Susanne Rust

Thu, May 16, 2024

As researchers increasingly rely on wastewater testing to monitor the spread of bird flu, some are questioning the reliability of the tests being used. Above, the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Playa Del Rey. (Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

As health officials turn increasingly toward wastewater testing as a means of tracking the spread of H5N1 bird flu among U.S. dairy herds, some researchers are raising questions about the effectiveness of the sewage assays.

Although the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says current testing is standardized and will detect bird flu, some researchers voiced skepticism.

"Right now we are using these sort of broad tests" to test for influenza A viruses in wastewater, said epidemiologist Denis Nash, referring to a category of viruses that includes normal human flu and the bird flu that is circulating in dairy cattle, wild birds, and domestic poultry.

"It's possible there are some locations around the country where the primers being used in these tests ... might not work for H5N1," said Nash, distinguished professor of epidemiology and executive director of City University of New York’s Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health.

Read more: What you need to know about the bird flu outbreak, concerns about raw milk, and more

The reason for this is that the tests most commonly used — polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests — are designed to detect genetic material from a specific organism, such as a flu virus.

But in order for them to identify the virus, they must be "primed" to know what they are looking for. Depending on what part of the virus researchers are looking for, they may not identify the bird flu subtype.

There are two common human influenza A viruses: H1N1 and H3N2. The "H" stands for hemagglutinin, which is an identifiable protein in the virus. The "N" stands for neuraminidase.

The bird flu, on the other hand, is also an influenza A virus. But it has the subtype H5N1.

That means that while the human and avian flu virus share the N1 signal, they don't share an H.

If a test is designed to look for only the H1 and H3 as indicators of influenza A virus, they're going to miss the bird flu.

Marc Johnson, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri, said he doesn't think that's too likely. He said the generic panels that most labs use will capture H1, H3 and H5.

He said while his lab specifically looks for H1 and H3, "I think we may be the only ones doing that."

It's been just in the last few years that health officials have started using wastewater as a sentinel for community health.

Alexandria Boehm, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University and principal investigator and program director for WastewaterSCAN, said wastewater surveillance really got going during the pandemic. It's become a routine way to look for hundreds if not thousands of viruses and other pathogens in municipal wastewater.

"Three years or four years ago, no one was doing it," said Boehm, who collaborates with a network of researchers at labs at Stanford, Emory University and Alphabet Inc.’s life sciences research organization. "It sort of evolved in response to the pandemic and has continued to evolve."

Since late March, when the bird flu was first reported in Texas dairy cattle, researchers and public health officials have been combing through wastewater samples. Most are using the influenza A tests they had already built into their systems — most of which were designed to detect human flu viruses, not bird flu.

Read more: Flu season is over, but there is a viral surge in California wastewater. Is it avian flu?

On Tuesday, the CDC released its own dashboard showing wastewater sites where it has detected influenza A in the last two weeks.

Displaying a network of more than 650 sites across the nation, there were only three sites — in Florida, Illinois and Kansas — where levels of influenza A were considered high enough to warrant further agency investigation. There were more than 400 where data were insufficient to allow a determination.

Jonathan Yoder, deputy director of the CDC's Division of Infectious Disease Readiness and Innovation, said those sites were deemed to have insufficient data because testing hasn't been in place long enough, or there may not have been enough positive influenza A samples to include.

Asked if some of the tests being used could miss bird flu because of the way they were designed, he said: "We don't have any evidence of that. It does seem like we're at at a broad enough level that we don't have any evidence that we would not pick up H5."

He also said the tests were standardized across the network.

"I'm pretty sure that it's the same assay being used at all the sites," he said. "They're all based on ... what the CDC has published as a clinical assay for for influenza A, so it's based on clinical tests."

But there are discrepancies between the CDC's findings and others'.

Earlier this week, a team of scientists from Baylor College of Medicine, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, the Texas Epidemic Health Institute and the El Paso Water Utility, published a report showing high levels of bird flu from wastewater in nine Texas cities. Their data show that H5N1 is the dominant form of influenza A swirling in these Texas towns' wastewater.

But unlike other research teams, including the CDC, they used an "agnostic" approach known as hybrid-capture sequencing.

