David Lynch,

PA Political Staff

Wed, 15 May 2024

A cutting-edge new weapon which uses radio waves to blast drones out of the sky is under development for the UK’s armed forces.

The Radio Frequency Directed Energy Weapon (RFDEW) beams radio waves to disrupt or damage the critical electronic components of vehicles and drones used by enemy combatants, which can cause them to stop in their tracks or fall out of the sky.

It can be used across land, air and sea and has a range of up to 1km, which could be extended in the future.

Release of information about the new weapon comes after Prime Minister Rishi Sunak promised to hike UK defence spending to 2.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2030.

The Radio Frequency Directed Energy Weapon (RFDEW) that beams radio waves to disrupt or damage the critical electronic components of vehicles and drones used by enemy combatants (MoD Crown Copyright/PA)

With an estimated cost of 10p per radio wave shot, the technology is also being billed as a cost-effective alternative to traditional missiles, and could be used to take down dangerous drone swarms.

The technology can be mounted on to a variety of military vehicles, and uses a mobile power source to produce pulses of a radio frequency energy in a beam that can fire sequenced shots at a single target or be broadened to hit a series of targets.

Minister for defence procurement James Cartlidge said: “We are already a force to be reckoned with on science and technology, and developments like RFDEW not only make our personnel more lethal and better protected on the battlefield, but also keep the UK a world leader on innovative military kit.

“The war in Ukraine has shown us the importance of deploying uncrewed systems, but we must be able to defend against them too. As we ramp up our defence spending in the coming years, our Defence Drone Strategy will ensure we are at the forefront of this warfighting evolution.”

The new weapons system will undergo extensive testing with British soldiers over the summer.

It is being developed by a joint team from the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) and Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S), working with UK industry under Project Hersa.

DSTL chief executive Paul Hollinshead said: “These game-changing systems will deliver decisive operational advantage to the UK armed forces, saving lives and defeating deadly threats.

“World-class capabilities such as this are only possible because of decades of research, expertise and investment in science and technology at DSTL and our partners in UK industry.”

Wed, 15 May 2024

A cutting-edge new weapon which uses radio waves to blast drones out of the sky is under development for the UK’s armed forces.

The Radio Frequency Directed Energy Weapon (RFDEW) beams radio waves to disrupt or damage the critical electronic components of vehicles and drones used by enemy combatants, which can cause them to stop in their tracks or fall out of the sky.

It can be used across land, air and sea and has a range of up to 1km, which could be extended in the future.

Release of information about the new weapon comes after Prime Minister Rishi Sunak promised to hike UK defence spending to 2.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2030.

The Radio Frequency Directed Energy Weapon (RFDEW) that beams radio waves to disrupt or damage the critical electronic components of vehicles and drones used by enemy combatants (MoD Crown Copyright/PA)

With an estimated cost of 10p per radio wave shot, the technology is also being billed as a cost-effective alternative to traditional missiles, and could be used to take down dangerous drone swarms.

The technology can be mounted on to a variety of military vehicles, and uses a mobile power source to produce pulses of a radio frequency energy in a beam that can fire sequenced shots at a single target or be broadened to hit a series of targets.

Minister for defence procurement James Cartlidge said: “We are already a force to be reckoned with on science and technology, and developments like RFDEW not only make our personnel more lethal and better protected on the battlefield, but also keep the UK a world leader on innovative military kit.

“The war in Ukraine has shown us the importance of deploying uncrewed systems, but we must be able to defend against them too. As we ramp up our defence spending in the coming years, our Defence Drone Strategy will ensure we are at the forefront of this warfighting evolution.”

The new weapons system will undergo extensive testing with British soldiers over the summer.

It is being developed by a joint team from the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) and Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S), working with UK industry under Project Hersa.

DSTL chief executive Paul Hollinshead said: “These game-changing systems will deliver decisive operational advantage to the UK armed forces, saving lives and defeating deadly threats.

“World-class capabilities such as this are only possible because of decades of research, expertise and investment in science and technology at DSTL and our partners in UK industry.”

China navy secretly built what could be world's first drone aircraft carrier: report

Thibault Spirlet

Russia can't seem to stop this Ukrainian Cessna-style drone that, compared to missiles, is basically a 'flying brick' with a bomb onboard

Jake Epstein

"Once you have countermeasures in place, it should be really easy to shoot this thing down," Hoffmann said. "And the problem is they don't appear to have that."

But establishing adequate countermeasures to consistently and effectively defend against low-altitude, slow-moving threats can be a challenge, and not just for Russia, explained Gordon Davis Jr., a retired US Army major general.

"That's a vulnerability at the moment that the Ukrainians are exploiting to their advantage," Davis, a non-resident senior fellow with the transatlantic defense and security program at the Center for European Policy Analysis, said at an event on drone warfare this week.

Notably, the Cessna-style drone underscores the success of Ukraine's ever-evolving drone program. Since the war began more than two years ago, Kyiv has developed a robust arsenal of homemade, unmanned systems that are capable of long-range strikes on Russian targets in the sea and on the ground.

