THE ANTI-FASCIST WAR

Gavin Newsham

Sun, June 2, 2024

June 6 marks 80 years since Allied Forces landed on the beaches of Normandy, France, as part of Operation Overlord, the campaign to defeat the Nazis and liberate Western Europe.

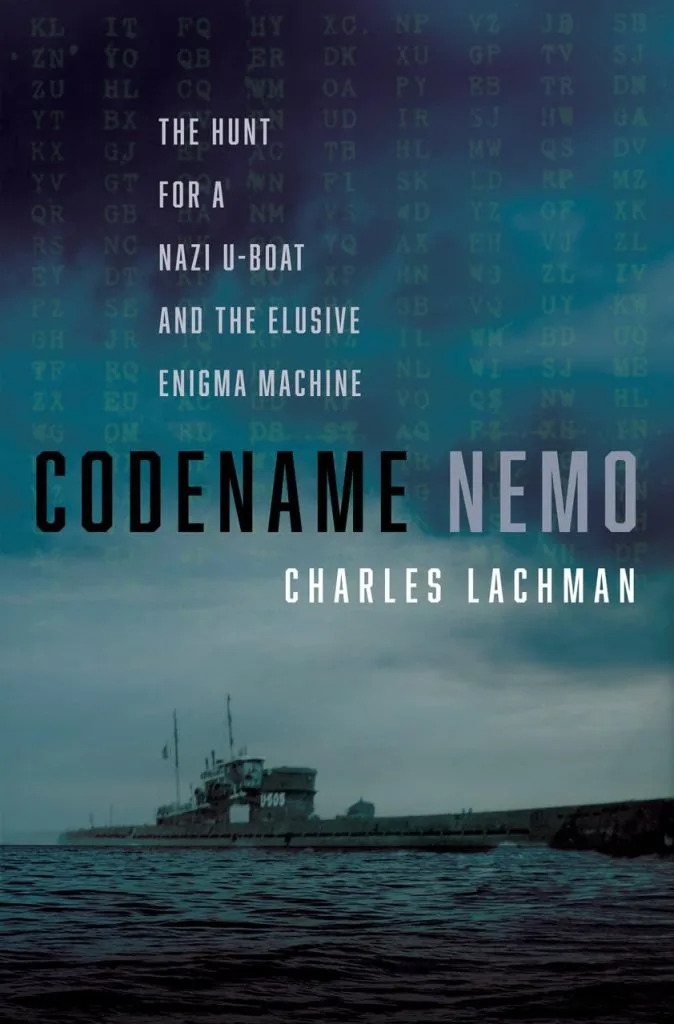

Now, a pair of new books — one charting the story of the Allied invasion, a second examining another key moment in World War II just two days prior to the D-Day landings — reveal the realities, tragedies, challenges and strategic successes of the Allied Forces.

US soldiers stand on the bow of the captured German submarine U-505 in June 1944. Public Domain

On June 4, 1944, the US Navy captured a Nazi U-505 submarine. It was not only the first and only vessel to ever be successfully towed home to America, but also the first time an intact enemy warship had been seized since the War of 1812 with the British.

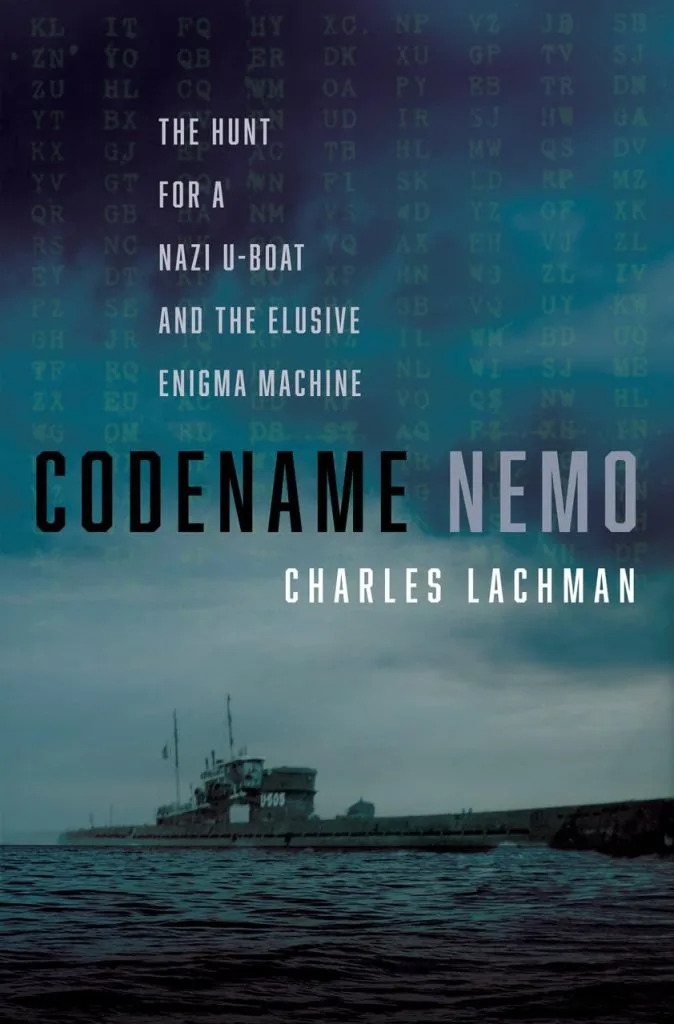

In “Codename Nemo: The Hunt for a Nazi U-Boat and the Elusive Enigma Machine” (Diversion Books), author Charles Lachman recounts the story of how, after months of hunting, a US Navy Task Force, led by Captain Daniel V. Galley on the aircraft carrier USS Guadalcanal tracked down and captured this deadly killing machine.

Captain Daniel V Gallery, Commander of the USS Guadalcanal, which secretly towed the German submarine back to the US. Getty Images

The U-505 had been spotted by two of the Guadalcanal’s fighter planes, running on the surface in the Atlantic Ocean 150 miles off the coast of western Africa, prompting the submarine’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Harald Lange, to dive his vessel deep before Gallery launched depth charges to force it back to the surface.

Fearing his boat was about to break up, Lange ordered his 60-strong crew to abandon ship before readying the 14 detonator charges on board in a bid to destroy it. “Scuttling the submarine is the standard order of business for any well-disciplined U-boat crew. Like the US Navy’s sacred battle cry, “Don’t give up the ship,” the Germans, above all, must keep their vessel from falling into enemy hands,” Lachman wrties.

But with most of the crew now swimming for their lives, there was nobody left to detonate the charges, and when the sub surfaced it was met with a US boarding party, who not only prevented it from sinking but also captured its crew, technology, its encryption codes and an Enigma cipher machine. “It was,” says Lachman, “one of the greatest intelligence windfalls of the war.”

Of the U-505’s crew, just one was killed in the operation. The other 59 became prisoners of war and were taken across the Atlantic to a POW camp in Ruston, Louisiana. “Every now and then, the Guadalcanalrises on an ocean swell, and that’s when the POWs catch sight of their beloved U-505and realize she’s being towed by the carrier.

“Most distressing of all, she’s flying an American flag.”

Author Charles Lachman Courtesy of Charles Lachman

But as Lachman explains, it wasn’t just the Stars and Stripes flying strong. “Below Old Glory is a smaller flag – the Nazi flag – with swastika. In Navy tradition, it is a symbol of victor over vanquished.”

It wasn’t until eight days after Germany’s unconditional surrender in May 1945 that the Navy Office of Public Relations finally revealed that the U-505 had been captured.

None of the 3,000 sailors involved in the Task Force ever uttered a word about the capture in the 11 months that had passed.

Master-at-Arms Leon S. Bednarczyk with his crew during the journey to bring the U-sub back to the USA. Courtesy of the US Navy

Indeed, the cover-up was so successful that German high command believed their U-505 was on the ocean floor somewhere off of Africa, along with its crew and intelligence secrets. “For Captain Dan Gallery, this is perhaps Codename Nemo’s most impressive achievement,” writes Lachman. “The boys did keep their mouths shut,” says Gallery. “I think this speaks very highly indeed for the devotion to duty and sense of responsibility.” Today, the U-505 is on display in Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry.

