What Are China's Ambitions in the Antarctic?

[By Benjamin Sacks and Peter Dortmans]

The recent opening of China’s Qinling base, its third permanent Antarctic station, has worried some Australian and American observers. Their concerns suggest it may be time for Australia to delineate China’s Antarctic ambitions more clearly and better organise its response.

Qinling is China’s first base located adjacent to the Ross Sea, south of Australia and New Zealand and near the US McMurdo base. Its satellite monitoring facility has raised Western apprehensions. Qinling could become another node in China’s People’s Liberation Army-affiliated BeiDou navigation network and be used to monitor Australian and New Zealand communications.

Some of Beijing’s own statements have supported these concerns, with China’s National Defense University’s Science of Military Strategy (2020) stating that “the polar regions have become an important direction for our country’s interests to expand overseas and far frontiers, and it has also proposed new issues and tasks for the use of our country’s military power”. Elizabeth Buchanan notes that the Chinese government’s civil-military fusion law requires “all civilian research activities…to have military application or utility for China. This extends to China’s Antarctic footprint”.

While experts should be concerned, they might be worried for the wrong reasons. Claire Young has stressed that Antarctica’s sheer remoteness and extreme climate limit its potential for Chinese military activities, at least with existing technology. She argues that Qinling is simply too distant from Australia and New Zealand to effectively monitor their communications. China could more easily monitor from neighbouring states or its disputed South China Sea artificial islands.

A 2023 RAND study, while acknowledging the potential military risks posed by China’s Antarctic activities, added that Chinese officials have affirmed their respect for the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and subsequent protocols, collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System. The Madrid Protocol, for instance, banned Antarctic mining. China is a signatory.