These unique weapons have proven to be an invaluable component of Ukraine's war efforts, especially in recent months as the country continues to face some restrictions by Western countries on how to use their military assistance.

The US, for example, has said that it does not want Kyiv to use American-made weaponry to conduct strikes on Russia's sovereign territory, fearing that it could escalate the war. Instead, Washington wants its long-range munitions to be limited to use in Russian-occupied territory of Ukraine. This has so far been the case.

"They're leveraging their domestic capabilities to good advantage, and to strike key infrastructure within Russia," Davis said.

Lance Landrum, a retired US Air Force lieutenant general and another non-resident senior fellow with CEPA's transatlantic defense and security program, hailed the Cessna-style drones as just one example of Ukraine's "innovation and creativity."

"That's one thing about these drones of all different sizes — the small, medium, and large — they can exploit gaps and seams in traditional air-defense systems in ways that traditional offensive systems haven't in the past," Landrum said at the CEPA event.

Opinion

The US and Royal Navies have lost the ability to introduce new ships

Tom Sharpe

Wed, May 15, 2024

The Royal Navy and the US Navy can fairly be described as the leading maritime forces of the Western world – though realistically, of course, the USN is in a class by itself.

Both services can deploy fifth-generation fighters from aircraft carriers. Both can launch Tomahawk cruise missiles at targets a thousand miles away. Both have now proven that they can shoot down incoming ballistic missiles, in historic engagements against the Iran-backed Houthis of Yemen. Though the USN is far bigger, both navies can do the rest of the top-tier missions: nuclear submarine deterrence, attack, and covert ops; effective anti-submarine warfare (an area in which the Royal Navy is sometimes, for once, a little ahead); and amphibious assault. Or anyway the USN can do amphibious assault and the Royal Navy – actually the Royal Fleet Auxiliary – will be able to soon.

But both services have their problems, in particular with introducing new ships.

