Climate Reporters Share Tips for Investigating the Fossil Fuel Industry

by Serdar Vardar • May 2, 2024

GIJN Program Director Anne Koch moderates a panel on investigating fossil fuel companies at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.

Image: Joanna DeMarco for GIJN

There is a “central contradiction” that sums up the problem of our energy consumption — and journalists’ efforts to hold the fossil fuel industry to account, observed Anne Koch, GIJN program director, at this year’s International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.“It’s a lot easier to get whistleblowers at a PR agency” than from high-level executives inside fossil fuel companies. — Amy Westervelt, Drilled podcast host

Never has the world been more in need of a scientifically-based process for transitioning away from fossil fuels, said Koch, “and at the same time, never has the fossil fuel industry tried so hard to slow down or stop that effort… They don’t want to throw away their business plans, and we rely on those fossil fuels.”

Koch led the panel discussion for “The Investigative Agenda for Climate Change Journalism: Tracking the Fossil Fuel Industry,” which was organized by GIJN and brought together prominent climate reporters who shared tips for investigating the fossil fuel industry — and explained why this work is more vital than ever.

Panelist Amy Westervelt, host of the Drilled podcast — which investigates the obstacles to meaningful action on climate change — delved into the recently updated Carbon Majors Database report, which found that a mere 57 companies are responsible for 80% of global carbon dioxide emissions since the Paris Agreement was signed in late 2015. “It’s a pretty small number of companies contributing the largest share of emissions,” she said.

Westervelt stressed the importance of investigating state-owned fossil fuel companies such as Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi’s Adnoc, and Norway’s Equinor, which have significantly increased production compared to private or investor-owned companies. “It’s very hard to investigate state-owned oil companies, but we need to figure out a way to do it because increasingly, they’re becoming the lion’s share of this problem,” explained Westervelt. Fossil fuel majors also invest heavily in influencing policy and shaping favorable outcomes.

She also noted that carbon capture — the practice of capturing and transferring carbon emissions from large power sources to be applied elsewhere and is often touted as a climate solution — actually leads to more resource extraction because about 80% of captured carbon is then used to get more oil out of the ground. “How that became a climate solution is a mystery,” she added.

Fossil Fuel ‘Enablers’

Amy Westerveld, climate reporter and host of the Drilled podcast. Image: Joanna DeMarco for GIJN

One strategy for investigating fossil fuel companies is to uncover government ties to the industry, and Westervelt shared a method for getting started: Obtaining government representatives’ calendars and tracking their meetings with fossil fuel companies and lobbyists — and how many meetings they have with lobbyists from that industry compared to others.

She also recommended that journalists explore the “enabling industries” — companies engaged in public relations, insurance, lobbying, and consulting work for fossil fuel giants. This includes financial institutions that support major polluters. “There’s an entire ecosystem of enablers around the oil and gas industry,” she said. These industries play a significant role in shaping policy outcomes and should also be held accountable.

Disillusioned employees in these industries willing to blow the whistle have been a crucial source for Westervelt’s reporting. “It’s a lot easier to get whistleblowers at a PR agency,” than from high-level executives inside fossil fuel companies, she explained, “because most of the people working for these entities did not think that they were starting careers to carry water for a fossil fuel company that wanted to lie about climate change.”

The Problem with Carbon Credits and Net Zero

Andrés Bermúdez Liévano, an editor and reporter at the Costa Rica-based El Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) agreed that whistleblowers are a crucial source for covering the industry, and urged journalists to think creatively to seek them out. (In another IJF24 session, on pantropical investigations, Liévano revealed that experts who helped create environmental laws became his primary whistleblowers. When they realized the laws they helped create weren’t being enforced as intended, their disappointment made them important sources of information.)

There is a “central contradiction” that sums up the problem of our energy consumption — and journalists’ efforts to hold the fossil fuel industry to account, observed Anne Koch, GIJN program director, at this year’s International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.“It’s a lot easier to get whistleblowers at a PR agency” than from high-level executives inside fossil fuel companies. — Amy Westervelt, Drilled podcast host

Never has the world been more in need of a scientifically-based process for transitioning away from fossil fuels, said Koch, “and at the same time, never has the fossil fuel industry tried so hard to slow down or stop that effort… They don’t want to throw away their business plans, and we rely on those fossil fuels.”

Koch led the panel discussion for “The Investigative Agenda for Climate Change Journalism: Tracking the Fossil Fuel Industry,” which was organized by GIJN and brought together prominent climate reporters who shared tips for investigating the fossil fuel industry — and explained why this work is more vital than ever.

Panelist Amy Westervelt, host of the Drilled podcast — which investigates the obstacles to meaningful action on climate change — delved into the recently updated Carbon Majors Database report, which found that a mere 57 companies are responsible for 80% of global carbon dioxide emissions since the Paris Agreement was signed in late 2015. “It’s a pretty small number of companies contributing the largest share of emissions,” she said.

Westervelt stressed the importance of investigating state-owned fossil fuel companies such as Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi’s Adnoc, and Norway’s Equinor, which have significantly increased production compared to private or investor-owned companies. “It’s very hard to investigate state-owned oil companies, but we need to figure out a way to do it because increasingly, they’re becoming the lion’s share of this problem,” explained Westervelt. Fossil fuel majors also invest heavily in influencing policy and shaping favorable outcomes.

She also noted that carbon capture — the practice of capturing and transferring carbon emissions from large power sources to be applied elsewhere and is often touted as a climate solution — actually leads to more resource extraction because about 80% of captured carbon is then used to get more oil out of the ground. “How that became a climate solution is a mystery,” she added.

Fossil Fuel ‘Enablers’

Amy Westerveld, climate reporter and host of the Drilled podcast. Image: Joanna DeMarco for GIJN

One strategy for investigating fossil fuel companies is to uncover government ties to the industry, and Westervelt shared a method for getting started: Obtaining government representatives’ calendars and tracking their meetings with fossil fuel companies and lobbyists — and how many meetings they have with lobbyists from that industry compared to others.

She also recommended that journalists explore the “enabling industries” — companies engaged in public relations, insurance, lobbying, and consulting work for fossil fuel giants. This includes financial institutions that support major polluters. “There’s an entire ecosystem of enablers around the oil and gas industry,” she said. These industries play a significant role in shaping policy outcomes and should also be held accountable.

Disillusioned employees in these industries willing to blow the whistle have been a crucial source for Westervelt’s reporting. “It’s a lot easier to get whistleblowers at a PR agency,” than from high-level executives inside fossil fuel companies, she explained, “because most of the people working for these entities did not think that they were starting careers to carry water for a fossil fuel company that wanted to lie about climate change.”

The Problem with Carbon Credits and Net Zero

Andrés Bermúdez Liévano, an editor and reporter at the Costa Rica-based El Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) agreed that whistleblowers are a crucial source for covering the industry, and urged journalists to think creatively to seek them out. (In another IJF24 session, on pantropical investigations, Liévano revealed that experts who helped create environmental laws became his primary whistleblowers. When they realized the laws they helped create weren’t being enforced as intended, their disappointment made them important sources of information.)

Andrés Bermúdez Liévano of Costa Rica-based El Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP). Image: Joanna DeMarco for GIJN

Liévano also said it’s important to investigate carbon offset projects because they can actually contribute to the growth of the fossil fuel industry, and pointed out that the ability to “sell net zero oil” through these schemes enables fossil fuel production to increase and for those companies to continue business as usual.

To illustrate his point, Liévano mentioned pop star Taylor Swift, who thanks to her use of private jets reportedly racks up the highest carbon emissions worldwide among celebrities using private planes. “She flew from Tokyo to Las Vegas to watch her boyfriend win the Super Bowl, but she claims to be net zero,” said Liévano. “The way she can [make this claim] is through buying carbon credits and offsetting her carbon footprint. And fossil fuel companies do that on a much larger scale.”

When it comes to investigating carbon credit projects, “the devil is usually in the details,” Liévano observed. He pointed out that many of these carbon offsett projects are not working as they should, citing a recent CLIP investigation into a carbon credit project in the páramos, high-altitude moorlands in Colombia near the Ecuadorian border.

“It is a very important ecosystem in Andean countries, and it’s an Indigenous community where 99% of the community had no idea that they were part of a carbon credit scheme… This project had already sold 350,000 credits to Chevron,” explained Liévano. Nobody from the community had been consulted, and nobody knows where the money credits went. “We even found a gigantic conflict of interest. The businesswoman… running the project hired her former company to audit the project.”Journalists shouldn’t forget about sectors such as cement, steel, and others that “fly under the radar” despite contributing significantly to emissions.

The panelists agreed that such wrongdoing is widespread in carbon credit projects. Liévano stressed that there is a steep learning curve for anyone starting to investigate carbon credits, but added: “We can shorten this curve by radical collaboration. We can learn from each other. There are many specialized NGOs and journalist communities willing to share their knowledge and experiences.”

Fact-Checking Climate Change Promises

Ajit Niranjan, the Guardian’s European environment correspondent, shared sobering statistics about global progress towards climate change goals. “The total spending on clean energy projects from the global oil and gas industry is only about 2.5% of their revenue. I think that does also include carbon capture projects,” he explained. “The International Energy Agency calculated that by 2030 that should be about 50% if we want to stay on track for 1.5°C,” he said, referring to the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global surface warming below that threshold temperature.

There are many companies responsible for these greenhouse gas emissions that are not facing enough pressure, Niranjan emphasized. “One thing to consider is how we define the fossil fuel industry. It’s not just about the companies drilling for oil or mining coal… They argue that if they don’t do it, someone else will,” he said.

Ajit Niranjan, European environment correspondent for the Guardian. Image: Joanna DeMarco for GIJN

“And, while this doesn’t excuse their lobbying or influence on government policy, there is a point to be made about the demand from other sectors like airlines, car manufacturers, and others. If these industries don’t transition to cleaner practices, we won’t solve the problem.”

Journalists should naturally focus on major oil and gas companies, but shouldn’t forget about sectors such as cement, steel, and others that “fly under the radar” despite contributing significantly to emissions, Niranjan added.

‘Creative Carbon Accounting’

Sunita Narain, director general of the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi, joined the panel via video call. She emphasized that while investigating the greenwashing efforts of fossil fuel companies is important, “the larger part [for investigative journalists to play] is holding governments to account for inaction… all over the world.” Some hard climate justice questions also need to be answered, she said, such as: Who needs fossil fuels? Does Africa have the right to use its fossil fuels? Does Europe have the right to extract them?

Sunita Narain, Director General of the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi, joined via video link. Image: Joanne DeMarco for GIJN

She also highlighted the critical role of financing in climate justice, advocating for scrutiny into whether financial assistance comes as grants or adds to countries’ debt burdens during transitions away from fossil fuels, and stressed the need for effective financial systems to support green transitions and adaptation efforts in impoverished nations grappling with climate change impacts.

Narain also shared some of the challenges she has faced investigating carbon credit projects in India, and the creative methods companies used to stonewall her team. “One of the top carbon credit companies wrote to us that they could not talk to us because they were in a “period of silence,” — a meditative practice associated with yoga. “A French company had the temerity to write to us that we could not visit their project sites in South India because it was dangerous and there were bad roads, bad connectivity, and insurgencies.”

The projects and companies she investigated went to great lengths to avoid scrutiny, she observed, but she added that despite facing numerous obstacles, investigative journalists are “like a dog with a bone,” and keep drilling down to put the story together.

Watch the full IJF panel video below.

Serdar Vardar is an investigative journalist with a political science degree from the University of Buenos Aires. After living more than a decade in South America he moved to Germany to cover Turkey and global environmental stories for Deutsche Welle. Vardar was part of ICIJ’s global Pandora Papers and Shadow Diplomats investigations.

RELATED RESOURCES

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Carbon Offsets

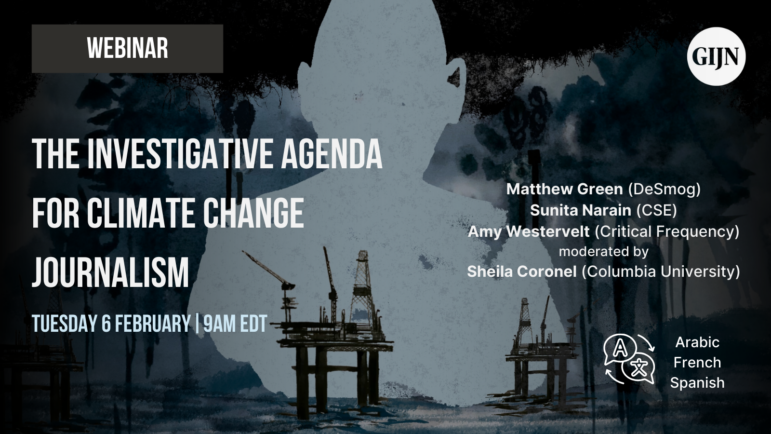

Webinar: The Investigative Agenda for Climate Change Journalism

Reporting Guide to Holding Governments Accountable for Climate Change Pledges

The Investigative Agenda for Climate ChangeExplore the Resource Center →

No comments:

Post a Comment