Sonia Sotomayor Points Out How Quickly the Conservative Justices Will Drop Their Stated Principles When It Suits Them

Shirin Ali and Braden Goyette

Fri, June 14, 2024

This is Totally Normal Quote of the Day, a feature highlighting a statement from the news that exemplifies just how extremely normal everything has become.

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.” —Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her dissent from the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Garland v. Cargill

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor is calling bullshit on her conservative colleagues’ rationale for throwing out a 2018 ban on bump stocks, the device used to modify the gun used in the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting—the deadliest in modern U.S. history. The Trump administration reclassified guns with bump stocks as machine guns, thereby banning the device’s use under a 1934 law that heavily restricts access to machine guns.

In Sotomayor’s dissent in Garland v. Cargill, which Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan joined, she called out how her conservative colleagues had basically bent over backwards to redefine the legal definition of a “machine gun.” She noted that these linguistic gymnastics are particularly galling given how much conservative jurists claim to prize textualism—a theory that stresses adhering closely to the plain text of the law and to the ordinary meaning of words.

To drive the point home, Sotomayor came with receipts: She quoted past opinions where each one of the conservative justices in the majority had stressed the importance of textualism—and, specifically, a focus on the ordinary meaning of statutes.

“Every Member of the majority has previously emphasized that the best way to respect congressional intent is to adhere to the ordinary understanding of the terms Congress uses,” wrote Sotomayor, who then cited passages from past opinions where John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett all stressed the importance of textualism. “Today, the majority forgets that principle and substitutes its own view of what constitutes a ‘machine gun’ for Congress’s.”

Congress banned machine guns almost a century ago through the National Firearms Act and, as Sotomayor pointed out, has since updated it to expand the definition of a machine gun to include “any weapon which shoots, or is designed to shoot, automatically … more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.” The federal definition also encompasses “any part designed or intended” to enable automatic fire, which bump stocks plainly are.

Sotomayor cited several dictionary definitions to support her reading of the law and drew attention to the way the majority went out of its way to impose a new, bizarre understanding of the words Congress used. “The majority looks to the internal mechanism that initiates fire, rather than the human act of the shooter’s initial pull, to hold that a ‘single function of the trigger’ means a reset of the trigger mechanism,” Sotomayor wrote. “Its interpretation requires six diagrams and an animation to decipher the meaning of the statutory text.” (Yes, they even included a GIF to back up their argument.)

In this way, the conservative justices’ use of textualism mirrors their use of originalism: Both are supposedly strict philosophies for interpreting law that give them cover to do whatever they want when it suits them. Originalism—the theory that the Constitution must be interpreted through the lens of its original meaning at the time of ratification—has also been misused to put America on a path away from common-sense gun reform, as Jill Filipovic explained in a essay for Slate: “Since 2008, the court has radically departed from centuries of case law on gun regulations and the Second Amendment, making it astoundingly difficult for lawmakers to implement even the most basic and commonsense of gun laws.”

But Sotomayor stressed that the meaning of words does matter. “When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck,” wrote Sotomayor. “A bump-stock-equipped semiautomatic rifle fires ‘automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.’ Because I, like Congress, call that a machinegun, I respectfully dissent.”

Sotomayor Warns Supreme Court's Bump Stock Ruling Will Have 'Deadly Consequences'

Sara Boboltz

Fri, June 14, 2024

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned that the high court’s decision to lift a federal agency’s ban on bump stocks that was put into place after the 2017 Las Vegas massacre would have “deadly consequences.”

The Las Vegas shooter used bump stocks, simple devices that attach to a semiautomatic rifle and create an effect similar to that of a machine gun, to kill 60 people and injure more than 850 others. Then-President Donald Trump instructed the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to implement a ban in response to the tragedy.

But in a 6-3 ruling issued Friday, the Supreme Court said that Congress needed to act to ban bump stocks, and that the ATF had exceeded its authority. The case, Garland v. Cargill, focused on the power of regulatory agencies rather than the Second Amendment.

Congress banned machine guns back in 1934 in response to well-publicized incidents of gang violence that involved weapons like Tommy guns and M16s.

“Congress’s definition of ‘machine gun’ encompasses bump stocks just as naturally as M16s,” Sotomayor wrote in her dissent.

“Today’s decision to reject that ordinary understanding will have deadly consequences,” she said. “The majority’s artificially narrow definition hamstrings the Government’s efforts to keep machine guns from gunmen like the Las Vegas shooter.”

Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson joined in the dissent.

President Joe Biden recalled how the Las Vegas shooter was able to use bump stocks to fire “more than 1000 bullets in just ten minutes, killing 60, wounding hundreds, and traumatizing countless Americans.”

“Americans should not have to live in fear of this mass devastation,” Biden said, urging Congress to act.

The majority, led in their opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, argued that a bump stock does not technically transform a semiautomatic rifle into a machine gun “by a single function of the trigger,” which is the phrasing Congress used in the 1934 National Firearms Act.

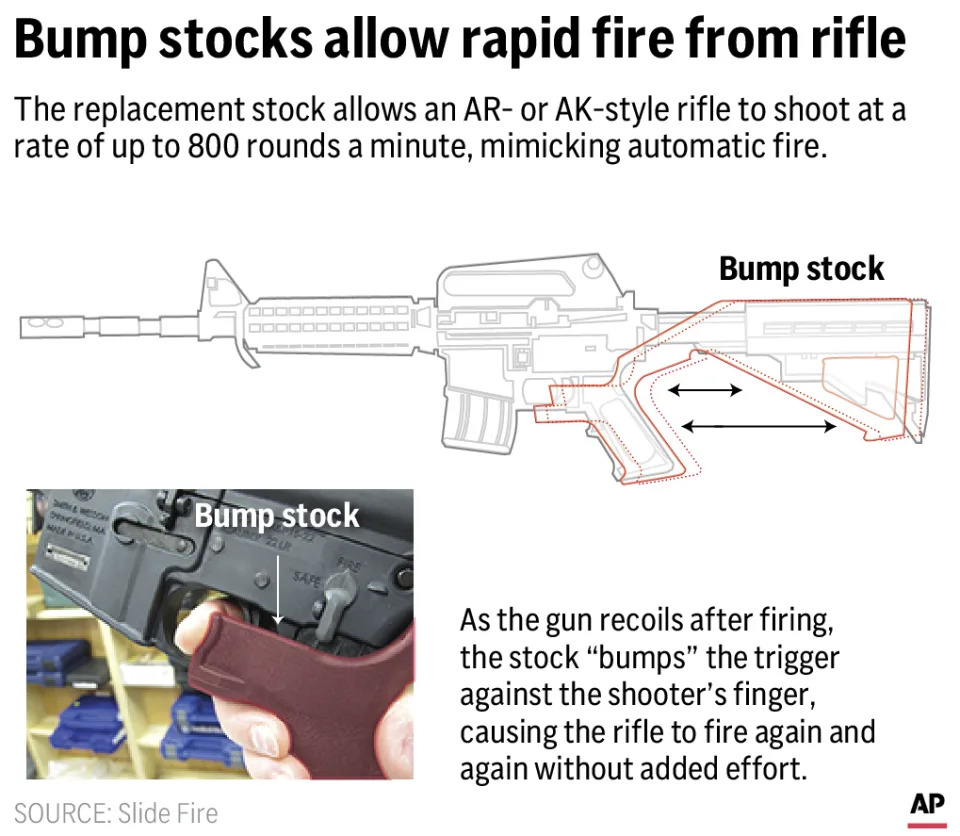

A bump stock allows the shooter to, in one squeezing motion, spray bullets at rates approaching machine gun fire — rates that far exceed what even an experienced shooter can accomplish by pulling the trigger really fast.

“This is not a hard case. All of the textual evidence points to the same interpretation,” Sotomayor wrote.

She compared what happened when a person fired an M16 to what happened when a person fired an AR-15 with a bump stock attached.

“Both shooters pull the trigger only once to fire multiple shots. The only difference is that for an M16, the shooter’s backward pressure makes the rifle fire continuously because of an internal mechanism: The curved lever of the trigger does not move. In a bump-stock-equipped AR–15, the mechanism for continuous fire is external: The shooter’s forward pressure moves the curved lever back and forth against his stationary trigger finger,” she said.

She suggested the majority was actually overcomplicating the issue, writing: “Its interpretation requires six diagrams and an animation to decipher the meaning of the statutory text.”

Sotomayor explained further:

A shooter can fire a bump-stock-equipped semiautomatic rifle in two ways. First, he can choose to fire single shots via distinct pulls of the trigger without exerting any additional pressure. Second, he can fire continuously via maintaining constant forward pressure on the barrel or front grip. The majority holds that the forward pressure cannot constitute a “single function of the trigger” because a shooter can also fire single shots by pulling the trigger. That logic, however, would also exclude a Tommy Gun and an M16, the paradigmatic examples of regulated machine guns in 1934 and today. Both weapons can fire either automatically or semiautomatically.

She put it in even simpler language at another point: “When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.”

What to know about bump stocks and the Supreme Court ruling striking down a ban on the gun accessory

Associated Press

Fri, June 14, 2024

WASHINGTON (AP) — The U.S. Supreme Court has struck down a ban on bump stocks, the gun accessory used in the deadliest shooting in modern American history — a Las Vegas massacre that killed 60 people and injured hundreds more.

The court's conservative majority said Friday that then-President Donald Trump's administration overstepped its authority with the 2019 ban on the firearm attachment, which allows semiautomatic weapons to fire like machine guns.

Here's what to know about the case:

What are bump stocks?

Bump stocks are accessories that replace a rifle's stock, the part that gets pressed against the shooter's shoulder. When a person fires a semiautomatic weapon fitted with a bump stock, it uses the gun's recoil energy to rapidly and repeatedly bump the trigger against the shooter's finger.

That allows the weapon to fire dozens of bullets in a matter of seconds.

Bump stocks were invented in the early 2000s after the expiration of a 1994 ban targeting assault weapons. The federal government approved the sale of bump stocks in 2010 after the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives concluded that guns equipped with the devices should not be considered illegal machine guns under federal law.

According to court documents, more than 520,000 bump stocks were in circulation by the time the government reversed course and imposed a ban that took effect in 2019.

Why were bump stocks banned?

More than 22,000 people were attending a country music festival in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017, when a man opened fire on the crowd from the window of his high-rise hotel room. He fired more than 1,000 rounds in the crowd in 11 minutes, leaving 60 people dead and injuring hundreds more.

Authorities found an arsenal of 23 assault-style rifles in the shooter's hotel room, including 14 weapons fitted with bump stocks.

In the aftermath of the shooting, the ATF reconsidered whether bump stocks could be sold and owned legally. With support from Trump, a Republican, the agency in 2018 ordered a ban on the devices, arguing they turned rifles into illegal machine guns.

Bump stock owners were given until March 2019 to surrender or destroy them.

What did the justices say?

The 6-3 majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas said the ATF did not have the authority to issue the regulation banning bump stocks. The justices said a bump stock is not an illegal machine gun because it doesn’t make the weapon fire more than one shot with a single pull of the trigger.

Justice Samuel Alito, who joined the majority, wrote in a separate opinion that the Las Vegas shooting strengthened the case for changing the law to outlaw bump stocks like machine guns. But that has to happen through action by Congress, not through regulation, he wrote.

The court's three liberal justices opposed the ruling. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent that there's no common sense difference between a machine gun and a semiautomatic firearm with a bump stock.

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck,” she wrote.

Do any states have their own bans?

At least 15 states and the District of Columbia have their own bans on bump stocks, though some could be affected by the high court’s ruling.

Most state laws, however, remain in place because the decision covered the ATF rule, not the constitutionality of state-level bans, according David Pucino, legal director of the gun control think tank Giffords.

Who challenged the ban?

A group called the New Civil Liberties Alliance sued to challenge the bump stock ban on behalf of Michael Cargill, a Texas gun shop owner. Cargill bought two bump stocks in 2018 and then surrendered them once the federal ban took effect, according to court documents.

The case didn't directly address the Second Amendment rights of gun owners. Instead, Cargill's attorneys argued that the ATF overstepped its authority by banning bump stocks. Mark Chenoweth, president of the New Civil Liberties Alliance, said his group wouldn't have sued if Congress had banned them by law.

How did the case end up before the Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court took up the case after lower federal courts delivered conflicting rulings on whether the ATF could ban bump stocks.

The ban survived challenges before the Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the Denver-based 10th Circuit, and the federal circuit court in Washington.

But the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals based in New Orleans struck down the bump stock ban when it ruled in the Texas case last year. The court's majority in the 13-3 decision found that “a plain reading of the statutory language" showed that weapons fitted with bump stocks could not be regulated as machine guns.

Associated Press

Fri, June 14, 2024

WASHINGTON (AP) — The U.S. Supreme Court has struck down a ban on bump stocks, the gun accessory used in the deadliest shooting in modern American history — a Las Vegas massacre that killed 60 people and injured hundreds more.

The court's conservative majority said Friday that then-President Donald Trump's administration overstepped its authority with the 2019 ban on the firearm attachment, which allows semiautomatic weapons to fire like machine guns.

Here's what to know about the case:

What are bump stocks?

Bump stocks are accessories that replace a rifle's stock, the part that gets pressed against the shooter's shoulder. When a person fires a semiautomatic weapon fitted with a bump stock, it uses the gun's recoil energy to rapidly and repeatedly bump the trigger against the shooter's finger.

That allows the weapon to fire dozens of bullets in a matter of seconds.

Bump stocks were invented in the early 2000s after the expiration of a 1994 ban targeting assault weapons. The federal government approved the sale of bump stocks in 2010 after the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives concluded that guns equipped with the devices should not be considered illegal machine guns under federal law.

According to court documents, more than 520,000 bump stocks were in circulation by the time the government reversed course and imposed a ban that took effect in 2019.

Why were bump stocks banned?

More than 22,000 people were attending a country music festival in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017, when a man opened fire on the crowd from the window of his high-rise hotel room. He fired more than 1,000 rounds in the crowd in 11 minutes, leaving 60 people dead and injuring hundreds more.

Authorities found an arsenal of 23 assault-style rifles in the shooter's hotel room, including 14 weapons fitted with bump stocks.

In the aftermath of the shooting, the ATF reconsidered whether bump stocks could be sold and owned legally. With support from Trump, a Republican, the agency in 2018 ordered a ban on the devices, arguing they turned rifles into illegal machine guns.

Bump stock owners were given until March 2019 to surrender or destroy them.

What did the justices say?

The 6-3 majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas said the ATF did not have the authority to issue the regulation banning bump stocks. The justices said a bump stock is not an illegal machine gun because it doesn’t make the weapon fire more than one shot with a single pull of the trigger.

Justice Samuel Alito, who joined the majority, wrote in a separate opinion that the Las Vegas shooting strengthened the case for changing the law to outlaw bump stocks like machine guns. But that has to happen through action by Congress, not through regulation, he wrote.

The court's three liberal justices opposed the ruling. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent that there's no common sense difference between a machine gun and a semiautomatic firearm with a bump stock.

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck,” she wrote.

Do any states have their own bans?

At least 15 states and the District of Columbia have their own bans on bump stocks, though some could be affected by the high court’s ruling.

Most state laws, however, remain in place because the decision covered the ATF rule, not the constitutionality of state-level bans, according David Pucino, legal director of the gun control think tank Giffords.

Who challenged the ban?

A group called the New Civil Liberties Alliance sued to challenge the bump stock ban on behalf of Michael Cargill, a Texas gun shop owner. Cargill bought two bump stocks in 2018 and then surrendered them once the federal ban took effect, according to court documents.

The case didn't directly address the Second Amendment rights of gun owners. Instead, Cargill's attorneys argued that the ATF overstepped its authority by banning bump stocks. Mark Chenoweth, president of the New Civil Liberties Alliance, said his group wouldn't have sued if Congress had banned them by law.

How did the case end up before the Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court took up the case after lower federal courts delivered conflicting rulings on whether the ATF could ban bump stocks.

The ban survived challenges before the Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the Denver-based 10th Circuit, and the federal circuit court in Washington.

But the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals based in New Orleans struck down the bump stock ban when it ruled in the Texas case last year. The court's majority in the 13-3 decision found that “a plain reading of the statutory language" showed that weapons fitted with bump stocks could not be regulated as machine guns.

No comments:

Post a Comment