Associated Press

Mon, June 10, 2024

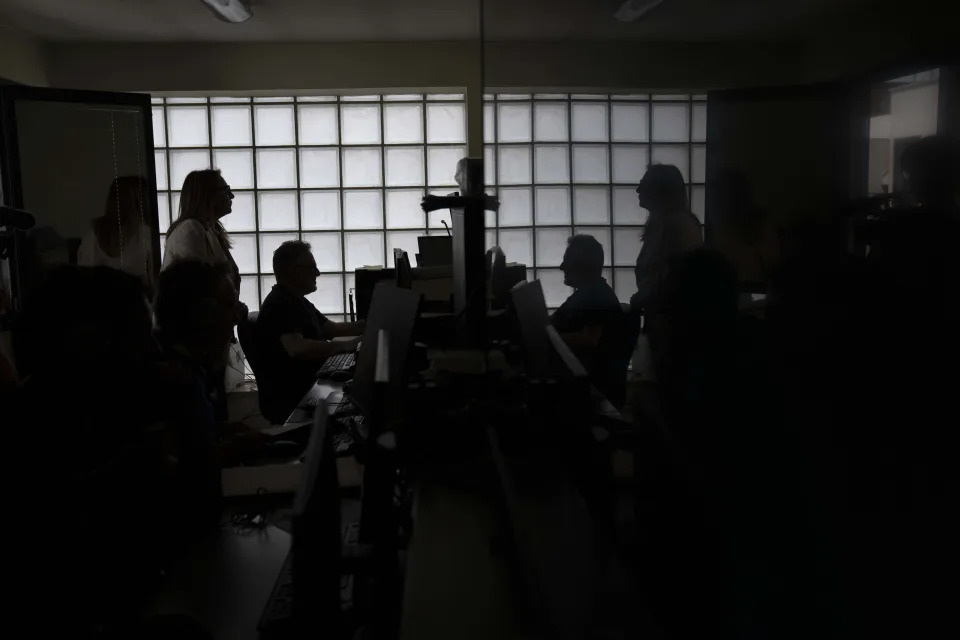

A view of the bunker hall of Lecce, Italy, before the start of an audience, Wednesday, May 22, 2024. In the past few months, Carmen Ruggiero, the prosecutor leading the team against a clan in a case known as "Operation Wol." was threatened by a jailed mafioso.

ROME (AP) — Last month, an Italian administrative court confirmed the dissolution of the city administration of the Puglia city of Neviano, after an investigation determined that local officials were being unduly influenced by the mafia.

The decision barely made news in Italy, where city hall administrations, town councils and local public health agencies are regularly dissolved because of mafia infiltration or collusion, and independent commissioners appointed to take over.

While the popular image of the Italian mob was made famous by Don Corleone and the gangland shootouts of “The Godfather,” the reality of organized crime in Italy today is far more nuanced and eats away at the heart of its democracy: local governance.

From the awarding of big public works contracts to small-town decisions about who manages landfills, parking lots and beach concessions, local governments are particularly vulnerable to mafia influence and corruption, according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, an interagency organization.

Puglia, which will host this week’s Group of Seven summit, ranks fourth among Italian regions in the number of local administrations that have been dissolved because of mafia infiltration, with 26 decrees issued since 1991, out of a national total of 326, according to Avviso Pubblico, an Italian association that tracks the decrees.

That fourth-place ranking also corresponds to the fourth-place status of its local mafia, the Sacra Corona Unita, on the hierarchy of Italy's mafia clans.

The SCU is the youngest and smallest of the organized crime groups in the country, after the ‘ndrangheta in Calabria, the Camorra in Campania and Cosa Nostra in Sicily. And it is the only one whose origins are really known: it was founded in prison in the early 1980s by Pino Rogoli as an autonomous Puglia-based alternative to other mobs.

While initially focusing on the trafficking of cigarettes and other contraband with Balkan countries, the SCU’s clan-based organization morphed into drug trafficking and extortion.

In the 2000s, it began a new phase “of getting rooted in the territory, the so-called cover-up and camouflage phase," said Marilù Mastrogiovanni, an investigative journalist and journalism professor at the University of Bari.

That phase, which is bearing fruits for clans today, involved avoiding calamitous acts of violence "so that everyone, from ordinary citizens to law enforcement, would forget about it,” she said.

Now, the focus is on laundering drug profits through legitimate front companies, many catering to Puglia’s booming tourism industry, while infiltrating the local public administration to steer public contracts its way, said Carla Durante, head of the Lecce office of Italy’s Anti-Mafia Investigative Directorate.