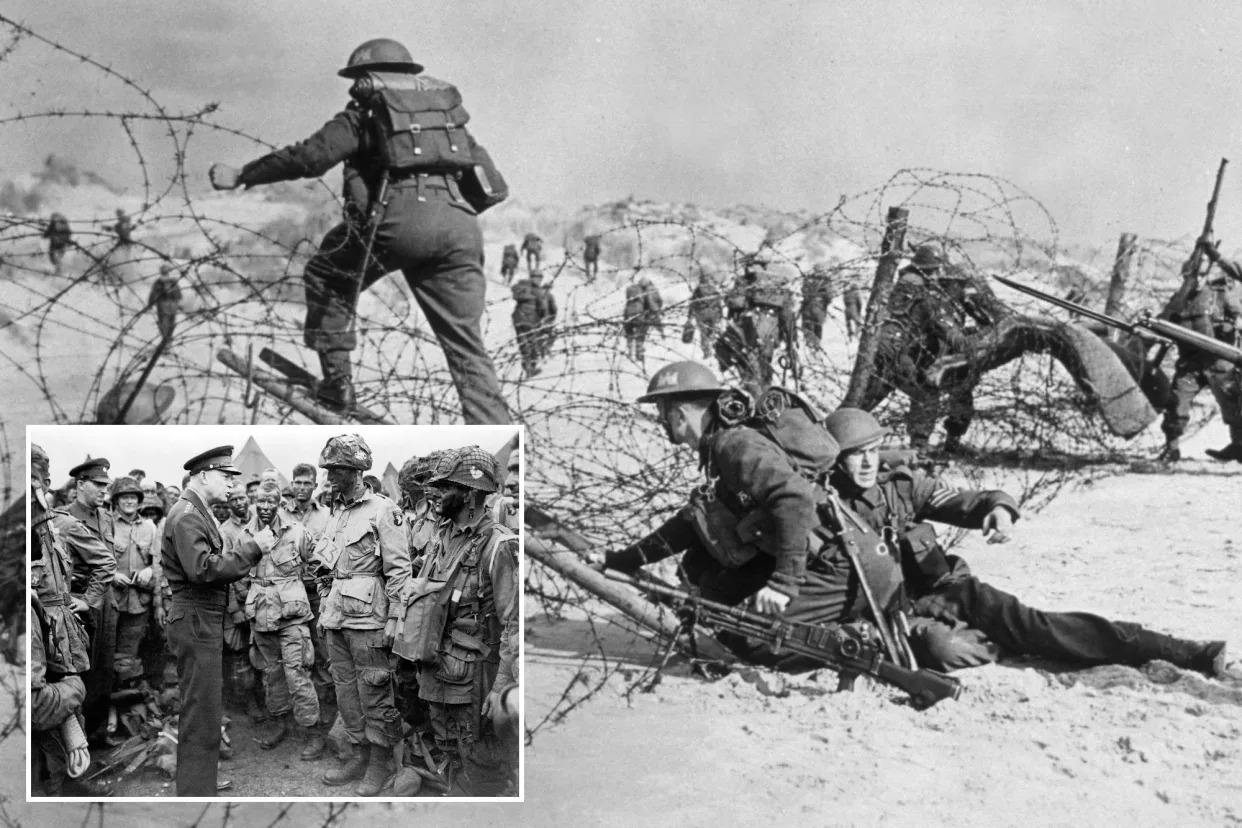

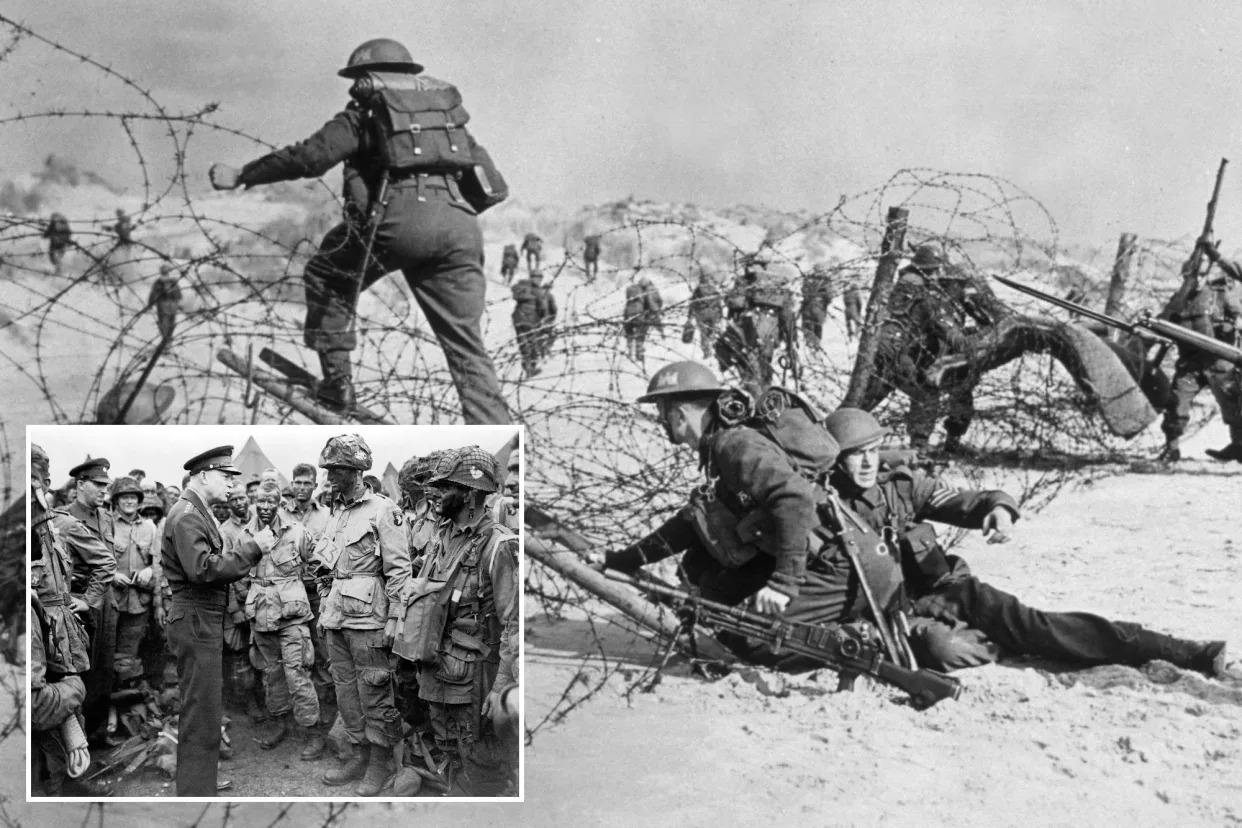

Two days after the U-505’s capture, more than 156,000 Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy, as Operation Overlord, the campaign to wrest control back from the Nazis in Europe, entered a decisive phase.

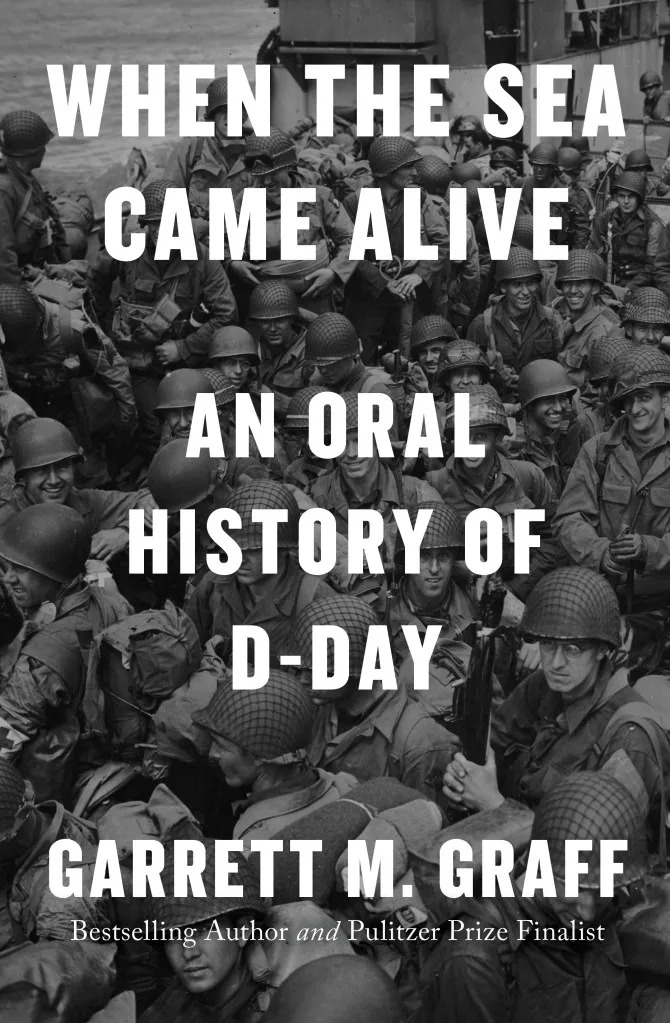

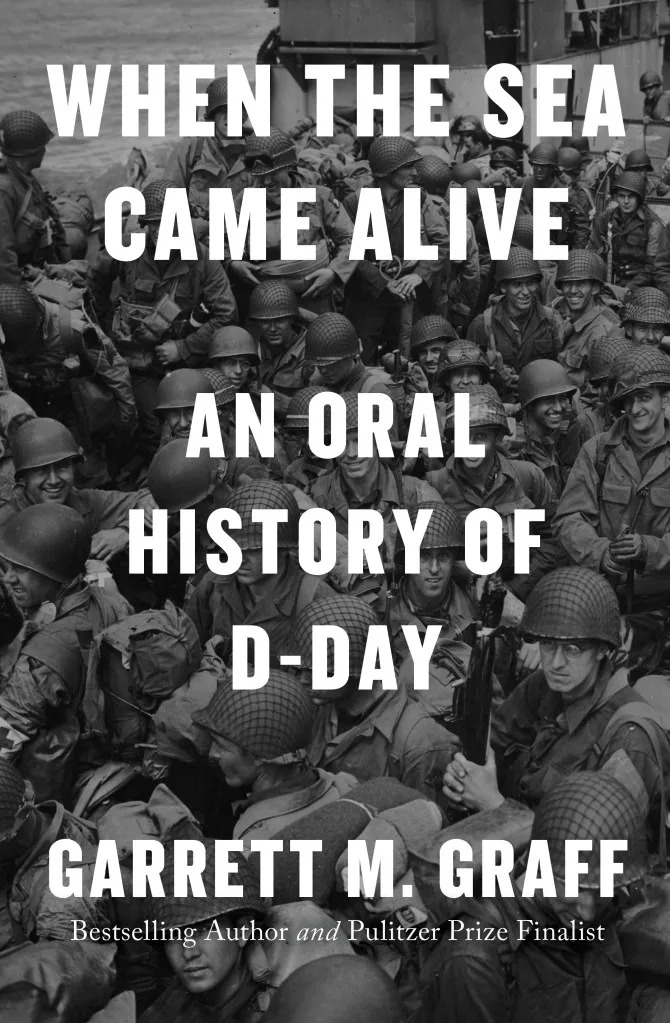

In “When The Sea Came Alive: An Oral History of D-Day” (Avid Reader Press) historian Garrett Graff has gathered recollections of more than 700 people involved in this pivotal moment of World War II. “June 6, 1944, is one of the most famous single days in all of human history,” he writes.

“The official launch of Operation Overlord marks a feat of unprecedented human audacity, a mission more complex than anything ever seen and a key turning point in the fight for a cause among the most noble humans have ever fought.”

Author Garrett M. Graff yassine el mansouri

While some names are familiar, the majority will feel new. They are soldiers and French villagers, German troops and the housewives left behind, who tell their stories, creating an intimate report of D-Day in often visceral detail.

“Operation Overlord is a story dominated by historic figures — Winston Churchill, Dwight Eisenhower, George Marshall, Omar Bradley — and the big, world-shaping decisions they make,” writes Graff. Still, he adds, “the greatest names, as it turns out, are the ones you don’t know.” The oral history covers everything from preparations for the invasion to US troops arriving in Britain at the rate of 5,000 each day between 1943 and 1944.

One of the tens of thousands of aircraft that flew over Europe during D-Day. Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Operation Overlord was the largest seaborne invasion in history. During the 24 hours of June 6, the Strategic Air Forces — with over 11,500 aircraft — flew 5,309 sorties to drop 10,395 tons of bombs, while aircraft of the tactical forces flew a further 5,276 sorties.