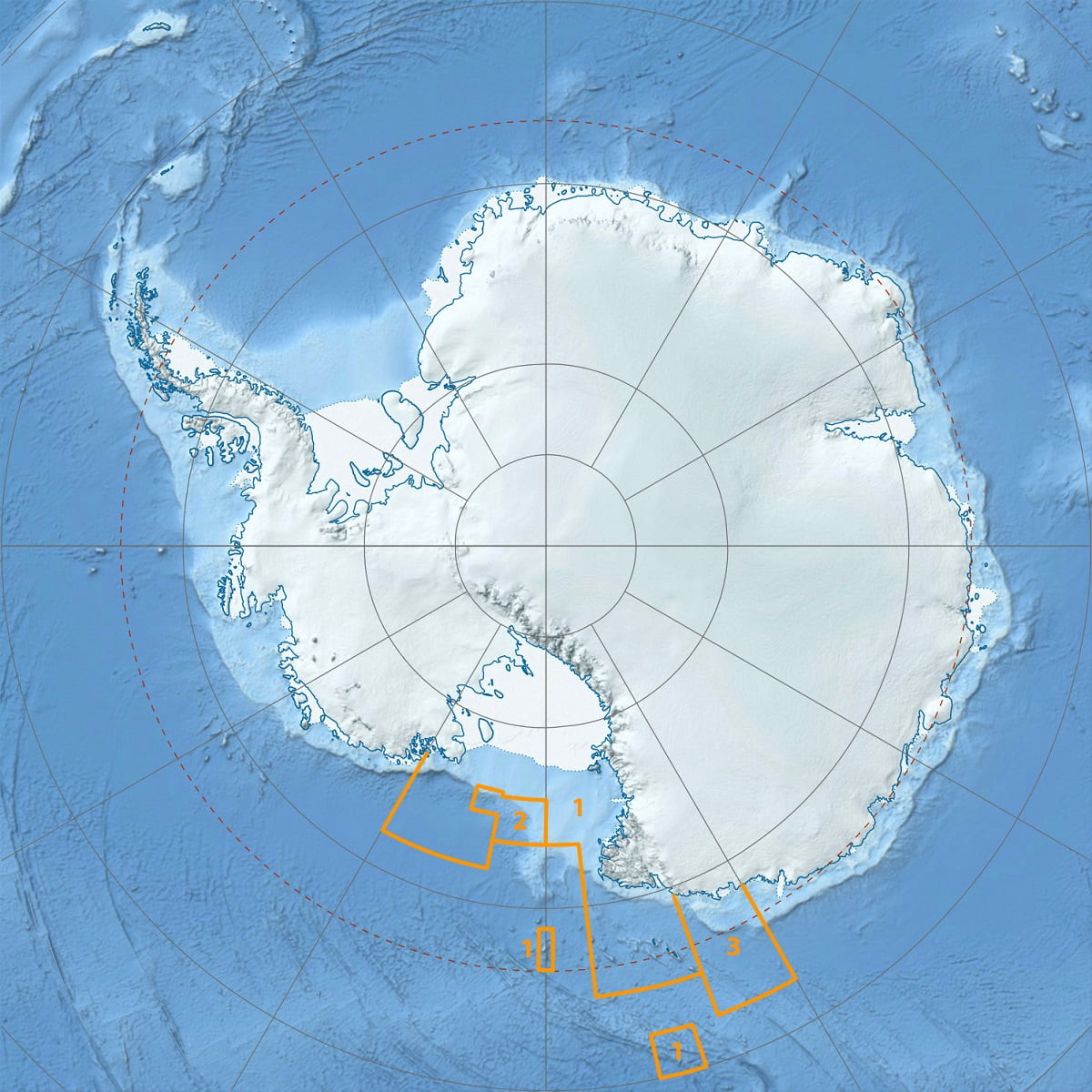

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area includes a (1) General Protection Zone; (2) Special Research Zone; and (3) Krill Research Zone (Wikimedia Commons)

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area includes a (1) General Protection Zone; (2) Special Research Zone; and (3) Krill Research Zone (Wikimedia Commons)

What, then, are China’s long-term ambitions? Buchanan has argued that, in the Antarctic semi-regulated global commons, “presence equals power”. RAND, through an examination of both English- and Chinese-language sources, concluded that Beijing seeks a “right to speak” in Antarctic regional affairs and that this could be part of China’s efforts to shift the balance of Antarctic influence in its favour ahead of any future Antarctic Territory renegotiation.

These efforts appear to be driven primarily by economics, especially in regard to krill fishing and mining, both of which fall under China’s vague goal of Antarctic “utilisation”. Along with Russia, China’s long-distance fishing fleet – the world’s largest – is rapidly expanding its krill industry, deploying super trawlers in the name of scientific research (in krill research zones) that will eventually collect more krill than is allowed under the Antarctic Territory System.

Both Russia and China have repeatedly rejected new marine protection areas and are likely to continue growing their lucrative fishing industries. China has so far resisted other signatories’ efforts to rein in its fishing ambitions. While other signatories are willing to abide by the limits imposed by the Antarctic Territory System, China and Russia appear to want to ignore them.

Similarly, China is eager to undertake onshore and offshore mineral extraction in Antarctica, despite being a signatory to the 1991 Madrid Protocol, which bans such activities. Some experts posit that in the future, China may be able to develop advanced mining technologies in anticipation of the Protocol’s potential 2048 renegotiation where it may seek to legalise some forms of mining. As the Antarctic Territory System currently has no enforcement mechanism, RAND added that Chinese Antarctic mining activities could consequently open “the floodgates for similar activities”.

Given that any signatory can call for the Antarctic Treaty’s renegotiation at any time – a privilege China has yet to invoke – it appears Beijing is biding its time while diversifying its Antarctic presence. Under this reasoning, China’s recent actions, including the opening of Qinling base, constitute long-term shaping activities to place itself in the strongest position possible ahead of any changes to the Treaty.

How should Australia and its allies and partners respond? Some observers have highlighted the Antarctic Territory System’s provision for unannounced inspections as key to mitigating Chinese ambitions. However, Russia has demonstrated that it can block inspections by making “station runways inaccessible” and switching off station radios “to block parties landing”.

Nengye Liu has suggested that Australia update its 2009 Australia–China Joint Statement to explicitly ensure the peaceful stability of bilateral Antarctic relations, given China’s significant Australian Antarctic Territory presence. Australia and its allies and partners should publicly “name-and-shame” China’s activities when and if they violate the Antarctic Territory System. Australia should consider sanctions against relevant Chinese individuals, state-owned enterprises, and the Polar Research Institute of China.

Given the uncertainties of Antarctica’s geopolitical future, as evidenced by growing concerns over China’s regional activities and ambitions, it may be time for the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to establish its own Antarctic Affairs office. Such an office could be charged with establishing Australia’s future strategy and contingencies, working across government to implement its official position, and negotiating and building an international consensus with allies and partners.

Dr Benjamin J. Sacks is a policy researcher at RAND and a professor of political geography at the RAND Pardee Graduate School.

Dr Peter Dortmans is a Senior Researcher at RAND Australia, working primarily in strategic, technology and policy issues for the Defence and National Security community.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment