Bay Area Reds

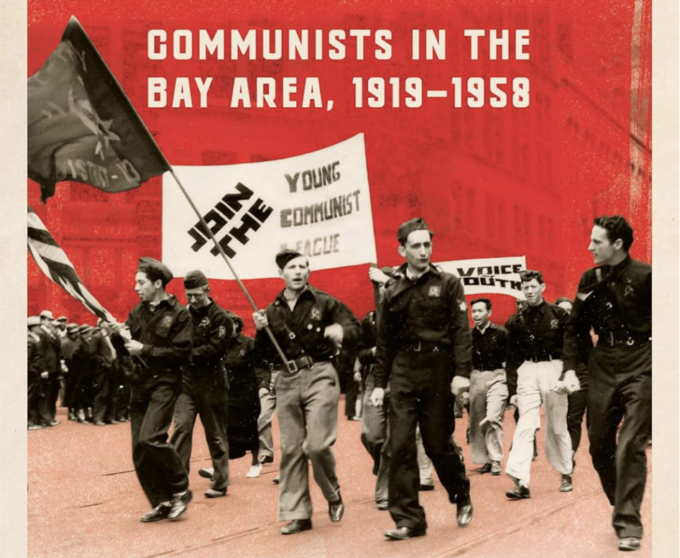

Image Source: Cover art for the book “San Francisco Reds” by Robert W. Cherny

The story of the US Left has been pretty much ups and downs, more downs than ups, something hardly surprising in world capitalism’s leading nation with a working class historically divided by race and ethnicity. Among the most startling cases is surely the California Story. Where else would a leading revolutionary of the 1880s also be a leader of the anti-Chinese movement (in San Francisco) and soon, the savant of a utopian colony in the Redwoods? Where else would a millionaire socialist, that is to say Gaylord Wilshire, publish a popular leftwing magazine and get a major city street named after him? And so on.

The California Socialist Party of pre-1920 days elected mayors, guided at least some craft unions, had quite a following among displaced Yankees and a scattering of ethnic groups. The rough conditions of what would one day become known as the Left Coast meanwhile prompted IWW-like, semi-anarchist labor activism. It is a bitter irony that Communists, the successor to all this, could not find their way until the middle 1930s, and that a major portion of the early failure falls upon their own blunders and those of Communists far away. In the end, they built quite a movement but not much of a Communist Party proper. There may be a moral here.

Robert Charny’s new book,  San Franciso Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919-1958, is narrowly cast around the CP structure, membership, tactics and projects. If the framework of this wonderful study leaves out much, it nevertheless offers insights in abundance. Research on personalities, some of it from the Moscow files recovered only in recent decades, is rich and dense. He offers a close look at people widely known, including LA leader Dorothy Healy and not-quite-communist ILWU champion Harry Bridges, about whom Cherny’s own biography is an outstanding contribution. He also offers a view of many Communists hardly known at all.

San Franciso Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919-1958, is narrowly cast around the CP structure, membership, tactics and projects. If the framework of this wonderful study leaves out much, it nevertheless offers insights in abundance. Research on personalities, some of it from the Moscow files recovered only in recent decades, is rich and dense. He offers a close look at people widely known, including LA leader Dorothy Healy and not-quite-communist ILWU champion Harry Bridges, about whom Cherny’s own biography is an outstanding contribution. He also offers a view of many Communists hardly known at all.

In doing so, he strays from the Bay Area of the book’s title across California, often usefully, albeit sometimes arguably stretching the narrative too thin. There is or could be so much more to say about the State party. Communist Hollywoodites, actors, writers and others once the source of damning headlines, play no role here, for instance. Missed here, most of all, is the way in which the Popular Front enabled a movement to grow far beyond its presumed natural borders.

One large insight hides behind the text and is not quite properly Charney’s subject at all: how different things were for the Left, East of California. Repression hit everywhere during the First World War. The Wobblies were practically if not entirely wiped out by violent raids on their headquarters and arrests of their leaders. Socialist newspapers were banned by the neat trick of removing their mailing permits. That some erstwhile socialists joined in the global crusade of Woodrow Wilson, all but urging the repression of their erstwhile comrades, did not help matters.

By contrast, in mostly but not entirely urban parts of the East and parts of the midwest, immigrant groups especially but not only from Eastern and Southern Europe would bounce back strong in the 1920s, their newspapers and networks transferred from Socialist to Communist without much disruption. In factory neighborhoods where blue collar populations walked to work, the ethnic clubs built support through services, family entertainment and hopes for unionization. In New York but not only there, Leftwing Yiddish culture in the golden age of “Yiddish Broadway” prompted a vast network of leftish activities, speaking or singing to a population facing severe anti-Semitism. Calfornia was not so lucky.

The Syndicalism Acts of California in 1921, aimed at an IWW already repressed but with capabilities in agriculture, also hit the new Communist movement hard. The small collections of Communists, barely emerging from the 1919 spit in the Socialist Party, limped into the internecine wars of competing communist factions (not to mention the work of Bureau of Investigation operatives), and damaged themselves badly. The further sectarian impulse to separate Communists from the “merely” but often popular reformist socialists successfully separated them from a populistic sentiment symbolized in radical novelist Upton Sinclair. Later on, that bitter opposition cost them dearly.

From another angle, the New York leadership of the Communist Party repeated the lack of insight shown by the leadership of the earlier Socialist Party, from their Chicago headquarters, and for that matter the New Left, Trotskyist and Maoist small-scale organizations later on. None could quite grasp the need for different approaches and the vast political opportunities in the complex and contradictory California scene. All expressed degrees of frustration, as if California leftists just couldn’t see what needed to be done.

Cherny beautifully explains the flawed, worse than flawed, internal logic of the CP toward its California faithful in the 1920s to the early 1930s and this takes up the first three chapters of the book. They could not win for losing, and every new opportunty seemed to present a lost opportunity. An elderly Communist explained to me, in the later 1970s, that after the Trotskyist and Lovestoneite (“Left” and “Right” so called deviations) had been expelled at the end of the 1920s, factionalism repeated itself as personality versus personality within the leadership, and this was abundantly clear when local and regional Communists tried to climb back from failed efforts.

In the California case, it was possible to rally large numbers behind Robert La Follette in 1924, but the national leaders went a different direction. By the early 1930s, California Communists launched major defense campaigns for imprisoned unionists, drawing in young actor James Cagney among others, but could not manage to create a “front.” Any more than they hold onto the Mexican-American agricultural workers, who had last supported the Wobbly efforts to organize them.

By mid-book, Cherny moves onward to the Popular Front years or rather to 1934, anticipating the Party’s golden age. The San Francisco “General” Strike, which effectively brought the Longshoremen from relative isolation into a union of great influence and Harry Bridges from obscurity to global fame, marked a turn in more ways than Communists abroad could easily grasp. Bridges himself sturdily denied affiliation with the CP, and it was as an influence within the ILWU (some would say control, others would say that local leadership could never be categorized in this fashion) that the Left moved forward. Membership did not surge forward in the expected European Communist fashion. Men and women in the Bay Area and far beyond, buillding the ILWU all the way to Canada and Hawaii, would fight to the point of laying down their lives and yet feel no urge to join (more likely, to stay in) a Communist organization.

That the same 1934 marked the CP’s running a candidate against Upton Sinclair marked a foolishness not repeated until 1948, when the CP seemed to have little room to manuever. In between, especially through the unions but also in related campaigns of all kinds, including the brave support of racial minorities, the Party filled in many of its gaps of influence on labor and liberalism. Characteristic but not much discussed here is the Peoples Daily World, more lively, with better prose and illustrations, than the Daily Worker back in New York. Or consider the National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards, the most openly gay union in the CIO and the most obviously Red, allied closely to the ILWU. Nothing in global Communist movements could have predicted this.

Or for that matter, the Communist chicken-farmers around Petaluma, north of San Francisco, rushing to help striking Mexican-American workers and risking their own livelihoods. As repression struck, they fell back upon their own Yiddish-based communal culture of music and literature, recalling the ghetto struggles a world and half a century away in Eastern Europe.

Leftwing Californians had some great human material to work with, including a dedicated cadre of screenwriters, a handful of them future Oscar winners, but also a wide-ranging and often unexpected cadre of members and supporters. A section of the middle class, Yankee and Jewish, had mostly held back from the CP until the Popular Front and then entered full flush. Fundraisers could be held in Charlie Chaplin’s mansion with Lucille Ball welcoming guests including plenty of high profile actors, labor leaders and liberal politicians. We can wince today at Ring Lardner’s quip that the CP had the smartest intellectuals and the prettiest girls in Hollywood, noting the “girls” were smart and active and given to asserting their own rights.

Cherny points to the repressive power of California conservaties and the State taking swift action at any sign of weakness. Following years of anti-fascist agitation, the CP entered isolationism 1939-41 and lost a lot of its support—regaining most of it, and more, after Pearl Harbor. But HUAC investigations, already begun in the “Pact Period,” would be back soon and more deadly than ever. That the Congressional “investigating” comittees were openly anti-Semitic helped discredit reactionary claims in advance, but future California politicians, greatly aided by the FBI (Ronald Reagan’s own brother was an agent), had already set a trap that Communists and their allies could hardly evade.

For my taste, writing as a social historian, the Party history pre-1945 is rather too thin in seven chapters, the history 1945-58 arguably too thick in the final two. So much social history exists in the former, so little in the latter, especially after 1948, when the California CP, like its national counterpart, pretty much falls apart. And yet even here, the ILWU as anti-racist unionism across California, the return of Communist veterans (perhaps no longer party members) to assisting the organization of farm workers, and the role of Communist-influenced Democrats in the California state legislature as well as local offices—all this “counted,” if not in CP terms.

Cherny is at his strongest when he offers insights from the personal angle, much about what leaving a hectic political life for a personal life meant. A recognition that the glorious era of the CP was really over, certainly, but also a sense, insufficiently expressed here, that the country had changed. The unionized part of working class had established a certain status, at least for a generation. Consumer goods, inexpensive automobiles, even blue collar suburbs could allow depoliticized leftwingers feel as if they could live “normal” lives, especially when FBI harassment had done its career-worst and left them alone.

The links with the movements of the 1960s-70s might have been developed suggestively, although this could logically be part of another book. A curious bit of research into the youth culture scene of LA during the 1960s has turned up nightclubs owned by savvy former CPers. Others of the fading generations hit the streets all the way up to Santa Cruz, where hundreds relocated in the 1970s-80s, leafletting and agitating for political and environmental causes as long as their legs could hold them.

Some of the many oldtimers still around, Japanese-American Communist Karl Yonenda most notably, became the subject of great admiration, considered kindly grandfathers and grandmoothers to the new generation, offering contacts, sympathetic advice and assistance. Another might become the documentary photographer of the Vietnam Day Committee in San Francisco, Harvey Richards, capturing demonstrations when the commercial press had not caught up (or not been allowed to catch up) with the new mass movements. Perhaps more than any other sector, aged Communists of color met up successfully with young activists in every possible venue, explaining things that had never been well understood within the “white” Left.

All that said: a good book, a necessary book.

No comments:

Post a Comment