"So it's not just targeting one virus or one of several viruses," as one does with PCR testing, said Eric Boerwinkle, dean of the UTHealth Houston School of Public Health and a member of the Texas team. "We're actually in a very complex mixture, which is wastewater, pulling down viruses and sequencing them."

"What's critical here is it's very specific to H5N1," he said, noting they'd been doing this kind of testing for approximately two years, and hadn't ever seen H5N1 before the middle of March.

Blake Hanson, an assistant professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health and a member of the Texas wastewater team, agreed, saying that PCR-based methods are "exquisite" and "highly accurate."

"But we have the ability to look at the representation of the entire genome, not just a marker component of it. And so that has allowed us to look at H5N1, differentiate it from some of our seasonal fluids like H1N1 and H3N2," he said. "It's what gave us high confidence that it is entirely H5N1, whereas the other papers are using a part of the H5 gene as a marker for H5."

Boerwinkle and Hanson underscored that while they could identify H5N1 in the wastewater, they cannot tell where it came from.

"Texas is really a confluence of a couple of different flyways for migratory birds, and Texas is also an agricultural state, despite having quite large cities," Boerwinkle said. "It's probably correct that if you had to put your dime and gamble what was happening, it's probably coming from not just one source but from multiple sources. We have no reason to think that one source is more likely any one of those things."

But they are pretty confident it's not coming from people.

"Because we are looking at the entirety of the genome, when we look at the single human H5N1 case, the genomic sequence ... has a hallmark amino acid change ... compared to all of the cattle from that same time point," Hanson said. "We do not see that hallmark amino acid present in any of our sequencing data. And we've looked very carefully for that, which gives us some confidence that we're not seeing human-human transmission."

The Texas' team approach was really exciting, said Devabhaktuni Srikrishna, the CEO and founder of PatientKnowHow.com, noting it exhibited "proof of principle" for employing this kind of metagenomic testing protocol for wastewater and air.

He said government agencies, private companies and academics have been searching for a reliable way to test for thousands of microscopic organisms — such as pathogens — quickly, reliably and at low cost.

"They showed it can be done," he said.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

CDC makes public influenza A wastewater data to assist bird flu probe

Reuters

Tue, May 14, 2024 at 9:38 AM MDT·2 min read

FILE PHOTO: Illustration shows test tubes labelled "Bird Flu" and U.S. flag

(Reuters) - The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on Tuesday released data on influenza A found in wastewater in a public dashboard that could assist in tracking the outbreak of H5N1 bird flu that has infected cattle herds.

Last week, an agency official told Reuters about U.S plans to make public data collected by its surveillance system.

While the threat from the virus to people has been classified as low at this time, scientists are closely watching for changes in the virus that could make it spread more easily among humans.

Testing wastewater from sewers proved to be a powerful tool for detecting mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 virus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the week ended May 4, the agency's surveillance system did not show any indicators of unusual influenza activity in people, including the H5N1 virus. The virus has been detected among dairy cattle in nine U.S. states since late March.

The testing did detect unusually high levels of influenza A in Saline County, Kansas. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has confirmed four herds tested positive in Kansas, the last on April 17. Neither Kansas nor USDA have posted the counties where the herds were located.

CDC said that it is actively looking at multiple flu indicators to monitor for influenza A, of which H5N1 is a subtype, including looking for signs of spread of the virus to, or among, people, in areas where it has been identified.

For monitoring influenza A virus in wastewater, CDC compares the most recent weeks of influenza A virus levels recorded at a wastewater site to levels reported between Oct. 1, 2023 and March 2, 2024 for that same wastewater site. Those at or above the 80th percentile are categorized as high.

However, the testing cannot identify the source of the virus or whether it came from an infected bird, human or milk.

"By tracking the percentage of specimens tested that are positive for influenza A viruses, we can monitor for unusual increases in influenza activity that may be an early sign of spread of novel influenza A viruses, including H5N1," the CDC said in its report.

The public database will allow individuals to check for increases in influenza A cases in their area, or spot any unusual flu activity.