When the invasion launched, over 73,000 US troops landed on Omaha and Utah beaches, supported by nearly 7,000 naval vessels. They were joined by over 61,000 British soldiers who landed at Gold and Sword Beaches and another 21,000 Canadians attacking at Juno Beach.

“The battle scene was the most awesome terrible thing a human being could ever witness,” recalls Seaman Exum Pike, on the submarine chaser USS PC-565. “Looking back on that day, after these many years, I have two grown sons and as I have often told them boys I have no fear of hell because I have already been there.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Montgomery, and Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey, and G.G. Simonds examine a map in France after the allied invasion of Normandy. Bettmann Archive

Like countless others, Capt. George Mabry, an operations officer with 8th Infantry Regiment, witnessed that hell. “We’d been trained that once you hit the beach, you run. Ahead of me was a man carrying ammunition. A round hit the top of his head . . . and this man’s body completely disappeared,” he says. “I felt something hit my thigh; it was his thumb.”

Sgt. Jerry Salinger, Counter Intelligence Corps, puts it more graphically. “You never really get the smell of burned flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live.”

General Dwight D Eisenhower talking with American paratroopers in Britain on the evening of June 5, 1944, as they prepared for the Invasion of Normandy. Getty Images

Some 4,414 Allied soldiers died on Normandy’s beaches. “When I landed D-Day morning, I had 35 men in my platoon and in my boat,” says Lt. John J. Reville, 5th Ranger Battalion. “At the end of seven days, there was myself and four men left.”

By June 30, the Allied forces had more than 850,000 troops, nearly 150,000 vehicles and 57,000 tons of supplies in Normandy, paving the way for victory.

It’s best summed up by Charles R. Sullivan of the 111th Naval Construction Battalion. “Normandy and D-Day remain vivid, as if it only happened yesterday. What we did was important and worthwhile,” he says. “How many ever get to say that about a day in their lives?”

CANADIAN ARMY, EH

‘Sorry for throwing grenades in your cellar.’ The unusual fate of the first house liberated in D-Day beach landings

Joshua Berlinger, CNN

Mon, June 3, 2024

Their target was an elegant, two-story villa sitting solitary on a misty beach. No houses stood nearby, just minefields, military pillboxes and enemy machine gun posts.

It was D-Day, and on that overcast morning on June 6, 1944, 10 boats filled with Canadian troops crossed the English Channel’s choppy waters to head for the 1,500 yard stretch of Normandy coastline where the house was located.

These soldiers’ small part in the world’s largest seaborne invasion was to capture the coastal town of Bernieres-sur-Mer. Seizing the villa would be a key objective. Aerial photographs had led them to falsely believe that it was a railway station. Regardless of what it was, allied war planners wanted to use it as a lookout toward the sea once the beach was captured.

Canadian soldiers from 9th Brigade are seen landing at Juno Beach on D-Day. The house in the center managed to survive the battle. - Imperial War Museum/AFP/Getty Images

To get there, the troops would have to cross the open beach. It would be an assault landing, with almost nowhere to hide.

The troops hit the shore at 7:15 a.m. and were met by unrelenting machine gun and mortar fire. Within 20 minutes, the soldiers that had managed to survive the initial onslaught reached the villa and expelled the German troops inside. It was, in all likelihood, the first house to be liberated after the beach landings during Operation Overlord.

The cost was extreme. About 100 Canadians died on that beach in the first few minutes of the battle.

The villa, though riddled with bullet holes and other battle scars, was intact.

Eighty years later, the half-timbered home remains. It is called “La Maison de Canadiens” in French, or Canada House in English, and it is now a memorial dedicated to the Canadians who gave their lives to liberate France thanks to the work of one French couple.

Opening the door to strangers

The half-timbered home that many Canadian soldiers saw has been refurbished, but still looks much like it did on D-Day. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

After Nicole and Herve Hoffer married in 1975 and then had children, they began spending more time at the family’s vacation home Bernieres-sur-Mer. Nicole noticed that people walking by on the boardwalk between the house and the beach often stopped to take photographs of the building. She asked her husband why, but he didn’t know.

The villa was constructed in 1928 by a Parisian man who wanted his two children to have vacation homes of their own. So he built two adjoining houses, with one side for his daughter and another for his son. Herve Hoffer’s grandparents purchased the daughter’s side in 1936.

The Hoffers knew that the house had been occupied by the Germans in 1942 and then returned to their family five years later, luckily relatively intact. Countless other homes had been destroyed by the allied bombardment during the Battle of Normandy.

But why people kept photographing their house was a mystery. So the Hoffers began inquiring, and many of the people taking pictures turned out to be Canadian veterans on a pilgrimage back to where they landed on D-Day. The couple would invite them inside for a beer, a glass of Calvados – an apple brandy native to Normandy – or a meal, over which former soldiers shared their stories.

Nicole Hoffer has for decades opened the doors to her summer home to Canadian veterans returning to Juno Beach. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

“Even in my own family, I’ve been criticized … how could I open the door to strangers?” Nicole Hoffer said. “I’d say, well, if the foreigners hadn’t come, you might not be here today. They brought us freedom, many at the risk of their lives.”

The Hoffers typically found the first moments of an encounter particularly moving. As veterans sat down for the first time, they’d look out the window as if they were in a film that had taken a decades-long pause, Nicole Hoffer said. Then they would share stories that even their families and friends had never heard.

With each meeting, the story of the Hoffer family vacation home emerged, piece by piece.

The family learned that when Canadian troops landed at H-Hour, the beginning of the amphibious assault, the Germans that were inside the home fired at them from a machine gun mounted on a bench and aimed outside the front window. Many of the soldiers who were not gunned down hid behind a beach wall near the home, from which they were able to regroup and expel the German troops from the house.

Many soldiers who return, Nicole Hoffer said, are surprised to find the wall gone, buried by sand over the years. The house, however, still looks mostly the same.

A summer home filled with war memories

The Hoffers have collected countless souvenirs over the years, including a cross (center) that one veteran discovered during the war. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

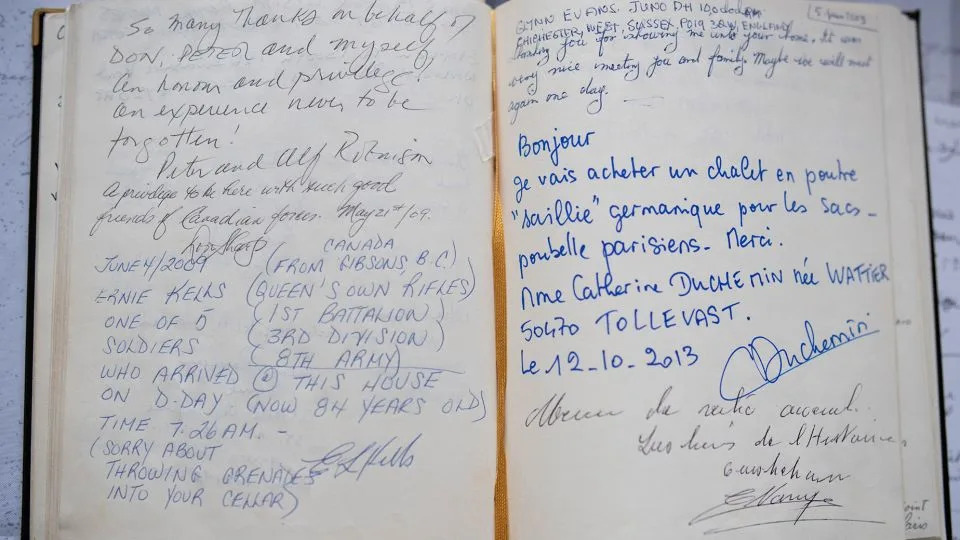

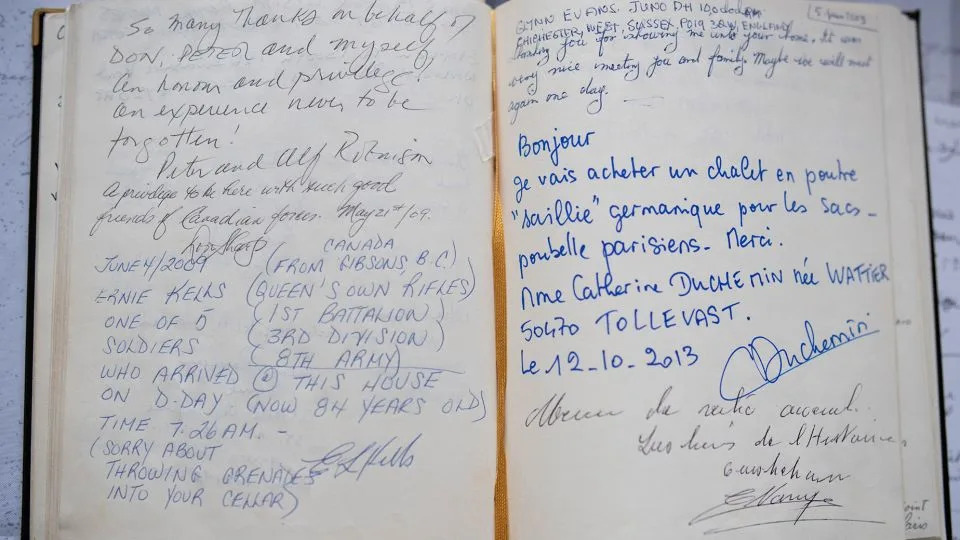

The Hoffers found that as veterans kept coming back over the years, more and more began to bring souvenirs for them, so many that their summer home is now effectively doubles as a museum. Their guestbook has collected hundreds – if not thousands – of signatures from veterans and their families returning to Juno Beach. One signer, Ernie Kells, even apologized for tossing grenades into their basement to flush out German troops.

Donated medals, flags, paintings and other keepsakes adorn the walls, including a cross featuring a Jesus icon whose arm had apparently been blown off while in a soldier’s pocket. The man had found the cross intact in a nearby house, and shrapnel that hit it may have saved his life. Years later, on his death bed, the man had asked his family to return the cross to the Hoffer’s home.

“In the house, you find a lot of memories,” she said.

Their guestbook is filled with hundreds of entries, including that of one soldier who tossed grenades into their cellar. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

The Hoffers eventually began hosting their own ceremony to honor Canada’s fallen soldiers. About a week before June 6, they light a paraffin lantern and leave it burning on the balcony. Then on the evening of the anniversary, bagpipers play as the lamp is tossed into the sea, while guests place flowers and crosses where the water meets the sand.