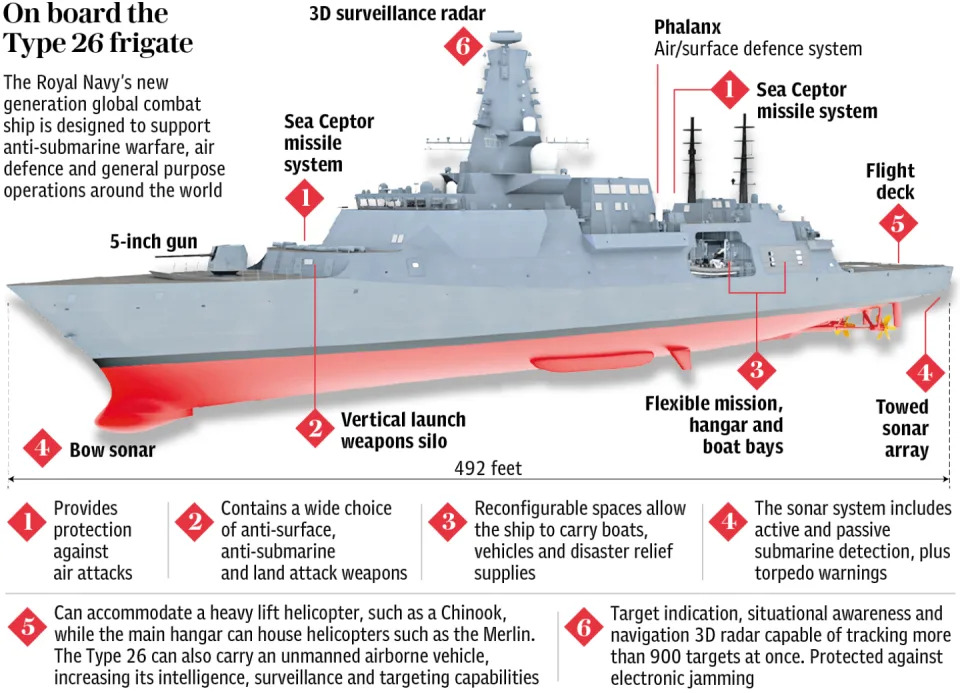

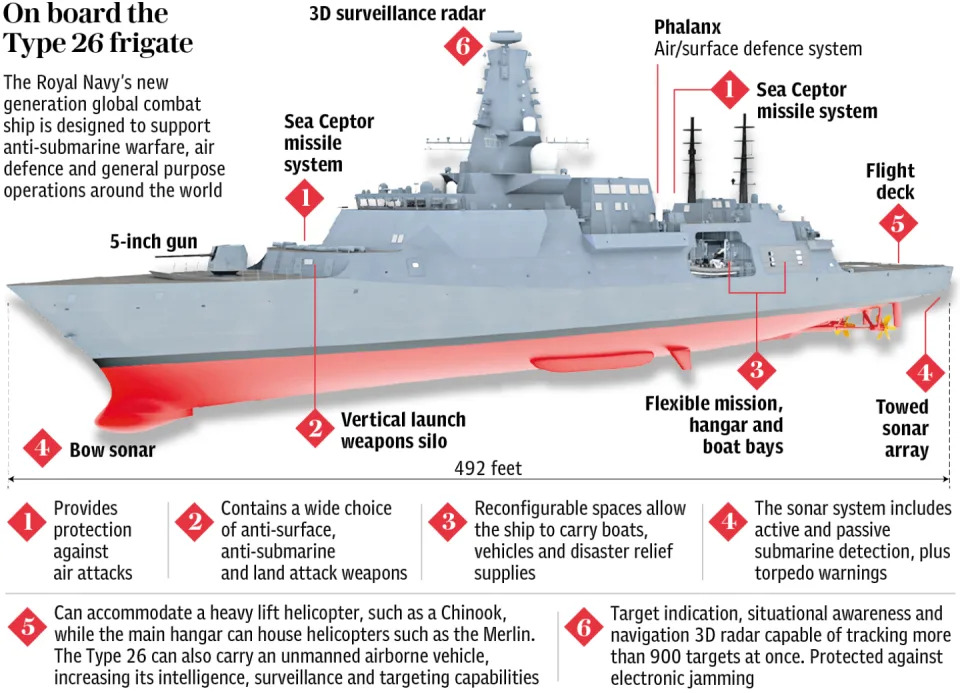

Here in Britain, the problems are obscured because planned shipbuilding numbers are good. The new Dreadnought class deterrent submarines are in train as are the last of the Astute class attack submarines. The collaboration with the US and Australia for the next generation of attack submarines remains sound, although that is a long way away and many hurdles remain. The Type 26 and 31 Frigates are (finally) progressing nicely and the news that they will both have Mark 41 vertical launchers, able to carry effective American missiles of all kinds, is welcome.

The fact that, to my mind, takes a little bit of the gold leaf off ‘the golden age of shipbuilding’ here in the UK is the number of ships that are being asked to run on beyond their programmed lifespan because these projects all started too late. Resource constraints make getting programs across the line so difficult that we are now seemingly incapable of starting a complex build programme in time for it to be finished as the previous class pays off. Delays in build due to politics, shipyard capacity issues and design tinkering all compound this. Capability gaps are now the norm, sometimes huge ones.

The venerable Type 23 frigates typify this. They were built in the 1990s and Noughties and were designed to run reasonably low-intensity towed array patrols in the North Atlantic with a life span of 18 to 20 years. Even the very newest (and best) one, my old command HMS St Albans – just coming out of an extended maintenance period – is already 24 years old. They will all be in their late 30s by the time the T26s are ready to relieve them.

Running ships on past their designed life like this creates two problems. First is the cost of keeping them mechanically sound and safe to operate. The refits cost more than it cost to build them. Second, you are forced to throw money at what in technological terms is now an ‘old ship’. The latest advancements in weapons, sensors, AI, communications and satellite networks – all the things we are working so hard to develop to retain a technological edge – become increasingly incompatible with the ageing platforms.

The USN's futuristic Zumwalt class destroyer has not been a success. Only three will ever join the fleet - US Navy/Getty

Older ships also use more people, the reason I am confident we won’t see our two Royal Navy amphibious assault ships on operations anytime soon, despite the announcement that they will not be paid off early.

It’s doubly frustrating that we are in the middle of making the same mistake again with the replacement for the Type 45 destroyers. HMS Daring, first of class, was launched in 2006 and should therefore be expecting to retire in 2036 at the latest. If the Type 45 replacement is to be ready in time, designs need to be mature now and contracts awarded straight away.

To give an idea, steel was first cut on the Type 26 Frigate in July 2017 but that ship won’t reach initial operating capability until October 2028. But that was on the back of a further seven years of contract discussions and awards, i.e. it took 18 years from ‘concept’ to ‘operational’.

Meanwhile, over in the US, the Zumwalt class was a case study of what happens if you try to pack too much new and untested technology into one hull. The initial plan was to build 32 but as the costs skyrocketed, this reduced to 24, then to seven. The USN has ended up with three. A related case was the Seawolf submarines, which are powerful but horrendously costly. Again, the USN only got three, though in this case the more reasonably priced Virginia class successor project has been a great success.

With surface ships the USN did not recover as well – if at all. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) is perhaps the exemplar of a programme that started with a confused concept of operations, was rushed into production, and got worse from there. It took about 12 years from launch before they were universally being referred to as ‘little crappy ships’. Needless to say, the US Navy hasn’t let the almost unarmed LCSs anywhere near the current littoral combat theatre in the Southern Red Sea.

And now the Constellation class frigate, the US answer to our Type 26, is also in a bit of a mess. On this occasion, the USN took the excellent and proven Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM) design and rather than modifying 15 per cent of it for US purposes as initially stated, modified 85 per cent. It’s basically a new ship. A combination of this meddling and workforce shortfalls in the yard where it is being built have caused delays and a price hike.