(Reporting by Bhanvi Satija in Bengaluru; Additional reporting by Julie Steenhuysen and Tom Polansek in Chicago; Editing by Bill Berkrot)

CDC launches new dashboard to track bird flu outbreak in your area

James Liddell

Wed, May 15, 2024

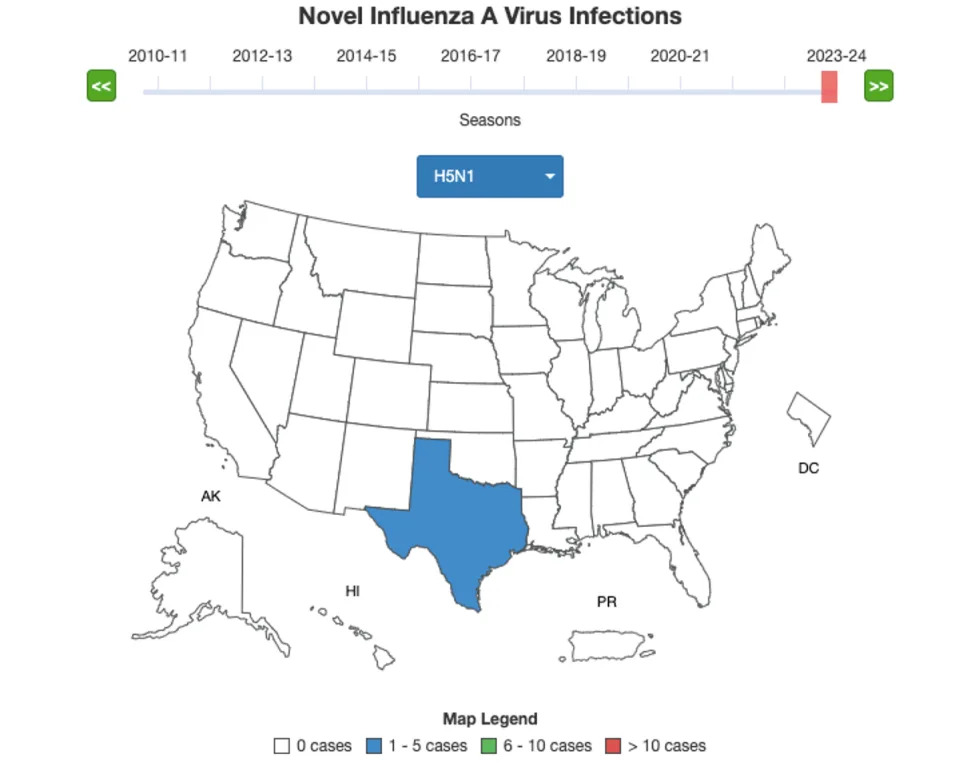

Dashboard maps US bird flu cases (CDC)

A new dashboard to monitor the spread of bird flu has been released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as rates rise among dairy cows across the US.

The health agency draws on data from wastewater sampling sites that have tested positive for influenza A.

The newly-curated dashboard, released on Tuesday, presents the data in map form and compares positive tests in a region to the same time last year.

As of 4 May, the dashboard shows that higher-than-average levels of the virus have been detected at 189 wastewater sites across the country.

Upticks, however, do not necessarily mean that bird flu has passed between animals and humans as type A cases of flu are prevalent and make up approximately 70 per cent of cases in people. According to the CDC, no unusual upticks in flu-like illnesses have been recorded in recent weeks.

The dashboard can’t yet distinguish whether high levels of the virus in wastewater indicate infections in humans, cows, birds or other animals.

The CDC is monitoring influenza A infections (CDC)

It follows an outbreak of bird flu strain H5N1, a subtype of influenza A that is circulating in cattle across the US. According to the dashboard, the risk of avian flu to the public remains low.

The US Department of Health and Human Services announced last week that it would pay farms $28,000 each to allow officials on-site to test cattle for bird flu to persuade more farmers to come forward.

One location in Saline County, Kansas, showed upticks of the avian flu for this time of the year. Four herds in Kansas tested positive in April, the CDC said.

It’s unclear whether the Kansas wastewater samples were limited to human waste or whether they included runoff water from farms.

“We’d really like to understand what might be driving that influenza A increase during what we consider the lower transmission season for influenza A,” Jonathan Yoder, deputy director of the CDC’s division of infectious disease readiness and innovation, told NBC.

According to the dashboard’s latest update on Tuesday, 42 herds in nine states had been affected. States include Kansas, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota and Texas.

The CDC is currently monitoring 260 people who have been exposed to dairy cows infected with H5N1. Thirty-three have been tested; one has been diagnosed with bird flu connected with the cattle outbreak.

