It is not surprising that Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, an eminent paleontologist, got himself in trouble with church officials and his Jesuit superiors.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) was a French philosopher and Jesuit priest who developed the Omega Point concept. (Illustration by Prisma/UIG photo)

May 13, 2024

By Thomas Reese

(RNS) — In the history of the Catholic Church, too many innovative thinkers were persecuted before they were accepted and then embraced by the church.

The list includes St. Thomas Aquinas (whose books were burned by the bishop of Paris), St. Ignatius Loyola (who was investigated by the Spanish Inquisition) and St. Mary MacKillop (an Australian nun who was excommunicated by her bishop for uncovering and reporting clergy child sex abuse).

It’s not surprising, then, that a French Jesuit scientist, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who tried to bridge the gap between faith and science, got himself in trouble with church officials and his Jesuit superiors in the 20th century. Only after his death was he recognized as the inspired genius that he was.

His story is magnificently told in a new PBS documentary, “Teilhard: Visionary Scientist,” which was produced by Frank Frost Productions in a 13-year labor of love. It took Frank and Mary Frost to four countries on three continents, a total of 25 locations, and included more than 35 interviews.

RELATED: Excommunication is not the church’s equivalent of capital punishment

Teilhard was born in 1881, entered the Jesuits in 1899 and was ordained a priest in 1911. His father nurtured in him a scientific curiosity, and he studied geology, botany and zoology at the University of Paris, ultimately becoming an eminent paleontologist who was involved in the discovery of the Peking Man.

If he had stuck to science, he would have led the quiet life of a scholar, but it was his attempt to bring together science and faith that got him in trouble. He went beyond the traditional argument that faith and science were not in conflict and used science as an input to theology and spirituality. Thus, his writings on Christ were enhanced by an evolutionary perspective.

He was not allowed to publish during his lifetime, although some manuscripts did circulate among friends and colleagues. Luckily, his literary executors were laypeople, not Jesuits, or his papers would have been buried in the archives.

After his death in New York City, “The Phenomenon of Man” (1955) and “The Divine Milieu” (1957) were published, leading to a condemnation of his writing by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1962.

His influence grew at and after the Second Vatican Council. Even Benedict XVI picked up on his thinking in an Easter homily where the pope spoke of the risen Christ as the next step in human evolution.

Teilhard believed that “(s)omeday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for the second time in the history of the world, we will have discovered fire.”

“Teilhard: Visionary Scientist” tells this story well, with historical photos and onsite video of places where Teilhard lived and worked, including China. His important influence on theology is revealed through interviews with theologians and others who have been touched by his writings.

The film is a great opportunity to learn about a man who is still influencing the development of theology today.

“Teilhard: Visionary Scientist” will premiere on Maryland Public Television on May 19 and be available for national and international streaming for two years, beginning on May 20, on the free PBS app.

RELATED: New Vatican document combines modern transparency with eternal teaching

Another PBS documentary being released this month is “Hollywood Priest: The Story of Fr. ‘Bud’ Kieser” by Paulist Productions, which is also working on “Statue of Limitations: Father Serra and the California Natives.”

Silicon Valley bishop, two Catholic AI experts weigh in on AI evangelization

Catholic leaders who have worked with the Vatican on AI say that a recent experiment from Catholic Answers illustrates the ways AI evangelization can go wrong.

Justin, formerly Father Justin, is an artificial intelligence virtual apologist created by Catholic Answers. (Screen grab)

May 6, 2024

By Aleja Hertzler-McCain

(RNS) — It took a little more than a day for Father Justin, an artificial intelligence avatar posing as a priest, to be defrocked. After Catholic Answers, a site devoted to evangelizing for Catholicism, introduced the character to answer questions about the faith, Catholics on social media called the character a “scandalizing mockery of the sacred priesthood” that offered only “a substitute for real interaction.”

On April 24, Catholic Answers apologized for the experiment, and Justin was reintroduced as a lay theologian.

Catholics close to the Vatican’s work on artificial intelligence say that Justin captures the possible problems with AI evangelization and the reasons for caution in Pope Francis’ and other church officials’ attempts to tackle AI, even as the technology is becoming an increasingly buzzy topic at the Vatican.

The Rev. Philip Larrey. (Photo courtesy Boston College)

The Rev. Philip Larrey, a professor in the department of formative education at Boston College, said that while he thinks Catholic Answers are a good group, “they were a little bit too quick to enter into something which is extremely complicated, and that is interactive artificial intelligence.”