So ‘too expensive’, ‘unreliable’ and ‘fiddled with too much’ in sequential order. It’s almost as though the USN can’t build new surface combatant warships at all any more. Fortunately, in the long running Arleigh Burke destroyer programme, the US not only produced one of the best warships ever at the start, it is also one of the most modifiable. The latest ones, still coming off the line, physically resemble their forebears of 33 years ago but that’s about it: and the old ones still in service have been upgraded in line with the new ones.

Arleigh Burke class. When you get something right, keep doing it - MC3 Lasheba James/US Navy/AFP/Getty

Here in Britain our replacement air defence destroyer, the Type 83, will need to avoid all these traps. It will need to be advanced (but not too much), have what is meant to be inked in from the start and then not be tinkered with during build.

That’s not going to be easy, however. The things an air defence destroyer needs to be able to do are expanding and shifting at pace. The Future Air Dominance System (FADS) is the collective term for this and whilst accelerating fast, the concept is still in its infancy.

Whatever FADS ends up being, it will need to be advanced but not too expensive. It must be survivable and not have too many people onboard. It must carry lots of (reloadable at sea) missiles but not be too big and expensive. It will need to counter swarm attacks by cheap and simple drones or missiles (the forthcoming Dragonfire laser should be useful here). It will also need to shoot down ballistic missiles in space, supersonic or hypersonic missiles from the upper atmosphere to sea level, and defend against surface attack (also drones). It should be able to knock down targets below the horizon which are being tracked by something else such as an airborne radar aircraft.

The Red Sea has confirmed beyond doubt that warships need to be able to strike targets ashore – add this to the list, though most navies apart from the Royal Navy had already done so. The Type 83s will need to be able to conduct disaggregated operations thousands of miles from other ships but also in a task group next to the carrier (this is a key requirement).

These are complex and sometimes conflicting requirements to the point where some FADS concepts dispense with the idea of a large ship at all, relying instead on a fleet of smaller arsenal and uncrewed ships. This could work in wartime, and might even save money (never far away in the conversation) but solutions like this often overlook the 99 per cent of the time when a warship’s job is to prevent the war in the first place.

So, to my mind, peacetime operations, deterrence work, radar physics and probably a pinch of traditionalism means that FADS will still have a destroyer-looking ship at its core with the option to add remotely operated or heavily armed options down the line. It won’t be a vast cruiser (see Zumwalt) or small and under-armed (see the LCS).

But FADS needs to mature now because the equation is simple: no destroyers = no carriers = no conventional deterrent in far too much of the world. And if they’re not ready in time, we know from the Type 23s what it costs to run ships beyond their expected life and given the complexities (and difficulties) of the Type 45 power train, it will be worse if we have to do it again.

So I would question the notion that we are in a golden age of shipbuilding here in the UK. If we have entered a golden anything it should be the age of budget holders finally recognising how tight things have become in the Royal Navy, how this could compromise the defence of the nation in the face of increasing threats and the demands this continually places on the service’s excellent people.

In the States the problems are less ones of lacking money and vision – the US has long had clear ideas on a powerful navy and has provided ample funds. Problems in America are ones of execution, with at least three major ship classes failing to reach service in any numbers over the last three decades – leaving the USN, like the RN, with a lot of the same ships it had 30 years ago.

The good news is that in both nations the desire is there to meet the threats of the future. The two navies now just need to be given the resources and freedom to deliver. In the specific case of the Type 83 destroyer, that time for decisive action is now.

Tom Sharpe is a former Royal Navy officer and surface combatant captain

Thibault Spirlet

BUSINESS INSIDER

Wed, May 15, 2024

China has secretly built what could be the world's first drone carrier, an analyst said.

The report pointed to the vessel's size to guess at its primary mission.

Having a drone carrier would allow China to use different types of drones to attack, an analyst told BI.

China's navy has secretly built what could be the world's first dedicated drone carrier ship, according to Naval News, a squat ship that looks like a mini-aircraft carrier.

The outlet used satellite imagery dated May 6, along with input from J. Michael Dahm, a senior resident fellow for aerospace and China studies at the Mitchell Institute.

"We are confident that this ship is the world's first dedicated fixed-wing drone carrier," it said. Other experts, however, cautioned that only time would tell its purpose.

The report cited the vessel's flight deck length, which it said is about one-third the length and half the width of a Chinese or US Navy aircraft carrier. It's also roughly half the length of China's amphibious assault ships that launch manned helicopters, suggesting that the new ship's flight deck is designed for fewer helicopters or smaller aircraft like drones.

Warships' flight decks have been bases for drones like the US's MQ-8B Fire Scout helicopter and the lightweight Scan Eagle drone. What appears new is that the Chinese ship's entire function may be to launch and land drones, although its purpose will only be confirmed by future observations of its testing and operations.

The report estimated that the flight deck was wide enough to allow aircraft or drones with a wingspan of roughly 65 feet, like the Chinese equivalents of the Reaper drone, to operate from it.