On 1 April, a Texas dairy worker tested positive for H5N1 and later developed a severe case of conjunctivitis and has since recovered. He marks the second ever case recorded in the US, with spread from person to person never recorded.

As it stands, the risk to the general public is low, scientists say. While cases are rare, of the 873 humans that have been infected with H5N1 globally over the past 20 years, 458 have died, according to the World Health Organisation.

Symptoms in humans can range from non-existent to very mild, all the way through to death in the instance of severe disease, according to the CDC.

Seriously, don't drink the raw milk: Social media doubles down despite bird flu outbreak

Mary Walrath-Holdridge,

USA TODAY

Tue, May 14, 2024

No, seriously, don't drink that raw milk, despite what social media may continue to tell you.

Communities online have continued to push the rising trend of seeking out raw milk for consumption in the weeks following an update on the spread of bird flu in the U.S. earlier this month.

In a press conference on May 1, the CDC, FDA and USDA revealed that recent testing on commercial dairy products detected remnants of the H5N1 bird flu virus in one in five samples. However, none contained the live virus that could sicken people and officials said testing reaffirmed that pasteurization kills the bird flu virus, making milk safe to consume.

Even so, anti-pasteurization dairy advocates have continued their crusade online, with some saying they have begun to intentionally seek out milk contaminated with H5N1 to drink to "build up" what they believe will be a "tolerance" or "immunity" to the virus.

This continued insistence on consuming raw dairy, which was already a growing trend and concern prior to the avian flu outbreak, led the CDC to issue additional warnings last week, saying "high levels of A(H5N1) virus have been found in unpasteurized (“raw”) milk" and advising that the CDC and FDA "recommend against the consumption of raw milk or raw milk products."

Bird flu outbreak: Don't drink that raw milk, no matter what social media tells you

Raw milk fans, influencers ignore FDA, CDC warnings

Raw milk has also made headlines separate from bird flu in recent months, with local health agencies putting out warnings about specific products. In Pennsylvania, officials advised those who purchased raw milk from April through early May to discard it due to Campylobacter contamination, while Washington saw an E. Colio outbreak linked to raw milk earlier this year.

Even so, those who believe the science-backed practice pasteurization, which has been used for over 100 years, is unnecessary or even harmful have continued to question such warnings, with advocacy groups like "A Campaign for Real Milk" and the "Raw Milk Institute" putting out responses claiming that illness and deaths linked to the consumption of raw milk, as well as research into the presence of H5N1 in milk, is all a "lie" or inaccurate.

The spread of these claims has led experts to express concern for consumers who may be exposed to or convinced by these messages, as the consumption of raw milk can be especially dangerous for the elderly, children, pregnant people and those with compromised immune systems.

Here's what to know about pasteurization and what it does to the products we consume:

Close up of raw milk being poured into container at dairy farm.

Chicken owners: Here's how to protect your flock from bird flu outbreaks

What is pasteurization and why is it important?

Pasteurization is the process of heating milk to a high enough temperature for a long enough time to kill harmful germs, according to the CDC.

The process of pasteurization became routine in the commercial milk supply in the U.S. in the 1920s and was widespread by the 1950s. As a result, illnesses commonly spread via milk became less prevalent.

While misinformation about the process has led some to believe that pasteurized milk is less nutritious or better for people with lactose intolerance, pasteurization does not significantly compromise the nutritional value or content of milk. In some states, selling raw milk directly to a consumer is illegal.

Raw milk pouring from the pot to milk strainer filter and flowing in to the milk boiling pan or pot.

What can happen if you consume raw dairy?

Raw milk can carry a host of harmful bacteria, including:

◾ Salmonella

◾ E. coli

◾ Listeria monocytogenes

◾ Campylobacter

◾ Coxiella burnetii

◾ Cryptosporidium

◾ Yersinia enterocolitica

◾ Staphylococcus aureus

◾ Other foodborne illness-causing bacteria

Part of the process of making dairy products in modern dairy factory is pasteurization, or the heating of milk to kill bacteria.

The presence of these can cause a variety of health issues and ailments, including:

◾ Listeriosis

◾ Typhoid fever

◾ Tuberculosis

◾ Diphtheria

◾ Q fever

◾Brucellosis

◾ Food poisoning

◾ Miscarriage

◾ Guillain-Barre syndrome

◾ Hemolytic uremic syndrome

◾ Reactive arthritis

◾ Chronic inflammatory conditions

◾ Death

Why are some social media users still pushing unpasteurized milk and dairy?

Fringe ideas of health, wellness and nutrition have become easily widespread and somewhat popular with social media.

On TikTok, many homesteading, "tradwife," "all-natural" and other self-proclaimed wellness influencers push the idea of raw milk, presenting the idea that less intervention of any kind in their food is better.

Some also claim that they have been drinking it for years without illness, that they believe drinking it has cured their lactose intolerance and other health conditions, or that the raw milk contains vital nutrients and ingredients that are done away with by pasteurization.

These claims have all long since been debunked, according to agencies including the FDA, USDA and CDC.

Some big (and controversial) names including Gwyneth Paltrow and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have even publicly touted their consumption of raw milk, pushing the misinformation mentioned above. While some cite an overall distrust of government regulations involving food, some appear to believe they are helping others improve their health or are prone to sharing anecdotal evidence.

Comments under these videos include many justifications for drinking raw milk, from "if government says it's bad for you, there's hidden health benefits they don't want you to know," to "would it help with gut health that's been wrecked by antibiotics?" to sharing phone numbers and information on where to buy it under the table.

Others also have products they're looking to sell, whether that's the milk itself or some form of nutrition/wellness/diet plan or supplement.

Some established names, such as famous author and online creator John Green, have also taken to social media platforms like TikTok to tackle these claims head-on, with many making direct responses to popular videos promoting the consumption of raw milk.

While others, like self-identified dieticians, doctors and scientists have brought their expertise to social apps in an attempt to quell the trend, though it is a common issue for users to discern who is truly qualified and who is not in such posts.

Even without concerns about bird flu, the consumption of raw milk is a well-documented risk that can and does lead to serious health consequences. The recent outbreak of H5N1 is simply another reason to ensure you are drinking properly treated milk and remaining vigilant when making decisions about food safety, experts say.

No matter how magical and all-healing users on social media claim raw milk to be, it is important to remember that science says differently.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Raw milk might not be good for you, even if social media doubles down

How fast is bird flu spreading in US cows? ‘We have no idea’

Tue, May 14, 2024

No, seriously, don't drink that raw milk, despite what social media may continue to tell you.

Communities online have continued to push the rising trend of seeking out raw milk for consumption in the weeks following an update on the spread of bird flu in the U.S. earlier this month.

In a press conference on May 1, the CDC, FDA and USDA revealed that recent testing on commercial dairy products detected remnants of the H5N1 bird flu virus in one in five samples. However, none contained the live virus that could sicken people and officials said testing reaffirmed that pasteurization kills the bird flu virus, making milk safe to consume.

Even so, anti-pasteurization dairy advocates have continued their crusade online, with some saying they have begun to intentionally seek out milk contaminated with H5N1 to drink to "build up" what they believe will be a "tolerance" or "immunity" to the virus.

This continued insistence on consuming raw dairy, which was already a growing trend and concern prior to the avian flu outbreak, led the CDC to issue additional warnings last week, saying "high levels of A(H5N1) virus have been found in unpasteurized (“raw”) milk" and advising that the CDC and FDA "recommend against the consumption of raw milk or raw milk products."

Bird flu outbreak: Don't drink that raw milk, no matter what social media tells you

Raw milk fans, influencers ignore FDA, CDC warnings

Raw milk has also made headlines separate from bird flu in recent months, with local health agencies putting out warnings about specific products. In Pennsylvania, officials advised those who purchased raw milk from April through early May to discard it due to Campylobacter contamination, while Washington saw an E. Colio outbreak linked to raw milk earlier this year.

Even so, those who believe the science-backed practice pasteurization, which has been used for over 100 years, is unnecessary or even harmful have continued to question such warnings, with advocacy groups like "A Campaign for Real Milk" and the "Raw Milk Institute" putting out responses claiming that illness and deaths linked to the consumption of raw milk, as well as research into the presence of H5N1 in milk, is all a "lie" or inaccurate.

The spread of these claims has led experts to express concern for consumers who may be exposed to or convinced by these messages, as the consumption of raw milk can be especially dangerous for the elderly, children, pregnant people and those with compromised immune systems.

Here's what to know about pasteurization and what it does to the products we consume:

Close up of raw milk being poured into container at dairy farm.

Chicken owners: Here's how to protect your flock from bird flu outbreaks

What is pasteurization and why is it important?

Pasteurization is the process of heating milk to a high enough temperature for a long enough time to kill harmful germs, according to the CDC.

The process of pasteurization became routine in the commercial milk supply in the U.S. in the 1920s and was widespread by the 1950s. As a result, illnesses commonly spread via milk became less prevalent.

While misinformation about the process has led some to believe that pasteurized milk is less nutritious or better for people with lactose intolerance, pasteurization does not significantly compromise the nutritional value or content of milk. In some states, selling raw milk directly to a consumer is illegal.

Raw milk pouring from the pot to milk strainer filter and flowing in to the milk boiling pan or pot.

What can happen if you consume raw dairy?

Raw milk can carry a host of harmful bacteria, including:

◾ Salmonella

◾ E. coli

◾ Listeria monocytogenes

◾ Campylobacter

◾ Coxiella burnetii

◾ Cryptosporidium

◾ Yersinia enterocolitica

◾ Staphylococcus aureus

◾ Other foodborne illness-causing bacteria

Part of the process of making dairy products in modern dairy factory is pasteurization, or the heating of milk to kill bacteria.

The presence of these can cause a variety of health issues and ailments, including:

◾ Listeriosis

◾ Typhoid fever

◾ Tuberculosis

◾ Diphtheria

◾ Q fever

◾Brucellosis

◾ Food poisoning

◾ Miscarriage

◾ Guillain-Barre syndrome

◾ Hemolytic uremic syndrome

◾ Reactive arthritis

◾ Chronic inflammatory conditions

◾ Death

Why are some social media users still pushing unpasteurized milk and dairy?

Fringe ideas of health, wellness and nutrition have become easily widespread and somewhat popular with social media.

On TikTok, many homesteading, "tradwife," "all-natural" and other self-proclaimed wellness influencers push the idea of raw milk, presenting the idea that less intervention of any kind in their food is better.

Some also claim that they have been drinking it for years without illness, that they believe drinking it has cured their lactose intolerance and other health conditions, or that the raw milk contains vital nutrients and ingredients that are done away with by pasteurization.

These claims have all long since been debunked, according to agencies including the FDA, USDA and CDC.

Some big (and controversial) names including Gwyneth Paltrow and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have even publicly touted their consumption of raw milk, pushing the misinformation mentioned above. While some cite an overall distrust of government regulations involving food, some appear to believe they are helping others improve their health or are prone to sharing anecdotal evidence.

Comments under these videos include many justifications for drinking raw milk, from "if government says it's bad for you, there's hidden health benefits they don't want you to know," to "would it help with gut health that's been wrecked by antibiotics?" to sharing phone numbers and information on where to buy it under the table.

Others also have products they're looking to sell, whether that's the milk itself or some form of nutrition/wellness/diet plan or supplement.

Some established names, such as famous author and online creator John Green, have also taken to social media platforms like TikTok to tackle these claims head-on, with many making direct responses to popular videos promoting the consumption of raw milk.

While others, like self-identified dieticians, doctors and scientists have brought their expertise to social apps in an attempt to quell the trend, though it is a common issue for users to discern who is truly qualified and who is not in such posts.

Even without concerns about bird flu, the consumption of raw milk is a well-documented risk that can and does lead to serious health consequences. The recent outbreak of H5N1 is simply another reason to ensure you are drinking properly treated milk and remaining vigilant when making decisions about food safety, experts say.

No matter how magical and all-healing users on social media claim raw milk to be, it is important to remember that science says differently.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Raw milk might not be good for you, even if social media doubles down

How fast is bird flu spreading in US cows? ‘We have no idea’

Nathaniel Weixel

Wed, May 15, 2024

Avian flu is spreading rapidly among cattle, but public health and infectious disease experts are concerned the United States is too limited in its testing, leaving an incomplete picture of the virus’s spread.

The threat to the general public is currently low, health officials say, and the country’s milk supply is safe. Just one person has been infected.

“It’s critical that we are well-positioned to test, treat, prevent this virus from spreading. I think that’s clear in everything we’re saying,” Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra told reporters recently.

