar Strait opened up once more and we see the loss of the sheltered bay resources from the Makpan diet alongside an increase in reliance on terrestrial foods.

This coincided with a decline in occupation intensity, culminating in the abandonment of Makpan about 7,000 years ago. Why Makpan was abandoned at this time we do not know. Perhaps these final sea level increases made other areas around Alor island more attractive settlement locations, encouraging people to relocate.

The cave was reoccupied in the Neolithic (about 3,500 years ago), after sea-levels had stabilized, and we see a significant change in technology and lifestyle—evidenced by the appearance of pottery and domestic animals in the deposits. The Makpan archaeological record shows just how inventive and adaptive modern humans were in response to global climate change.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]() 40,000 years of adapting to sea-level change on Alor Island

40,000 years of adapting to sea-level change on Alor Island

No comments:

Post a Comment