Citing satellite imagery, the report also said that the flight deck appears to be "very" low, suggesting there's no hangar below for aircraft storage and maintenance like those of assault ships and carriers. As seen, the ship appears to be well under the length of a Chinese frigate.

Alessio Patalano, a professor of war and strategy in East Asia at the Department of War Studies at King's College London, backed up the assessment.

He told BI that the platform's flattop and compact deck, together with the reportedly catamaran-like hull, suggest that it will be used for drones; the US has also experimented with launching drones from catamaran-style ferries, but the ship's flight deck is much smaller.

Patalano also said it would make sense for the Chinese navy to keep its trials largely hidden from international scrutiny.

But Lyle Goldstein, Director of Asia Engagement at the DC-based think tank Defense Priorities, said he would hesitate to call it a drone carrier based on just one satellite image.

Strategically, however, he said it would make a lot of sense.

Drones have a relatively small range, limiting their deployment away from the coastline, Goldstein told BI, so having a carrier would give the Chinese navy a "robust" network and allow drones of different types to attack.

"I spend a lot of time looking at Taiwan scenarios, and I think China would be looking to really deploy huge amounts of these exploding drones as its main weapon," he said.

The possible drone mothership was spotted only weeks after China's third carrier started sea trials.

Wed, May 15, 2024

China has secretly built what could be the world's first drone carrier, an analyst said.

The report pointed to the vessel's size to guess at its primary mission.

Having a drone carrier would allow China to use different types of drones to attack, an analyst told BI.

China's navy has secretly built what could be the world's first dedicated drone carrier ship, according to Naval News, a squat ship that looks like a mini-aircraft carrier.

The outlet used satellite imagery dated May 6, along with input from J. Michael Dahm, a senior resident fellow for aerospace and China studies at the Mitchell Institute.

"We are confident that this ship is the world's first dedicated fixed-wing drone carrier," it said. Other experts, however, cautioned that only time would tell its purpose.

The report cited the vessel's flight deck length, which it said is about one-third the length and half the width of a Chinese or US Navy aircraft carrier. It's also roughly half the length of China's amphibious assault ships that launch manned helicopters, suggesting that the new ship's flight deck is designed for fewer helicopters or smaller aircraft like drones.

Warships' flight decks have been bases for drones like the US's MQ-8B Fire Scout helicopter and the lightweight Scan Eagle drone. What appears new is that the Chinese ship's entire function may be to launch and land drones, although its purpose will only be confirmed by future observations of its testing and operations.

The report estimated that the flight deck was wide enough to allow aircraft or drones with a wingspan of roughly 65 feet, like the Chinese equivalents of the Reaper drone, to operate from it.

Citing satellite imagery, the report also said that the flight deck appears to be "very" low, suggesting there's no hangar below for aircraft storage and maintenance like those of assault ships and carriers. As seen, the ship appears to be well under the length of a Chinese frigate.

Alessio Patalano, a professor of war and strategy in East Asia at the Department of War Studies at King's College London, backed up the assessment.

He told BI that the platform's flattop and compact deck, together with the reportedly catamaran-like hull, suggest that it will be used for drones; the US has also experimented with launching drones from catamaran-style ferries, but the ship's flight deck is much smaller.

Patalano also said it would make sense for the Chinese navy to keep its trials largely hidden from international scrutiny.

But Lyle Goldstein, Director of Asia Engagement at the DC-based think tank Defense Priorities, said he would hesitate to call it a drone carrier based on just one satellite image.

Strategically, however, he said it would make a lot of sense.

Drones have a relatively small range, limiting their deployment away from the coastline, Goldstein told BI, so having a carrier would give the Chinese navy a "robust" network and allow drones of different types to attack.

"I spend a lot of time looking at Taiwan scenarios, and I think China would be looking to really deploy huge amounts of these exploding drones as its main weapon," he said.

The possible drone mothership was spotted only weeks after China's third carrier started sea trials.

Russia can't seem to stop this Ukrainian Cessna-style drone that, compared to missiles, is basically a 'flying brick' with a bomb onboard

Jake Epstein

Business Insider

Wed, May 15, 2024

Ukraine has increasingly attacked Russian military and energy facilities with long-range drones.

One weapon Ukraine has turned to is essentially a small sport aircraft packed with explosives.

Kyiv has recently relied on this Cessna-like drone to carry out at least two successful strikes.

Ukraine has in recent weeks relied on an unusual weapon to conduct strikes deep inside Russian territory: a small unmanned aircraft packed with explosives that resembles some variants of the propeller-driven Cessna aircraft.

The light, fixed-wing planes observed in attacks this spring travel at low altitudes and move significantly slower than a long-range missile might, yet they have proven capable of evading Moscow's air-defense systems and traveling unscathed for hundreds of miles to reach their targets deep in enemy territory.

Experts say these aircraft underscore the success of Ukraine's innovative long-range drone program, which Kyiv has employed to go after Russia's military and energy facilities.

In early April, Kyiv used a modified Aeroprakt A-22 Foxbat to attack a drone-making factory in the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The small, ultralight sport aircraft was developed and is manufactured in Ukraine and costs less than $90,000 per unit.

The plane can also travel at speeds up to 130 mph (much slower than a cruise missile, which can fly at speeds in excess of 500 mph, or a ballistic missile, which is significantly faster) and be configured with explosives inside the cabin.

Ukraine reportedly attempted additional strikes with drones like this later in the month, though it is unclear how successful these actually were. Last week, an aircraft that looks similar to the A-22 was spotted in an attack on an oil refinery in the Republic of Bashkortostan, even deeper inside Russia. Multiple open-source intelligence shared footage of the plane soaring unopposed over the facility.

Fabian Hoffmann, a doctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo and security expert, previously wrote that "in the world of missile systems" the aircraft is "basically a flying brick."

But while the aircraft may appear crudely put together, it's still a "rather complex weapon system" because the existing airframe and engine still need to be combined with explosives and guidance technology, he later told Business Insider in an interview.

The aircraft seems to operate at a relatively low altitude, as seen in the footage, making it more difficult for radar to track. And if Ukraine can find a corridor that lacks proper air-defense coverage, then the drone can effectively penetrate right through Russian territory, Hoffmann said. Additionally, given its design, the aircraft could also be mistaken for a civilian plane rather than a threat.

That doesn't really excuse Russia's apparent failure to engage them though. In the Tatarstan and Bashkortostan attacks, the aircraft managed to fly for several hours, hundreds of miles into Russian territory without getting shot down by Russia's formidable air-defense systems, which have been a headache for Ukrainian forces on the battlefield.

These drones are loud and slow, rendering themselves vulnerable to visual confirmation along the way, even if a radar doesn't pick them up. Hoffmann said these aircraft should be relatively easy to pick off or defend against by placing air defenses like anti-aircraft guns around critical infrastructure.

Ultimately, he said, that these systems are slipping through suggests that Russia has a capacity issue — with assets tied up either defending the battlefield or key population centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg — and may also be underestimating the Ukrainian threat.

Wed, May 15, 2024

Ukraine has increasingly attacked Russian military and energy facilities with long-range drones.

One weapon Ukraine has turned to is essentially a small sport aircraft packed with explosives.

Kyiv has recently relied on this Cessna-like drone to carry out at least two successful strikes.

Ukraine has in recent weeks relied on an unusual weapon to conduct strikes deep inside Russian territory: a small unmanned aircraft packed with explosives that resembles some variants of the propeller-driven Cessna aircraft.

The light, fixed-wing planes observed in attacks this spring travel at low altitudes and move significantly slower than a long-range missile might, yet they have proven capable of evading Moscow's air-defense systems and traveling unscathed for hundreds of miles to reach their targets deep in enemy territory.

Experts say these aircraft underscore the success of Ukraine's innovative long-range drone program, which Kyiv has employed to go after Russia's military and energy facilities.

In early April, Kyiv used a modified Aeroprakt A-22 Foxbat to attack a drone-making factory in the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The small, ultralight sport aircraft was developed and is manufactured in Ukraine and costs less than $90,000 per unit.

The plane can also travel at speeds up to 130 mph (much slower than a cruise missile, which can fly at speeds in excess of 500 mph, or a ballistic missile, which is significantly faster) and be configured with explosives inside the cabin.

Ukraine reportedly attempted additional strikes with drones like this later in the month, though it is unclear how successful these actually were. Last week, an aircraft that looks similar to the A-22 was spotted in an attack on an oil refinery in the Republic of Bashkortostan, even deeper inside Russia. Multiple open-source intelligence shared footage of the plane soaring unopposed over the facility.

Fabian Hoffmann, a doctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo and security expert, previously wrote that "in the world of missile systems" the aircraft is "basically a flying brick."

But while the aircraft may appear crudely put together, it's still a "rather complex weapon system" because the existing airframe and engine still need to be combined with explosives and guidance technology, he later told Business Insider in an interview.

The aircraft seems to operate at a relatively low altitude, as seen in the footage, making it more difficult for radar to track. And if Ukraine can find a corridor that lacks proper air-defense coverage, then the drone can effectively penetrate right through Russian territory, Hoffmann said. Additionally, given its design, the aircraft could also be mistaken for a civilian plane rather than a threat.

That doesn't really excuse Russia's apparent failure to engage them though. In the Tatarstan and Bashkortostan attacks, the aircraft managed to fly for several hours, hundreds of miles into Russian territory without getting shot down by Russia's formidable air-defense systems, which have been a headache for Ukrainian forces on the battlefield.

These drones are loud and slow, rendering themselves vulnerable to visual confirmation along the way, even if a radar doesn't pick them up. Hoffmann said these aircraft should be relatively easy to pick off or defend against by placing air defenses like anti-aircraft guns around critical infrastructure.