But the outbreak is widespread; officials have found the virus in 42 herds across nine states. Dairy farm workers are at risk every time they are exposed to potentially infected cattle, and viral mutations could cause an outbreak, experts warn.

Cases are potentially being missed, either in people, cattle or both. In past avian flu outbreaks in other parts of the world, the virus typically kills about half the people it infects.

But even if this strain doesn’t pose a significant risk to the public, many experts see the response as the biggest test of pandemic preparedness since COVID-19.

“There are opportunities that have been missed that we could have absolutely applied from the COVID experience. I think there’s still time. We’re not in trouble yet,” said Erin Sorrell, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Bird flu was first detected in dairy cows in March, though data from viral samples showed it had been circulating in cattle for at least four months prior. That’s concerning to some experts, who said there could have been widespread human exposure and asymptomatic spread among dairy workers.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is monitoring at least 260 people for symptoms and has tested at least 30 for novel influenza A, the broad category of flu that includes H5N1. Only one positive case has been identified, a farmworker in Texas who has since recovered.

Farmers have been reluctant to allow federal health officials onto their land to test potentially infected cattle amid uncertainty about how their businesses would be impacted.

Farmworkers have also been reluctant to participate in screening, and experts said it’s likely due to a mix of fears over job loss, immigration status, language barriers and general distrust in public health systems.

“They are socioeconomically vulnerable. … In some circumstances, it kind of requires the buy-in of the employer to engage in surveillance of these workers. And that hasn’t happened in a substantial way to date,” said Jessica Leibler, an environmental epidemiologist at Boston University’s school of public health.

Exposure does not necessarily mean infection, but the more workers who are exposed to potentially infected cattle, the greater the risk. Each new infection in mammals provides the opportunity for the virus to mutate.

“Without testing, without surveillance, we have no idea [of the spread],” Sorrell said. “We are not able to essentially move forward with an improved approach to protecting agricultural workers from occupational exposures if we don’t understand how they were exposed, and the potential risk of additional people being exposed and infected.”

A federal order from the end of April requires mandatory testing of dairy cattle herds, but only if they are crossing state lines. CDC workers can’t conduct investigations without an invite from state or private landowners, and the agency doesn’t have the ability to require states to test within their own borders. Becerra said the CDC is engaged in ongoing discussions with multiple states about setting up field investigation.

Stacey Schultz-Cherry, an expert in animal influenza at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, said those limitations are a hindrance but officials should be able to find workarounds, such as wastewater testing.

“There are ways to do surveillance and testing on samples that can’t or maybe don’t have to be traced back to a particular area or particular farm, because people are going to be very sensitive about it,” she said.

Federal officials have been working with state veterinary and agricultural officials to do outreach to dairy farmers and producers and emphasize the need to cooperate with federal health investigations.

“It is important for the public health officials at the state level, or the state veterinarians, or state ag officials, for us, to essentially communicate that it’s in the long-term best interest of the industry and all of us to make sure that we have as much information as possible,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack told reporters in a recent briefing.

“Producers obviously look at this circumstance and they see this as an animal health issue … so they may not fully appreciate and understand the approach that public health officials need to take in the circumstance,” Vilsack said.

The agency is also for the first time offering financial incentives for farms impacted by avian flu, including reimbursement for lost milk supply from infected cows.

William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist and professor at the Vanderbilt University school of medicine, said dairy industry producers and workers don’t have the same relationship with public health as the poultry and egg industry does.

“This is new for them; they’re more edgy and concerned,” Schaffner said. “All these diplomatic overtures and discussions are going on and are being led at the local level, because that’s where personnel are more comfortable. COVID developed a political veneer, and that impeded public health. That legacy still exists, and that may influence some of the caution in the dairy industry.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

What you need to know about the bird flu outbreak, concerns about raw milk, and more

Susanne Rust

Wed, May 15, 2024

A California Department of Food and Agriculture technician performs a culture swab on a rooster to test for avian influenza. (Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

There is a bird flu outbreak going on. Here is what you need to know about it:

What is bird flu?

Bird flu is what's known as a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. The "highly pathogenic" part refers to birds, which the virus is pretty adept at killing. In virology speak, the virus is of the Influenza A type, and is called H5N1. The "H" stands for the protein Hemagglutinin (HA), of which there are 16 subtypes (H1-H16). The "N" is short for Neuraminidase (NA), of which there are 9 subtypes (N1-N9). There are many possible combinations of HA and NA proteins. The two known type A human influenza viruses are H1N1 and H3N2. (Two additional subtypes, H17N10 and H18N11, have been identified in bats).