San Jose, California, Bishop Oscar Cantú, who leads the Catholic faithful in Silicon Valley, said that AI doesn’t come up much with parishioners in his diocese. Nonetheless, as a leader in the computing capital of the world, Cantú said he has engaged with AI as a global and moral issue, even if he hasn’t “delved into it too much.”

Pointing to the adage coined by Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg, “move fast and break things,” the bishop said, “with AI, we need to move very cautiously and slowly and try not to break things. The things we would be breaking are human lives and reputations.”

RELATED: The Catholic Church wants to have a say on the future of AI

Experts agreed that Father Justin’s imitation of the sacrament of confession was highly inappropriate.

Cantú said, “If we have some sort of a robot in the guise of a priest, it can confuse” people about the fact that the sacraments must be celebrated in person. “Just because Father Justin recites the formula, that doesn’t make it a sacrament,” he said.

The bishop cautioned that AI chatbots should make very clear that they are AI. “It’s so critical that we be as transparent as possible, for the sake of the people we’re trying to guide,” Cantú added.

Even Justin introducing itself as a lay theologian is problematic. “A person who may be incredibly knowledgeable of Scripture and of church teaching but is not a person of faith does not do theology, because theology begins with faith,” the bishop said.

Bishop Oscar Cantú. (Photo courtesy Creative Commons)

Noreen Herzfeld, a professor of theology and computer science at St. John’s University and the College of St. Benedict and one of the editors of a book about AI sponsored by the Vatican Dicastery for Culture and Education, said that the AI character was previously “impersonating a priest, which is considered a very serious sin in Catholicism.”

The leaders don’t dismiss the usefulness of AI when used properly. Cantú said that AI can do “tremendous work” as “a tool that can be used for good for doing research.” But, he added, “A person of faith doing theology then needs to judge the credibility of each source and the authority of each source.”

Larrey, who has worked closely with both Vatican and AI leaders on the ethical issues surrounding AI, emphasized that Pope Francis is interested in “person-centered AI,” meaning that AI must be used “for the good of human beings” and “not the detriment of people.”

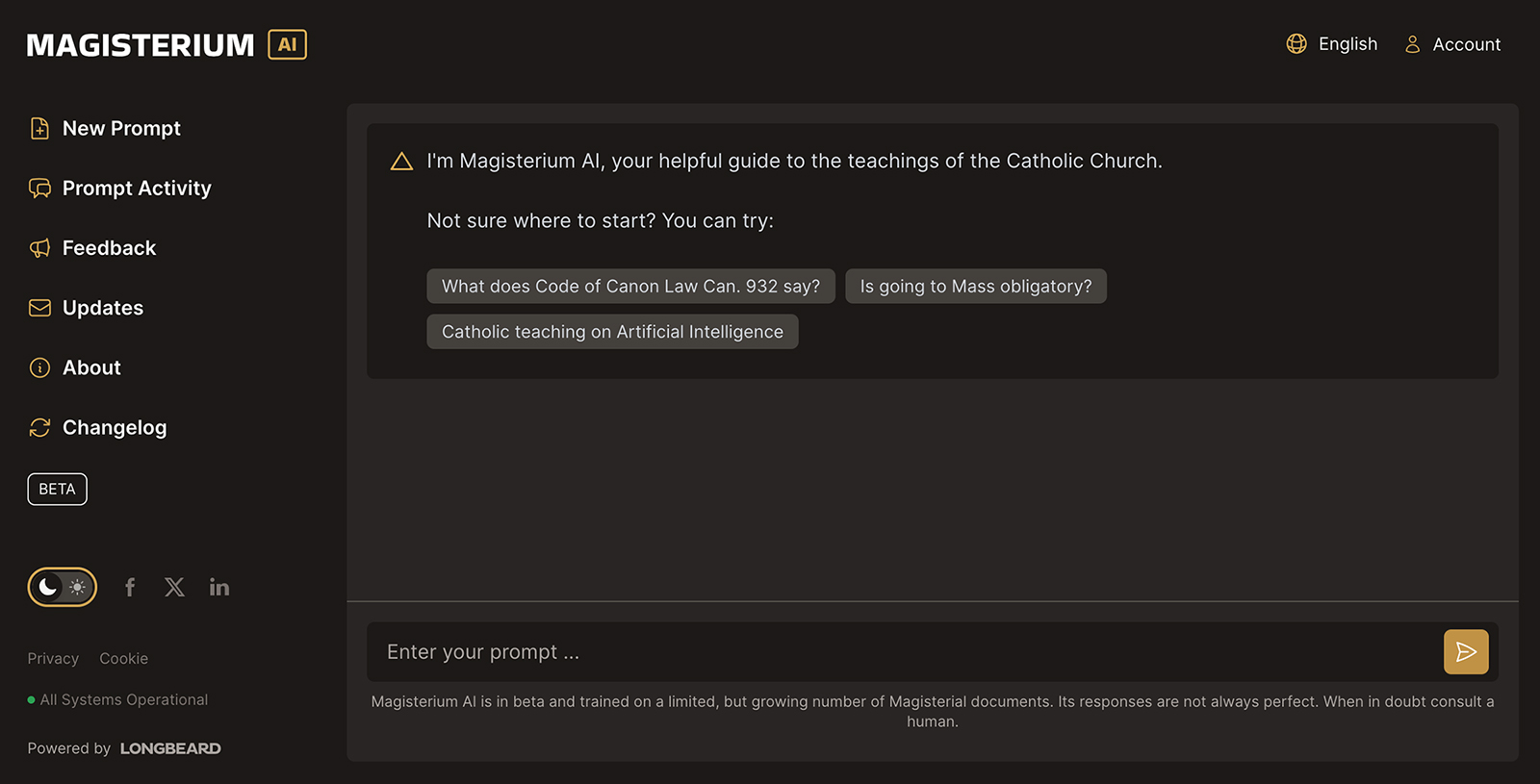

The best example of AI being used for evangelization, Larrey said, is Magisterium AI, a chatbot developed by Longbeard, a digital strategy firm founded by a former seminarian named Matthew Harvey Sanders, a friend of Larrey’s. The bot explains church teaching in a format like ChatGPT, by drawing on official church teachings, as well as select writings such as the works of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, linking to the documents that informed its answer.

Larrey distinguishes such automated research from generative AI, which learns and experiments with its newfound knowledge. “When you have a generative AI, if you’re not careful, it gets out of hand,” he said.

Accuracy issues, Herzfeld said, is one of many reasons it should not be used for evangelization. “As much as you beta test one of these chatbots, you will never get rid of hallucinations” — moments when the AI makes up its own answers, she said.

The Magisterium AI interface. (Screen grab)

“The problem is actually built into how they work,” Herzfeld continued. “They work on statistics, on probabilities as to what words and phrases should follow, and they do not have internal mental models of the world. And without that, they will always get off track.”

Herzfeld said that an AI is only as good as the data it is trained on. On issues where the church is divided, she said, “I could see bots out there giving competing answers, for example, on the desirability of the Latin Mass or the role of women in the church.”

Herzfeld expressed concern, too, that people who are not well-versed in technology may believe computers have a “certain level of infallibility,” and she worries that turning to AI bots will lead to spiritual “de-skilling,” convincing young people to think “religion is just about answers.”

“When I was their age, I was shy, and if I’d had a bot to answer my questions, I’d have gone to a bot instead of going to my pastor or even going to my parents to ask questions about religion,” Herzfeld said, adding that forming relationships with AI instead of with other people or God could become a type of idolatry.

Larrey, who has been studying AI for nearly 30 years and is in conversation with Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, is optimistic that the technology will improve. He said Altman is already making progress on the hallucinations, on its challenges to users’ privacy and reducing its energy use — a recent analysis estimated that by 2027, artificial intelligence could suck up as much electricity as the population of Argentina or the Netherlands.

Larrey understands that Catholic Answers’ Justin was designed to “get people who would otherwise not be interested in the Catholic faith,” but also thinks chatbots should not vie with real priests. “Why don’t you just go down to your parish and talk to a priest? They’re not extinct, you know,” he said.

For evangelization, “I think you need people to contact and to attract other people,” said Larrey. “We will never eliminate that step.”

Cantú believes this is the ultimate lesson to be drawn from the ill-fated Father Justin. “The faith is not just about answers. It’s not just about information. It’s about encounter, a personal encounter with Christ, with real people,” he said.

RELATED: Artificial intelligence program poised to shake up Catholic education, doctrine

Just as rank-and-file Catholics should exercise caution with AI for evangelization, Cantú suggested similar care from priests who might turn to ChatGPT for an assist when writing their homilies.

While the AI’s suggestion can be a good starting point for priests who are “pressed for time,” Cantú said, the priest must make the homily his own.

“When anyone within the church, a person of faith, expresses the truth, to some degree, they’re opening a window to the mind of God because God is truth.” In the end, the bishop said, “It has to be my words and my act of faith.

“A robot can’t do that because it’s not an act of faith.”

No comments:

Post a Comment