Ultimately, he said, that these systems are slipping through suggests that Russia has a capacity issue — with assets tied up either defending the battlefield or key population centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg — and may also be underestimating the Ukrainian threat.

"Once you have countermeasures in place, it should be really easy to shoot this thing down," Hoffmann said. "And the problem is they don't appear to have that."

But establishing adequate countermeasures to consistently and effectively defend against low-altitude, slow-moving threats can be a challenge, and not just for Russia, explained Gordon Davis Jr., a retired US Army major general.

"That's a vulnerability at the moment that the Ukrainians are exploiting to their advantage," Davis, a non-resident senior fellow with the transatlantic defense and security program at the Center for European Policy Analysis, said at an event on drone warfare this week.

Notably, the Cessna-style drone underscores the success of Ukraine's ever-evolving drone program. Since the war began more than two years ago, Kyiv has developed a robust arsenal of homemade, unmanned systems that are capable of long-range strikes on Russian targets in the sea and on the ground.

These unique weapons have proven to be an invaluable component of Ukraine's war efforts, especially in recent months as the country continues to face some restrictions by Western countries on how to use their military assistance.

The US, for example, has said that it does not want Kyiv to use American-made weaponry to conduct strikes on Russia's sovereign territory, fearing that it could escalate the war. Instead, Washington wants its long-range munitions to be limited to use in Russian-occupied territory of Ukraine. This has so far been the case.

"They're leveraging their domestic capabilities to good advantage, and to strike key infrastructure within Russia," Davis said.

Lance Landrum, a retired US Air Force lieutenant general and another non-resident senior fellow with CEPA's transatlantic defense and security program, hailed the Cessna-style drones as just one example of Ukraine's "innovation and creativity."

"That's one thing about these drones of all different sizes — the small, medium, and large — they can exploit gaps and seams in traditional air-defense systems in ways that traditional offensive systems haven't in the past," Landrum said at the CEPA event.

Opinion

The US and Royal Navies have lost the ability to introduce new ships

Tom Sharpe

Wed, May 15, 2024

The Royal Navy and the US Navy can fairly be described as the leading maritime forces of the Western world – though realistically, of course, the USN is in a class by itself.

Both services can deploy fifth-generation fighters from aircraft carriers. Both can launch Tomahawk cruise missiles at targets a thousand miles away. Both have now proven that they can shoot down incoming ballistic missiles, in historic engagements against the Iran-backed Houthis of Yemen. Though the USN is far bigger, both navies can do the rest of the top-tier missions: nuclear submarine deterrence, attack, and covert ops; effective anti-submarine warfare (an area in which the Royal Navy is sometimes, for once, a little ahead); and amphibious assault. Or anyway the USN can do amphibious assault and the Royal Navy – actually the Royal Fleet Auxiliary – will be able to soon.

But both services have their problems, in particular with introducing new ships.

Here in Britain, the problems are obscured because planned shipbuilding numbers are good. The new Dreadnought class deterrent submarines are in train as are the last of the Astute class attack submarines. The collaboration with the US and Australia for the next generation of attack submarines remains sound, although that is a long way away and many hurdles remain. The Type 26 and 31 Frigates are (finally) progressing nicely and the news that they will both have Mark 41 vertical launchers, able to carry effective American missiles of all kinds, is welcome.

The fact that, to my mind, takes a little bit of the gold leaf off ‘the golden age of shipbuilding’ here in the UK is the number of ships that are being asked to run on beyond their programmed lifespan because these projects all started too late. Resource constraints make getting programs across the line so difficult that we are now seemingly incapable of starting a complex build programme in time for it to be finished as the previous class pays off. Delays in build due to politics, shipyard capacity issues and design tinkering all compound this. Capability gaps are now the norm, sometimes huge ones.

The venerable Type 23 frigates typify this. They were built in the 1990s and Noughties and were designed to run reasonably low-intensity towed array patrols in the North Atlantic with a life span of 18 to 20 years. Even the very newest (and best) one, my old command HMS St Albans – just coming out of an extended maintenance period – is already 24 years old. They will all be in their late 30s by the time the T26s are ready to relieve them.

Running ships on past their designed life like this creates two problems. First is the cost of keeping them mechanically sound and safe to operate. The refits cost more than it cost to build them. Second, you are forced to throw money at what in technological terms is now an ‘old ship’. The latest advancements in weapons, sensors, AI, communications and satellite networks – all the things we are working so hard to develop to retain a technological edge – become increasingly incompatible with the ageing platforms.

The USN's futuristic Zumwalt class destroyer has not been a success. Only three will ever join the fleet - US Navy/Getty

Older ships also use more people, the reason I am confident we won’t see our two Royal Navy amphibious assault ships on operations anytime soon, despite the announcement that they will not be paid off early.

It’s doubly frustrating that we are in the middle of making the same mistake again with the replacement for the Type 45 destroyers. HMS Daring, first of class, was launched in 2006 and should therefore be expecting to retire in 2036 at the latest. If the Type 45 replacement is to be ready in time, designs need to be mature now and contracts awarded straight away.

To give an idea, steel was first cut on the Type 26 Frigate in July 2017 but that ship won’t reach initial operating capability until October 2028. But that was on the back of a further seven years of contract discussions and awards, i.e. it took 18 years from ‘concept’ to ‘operational’.

Meanwhile, over in the US, the Zumwalt class was a case study of what happens if you try to pack too much new and untested technology into one hull. The initial plan was to build 32 but as the costs skyrocketed, this reduced to 24, then to seven. The USN has ended up with three. A related case was the Seawolf submarines, which are powerful but horrendously costly. Again, the USN only got three, though in this case the more reasonably priced Virginia class successor project has been a great success.

With surface ships the USN did not recover as well – if at all. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) is perhaps the exemplar of a programme that started with a confused concept of operations, was rushed into production, and got worse from there. It took about 12 years from launch before they were universally being referred to as ‘little crappy ships’. Needless to say, the US Navy hasn’t let the almost unarmed LCSs anywhere near the current littoral combat theatre in the Southern Red Sea.

And now the Constellation class frigate, the US answer to our Type 26, is also in a bit of a mess. On this occasion, the USN took the excellent and proven Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM) design and rather than modifying 15 per cent of it for US purposes as initially stated, modified 85 per cent. It’s basically a new ship. A combination of this meddling and workforce shortfalls in the yard where it is being built have caused delays and a price hike.

So ‘too expensive’, ‘unreliable’ and ‘fiddled with too much’ in sequential order. It’s almost as though the USN can’t build new surface combatant warships at all any more. Fortunately, in the long running Arleigh Burke destroyer programme, the US not only produced one of the best warships ever at the start, it is also one of the most modifiable. The latest ones, still coming off the line, physically resemble their forebears of 33 years ago but that’s about it: and the old ones still in service have been upgraded in line with the new ones.

Arleigh Burke class. When you get something right, keep doing it - MC3 Lasheba James/US Navy/AFP/Getty

Here in Britain our replacement air defence destroyer, the Type 83, will need to avoid all these traps. It will need to be advanced (but not too much), have what is meant to be inked in from the start and then not be tinkered with during build.

That’s not going to be easy, however. The things an air defence destroyer needs to be able to do are expanding and shifting at pace. The Future Air Dominance System (FADS) is the collective term for this and whilst accelerating fast, the concept is still in its infancy.

Whatever FADS ends up being, it will need to be advanced but not too expensive. It must be survivable and not have too many people onboard. It must carry lots of (reloadable at sea) missiles but not be too big and expensive. It will need to counter swarm attacks by cheap and simple drones or missiles (the forthcoming Dragonfire laser should be useful here). It will also need to shoot down ballistic missiles in space, supersonic or hypersonic missiles from the upper atmosphere to sea level, and defend against surface attack (also drones). It should be able to knock down targets below the horizon which are being tracked by something else such as an airborne radar aircraft.

The Red Sea has confirmed beyond doubt that warships need to be able to strike targets ashore – add this to the list, though most navies apart from the Royal Navy had already done so. The Type 83s will need to be able to conduct disaggregated operations thousands of miles from other ships but also in a task group next to the carrier (this is a key requirement).

These are complex and sometimes conflicting requirements to the point where some FADS concepts dispense with the idea of a large ship at all, relying instead on a fleet of smaller arsenal and uncrewed ships. This could work in wartime, and might even save money (never far away in the conversation) but solutions like this often overlook the 99 per cent of the time when a warship’s job is to prevent the war in the first place.

So, to my mind, peacetime operations, deterrence work, radar physics and probably a pinch of traditionalism means that FADS will still have a destroyer-looking ship at its core with the option to add remotely operated or heavily armed options down the line. It won’t be a vast cruiser (see Zumwalt) or small and under-armed (see the LCS).

But FADS needs to mature now because the equation is simple: no destroyers = no carriers = no conventional deterrent in far too much of the world. And if they’re not ready in time, we know from the Type 23s what it costs to run ships beyond their expected life and given the complexities (and difficulties) of the Type 45 power train, it will be worse if we have to do it again.

So I would question the notion that we are in a golden age of shipbuilding here in the UK. If we have entered a golden anything it should be the age of budget holders finally recognising how tight things have become in the Royal Navy, how this could compromise the defence of the nation in the face of increasing threats and the demands this continually places on the service’s excellent people.

In the States the problems are less ones of lacking money and vision – the US has long had clear ideas on a powerful navy and has provided ample funds. Problems in America are ones of execution, with at least three major ship classes failing to reach service in any numbers over the last three decades – leaving the USN, like the RN, with a lot of the same ships it had 30 years ago.

The good news is that in both nations the desire is there to meet the threats of the future. The two navies now just need to be given the resources and freedom to deliver. In the specific case of the Type 83 destroyer, that time for decisive action is now.

Tom Sharpe is a former Royal Navy officer and surface combatant captain

No comments:

Post a Comment