When did this bird flu first appear?

The current strain of H5N1 circulating the globe originated in 1996, in farmed geese living in China's Guangdong province. It quickly spread to other poultry and migrating birds. By the early 2000s, it had spread across southern Asia. By 2005, it was observed in the Middle East, Africa and Europe. In 2014, it showed up in North America, but appeared to peter out here while it still raged in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. In 2021, it showed up in wild birds migrating off Canada's Atlantic coast. Since then, it has spread across North and South America.

Read more: Bird flu spreads to Southern California, infecting chickens, wild birds and other animals

What kinds of animals does bird flu effect?

Birds are the primary carriers and victims of the virus. Across the globe, hundreds of millions of wild and domestic birds have died. Since 2021, hundreds of U.S. poultry farms have had to "depopulate" millions of birds after becoming infected, presumably from sick, migrating wild birds. The virus is highly contagious among birds and has a nearly 100% fatality rate. Mammals, too have been infected and died. In most cases, these are scavenging or predatory animals that ate sick birds — and the virus has died in these animals and not become contagious between them. So far, 48 species of mammals have become infected. However, there have been a few cases in which it appears the virus may have spread between mammals, including on European fur farms, on a few South American beaches where elephant seals came to roost, and now among dairy cattle in the United States.

Read more: California wildlife is vulnerable to an avian flu ‘apocalypse.’ What is driving the spread?

Can humans get bird flu?

Since 2003, when the virus first started spreading through southern Asia, there have been 868 cases of human infection with H5N1 reported, of which 457 were fatal — a 53% case fatality rate. There have been only two cases in the U.S. In 2022, a poultry worker was infected in Colorado and suffered only mild symptoms, including fatigue. In 2024, a dairy worker was infected in Texas and complained only of conjunctivitis, or pink eye.

Why is everyone paying attention to dairy cows?

On March 25, 2024, officials announced that dairy cows in Texas had been infected with bird flu. Since then, the virus has been found in 36 herds across nine states. There are no known cases in California. It is believed that there was a single introduction of the virus from wild bird exposure (either by passive exposure, or maybe from eating contaminated feed), that probably occurred in December in Texas. The virus has since been detected in milk. A study conducted by federal researchers found that 1 in 5 milk samples collected from retail stores had the virus. It is believed that the virus may be passing between cows and that there may be cows that show no symptoms. For the most part, it seems dairy cows only suffer mild illness when infected, and milk production slows. They clear the virus after a few weeks.

Read more: 'Nobody saw this coming'; California dairies scramble to guard herds against bird flu

Is it safe to drink milk?

Yes — if it is pasteurized milk. Federal officials say the virus they have detected in pasteurized milk samples is inactive and will not cause disease. In the case of raw milk, they urge people to avoid it. That's because they have found high viral loads in raw milk samples. In addition, studies of barn cats that have consumed raw milk have reported severe consequences. In one cluster of 24 barn cats, half of them died after consuming raw milk, with others suffering blindness, neurological distress and copious nasal discharge. The virus has not been found in sour cream or cottage cheese.

Read more: Despite H5N1 bird flu outbreaks in dairy cattle, raw milk enthusiasts are uncowed

What's the situation with wastewater?

As health officials and researchers scramble to understand how widespread avian flu is in cattle and the environment, they are analyzing municipal wastewater. One team from Emory University and Stanford University looked at 190 wastewater treatment sites in 41 states. They found a surge of Influenza A virus in the last several weeks at 59 sites. This does not necessarily mean there is bird flu at these sites. However, in places where the team has gone to investigate — including three in Texas where they knew there was H5N1 in dairy cattle — they have found bird flu. Influenza A is generally seasonal in humans — peaking from late fall to early spring. The surge the researchers noticed — including at several sites in California — started after the flu season had died down. Researchers in Texas have also detected H5N1 in the wastewater of nine of 10 cities they tested, all located in Texas. The CDC is also monitoring for Influenza A at roughly 600 sites across the nation.

Read more: Flu season is over, but there is a viral surge in California wastewater. Is it avian flu?

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment