Applying the moral wages of Watergate 50 years on

What lessons might we draw from that scandal for our political dilemma today?

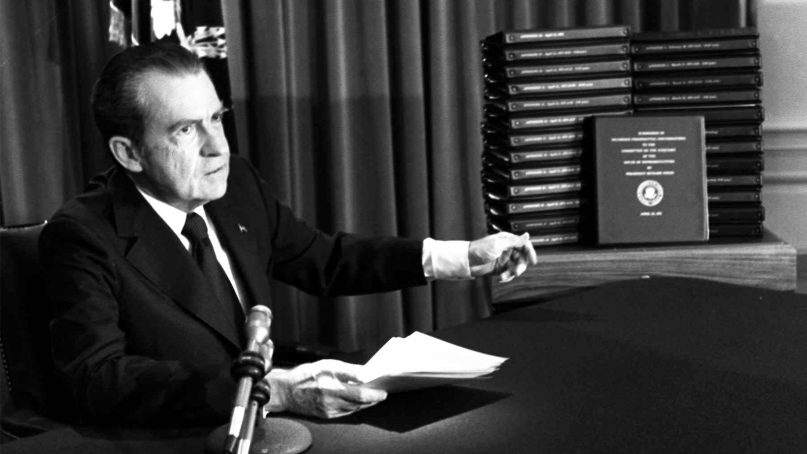

President Richard Nixon gestures toward transcripts of White House tapes after announcing he would turn them over to House impeachment investigators and make them public in April of 1974. (AP Photo)

August 22, 2024

By Lovett H. Weems Jr.

(RNS) — This summer we remember a political tragedy from 50 years ago that many at the time considered the greatest constitutional crisis since the Civil War. What became known as the Watergate scandal began a series of questionable and illegal actions during the Richard Nixon administration that first came to light with the arrest of five burglars at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington in June 1972.

Evidence would reveal that the burglary, at a hotel and office complex called the Watergate, was part of a larger spying and sabotage component of the Nixon reelection effort, financed by campaign funds.

President Nixon tried to stop the discovery of the full scope of this activity, telling his aides to order the FBI to limit its inquiry. But in July of 1973, a secret White House recording system was uncovered and when the relevant tapes were released by court order, the extent of Nixon’s involvement was revealed. Months of Senate hearings, followed by an impeachment inquiry by the House Judiciary Committee, led to three articles of impeachment in July 1974.

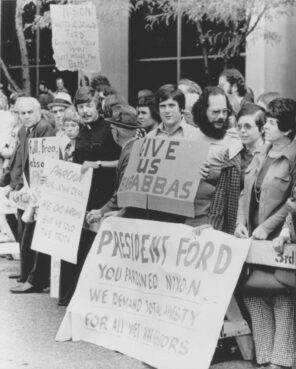

With revelations from the last tapes delivered on Aug. 5 of that year, Nixon’s support in Congress vanished. Nixon announced his resignation on Aug. 8 and was succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford, who pardoned Nixon on Sept. 8, 1974.

A crowd outside a Pittsburgh hotel where President Gerald Ford was addressing a transportation conference holds signs protesting his decision to grant a pardon to former President Richard Nixon for any crimes he may have committed while chief executive. (RNS archive photo. Photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society)

Throughout U.S. history, political scandals have exposed corruption and misdeeds in nearly every presidential administration. Something different took place, however, in Watergate. More was at stake than isolated conflicts of interest or political dirty tricks. The very processes of our nation and the foundation on which the country stands were at stake. The tools of government designed for use against national enemies were used against U.S. citizens, and instruments of the intelligence community were used against another branch of government to stop an investigation.

At the time, it was common to hear that partisan politics were behind the outcries, or that much was being made over little more than run-of-the-mill political chicanery. But as records and transcripts from the White House tapes continued to come out, it became clear that it was not politics or the press that brought down a president. It was criminal evidence.

What can people of faith learn from this chapter in our history?

One thing missing through the course of the Watergate saga was a sense that the participants felt any moral accountability. Jeb Stuart Magruder, a Nixon aide who went to jail for his role in the scandal and later became a Presbyterian pastor, told Watergate Judge John Sirica, “Somewhere between my ambitions and my ideals I lost my ethical compass.”

One of the most prominent witnesses at the Senate hearings was White House counsel John W. Dean, who said, “Slowly, steadily, I would climb toward the moral abyss of the President’s inner circle until I finally fell into it, thinking I had made it to the top just as I began to realize I had actually touched bottom.” He aptly titled his account of those years “Blind Ambition.”

But Watergate also provides examples that new life can come to those who repent. The Boston Globe wrote at the time about Charles Colson, a Nixon aide willing to do virtually anything for his boss, “If Mr. Colson can repent his sins, there just has to be hope for everybody.” Yes, that is truly what many people of faith believe. There is hope for everyone. The new life and purpose found by many, though not all, of the Watergate participants bears witness to this reality.

Billy Graham was the presidential “court evangelical” long before historian John Fea coined it in reference to Donald Trump’s advisory committee of Christians. Graham had benefited from — and been used by — presidents well before Nixon. In Watergate, Graham faced the greatest crisis of his own credibility because of his staunch defense of Nixon. In one afternoon, Graham read all of the transcripts published by The New York Times and became “physically, retchingly sick.” As he examined his own soul, he said, “I had to say with John Wesley, ‘I looked at my soul and it looked like hell.’”

President Richard Nixon, right, and Billy Graham bow their heads in prayer during the president’s visit to the Billy Graham East Tennessee Crusade at Knoxville, Tenn., in 1970. (RNS archive photo)

One lesson that came from Watergate was a new appreciation for persons of unshakable integrity, a virtue our culture often regards as less important than superficial success or status. Why did so many involved choose not to speak out or simply resign? Had they no lively sense of right and wrong? What if once in those exchanges in the released transcripts somebody had said, “This is wrong” or simply asked, “Is this right?” instead of “Can we get away with it?” Judge Sirica was correct to observe that just a little honesty and character would have stopped this awful thing at the very beginning.

If there are any heroes in Watergate, they are found in people who simply did their duty in the way they sensed to be right: Frank Wills, a night watchman at the Watergate who was so good at his job that he spotted tape the burglars had used to hold open a door. Sam Ervin, a “country lawyer” senator from North Carolina, who could quote from both the Constitution and the Bible “by heart.” Elliot Richardson and William Ruckelshaus, an attorney general and deputy attorney general who resigned rather than carry out a presidential order to fire the special prosecutor on the case. Young reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, along with their courageous editor Ben Bradlee and publisher Katharine Graham, exposed what too many were attempting to hide. These are among those we may still remember and honor.

When President Nixon resigned in August 1974, I was a pastor in Mississippi. I wrote these words to my congregation: “Seldom do we value or even try to understand the person who acts on the basis of conscience if we personally disagree with his or her action. How wonderful it would be if we could really believe that the sun shines on nothing more beautiful or majestic than a person of integrity and principle. If this were the case, then we would reserve our highest honors for those who say with Job, ‘Till I die, I will not violate my integrity.’”

RELATED: The Trumpian breach of faith

What might all this mean for our political dilemma today? The actions and language of some political figures today make the villains of Watergate seem almost moral by comparison — their attempted cover-up at least acknowledged a sense of guilt. Bipartisan action when confronted with evident corruption appears to belong to another time.

Perhaps we would do well to remember some words from former New York Times executive editor Turner Catledge about Nixon after Watergate, “We should have paid more attention to the kind of man he was.”

That’s something about which people of faith have traditionally cared deeply.

(Lovett H. Weems Jr. is professor emeritus of church leadership at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington and senior consultant at the seminary’s Lewis Center for Church Leadership. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

No comments:

Post a Comment