Titled “Nazism and the Journal,” the article is part of a series written by independent historians that focuses on biases and injustices that New England Journal of Medicine has historically countenanced

By JACKIE HAJDENBERG (JTA)April 4, 2024,

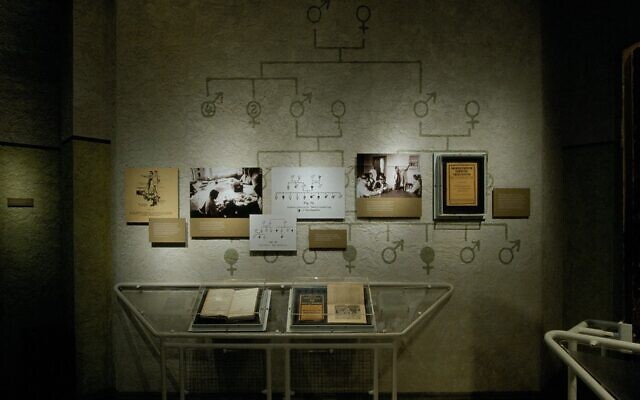

A special exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race," explores how the Nazis developed racial health policies that began with the mass sterilization of individuals considered to be "biological threats." (Courtesy United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

A leading American medical journal praised the Nazi Party’s medical practices in the 1930s and was slow to acknowledge Nazi Germany’s antisemitic abuse, according to a historical retrospective the journal is publishing this week.

The article, which has been published online and will appear in the Thursday print edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, addresses the publication’s history of endorsing Nazi race science.

“We hope it will enable us to learn from our mistakes and prevent new ones,” write authors Joelle M. Abi-Rached and Allan M. Brandt, both historians of medicine affiliated with Harvard University.

Titled “Nazism and the Journal,” the article is part of a series written by independent historians that focuses on biases and injustices that NEJM has historically countenanced. Previous entries have addressed eugenics and racism in medicine as well as diversity in medical residency programs.

The article concludes that the journal “paid only superficial and idiosyncratic attention to the rise of the Nazi state” until the end of World War II, even as competitors dealt forthrightly with the health implications of the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews.

According to the article, NEJM first mentioned Adolf Hitler in a 1935 article by Michael M. Davis, a leading figure in American health policy, and Gertrud Kroeger, a preeminent German nurse who was later revealed to be a Nazi sympathiser. In that article, the two praised the reorganisation of national health insurance in Nazi Germany uncritically and in a detached manner, Abi-Rached and Brandt write.

By that time, Jews were already banned from a range of prestigious jobs, including at public universities, and Jewish doctors faced restrictions on their ability to practice medicine.

“There is no reference to the slew of persecutory and antisemitic laws that had been passed after the Nazis assumed power in January 1933,” Abi-Rached and Brandt write. “Davis and Kroeger sympathetically described the requirement that insurance physicians complete 3 months of compulsory service at newly established labor camps in rural areas.”

Abi-Rached and Brandt also found that the Journal “enthusiastically praised German forced sterilisation and the restrictive alcohol policies of the Hitler Youth.” A 1934 article about sterilization, titled “Sterilization and Its Possible Accomplishments” is still available in the journal’s online archive.

The Third Reich had enacted the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseasesin 1933, requiring the forced sterilisation of people with certain mental and physical disabilities. By 1935, the Marital Health Law banned marriages between those deemed “hereditarily healthy” and those who were not — the same year Nazi Germany stripped Jews of citizenship and prohibited them from marrying non-Jews.

The medical journal did not acknowledge Nazi war crimes until 1944, with the publication of an editorial titled “Epidemic Starvation” about the dire conditions in concentration camps in Eastern Europe.

“Mass starvation has rarely, if ever, been distributed so ruthlessly or so systematically to civilian populations as has been the case in occupied Europe in the present struggle,” the authors wrote in the 1944 article.

By contrast, Abi-Rached and Brandt found that a competing publication, the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, “frequently informed its readership about the detrimental impact of Nazi rule on medical practice,” including by “detailing the persecution of Jewish physicians, including the restriction of their practice and access to medical education.”

NEJM only issued one “explicitly critical piece” in 1933 titled “The Abuse of the Jewish Physicians,” which was a short notice appended to an article about a surgical treatment for tuberculosis.

Abi-Rached and Brandt note that Davis and Kroeger’s article was challenged by a letter to the editor which, they said, “showed sympathy for the Jewish doctors.” (They also note that despite praising Nazi practices, Davis himself had Jewish ancestry.) But the letter in question primarily focused on the threat of socialized medicine. Other articles published in NEJM at the time, they noted, were “overwhelmingly about the compulsory and oversubscribed sickness insurance system, ‘socialised medicine,’ and ‘quackery,’ not the persecution and mass extermination of Jews.”

The publication’s first overt condemnation of the Nazis’ medical abuses did not appear until 1949 after Leo Alexander, a Viennese-born American Jewish psychiatrist and neurologist, compiled evidence to use against Nazi doctors at the Nuremberg trials. Alexander also wrote part of the Nuremberg Code, which provides legal and ethical guidance for scientific experimentation on humans following revelations about Nazi experiments on Jews.

In the 1960s and onward, the New England Journal of Medicine published additional articles documenting the medical atrocities committed by the Nazi medical establishment, as ethical standards became increasingly widespread.

Reflecting on the journal’s omissions during the Holocaust, Abi-Rached and Brandt grasp for explanations and arrive at ones that they say have implications for contemporary scholarship about medicine.

“Part of the answer lies in denial, compartmentalisation, and rationalisation, all of which depend on structural and institutional racism — deep historical, often unrecognised, bias and discrimination that serve the status quo,” they write.

No comments:

Post a Comment