A DANGEROUS MENAGE A TROIS

The Triangular Relationship between Iran, Israel and the US: An Ongoing CrisisMarianna Charountaki

May 9th, 2024

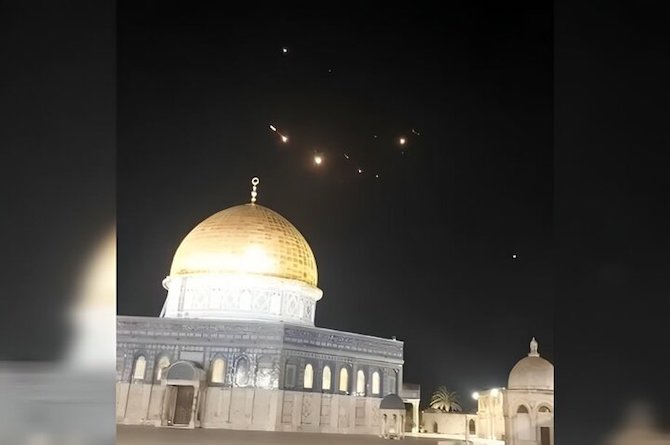

ranian drones flying over the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, 13 April 2024.

Source: Mehr News

The 2011 crisis in Syria facilitated an era of international non-polarity and signalled the revival of the Middle East’s regional powers, among which Turkey and Iran have particular prominence. In this context, the Palestinian cause has, once more, become a pretext for the actors involved to take steps to get the upper hand and project power. The assault on Gaza has rejuvenated regional conflicts, most significantly the Palestinian issue, giving fresh impetus to the need for a resolution. For the first time since 2010, Iranian foreign policy and its role in the regional order is front and centre, giving international opponents to Iran an opportunity to rally.

Despite major regional tensions that had been on the verge of escalating into a direct military confrontation, such as those between Iran and Saudi Arabia since 2016, who had cut off official ties until April 2021 (Aljazeera, 2023), it is only very recently that Iran has been confronted militarily by Israel. Such direct attacks against Iran, as was the case with the 1 April 2024 Israeli strike on the Iranian consulate in Damascus and most recently on an Iranian airfield in Isfahan – the cradle of Iran’s nuclear programme – are important developments which should not be underestimated. The fact that Israel pushed Iran to respond alone constitutes an interim success, though all sides involved currently appear hesitant to pursue this path further given the number of unknown factors concerning conflict escalation. The US, for instance, has revived its discourse about the threat to regional stability posed by Iran’s policy of ‘destruction throughout the region’ (Kurda, 2024). At the same time though, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s call for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to resign in addition to Democratic lawmakers urging the halt of US weapons provision to Israel (Singh, 2024) stand in stark contrast to the US foreign policy agenda to curb Iranian influence in the region, dating back to the George W. Bush era (2001–9). The Israelis’ challenge vis-à-vis Iran’s foreign policy showed that they are the only player adjusting the power balance in the wake of a new and unexpected Iranian policy shift.

Iran’s long-term strategy to divert international attention from internal issues, in view of the debate over its nuclear capabilities and the wider turmoil engulfing the region, demonstrate why a focus on instability or changes in the regional status quo strengthens Tehran’s agenda (Charountaki, 2018: 14). A closer observation of Iran’s revolutionary foreign policy indicates that its focus on instigating instability has remained consistent. Iran’s foreign policy is based ‘on a strategic approach against US hegemony’ (Ibid: 16). Concurrently, the US has perpetuated its dual-track policy of reset and withdrawal, consolidated since the Obama era, but now its foreign policy is represented by Biden’s five C’s (consult, convene, compartmentalise, calm, compete). The latter is focused on ‘rehabilitating America’s reputation as a champion’ (Grunstein, 2021) in line with the traditional US foreign policy discourse that aimed at ‘the nation’s international prestige as a world leader’ (Reagan, 1988: 4). Such a task in the current unpredictable world order necessitates the reconsideration of traditional US foreign policy practices in the Middle East.

Along similar lines, Israel’s challenge to Iranian foreign policy constitutes an attempt to rebuild its prestige following the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War, as well as Hamas’ more recent miscalculation of the time and possibly severity of the response its action itself against Israel. The mechanisms of the state Leviathan, epitomised by the current conflict, are now mobilised in the name of self-defence and ‘limited’ attacks (Amir-Abdollahian, 2024) vis-à-vis Iran’s assurances about its reluctance to continue acts of warfare as its only means of survival. Indeed, the recent meetings between Tehran and the Kurdistan Region in Iraq (Tehran Times, 2024) seeking to develop cooperative relations in the context of a good neighbourhood policy is a case in point. Thus, developments in this conflict should not be understood merely as an Iranian-Israeli confrontation, but as part of the international and regional containment of Iran. Whether containment remains at the forefront of international players’ foreign policy agendas will determine any future concrete shifts in Iran’s own foreign policy towards international legitimacy.

At present, the Gaza conflict is taking its intended shape as the fighting is now between the actors at the heart of the conflict: Iran and Israel. Thus, the central question of this conflict (that has changed from an indirect to a dynamic one) is whether it can facilitate the transition from a state’s mere survival, according to the realist tradition, within a hostile environment, to a state’s pragmatic functioning – a shift that can only be evaluated at the political level.

The 2011 crisis in Syria facilitated an era of international non-polarity and signalled the revival of the Middle East’s regional powers, among which Turkey and Iran have particular prominence. In this context, the Palestinian cause has, once more, become a pretext for the actors involved to take steps to get the upper hand and project power. The assault on Gaza has rejuvenated regional conflicts, most significantly the Palestinian issue, giving fresh impetus to the need for a resolution. For the first time since 2010, Iranian foreign policy and its role in the regional order is front and centre, giving international opponents to Iran an opportunity to rally.

Despite major regional tensions that had been on the verge of escalating into a direct military confrontation, such as those between Iran and Saudi Arabia since 2016, who had cut off official ties until April 2021 (Aljazeera, 2023), it is only very recently that Iran has been confronted militarily by Israel. Such direct attacks against Iran, as was the case with the 1 April 2024 Israeli strike on the Iranian consulate in Damascus and most recently on an Iranian airfield in Isfahan – the cradle of Iran’s nuclear programme – are important developments which should not be underestimated. The fact that Israel pushed Iran to respond alone constitutes an interim success, though all sides involved currently appear hesitant to pursue this path further given the number of unknown factors concerning conflict escalation. The US, for instance, has revived its discourse about the threat to regional stability posed by Iran’s policy of ‘destruction throughout the region’ (Kurda, 2024). At the same time though, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s call for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to resign in addition to Democratic lawmakers urging the halt of US weapons provision to Israel (Singh, 2024) stand in stark contrast to the US foreign policy agenda to curb Iranian influence in the region, dating back to the George W. Bush era (2001–9). The Israelis’ challenge vis-à-vis Iran’s foreign policy showed that they are the only player adjusting the power balance in the wake of a new and unexpected Iranian policy shift.

Iran’s long-term strategy to divert international attention from internal issues, in view of the debate over its nuclear capabilities and the wider turmoil engulfing the region, demonstrate why a focus on instability or changes in the regional status quo strengthens Tehran’s agenda (Charountaki, 2018: 14). A closer observation of Iran’s revolutionary foreign policy indicates that its focus on instigating instability has remained consistent. Iran’s foreign policy is based ‘on a strategic approach against US hegemony’ (Ibid: 16). Concurrently, the US has perpetuated its dual-track policy of reset and withdrawal, consolidated since the Obama era, but now its foreign policy is represented by Biden’s five C’s (consult, convene, compartmentalise, calm, compete). The latter is focused on ‘rehabilitating America’s reputation as a champion’ (Grunstein, 2021) in line with the traditional US foreign policy discourse that aimed at ‘the nation’s international prestige as a world leader’ (Reagan, 1988: 4). Such a task in the current unpredictable world order necessitates the reconsideration of traditional US foreign policy practices in the Middle East.

Along similar lines, Israel’s challenge to Iranian foreign policy constitutes an attempt to rebuild its prestige following the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War, as well as Hamas’ more recent miscalculation of the time and possibly severity of the response its action itself against Israel. The mechanisms of the state Leviathan, epitomised by the current conflict, are now mobilised in the name of self-defence and ‘limited’ attacks (Amir-Abdollahian, 2024) vis-à-vis Iran’s assurances about its reluctance to continue acts of warfare as its only means of survival. Indeed, the recent meetings between Tehran and the Kurdistan Region in Iraq (Tehran Times, 2024) seeking to develop cooperative relations in the context of a good neighbourhood policy is a case in point. Thus, developments in this conflict should not be understood merely as an Iranian-Israeli confrontation, but as part of the international and regional containment of Iran. Whether containment remains at the forefront of international players’ foreign policy agendas will determine any future concrete shifts in Iran’s own foreign policy towards international legitimacy.

At present, the Gaza conflict is taking its intended shape as the fighting is now between the actors at the heart of the conflict: Iran and Israel. Thus, the central question of this conflict (that has changed from an indirect to a dynamic one) is whether it can facilitate the transition from a state’s mere survival, according to the realist tradition, within a hostile environment, to a state’s pragmatic functioning – a shift that can only be evaluated at the political level.

About the author

Marianna Charountaki is Senior Lecturer in International Politics at the University of Lincoln and a Research Fellow at Soran University (Erbil, KRI). She is the author of The Kurds and US Foreign Policy: International Relations in the Middle East since 1945 (Routledge, 2011) and Iran and Turkey: International and Regional Engagement in the Middle East (I.B. Tauris, 2018) and is the co-editor of Mapping Non-State Actors in International Relations (Springer, February 2022).

No comments:

Post a Comment