CBC

Thu, May 23, 2024

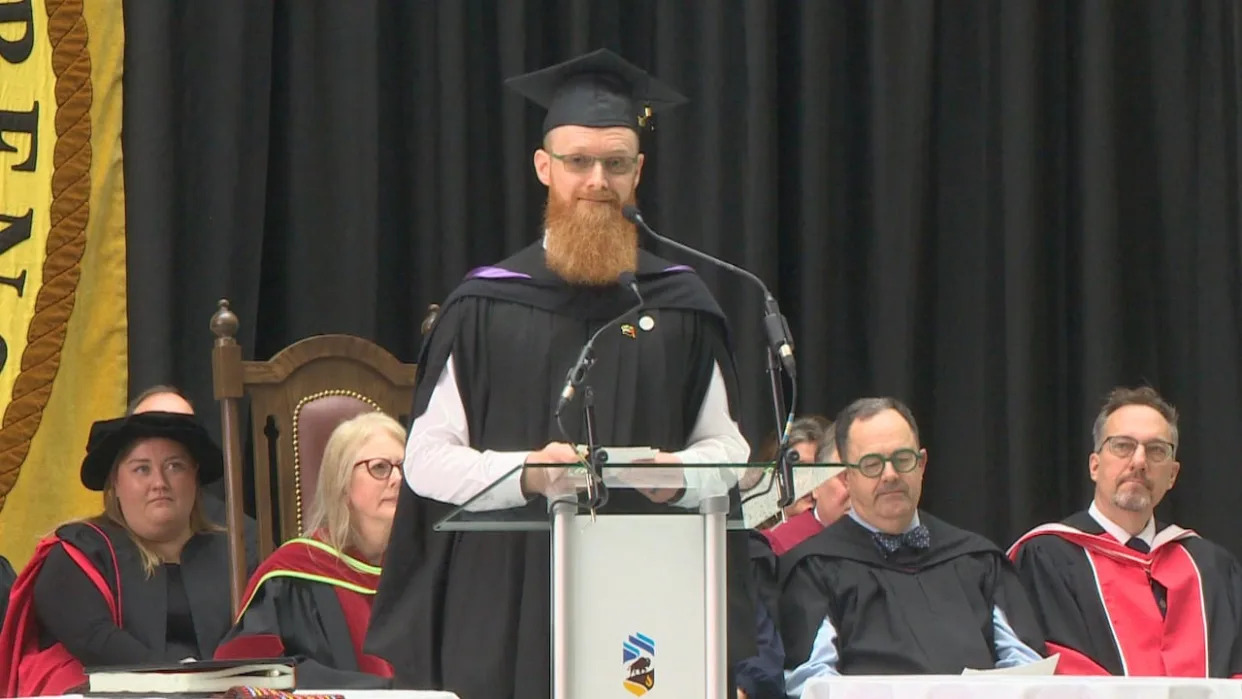

Dr. Gem Newman is pictured during his valedictory address at the May 16 convocation for students from the Max Rady College of Medicine.

(Radio-Canada - image credit)

A speech to a graduating class of doctors that led to tension between the University of Manitoba's medical school and the person behind the university's largest-ever private donation has sparked debate about how much influence donors should have over the institutions.

In his valedictory address at the May 16 convocation for students from the U of M's Max Rady College of Medicine, Dr. Gem Newman told fellow graduates to demand a ceasefire in Gaza and called out medical associations for "deafening silence" on the humanitarian crisis there.

Ernest Rady — a U of M grad and businessman whose $30 million donation led to the medical school being named for his father — wrote a letter to the university denouncing the speech as "hateful" and disparaging of Jewish people, and demanding the university take down a video that included the speech.

Doug White, an American philanthropy adviser who has written about the non-profit sector, says both the valedictorian and the donor have the right to express their views.

"Now, the donor and others could be very upset, but to demand that the university take down the video, I feel like that's not productive," he told CBC on Wednesday.

"I don't think it should have been taken down, period."

College of medicine dean Dr. Peter Nickerson, who called Newman's remarks "divisive and inflammatory," confirmed to CBC Wednesday that the video that included the speech was taken down, saying Rady was "far from the first person" to ask for that.

A speech to a graduating class of doctors that led to tension between the University of Manitoba's medical school and the person behind the university's largest-ever private donation has sparked debate about how much influence donors should have over the institutions.

In his valedictory address at the May 16 convocation for students from the U of M's Max Rady College of Medicine, Dr. Gem Newman told fellow graduates to demand a ceasefire in Gaza and called out medical associations for "deafening silence" on the humanitarian crisis there.

Ernest Rady — a U of M grad and businessman whose $30 million donation led to the medical school being named for his father — wrote a letter to the university denouncing the speech as "hateful" and disparaging of Jewish people, and demanding the university take down a video that included the speech.

Doug White, an American philanthropy adviser who has written about the non-profit sector, says both the valedictorian and the donor have the right to express their views.

"Now, the donor and others could be very upset, but to demand that the university take down the video, I feel like that's not productive," he told CBC on Wednesday.

"I don't think it should have been taken down, period."

College of medicine dean Dr. Peter Nickerson, who called Newman's remarks "divisive and inflammatory," confirmed to CBC Wednesday that the video that included the speech was taken down, saying Rady was "far from the first person" to ask for that.

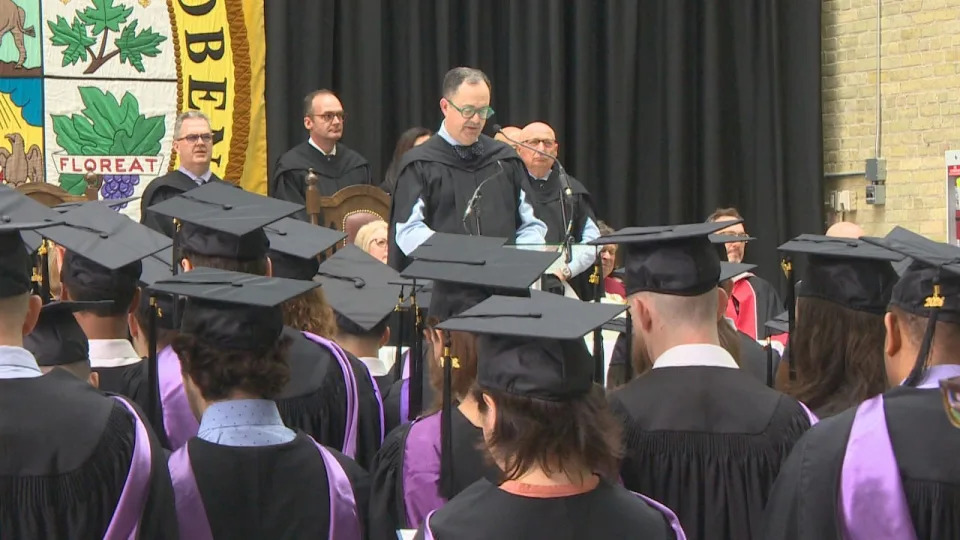

Dr. Peter Nickerson, dean of the University of Manitoba's Max Rady College of Medicine, is seen reciting the physician's pledge for graduates at their May 16 convocation.

Dr. Peter Nickerson, dean of the University of Manitoba's Max Rady College of Medicine, is seen reciting the physician's pledge for graduates at the May 16 convocation. He says Rady was 'far from the first person' to ask for video of Newman's speech to be taken down. (Radio-Canada)

The school's website includes a "donor bill of rights," which says U of M benefactors are entitled to know what their contributions are being used for and can "expect that all relationships with individuals representing organizations of interest to the donor will be professional in nature."

The question becomes whether Rady's opinion should hold any influence over how the University of Manitoba operates, White said.

"It sounds like this is an opportunity for universities to re-examine their missions and … their communications with their donors."

He says as valedictorian, Newman was asked to make a speech and had the right to share his opinion.

"If [the university] doesn't otherwise vet a valedictorian's speech, it shouldn't be done now."

Students should be raising questions: prof

The ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict, which began after an Oct. 7 cross-border attack on Israel led by Hamas, killed roughly 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and took 250 others hostage.

Israel launched an offensive in response that has killed more than 35,000 Palestinians, according to the latest estimates by Gaza health officials. The Israeli military operation has also triggered a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, displacing roughly 80 per cent of the population and leaving hundreds of thousands of people on the brink of starvation, according to UN officials.

The conflict has also led to numerous protests on school campuses across the globe, including at the universities of Manitoba and Winnipeg.

Roberta Lexier, an associate professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary whose research focuses on social movements, protest and academia, says it's not unusual to see political statements at graduation, but they don't often make it into valedictory speeches.

University administrators have been concerned about the prospect of pro-Palestinian protests bleeding into graduation season, but "I think they shouldn't be," said Lexier.

"I think this shows their students are learning what they're supposed to be learning about — challenging … and questioning the world that they live in."

The University of Manitoba Rady Faculty of Health Sciences has received more than $735,000 to help 400 - 500 foreign trained health professionals find work in their fields.

A video on the University of Manitoba's YouTube channel that included a medical graduate's valedictory speech last week has since been taken down after criticism of the valedictorian's call for a ceasefire in Gaza. (Bryce Hoye/CBC)

Lexier says while universities are embedded into society, they are also "purposefully meant to be somewhat separate" so academics can question societal structures.

"I think we get into a different conversation when we're talking about professional schools, like medicine and others, but I think what's really important is that universities need to allow their students, their faculty, their staff and others to participate in these discussions."

She says people need to accept that Canadians have the right to freedom of expression, so long as they do not veer into hate speech.

"We have the right to say what we want to say, whether people like that or not, and the idea of an institution, especially a university, censoring somebody's speech … seems incredibly inappropriate."

'Tension' between donors, universities: CAUT president

Peter McInnis, president of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, says private donors make positive contributions but have grown increasingly important as universities face more public funding cuts, and there's "always a tension" in that relationship.

"Universities and colleges [have to be] very mindful that they don't accept money with too many strings attached," he said.

"You can get into some really deep waters at times, but I think that as long as the lines are clear, these controversies can be dealt with in a reasonable way."

While tensions are high right now, universities are supposed to be a forum for difficult discussions, said McInnis.

"We're usually better [off] if we allow them to take place, rather than attempting to suppress them."

Opinion: If you opposed the pro-Palestinian protests, here’s why you should reconsider

Opinion by Haroon Moghul

Fri, May 24, 2024

Editor’s Note: Haroon Moghul is director of Strategy at The Concordia Forum and the author of ”Two Billion Caliphs: A Vision of a Muslim Future.” His Substack, ”Sunday Schooled,” provides resources and curricula for Muslim parents, teachers and leaders. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

When I was growing up, most of my South Asian friends and peers were pushed into medical careers. I was able to go in a different direction, initially attending law school, only to realize early in my first semester that a legal career wasn’t what I wanted.

Haroon Moghul - Courtesy Haroon Moghul

Coming from a literary and scholarly Pakistani-American family, I yearned to learn more about my faith. I wanted to challenge misperceptions about Islam. I wanted to teach and empower.

A year after graduating from college, I enrolled at Columbia University’s Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies, eager to study with the many scholars who approached Islam on its own terms, with respect, rigor, nuance and a love of inquiry.

In the nearly decade and a half since I graduated with a master’s degree, I’ve continued to draw on the remarkable education I received. That has included designing historical experiences immersing travelers in the Muslim legacy in Europe: A new kind of Sunday school for middle and high schoolers. And global leadership programs for young Muslim professionals from across the West, strongly influenced by the kind of creative and open-ended inquiry I often experienced at Columbia. That is why I found what transpired at Columbia University these last few months so profoundly disappointing.

The weeks of student protests (which continue at some campuses) should provoke us to reflect on the larger impact of this movement — especially at my alma mater, where the main commencement ceremony, which had been scheduled for this week, was canceled. (Protesters and their supporters organized their own ceremony.)

The media line fed to the public about weeks of protests at Columbia — and the administrative crackdown that followed — has been selective at best. I know this as an alumnus, a parent with two kids on the verge of college and as someone who teaches young Americans, including high schoolers. I know adolescents and young adults are far more passionate, curious, creative and courageous than older adults sometimes casually assume.

America’s universities are the envy of the world and are meant to be laboratories for democracy and engines of innovation, keeping our society democratic and vigorous, economically dynamic and forward-facing. But instead, it appears too many this spring have seemed intent on suffocating debate they don’t endorse, rather than promoting and protecting the exchange of ideas.

I’m incensed by the same realities the student protesters are outraged by: Israel’s occupation and brutalization of Palestinians with our country’s active assistance. Columbia students have made clear that that’s what drives their protests. What’s less widely reported is how they are also driven by double standards in how our leaders address Israeli and Palestinian issues.

When was the last time you heard a news report about anti-Arab or anti-Muslim animus on campuses? Where is the outcry for the pro-Palestinian students threatened with professional consequences only for protesting? Why, even as numerous students at Columbia and elsewhere have been doxxed, harassed and bullied, were no congressional hearings called?

Long before our protracted national conversation about antisemitism got underway, some Columbia faculty members have quite arguably crossed a line into anti-Palestinian agitation, with no apparent consequences. And at UCLA, pro-Israel demonstrators even attacked pro-Palestinian student encampments for hours. Police were nowhere to be seen.

For months now, we’ve seen pro-Palestinian students, including Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims, as well as students of other backgrounds and faiths (including many Jewish students), held to different standards and demonized when they are in fact standing up for fundamental human, basic American and common civic values. There may be no better symbol of this than Columbia’s President Minouche Shafik, who last week was on the losing end of a no-confidence vote by faculty over her handling of the protests.

When Shafik was called to testify before a biased congressional hearing, she faced a hard choice. Two of her fellow Ivy League president predecessors did not hold onto their jobs very long after appearing before the same House panel, some of whose members seemed gleeful at the prospect of taking down another.

In my view, Shafik capitulated. She told Republican lawmakers everything that they appeared to want to hear. But she did not have to capitulate. She could have questioned the dubious, even dangerous assumptions inherent in the questions themselves. She could have taken a stand on principle, in support of students expressing their views in the best tradition of campus protest. She might have considered the blatant double standards at her and peer institutions.

She might have told lawmakers that all speech is free, or none is. She might have invited our national leaders to engage in a more difficult conversation — one which would have been less sensationalistic than the congressional hearing they held, but probably far more substantial.

Such a dialogue could have addressed how we balance free inquiry in a country of robust pluralism. It might also have raised the question about what it means to balance strong beliefs, academic rigor and mutual respect.

That’s the kind of engagement we sorely need more of in this country. It’s the kind of discussion a university president such as Shafik would have been uniquely positioned to lead. She capitulated to bad-faith interrogators after the collapse of days of talks, then invited heavily armed police onto campus. Somehow, she and other authorities seemed more concerned with the purported unruliness of the protest than the horrors that prompted it.

Palestinians in this country, as well as pro-Palestinian demonstrators, have been shot at, menaced, struck with vehicles, merely for who they are or what they stand for. But there has been no congressional hearing about these crimes and hardly even acknowledgement in many quarters that these crimes have happened. That Shafik even had to appear before Congress is just another example of how deeply entrenched our double standards are.

Students aren’t out of touch with America. A majority of Americans disapprove of Israeli actions in Gaza. Student protesters are confirming what more and more Americans cannot deny, even while many of our elites remain seemingly indifferent. We might on reflection appreciate that it is better to see young Americans exceedingly committed to freedom, debate and challenging our hypocrisies than not.

That hardly means we are all going to agree on how to protest or on what approach is better — but we should all agree on the right to protest — and the responsibility of the protesters to push our country to do better.

Just a few weeks ago, I joined some 50 or so American Muslims and allies in Washington, DC, leaders and activists from diverse backgrounds, coming together to explore what it might mean to continue to advocate for our faith communities. That included continuing to hold our government to account for our role in Israel’s war and protecting freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

There was a special level of interest in protecting our universities from governmental and elite interference, preserving the unique space campuses provide for hard conversations, political exploration and civic formation. Most of us were deeply disappointed by how our respective alma maters put select donors over institutional integrity. But the energy and engagement underscored the commitment to this cause.

We left inspired to continue standing up for the right to protest and leverage our resources to put pressure on these colleges and universities to maintain academic freedom, to uphold standards that do not privilege certain politics or positions and to maintain and extend the opportunities our colleges had opened for us — a commitment I believe continues down to this present momentWhen Shafik arrived at those hearings, she faced some lawmakers who acted as if they believed universities, and those on campus who are allies of the Palestinians, were enemies of America.

But if Columbia students didn’t care about their university and the values it claims to uphold, they wouldn’t have risked so much with their protests. By the same token, if students didn’t care about our country, they wouldn’t protest so vocally against its policies.

Maybe these students are mirrors of America, revealing how much work we have left to do. But they also reveal that there is enough passion, commitment and courage that our causes are not lost. Our struggles are not pointless. A better future can be ours.

No comments:

Post a Comment