Herve Hoffer was responsible for throwing the lamp himself until his sudden death in 2017, To honor his memory, Nicole Hoffer has opened the house to even more veterans than when he was alive.

“Now there’s trips, entire buses who come and ask if we can open the house,” she said.

For the 80th anniversary of D-Day this year, Hoffer is expecting a larger crowd. Not only will there be the usual contingent of visitors to her home, but the west side of the house will open to the public for the first time since being purchased by the local government. It is hosting an exhibit featuring the testimony of French men and women who lived through D-Day as children.

Photographs of the landing at Juno Beach are displayed on the wall next to Canada House. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

VALERIE KOMOR

Updated Mon, June 3, 2024

NEW YORK (AP) — When Associated Press correspondent Don Whitehead arrived with other journalists in southern England to cover the Allies' imminent D-Day invasion of Normandy, a U.S. commander offered them a no-nonsense welcome.

“We’ll do everything we can to help you get your stories and to take care of you. If you’re wounded, we’ll put you in a hospital. If you’re killed, we’ll bury you. So don’t worry about anything," said Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Heubner of the U.S. Army 1st Infantry Division.

It was early June 1944 — just before the long-anticipated Normandy landings that ultimately liberated France from Nazi occupation and helped precipitate Nazi Germany's surrender 11 months later.

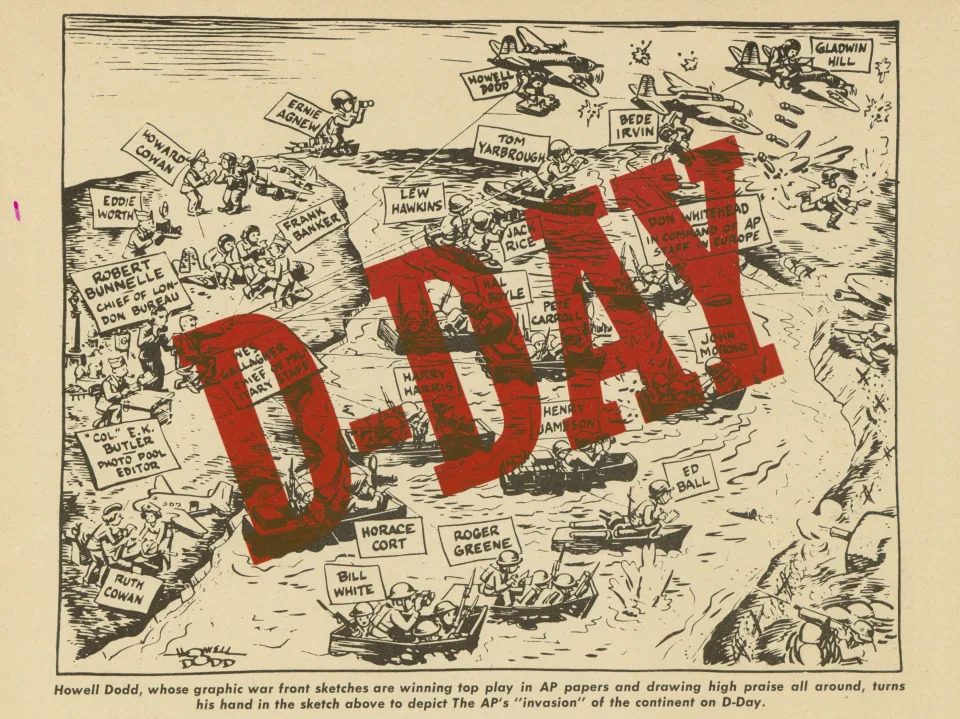

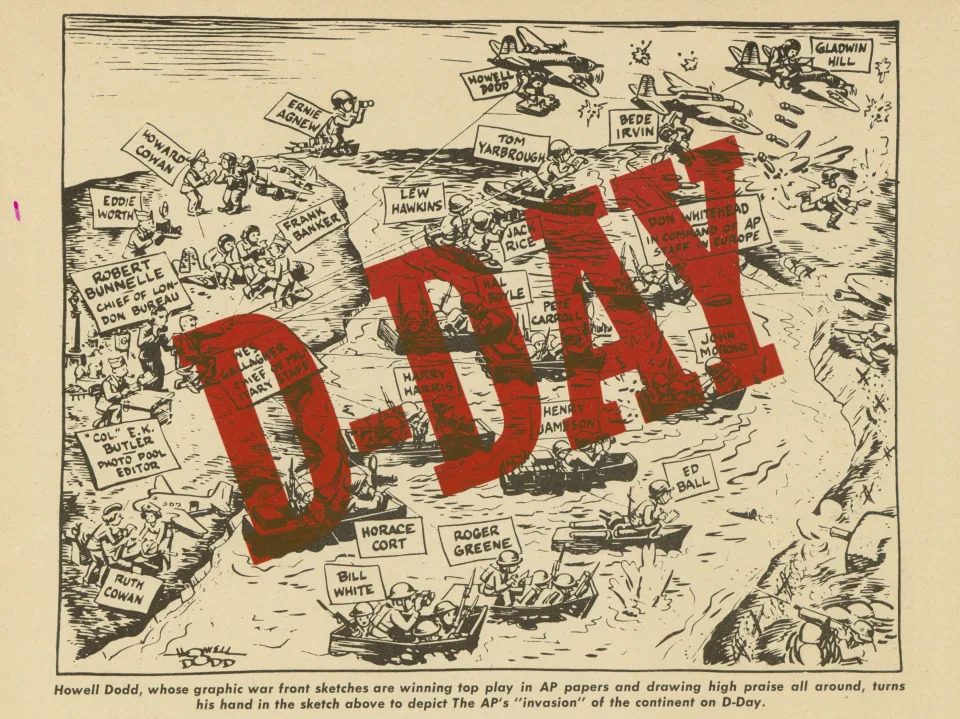

On D-Day morning, June 6, 1944, AP had reporters, artists and photographers in the air, on the choppy waters of the English Channel, in London, and at English departure ports and airfields. Veteran war correspondent Wes Gallagher — who would later run the entire Associated Press — directed AP's team from the headquarters in Portsmouth, England, of Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The greatest armada ever assembled — nearly 7,000 ships and boats, supported by more than 11,000 planes — carried almost 133,000 troops across the Channel to establish toeholds on five heavily defended beaches; they were code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword and stretched across 80 kilometers (50 miles) of Normandy coast. More than 9,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded in the first 24 hours.

Having heard on German radio that the landings had begun, Gallagher hurried to the British Ministry of Information to await the official communique. It came just before 9 a.m. with this brief instruction: “Gentlemen, you have exactly 33 minutes to prepare your dispatches.”

At precisely 9:32 a.m., the doors opened and the journalists poured out to release their reports. Gallagher’s FLASH appeared via teletype in the New York headquarters of AP just one minute later.

LONDON—EISENHOWERS HEADQUARTERS ANNOUNCES ALLIES LAND IN FRANCE.

The 1,300-word story that followed began: “Allied troops landed on the Normandy coast of France in tremendous strength by cloudy daylight today and stormed several miles inland with tanks and infantry in the grand assault which Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower called a crusade in which ‘we will accept nothing less than full victory.’”