Europol, the European police force, says 60% of the organized crime groups it tracks in Europe engage in some sort of corruption, from petty bribery of public officials to multi-million euro corruption schemes.

“Corruption erodes the rule of law, weakens institutions of states and hinders economic development,” Europol said in its latest report, “Serious and Organized Crime Threat Assessment.”

___

This story, supported by the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, is part of an ongoing Associated Press series covering threats to democracy in Europe.

Associated Press

Mon, June 10, 2024

Italy G7 Mafia Biographies

Marilu Mastrogiovanni poses in front of a murales dedicated to Gloria Anzaldua, an American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory, during an interview at the Bari's university, Monday, May 20, 2024. Investigative journalist, Professor of Investigative Journalism, has reported extensively on the infiltration of the Sacra Corona Unita in the local community and city hall for her blog "Tacco d'Italia." Her reports so angered the local government that they plastered the town with giant posters attacking her work and one depicted her up to her neck in a hole in the ground. After various threats, she was put under police escort and eventually decided to move her family to Bari where she now teaches investigative journalism in the Master in Journalism course at the University of Bari.

A remarkable group of women is challenging the power structures of the Sacra Corona Unita, Italy’s fourth main organized crime group that operates in southern Puglia, the heel of Italy’s boot.

They are doing it at great personal risk, arresting and prosecuting clan members, exposing their crimes and confiscating their businesses, all while working to change local attitudes.

Here is a look at some of these women:

Carla Durante

Durante heads of the Lecce office of the Direzione Investigativa Anti-Mafia, Italy’s inter-agency anti-mafia police force, but her rise in the ranks was met with obstacles from the start.

When she told her high school Latin teacher that she wanted to become a police officer, the response was typical of the macho ethos of southern Italy at the time: “How vulgar.”

The reception wasn’t much better in Durante’s first job, as a cop in a small mountain town in southern Calabria that was dominated by the ’ndrangheta mafia. The locals in Taurianova were hostile to all law enforcement officers and were not afraid to show it.

For example?

“When they torched my car,” she says matter-of-factly.

Now back home, Durante is battling the local Sacra Corona Unita mafia, and hitting its leaders where it hurts most: confiscating their ostentatious properties, farms and front companies used to launder drug trafficking profits.

“We have learned that this is really the most incisive tool, because taking assets away from mafiosi means disempowering them,” she says.

___

Marilù Mastrogiovanni

Mastrogiovanni is an investigative journalist and journalism professor at the University of Bari. She has reported extensively on the infiltration of the Sacra Corona Unita mafia in local Puglia communities and public administrations for her blog “Il Tacco d’Italia.”

Her reports so angered the local government in her hometown that at one point, the town was plastered with giant posters attacking her work, one of them depicting her up to her neck in a hole. After various threats, she was put under police escort and eventually decided to move her family out of town.

According to the patriarchal culture of the Sacra Corona Unita, “a woman shouldn’t have a voice,” all the more if she uses it to write about the mafia, she said.

Is she afraid?

“I don’t believe those who say they aren’t afraid. It is not true,” she says. “Courage is going forward in spite of fear.”

___

Rosanna Picoco

Picoco volunteers for the anti-mafia group Libera, activism that was inspired by a childhood event.

When she was in elementary school near Lecce, three bombs exploded in her school one night. Local store owners had created the first anti-racketing association in town, refusing to pay off local mobsters, and the bombs were a clear warning from the Sacra Corona Unita that their children were at risk.

But instead of backing down, the parents did something remarkable that stayed with Picoco forever.

“The next morning our parents — all of them — accompanied us to school,” she recalls. “In the whole town, no one remained silent, and I think this has always marked me: The importance of not turning away, of being on the side of being active citizens.”

Picoco now volunteers with Libera, a national network of anti-mafia associations that, among other things, takes legal possession of confiscated mafia assets and turns them into socially useful projects and products.

At a Libera store in Mesagne, the Puglia town where the Sacra Corona Unita was founded, Picoco sells wine made from grapes grown in vineyards confiscated from the mafia. The bottles bear the names of mafia victims.

___

Maria Francesca Mariano

Mariano is the preliminary investigations judge at the Tribunal of Lecce. At the age of 24, she became the youngest woman judge in Italy. Now 55, she lives under a 24-hour police escort.

In July 2023, she issued arrest warrants for 22 members of the Lamendola clan of the Sacra Corona Unita organized crime group, on accusations of mafia association, drug trafficking and other charges.

Then, in October, she began receiving letters written in blood with death threats and satanic messages. On Feb. 1, a bloody goat head skewered with a butcher’s knife was left on her doorstep with a note reading, “like this.”

Police added a bullet-proof car to her security apparatus.

She still has her day job as a judge but in her down time, Mariano writes books, plays and poetry about the mafia in Puglia.

“The mafia has social consensus,” she says. “If we want to disassociate the phenomenon of organized crime, it is not enough to work in a courtroom. We have to start with the people.”

___

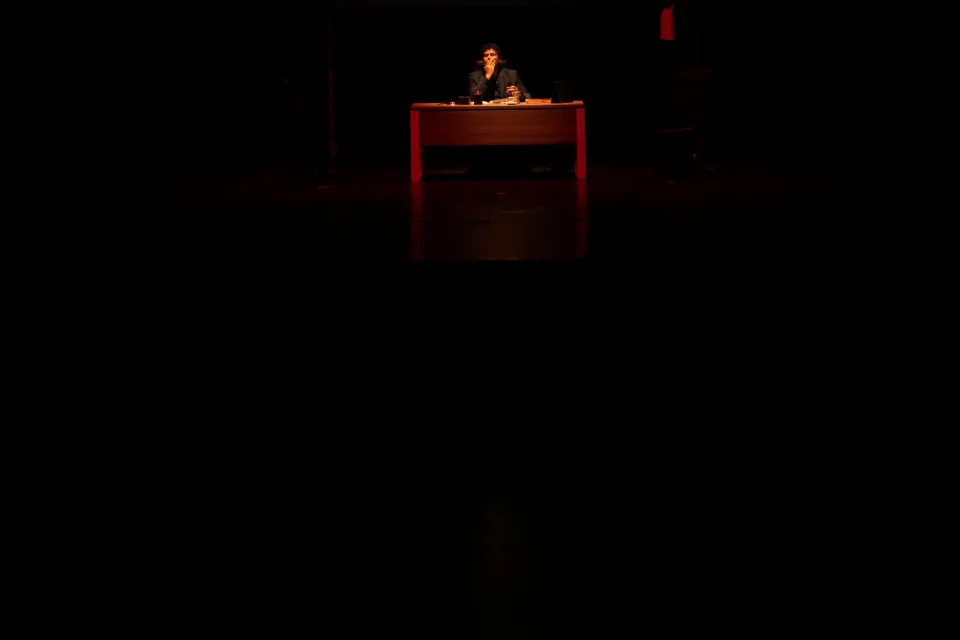

Carmen Ruggiero

Ruggiero is a Lecce prosecutor. She leads a prosecution team in the case of “Operation Wolf” against the 22 defendants from the Lamendola clan of the Sacra Corona Unita.

She has not relented in her efforts following threats on her life but now appears in the Lecce prison courtroom accompanied by a three-man police escort.

Shortly after Judge Mariano sent out her arrest warrants, Ruggiero went to the Lecce prison to question one of the defendants who had signaled his desire to collaborate.

Instead, Pancrazio Carrino had chiseled a knife out of a porcelain toilet bowl in his prison cell and hid it in a small black plastic bag in his rectum, planning to “cut her jugular” during the meeting, according to court documents following the incident.

Carrino told investigators he had asked to use the bathroom so he could retrieve the makeshift knife and hide it in his underwear until he could strike. But a suspicious police officer searched him when he came out and took it away.

“If I had been as lucid that day as I am now,” Carrino said later, “Carmen Ruggiero would already be history.”

Ruggiero declined to be interviewed, saying her work speaks for itself.

___

Sabrina Matrangelo

A daughter of a mafia victim, Matrangelo is now a Libera activist. She was 15 when her mother, Renata Fonte, was assassinated as she came home from a city council meeting in the Puglia town of Nardò.

Fonte, a city councillor for culture, had become a vocal anti-mafia spokeswoman as she tried to protect 1,000 hectares of parkland along the Puglia coastline from illegal development.

Mobsters fired three bullets and killed her, but her legacy lives on: Thanks to her efforts — and the outrage that erupted after her killing — the park remains a protected area and Fonte’s daughter, Matrangelo, has taken up her cause.

“These places will always be in danger,” Matrangelo said from a lookout point above the sea in the Porto Selvaggio Nature Reserve.

“And so the battles of those who shed blood for these civil struggles must walk on our legs, must be perpetuated by our everyday courage,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment