An overdue ruling from the Oversight Board.

By RUSSELL BRANDOM

This article originally appeared in Exporter, a weekly newsletter covering the latest on U.S. tech giants and their impact outside the West, with Russell Brandom.

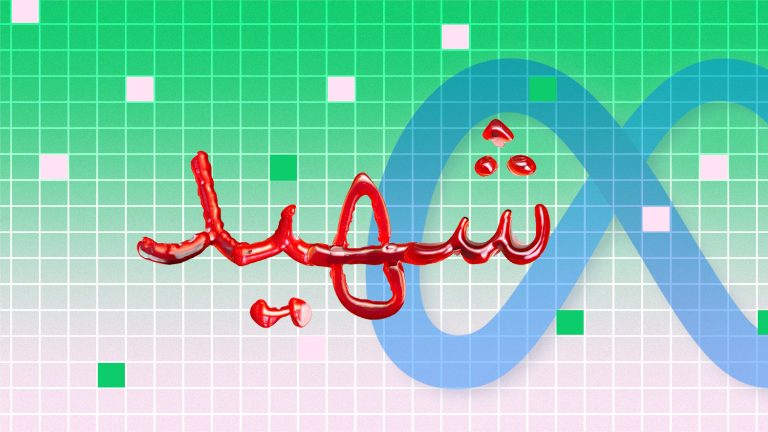

On Tuesday, the Meta-established Oversight Board released a new ruling on how Facebook moderates the Arabic word “shaheed,” which translates roughly to “martyr.” Meta had been automatically flagging the word when applied to a person on its Dangerous Organizations and Individuals list, taking it as an inherent call to violence. When the Oversight Board case re-examining the policy was announced, “shaheed” was responsible for more content removals than any other single word or phrase.

This week’s ruling found that Meta’s policy “disproportionately restricts freedom of expression and civic discourse” — which is a long way of saying it was taking down too much content that shouldn’t have been taken down. As it tried to stop users from glorifying terrorists, the company had instead made the entire topic of political violence off-limits to Arabic speakers.

Marwa Fatafta, who directs Middle East policy at Access Now, told me Meta’s treatment of “shaheed” is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how the word is used. “It’s a word that comes from Islam, but it’s used by Arabic speakers regardless of religion,” Fatafta says. “At least in the Palestine context, you refer to anyone killed by the Israeli army as ‘shaheed’ — or anyone killed in an act of political violence.”

That could include people like Shireen Abu Akleh, the Al Jazeera reporter killed by Israeli soldiers in 2022, but it could also include Egyptian protestors killed in Tahrir Square. Given the ongoing horror in Palestine, it would be difficult to talk about any of the victims without using some version of the word.

It’s tempting to read the decision as a response to the violence in Palestine, but the opposite is true: The board announced it was tackling the case last March, and delayed the decision in the wake of the October 7 attacks. Meta had launched its review of how the word was being moderated in 2020, but the review concluded without reaching a consensus. Without some kind of outside nudge, there simply wasn’t enough political will within the company to change the rule.

Part of the problem here is a simple language issue. Overreading the meaning of an Arabic word is easier when there are fewer native speakers of the language at high levels of the company. Even after the issue was raised, it lingered unresolved — perhaps because the company’s leadership didn’t see it as a priority. Such language bias is pervasive in the tech industry, where global tools are still mostly made by English speakers, and this is a prime example.

But the problem doesn’t end there. Fatafta described the policy as “a stigmatization of Arabic populations,” and it’s hard to disagree. Throughout the West, there’s a sad tendency to see Arabic speakers as only the perpetrators of political violence, never the victims. In Meta’s case, that tendency ended up being written into moderation policy and operationalized at a massive scale. It’s the kind of de jure discrimination that the Oversight Board was founded to address. The greatest frustration is that Meta couldn’t solve this problem on its own.

Russell Brandom is the U.S. Tech Editor at Rest of World.

No comments:

Post a Comment