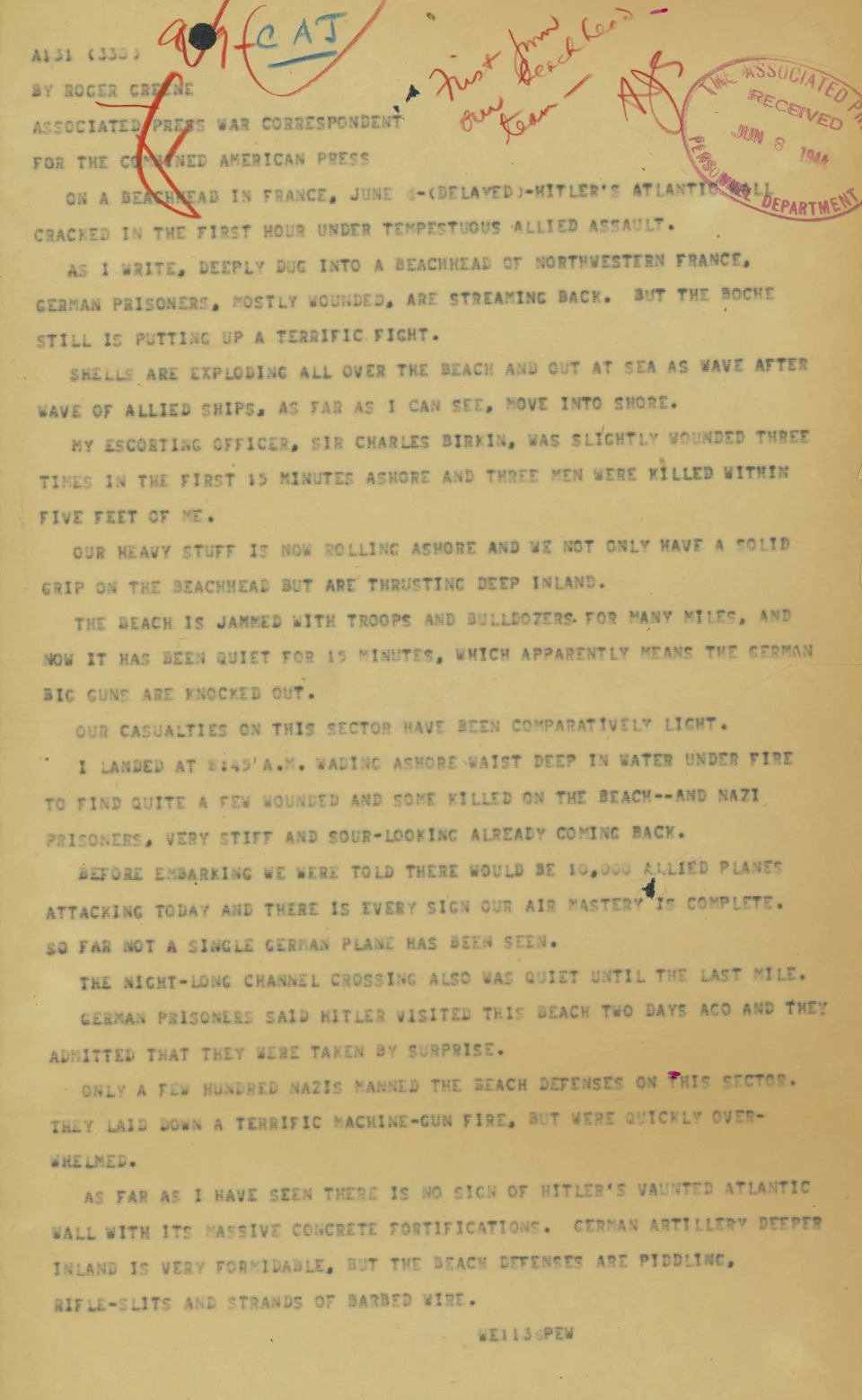

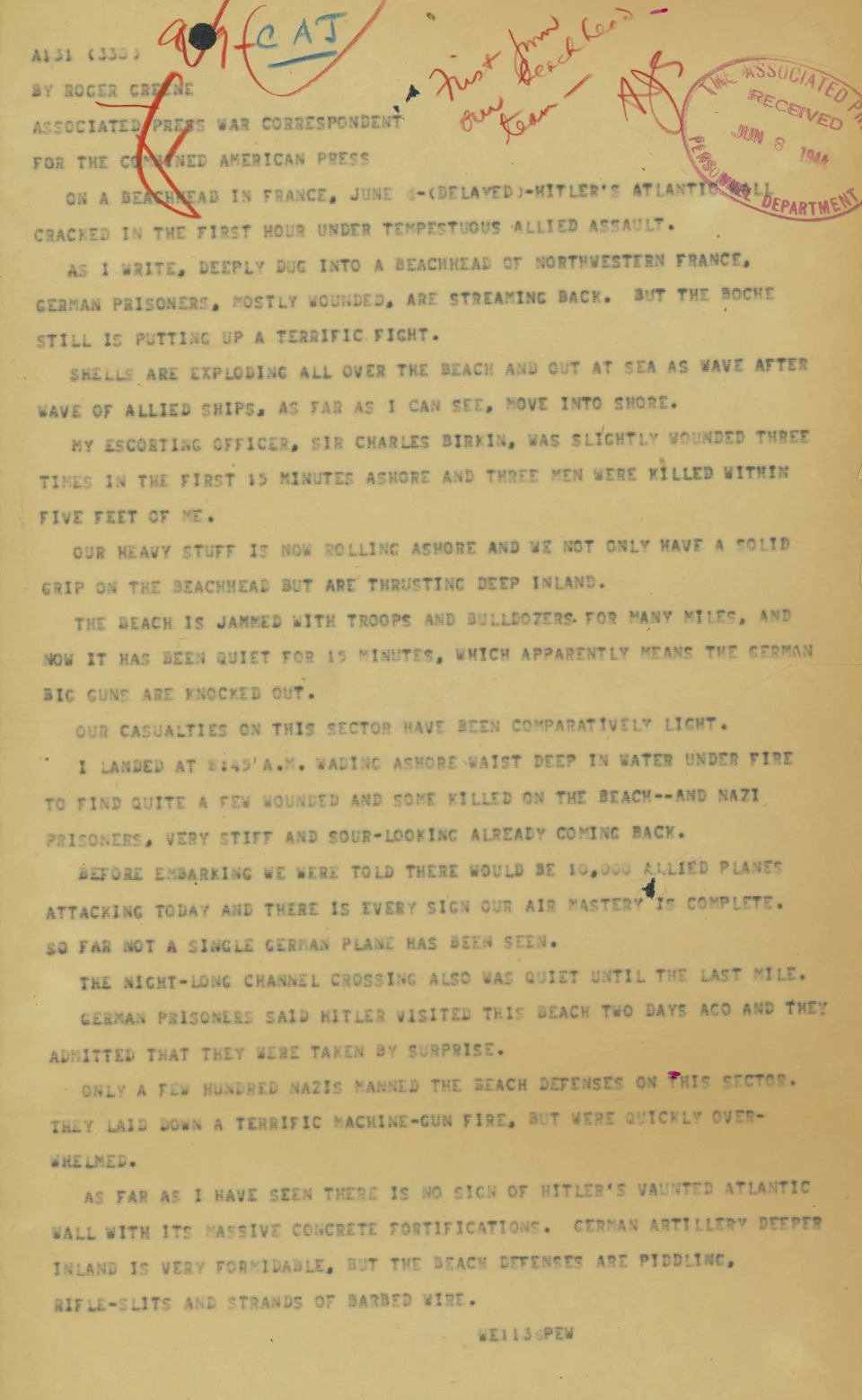

As men on either side of him were killed, AP correspondent Roger Greene waded ashore on the eastern end of the landing front. Sheltering in a bomb crater, Greene pounded out the first AP report from the beachhead, with wind flicking sand into his typewriter keys and rattling the paper.

“Hitler’s Atlantic Wall cracked in the first hour under tempestuous Allied assault," he wrote.

On Omaha, the deadliest invasion beach, AP's Whitehead lost his bedroll and equipment and nearly his life as he landed with the 16th Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division.

“So many guys were getting killed that I stopped being afraid. I was resigned to being killed, too," he later recalled.

He witnessed German heavy machine-gun fire, mortar and artillery rounds raking landing craft and pinning down U.S. soldiers, vehicles and supplies that “began to pile up on the beach at an alarming rate.”

Whitehead never forgot the calmness of Col. George A. Taylor urging troops onward by yelling: “Gentleman, we’re being killed on the beach. Let’s go inland and be killed.”

The Battle of Normandy was underway, with Allied forces pushing off the beaches and fighting their way inland in the following days and weeks. By June 30, the Allies had landed 850,000 soldiers, nearly 150,000 vehicles and more than half a million tons of supplies.

Casualties mounted on all sides and among French civilians. By the second half of August, with Paris being liberated, more than 225,000 Allied troops had been killed, wounded or were missing. On the German side, more than 240,000 had been killed or wounded and 200,000 captured.

The dead included 33-year-old AP photographer Bede Irvin, killed July 25 near the Normandy town of Saint Lo as he was photographing an Allied bombardment that went horribly wrong, with some of the bombers mistakenly dropping their payloads on their own forces.

As well as Irvin — hit by shrapnel as he was diving for the shelter of a roadside ditch — more than 100 American soldiers were killed and almost 500 others wounded, said Ben Brands, a historian with the American Battle Monuments Commission. It manages the the Normandy American Cemetery where Irvin is buried, overlooking Omaha Beach.

On Monday, colleagues from AP’s Paris bureau, covering the 80th anniversary of the landings, laid flowers at the foot of the white stone cross on his grave. Irvin's is one of 9,387 graves in what was the first American cemetery in Europe of World War II, set up two days after D-Day.

In its September 1944 edition, AP's in-house magazine said the native of Des Moines, Iowa, had until then survived some of the worst fighting in Normandy and “had only one complaint — that he was not seeing enough action.”

In a letter after his death to one of Irvin's AP colleagues, his widow, Kathryne, poured out her sorrow. Muriel Rambert, an ABMC guide at the cemetery, read out an extract Monday at his grave, after she'd used sand from Omaha Beach to highlight Irvin's name on his headstone and planted American and French flags in front of it.

“There are so many hopes and plans between a husband and wife,” she said, reading from the letter. “Plans that won't for Bede and me ever come true.”

___

Valerie Komor is AP's director of corporate archives. Associated Press writer John Leicester in Colleville-sur-Mer, France, contributed to this report.

Muriel Rambert, interpretive guide at American Battle Monuments Commission, shows a portrait of Associated Press photographer Bede Irvin, at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France on Monday, June 3, 2024

Why D-Day was even more spectacular than remembered

Gavin Newsham

Sun, June 2, 2024

June 6 marks 80 years since Allied Forces landed on the beaches of Normandy, France, as part of Operation Overlord, the campaign to defeat the Nazis and liberate Western Europe.

Now, a pair of new books — one charting the story of the Allied invasion, a second examining another key moment in World War II just two days prior to the D-Day landings — reveal the realities, tragedies, challenges and strategic successes of the Allied Forces.

US soldiers stand on the bow of the captured German submarine U-505 in June 1944. Public Domain

On June 4, 1944, the US Navy captured a Nazi U-505 submarine. It was not only the first and only vessel to ever be successfully towed home to America, but also the first time an intact enemy warship had been seized since the War of 1812 with the British.

In “Codename Nemo: The Hunt for a Nazi U-Boat and the Elusive Enigma Machine” (Diversion Books), author Charles Lachman recounts the story of how, after months of hunting, a US Navy Task Force, led by Captain Daniel V. Galley on the aircraft carrier USS Guadalcanal tracked down and captured this deadly killing machine.

Captain Daniel V Gallery, Commander of the USS Guadalcanal, which secretly towed the German submarine back to the US. Getty Images

The U-505 had been spotted by two of the Guadalcanal’s fighter planes, running on the surface in the Atlantic Ocean 150 miles off the coast of western Africa, prompting the submarine’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Harald Lange, to dive his vessel deep before Gallery launched depth charges to force it back to the surface.

Fearing his boat was about to break up, Lange ordered his 60-strong crew to abandon ship before readying the 14 detonator charges on board in a bid to destroy it. “Scuttling the submarine is the standard order of business for any well-disciplined U-boat crew. Like the US Navy’s sacred battle cry, “Don’t give up the ship,” the Germans, above all, must keep their vessel from falling into enemy hands,” Lachman wrties.

But with most of the crew now swimming for their lives, there was nobody left to detonate the charges, and when the sub surfaced it was met with a US boarding party, who not only prevented it from sinking but also captured its crew, technology, its encryption codes and an Enigma cipher machine. “It was,” says Lachman, “one of the greatest intelligence windfalls of the war.”

Of the U-505’s crew, just one was killed in the operation. The other 59 became prisoners of war and were taken across the Atlantic to a POW camp in Ruston, Louisiana. “Every now and then, the Guadalcanalrises on an ocean swell, and that’s when the POWs catch sight of their beloved U-505and realize she’s being towed by the carrier.

“Most distressing of all, she’s flying an American flag.”

Author Charles Lachman Courtesy of Charles Lachman

But as Lachman explains, it wasn’t just the Stars and Stripes flying strong. “Below Old Glory is a smaller flag – the Nazi flag – with swastika. In Navy tradition, it is a symbol of victor over vanquished.”

It wasn’t until eight days after Germany’s unconditional surrender in May 1945 that the Navy Office of Public Relations finally revealed that the U-505 had been captured.

None of the 3,000 sailors involved in the Task Force ever uttered a word about the capture in the 11 months that had passed.

Master-at-Arms Leon S. Bednarczyk with his crew during the journey to bring the U-sub back to the USA. Courtesy of the US Navy

Indeed, the cover-up was so successful that German high command believed their U-505 was on the ocean floor somewhere off of Africa, along with its crew and intelligence secrets. “For Captain Dan Gallery, this is perhaps Codename Nemo’s most impressive achievement,” writes Lachman. “The boys did keep their mouths shut,” says Gallery. “I think this speaks very highly indeed for the devotion to duty and sense of responsibility.” Today, the U-505 is on display in Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry.

Two days after the U-505’s capture, more than 156,000 Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy, as Operation Overlord, the campaign to wrest control back from the Nazis in Europe, entered a decisive phase.

In “When The Sea Came Alive: An Oral History of D-Day” (Avid Reader Press) historian Garrett Graff has gathered recollections of more than 700 people involved in this pivotal moment of World War II. “June 6, 1944, is one of the most famous single days in all of human history,” he writes.

“The official launch of Operation Overlord marks a feat of unprecedented human audacity, a mission more complex than anything ever seen and a key turning point in the fight for a cause among the most noble humans have ever fought.”

Author Garrett M. Graff yassine el mansouri

While some names are familiar, the majority will feel new. They are soldiers and French villagers, German troops and the housewives left behind, who tell their stories, creating an intimate report of D-Day in often visceral detail.

“Operation Overlord is a story dominated by historic figures — Winston Churchill, Dwight Eisenhower, George Marshall, Omar Bradley — and the big, world-shaping decisions they make,” writes Graff. Still, he adds, “the greatest names, as it turns out, are the ones you don’t know.” The oral history covers everything from preparations for the invasion to US troops arriving in Britain at the rate of 5,000 each day between 1943 and 1944.

One of the tens of thousands of aircraft that flew over Europe during D-Day. Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Operation Overlord was the largest seaborne invasion in history. During the 24 hours of June 6, the Strategic Air Forces — with over 11,500 aircraft — flew 5,309 sorties to drop 10,395 tons of bombs, while aircraft of the tactical forces flew a further 5,276 sorties.

When the invasion launched, over 73,000 US troops landed on Omaha and Utah beaches, supported by nearly 7,000 naval vessels. They were joined by over 61,000 British soldiers who landed at Gold and Sword Beaches and another 21,000 Canadians attacking at Juno Beach.

“The battle scene was the most awesome terrible thing a human being could ever witness,” recalls Seaman Exum Pike, on the submarine chaser USS PC-565. “Looking back on that day, after these many years, I have two grown sons and as I have often told them boys I have no fear of hell because I have already been there.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Montgomery, and Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey, and G.G. Simonds examine a map in France after the allied invasion of Normandy. Bettmann Archive

Like countless others, Capt. George Mabry, an operations officer with 8th Infantry Regiment, witnessed that hell. “We’d been trained that once you hit the beach, you run. Ahead of me was a man carrying ammunition. A round hit the top of his head . . . and this man’s body completely disappeared,” he says. “I felt something hit my thigh; it was his thumb.”

Sgt. Jerry Salinger, Counter Intelligence Corps, puts it more graphically. “You never really get the smell of burned flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live.”

General Dwight D Eisenhower talking with American paratroopers in Britain on the evening of June 5, 1944, as they prepared for the Invasion of Normandy. Getty Images

Some 4,414 Allied soldiers died on Normandy’s beaches. “When I landed D-Day morning, I had 35 men in my platoon and in my boat,” says Lt. John J. Reville, 5th Ranger Battalion. “At the end of seven days, there was myself and four men left.”

By June 30, the Allied forces had more than 850,000 troops, nearly 150,000 vehicles and 57,000 tons of supplies in Normandy, paving the way for victory.

It’s best summed up by Charles R. Sullivan of the 111th Naval Construction Battalion. “Normandy and D-Day remain vivid, as if it only happened yesterday. What we did was important and worthwhile,” he says. “How many ever get to say that about a day in their lives?”

CANADIAN ARMY, EH

‘Sorry for throwing grenades in your cellar.’ The unusual fate of the first house liberated in D-Day beach landings

Joshua Berlinger, CNN

Mon, June 3, 2024

Their target was an elegant, two-story villa sitting solitary on a misty beach. No houses stood nearby, just minefields, military pillboxes and enemy machine gun posts.

It was D-Day, and on that overcast morning on June 6, 1944, 10 boats filled with Canadian troops crossed the English Channel’s choppy waters to head for the 1,500 yard stretch of Normandy coastline where the house was located.

These soldiers’ small part in the world’s largest seaborne invasion was to capture the coastal town of Bernieres-sur-Mer. Seizing the villa would be a key objective. Aerial photographs had led them to falsely believe that it was a railway station. Regardless of what it was, allied war planners wanted to use it as a lookout toward the sea once the beach was captured.

Canadian soldiers from 9th Brigade are seen landing at Juno Beach on D-Day. The house in the center managed to survive the battle. - Imperial War Museum/AFP/Getty Images

To get there, the troops would have to cross the open beach. It would be an assault landing, with almost nowhere to hide.

The troops hit the shore at 7:15 a.m. and were met by unrelenting machine gun and mortar fire. Within 20 minutes, the soldiers that had managed to survive the initial onslaught reached the villa and expelled the German troops inside. It was, in all likelihood, the first house to be liberated after the beach landings during Operation Overlord.

The cost was extreme. About 100 Canadians died on that beach in the first few minutes of the battle.

The villa, though riddled with bullet holes and other battle scars, was intact.

Eighty years later, the half-timbered home remains. It is called “La Maison de Canadiens” in French, or Canada House in English, and it is now a memorial dedicated to the Canadians who gave their lives to liberate France thanks to the work of one French couple.

Opening the door to strangers

The half-timbered home that many Canadian soldiers saw has been refurbished, but still looks much like it did on D-Day. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

After Nicole and Herve Hoffer married in 1975 and then had children, they began spending more time at the family’s vacation home Bernieres-sur-Mer. Nicole noticed that people walking by on the boardwalk between the house and the beach often stopped to take photographs of the building. She asked her husband why, but he didn’t know.

The villa was constructed in 1928 by a Parisian man who wanted his two children to have vacation homes of their own. So he built two adjoining houses, with one side for his daughter and another for his son. Herve Hoffer’s grandparents purchased the daughter’s side in 1936.

The Hoffers knew that the house had been occupied by the Germans in 1942 and then returned to their family five years later, luckily relatively intact. Countless other homes had been destroyed by the allied bombardment during the Battle of Normandy.

But why people kept photographing their house was a mystery. So the Hoffers began inquiring, and many of the people taking pictures turned out to be Canadian veterans on a pilgrimage back to where they landed on D-Day. The couple would invite them inside for a beer, a glass of Calvados – an apple brandy native to Normandy – or a meal, over which former soldiers shared their stories.

Nicole Hoffer has for decades opened the doors to her summer home to Canadian veterans returning to Juno Beach. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

“Even in my own family, I’ve been criticized … how could I open the door to strangers?” Nicole Hoffer said. “I’d say, well, if the foreigners hadn’t come, you might not be here today. They brought us freedom, many at the risk of their lives.”

The Hoffers typically found the first moments of an encounter particularly moving. As veterans sat down for the first time, they’d look out the window as if they were in a film that had taken a decades-long pause, Nicole Hoffer said. Then they would share stories that even their families and friends had never heard.

With each meeting, the story of the Hoffer family vacation home emerged, piece by piece.

The family learned that when Canadian troops landed at H-Hour, the beginning of the amphibious assault, the Germans that were inside the home fired at them from a machine gun mounted on a bench and aimed outside the front window. Many of the soldiers who were not gunned down hid behind a beach wall near the home, from which they were able to regroup and expel the German troops from the house.

Many soldiers who return, Nicole Hoffer said, are surprised to find the wall gone, buried by sand over the years. The house, however, still looks mostly the same.

A summer home filled with war memories

The Hoffers have collected countless souvenirs over the years, including a cross (center) that one veteran discovered during the war. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

The Hoffers found that as veterans kept coming back over the years, more and more began to bring souvenirs for them, so many that their summer home is now effectively doubles as a museum. Their guestbook has collected hundreds – if not thousands – of signatures from veterans and their families returning to Juno Beach. One signer, Ernie Kells, even apologized for tossing grenades into their basement to flush out German troops.

Donated medals, flags, paintings and other keepsakes adorn the walls, including a cross featuring a Jesus icon whose arm had apparently been blown off while in a soldier’s pocket. The man had found the cross intact in a nearby house, and shrapnel that hit it may have saved his life. Years later, on his death bed, the man had asked his family to return the cross to the Hoffer’s home.

“In the house, you find a lot of memories,” she said.

Their guestbook is filled with hundreds of entries, including that of one soldier who tossed grenades into their cellar. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

The Hoffers eventually began hosting their own ceremony to honor Canada’s fallen soldiers. About a week before June 6, they light a paraffin lantern and leave it burning on the balcony. Then on the evening of the anniversary, bagpipers play as the lamp is tossed into the sea, while guests place flowers and crosses where the water meets the sand.

Herve Hoffer was responsible for throwing the lamp himself until his sudden death in 2017, To honor his memory, Nicole Hoffer has opened the house to even more veterans than when he was alive.

“Now there’s trips, entire buses who come and ask if we can open the house,” she said.

For the 80th anniversary of D-Day this year, Hoffer is expecting a larger crowd. Not only will there be the usual contingent of visitors to her home, but the west side of the house will open to the public for the first time since being purchased by the local government. It is hosting an exhibit featuring the testimony of French men and women who lived through D-Day as children.

Photographs of the landing at Juno Beach are displayed on the wall next to Canada House. - Joshua Berlinger/CNN

Remembering with sadness, the British D-Day veterans recall the war they saw and knew

DANICA KIRKA and KWIYEON HA

Mon, June 3, 2024

D-Day 80th Anniversary British Veterans

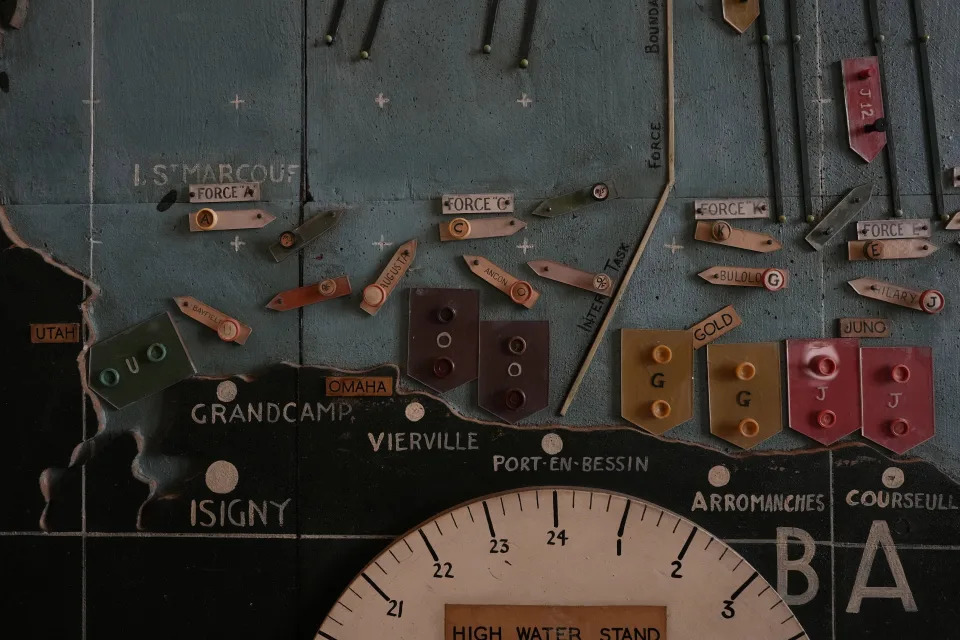

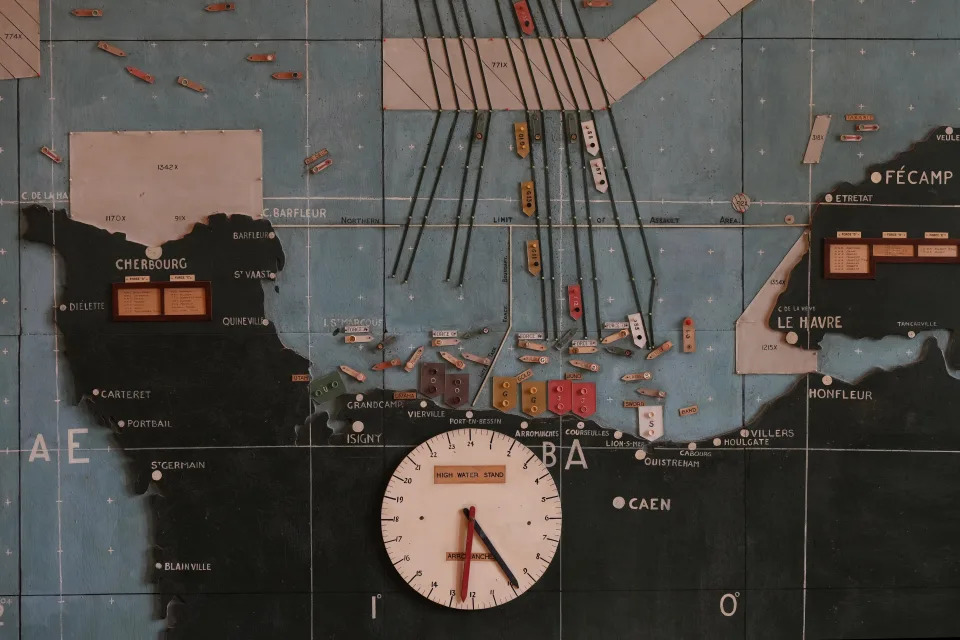

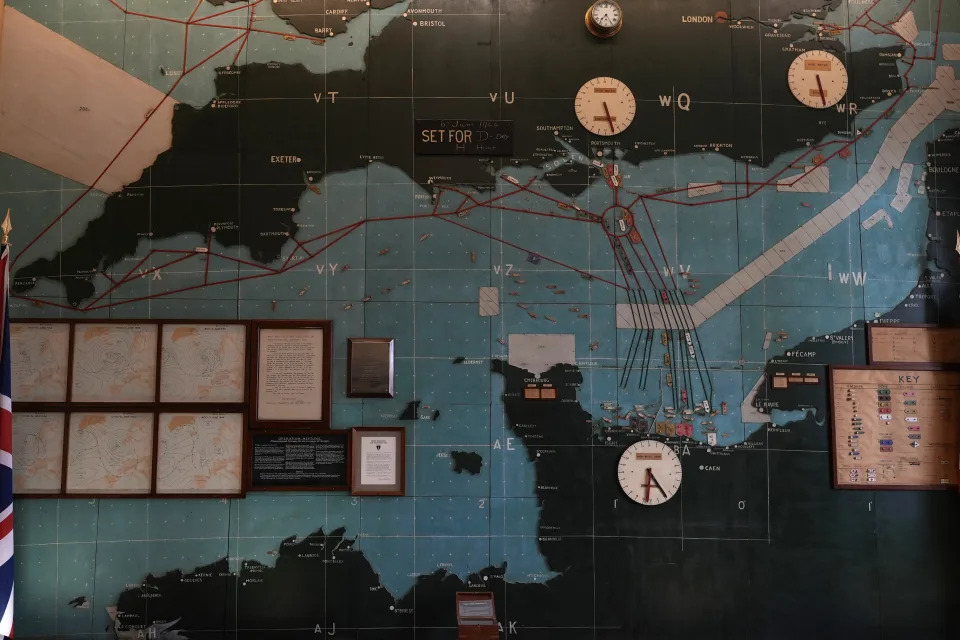

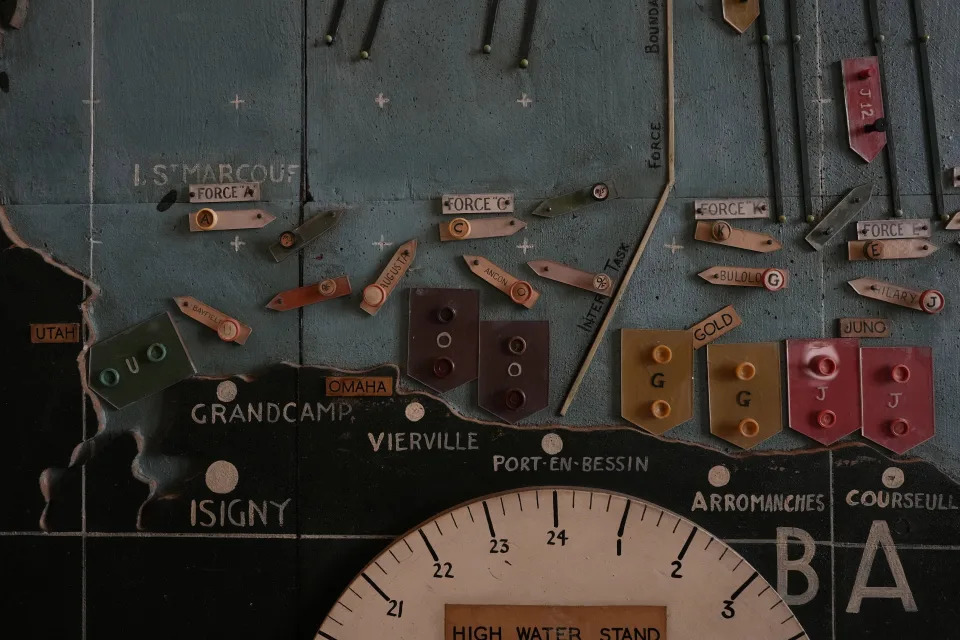

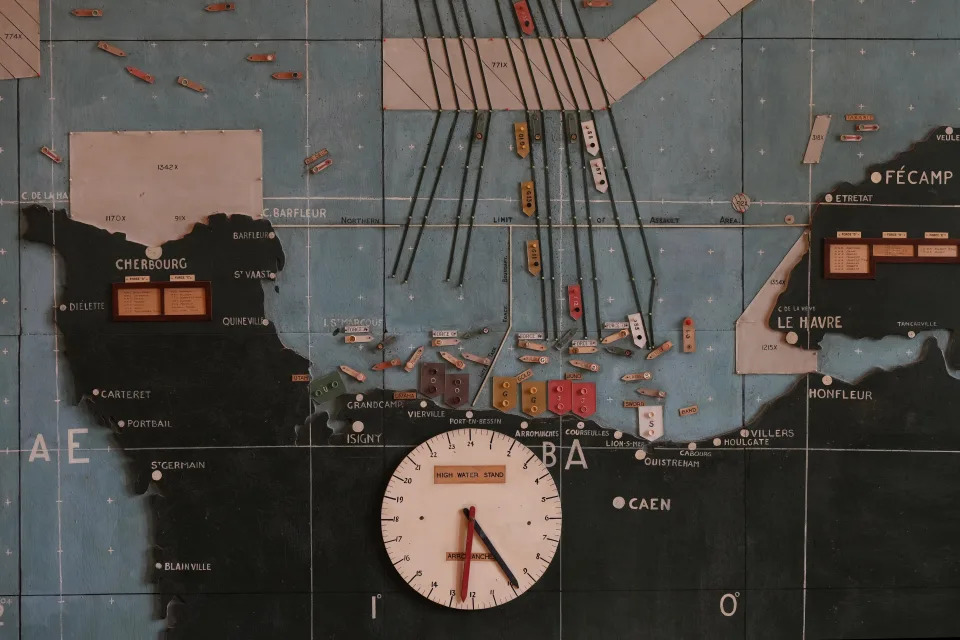

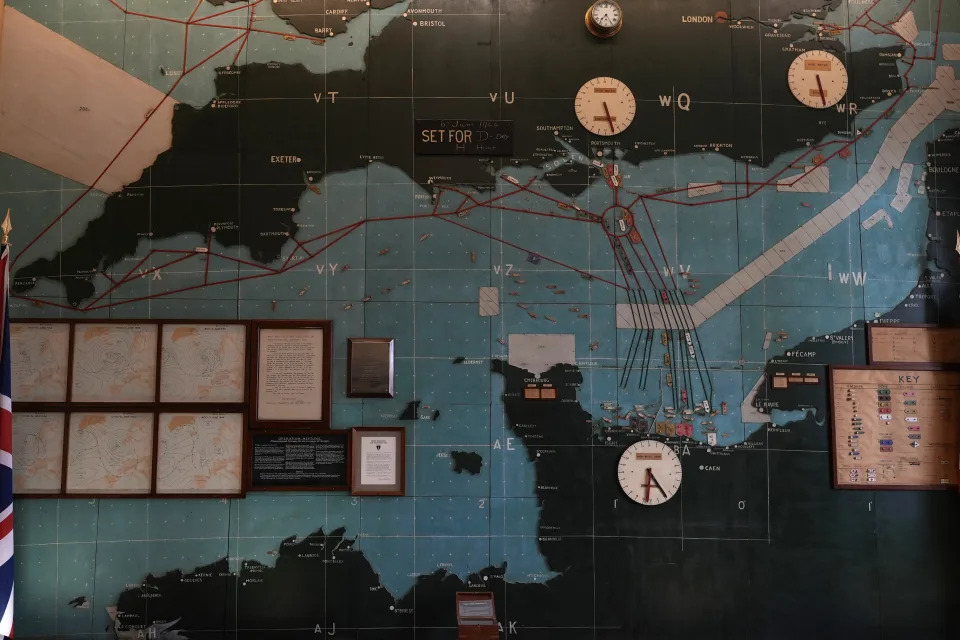

Normandy campaign veterans pose in the 'Map Room' which shows the large diagram of the D-Day invasion plans, at Southwick army base near Portsmouth, England, Monday, June 3, 2024. The map was used by Naval planners under the command of of British Admiral Bertram Ramsay. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

DANICA KIRKA and KWIYEON HA

Mon, June 3, 2024

PORTSMOUTH, England (AP) — The British D-Day veterans who gathered Monday to kick off events marking the 80th anniversary of the landings in Northern France didn’t need a calendar to remember June 6, 1944.

The events of that day remain etched on their minds, unforgettable in their horror, inexplicable in their pain.

The mood was somber as about 40 of those who took part in the operation visited Southwick House, on the south coast of England, the Allied headquarters in the lead up to the Battle of Normandy. The event, sponsored by Britain’s Ministry of Defense, came before many of the veterans travel to France for international ceremonies commemorating D-Day.

Les Underwood, 98, a Royal Navy gunner on a merchant ship that was delivering ammunition to the beaches, kept firing to protect the vessel even as he saw soldiers drown under the weight of their equipment after leaving their landing craft.

“I’ve cried many a time … sat on my own,’’ Underwood said. “I used to get flashbacks. And in those days, there was no treatment. They just said, "Your service days are over. We don’t need you no more.’’’

But the aging veterans still find the strength to speak about their experiences, because they want future generations to remember the sacrifices of those who fought and died. With even the youngest of them now nearing their 100th birthdays, they know they are running out of time.

George Chandler, 99, served aboard a British motor torpedo boat as part of a flotilla that escorted the U.S. Army assault on Omaha and Utah beaches. The history books don’t capture the horror of the battle, he said.

“Let me assure you, what you read in those silly books that have been written about D-Day are absolute crap,” Chandler said. “It’s a load of old rubbish. I was there, how can I forget it?

“It’s a very sad memory because I watched young American Rangers get shot, slaughtered. And they were young. I was 19 at the time. These kids were younger than me.”

The events of that day remain etched on their minds, unforgettable in their horror, inexplicable in their pain.

The mood was somber as about 40 of those who took part in the operation visited Southwick House, on the south coast of England, the Allied headquarters in the lead up to the Battle of Normandy. The event, sponsored by Britain’s Ministry of Defense, came before many of the veterans travel to France for international ceremonies commemorating D-Day.

Les Underwood, 98, a Royal Navy gunner on a merchant ship that was delivering ammunition to the beaches, kept firing to protect the vessel even as he saw soldiers drown under the weight of their equipment after leaving their landing craft.

“I’ve cried many a time … sat on my own,’’ Underwood said. “I used to get flashbacks. And in those days, there was no treatment. They just said, "Your service days are over. We don’t need you no more.’’’

But the aging veterans still find the strength to speak about their experiences, because they want future generations to remember the sacrifices of those who fought and died. With even the youngest of them now nearing their 100th birthdays, they know they are running out of time.

George Chandler, 99, served aboard a British motor torpedo boat as part of a flotilla that escorted the U.S. Army assault on Omaha and Utah beaches. The history books don’t capture the horror of the battle, he said.

“Let me assure you, what you read in those silly books that have been written about D-Day are absolute crap,” Chandler said. “It’s a load of old rubbish. I was there, how can I forget it?

“It’s a very sad memory because I watched young American Rangers get shot, slaughtered. And they were young. I was 19 at the time. These kids were younger than me.”

D-Day 80th Anniversary British Veterans

Normandy campaign veterans pose in the 'Map Room' which shows the large diagram of the D-Day invasion plans, at Southwick army base near Portsmouth, England, Monday, June 3, 2024. The map was used by Naval planners under the command of of British Admiral Bertram Ramsay. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

How AP covered the D-Day landings and lost photographer Bede Irvin in the battle for Normandy

VALERIE KOMOR

Updated Mon, June 3, 2024

Bede Irvin was killed July 25, 1944 near the Normandy town of Saint-Lo as he was photographing an Allied bombardment. (AP Photo/Jeremias Gonzalez)

NEW YORK (AP) — When Associated Press correspondent Don Whitehead arrived with other journalists in southern England to cover the Allies' imminent D-Day invasion of Normandy, a U.S. commander offered them a no-nonsense welcome.

“We’ll do everything we can to help you get your stories and to take care of you. If you’re wounded, we’ll put you in a hospital. If you’re killed, we’ll bury you. So don’t worry about anything," said Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Heubner of the U.S. Army 1st Infantry Division.

It was early June 1944 — just before the long-anticipated Normandy landings that ultimately liberated France from Nazi occupation and helped precipitate Nazi Germany's surrender 11 months later.

On D-Day morning, June 6, 1944, AP had reporters, artists and photographers in the air, on the choppy waters of the English Channel, in London, and at English departure ports and airfields. Veteran war correspondent Wes Gallagher — who would later run the entire Associated Press — directed AP's team from the headquarters in Portsmouth, England, of Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The greatest armada ever assembled — nearly 7,000 ships and boats, supported by more than 11,000 planes — carried almost 133,000 troops across the Channel to establish toeholds on five heavily defended beaches; they were code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword and stretched across 80 kilometers (50 miles) of Normandy coast. More than 9,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded in the first 24 hours.

Having heard on German radio that the landings had begun, Gallagher hurried to the British Ministry of Information to await the official communique. It came just before 9 a.m. with this brief instruction: “Gentlemen, you have exactly 33 minutes to prepare your dispatches.”

At precisely 9:32 a.m., the doors opened and the journalists poured out to release their reports. Gallagher’s FLASH appeared via teletype in the New York headquarters of AP just one minute later.

LONDON—EISENHOWERS HEADQUARTERS ANNOUNCES ALLIES LAND IN FRANCE.

The 1,300-word story that followed began: “Allied troops landed on the Normandy coast of France in tremendous strength by cloudy daylight today and stormed several miles inland with tanks and infantry in the grand assault which Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower called a crusade in which ‘we will accept nothing less than full victory.’”

As men on either side of him were killed, AP correspondent Roger Greene waded ashore on the eastern end of the landing front. Sheltering in a bomb crater, Greene pounded out the first AP report from the beachhead, with wind flicking sand into his typewriter keys and rattling the paper.

“Hitler’s Atlantic Wall cracked in the first hour under tempestuous Allied assault," he wrote.

On Omaha, the deadliest invasion beach, AP's Whitehead lost his bedroll and equipment and nearly his life as he landed with the 16th Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division.

“So many guys were getting killed that I stopped being afraid. I was resigned to being killed, too," he later recalled.

He witnessed German heavy machine-gun fire, mortar and artillery rounds raking landing craft and pinning down U.S. soldiers, vehicles and supplies that “began to pile up on the beach at an alarming rate.”

Whitehead never forgot the calmness of Col. George A. Taylor urging troops onward by yelling: “Gentleman, we’re being killed on the beach. Let’s go inland and be killed.”

The Battle of Normandy was underway, with Allied forces pushing off the beaches and fighting their way inland in the following days and weeks. By June 30, the Allies had landed 850,000 soldiers, nearly 150,000 vehicles and more than half a million tons of supplies.

Casualties mounted on all sides and among French civilians. By the second half of August, with Paris being liberated, more than 225,000 Allied troops had been killed, wounded or were missing. On the German side, more than 240,000 had been killed or wounded and 200,000 captured.

The dead included 33-year-old AP photographer Bede Irvin, killed July 25 near the Normandy town of Saint Lo as he was photographing an Allied bombardment that went horribly wrong, with some of the bombers mistakenly dropping their payloads on their own forces.

As well as Irvin — hit by shrapnel as he was diving for the shelter of a roadside ditch — more than 100 American soldiers were killed and almost 500 others wounded, said Ben Brands, a historian with the American Battle Monuments Commission. It manages the the Normandy American Cemetery where Irvin is buried, overlooking Omaha Beach.

On Monday, colleagues from AP’s Paris bureau, covering the 80th anniversary of the landings, laid flowers at the foot of the white stone cross on his grave. Irvin's is one of 9,387 graves in what was the first American cemetery in Europe of World War II, set up two days after D-Day.

In its September 1944 edition, AP's in-house magazine said the native of Des Moines, Iowa, had until then survived some of the worst fighting in Normandy and “had only one complaint — that he was not seeing enough action.”

In a letter after his death to one of Irvin's AP colleagues, his widow, Kathryne, poured out her sorrow. Muriel Rambert, an ABMC guide at the cemetery, read out an extract Monday at his grave, after she'd used sand from Omaha Beach to highlight Irvin's name on his headstone and planted American and French flags in front of it.

“There are so many hopes and plans between a husband and wife,” she said, reading from the letter. “Plans that won't for Bede and me ever come true.”

___

Valerie Komor is AP's director of corporate archives. Associated Press writer John Leicester in Colleville-sur-Mer, France, contributed to this report.

Muriel Rambert, interpretive guide at American Battle Monuments Commission, shows a portrait of Associated Press photographer Bede Irvin, at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France on Monday, June 3, 2024

BEFORE SAVING PRIVATE RYAN

No comments:

Post a Comment