The end of Venezuela’s Bolivarian process? An interview with community activist Gerardo Rojas

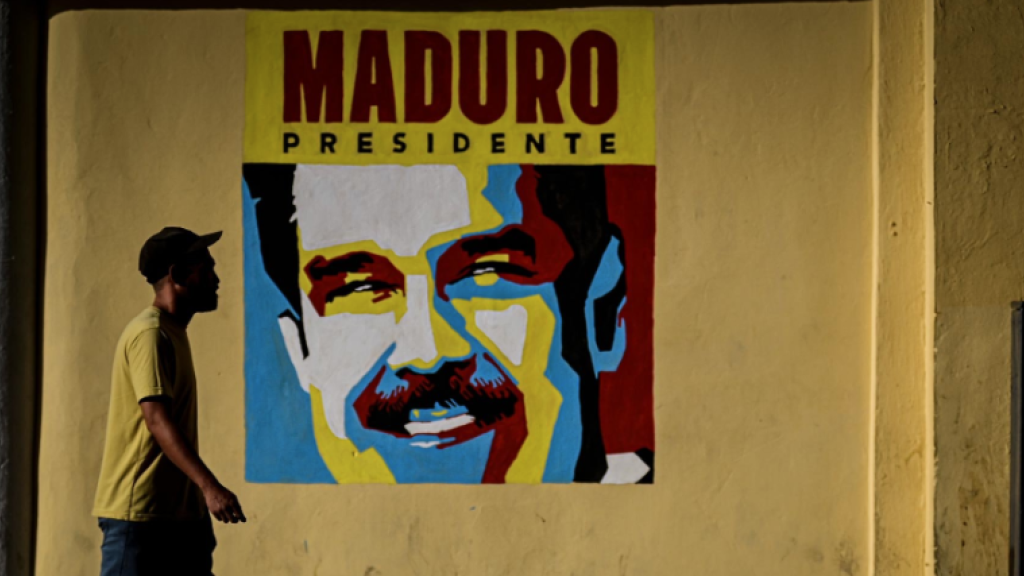

Gerardo Rojas is a community organiser in Barquisimeto, Lara, and a Chavista activist, a reference to the political movement of the working-class poor that backed former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. A founder of the alternative media collective Voces Urgentes (Urgent Voices) in 2002, he participated in one of the first urban communes, Comuna Socialista Ataroa (2007). Rojas was a vice-minister in the Ministry of Communes in 2015 and is part of the communication, education and political activism collective Tatuy TV, though the opinions expressed in this interview are his own. Speaking to Federico Fuentes for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, Rojas discusses why it is so important that the full results of the July 28 presidential election be published, the current state of community organising in the country and why we might be witnessing the Nicolas Maduro government’s final break with the Bolivarian process of radical change initiated by Chávez.

What are your thoughts on the fact the National Electoral Council (CNE) has still not published the final results more than a month after the presidential election?

To us it is crazy. This is the first time in Venezuela’s recent history that, 38 days after an election, we still do not have verifiable results broken down by polling booths. [This interview was completed on September 4 and, at the time of publication, no results have been released.] Traditionally, on election night or at the very latest the next day, we would go to the CNE webpage and look at the results, booth by booth, to verify what had occurred in our community and compare the results with the previous election. We did this because we believe that participation and legitimacy is key and fundamental to any democracy, and should not only be left to political parties but involve the community. That was our tradition: meetings to evaluate, compare results between polling centres and draw up a balance sheet. These results are basic ingredients for a vibrant and active democracy, which is the democracy we defend. As important as the total results are, they do not tell you everything you need to know about an election.

Publishing the results is not just a legal obligation, it is a basic principle of the Bolivarian Revolution. In an editorial that we published as Tatuy TV, we said that [the results] have always been our instrument of struggle and defence in the community, including in those places where [the Chavista movement] did not win, because in some working-class areas the vote was sometimes either very close or we lost. They allowed us to converse, discuss and reactivate. If we have learnt anything from doing community organising it is that communities are broad and diverse, and that community assemblies are where we should all come together, regardless of political differences. That was a clear part of Chávez’s political thinking: not to see diversity and differences within a community as the enemy, so that neighbours could live together in peace. Deconstructing differences was only needed when they became obstacles for community development. That is why publishing the results is an obligation to society, because it is a means to help unblock the current political situation, not only from above but from below. Used this way, they can be an instrument for rebuilding the social-political fabric of our country.

We must also never forget that we are not in a normal situation. Our election was held in circumstances that do not exist in any other country. It has to be said: Venezuela is a country under permanent assault from the US empire. We are the victims of illegal mechanisms [such as sanctions] that impact on our country’s income. There is no doubt that we face permanent attacks against the country’s different institutions. Also, in various communities there were attacks on Chavista community leaders in the days after the elections. Sadly, two grassroots activists were assassinated. Unfortunately, this is not new; similar events have occurred during previous moments of political tensions.

But I am one of those who believes that none of this is an excuse to not publish detailed election results. In part because it could unblock current political tensions, as it would allow everyone to assume their responsibility amid the complex moment the country is passing through. That is essential. That is why, for me, there is no reason to have still not published the results. There is no technical reason not to have done this after so many days. A PDF uploaded anywhere could be a start. When the CNE had problems with its website in other elections, it set up a mirror site and published information there. There is simply no technical explanation for why we do not have this information.

How do you evaluate the protests that kicked off after the CNE announced its initial results?

Some say all the protests were peaceful, others say they were all violent. I think there were both types but that the majority, more than protests, were mobilisations in working-class sectors by those who assumed they [the opposition] had won. This is normal in many parts of the world, and above all here. That is not to deny that there were protests in various parts of the country, both peaceful and violent, including in working-class sectors. I live in a working-class sector in Barquisimeto. Here the people organised a cavalcade in celebration of what they perceived as their victory [against the government]. There were also other actions that were clearly not celebrations. For example, a supermarket was looted near where I live. Thankfully, those types of actions were the minority, even if some of them were very grave, such as the arson attacks on institutions or the very violent attack on a community radio station in Lara state, where people suffered tremendous beatings and threats of being burnt alive.

However, generally speaking, the number of announced arrests did not correlate to the protests that occurred in the days after the election. There is no clear or direct proportionality between the violence and number of arrests. We have lived through some very difficult moments of political violence. And violent acts did occur on July 29 that, of course, require a response from the state to ensure they are not repeated. But I do not see any correlation in terms of the numbers of arrests. Moreover, as we said in the editorial, if we say that there were 2000 terrorists or fascists involved in street actions, then that represents a defeat for the Bolivarian Revolution. It would mean we have been unable to dismantle a terrible form of doing politics, such as fascism, which is present in some sectors of the opposition.

I would also add that the extreme right, which is part of the opposition and receives direct support from the US empire and its allies internationally, sought to camouflage its discourse by shifting towards the political centre. In reality, they are not a democratic option, nor any guarantee for restoring lost rights. Their violent and conspiratorial actions are partly to blame for our situation, with all the grave consequences this means not just for the country but in terms of the kind of necessary opposition Chávez always clamoured for. That said, they have been able to capitalise on the weariness and discontent that exists in our society after so many difficult years. It is vital that we correctly understand this fact; I do not believe its support is programmatic or ideological. We must take this into consideration in terms of developing a politics for the majority today.

What needs to be done to begin resolving the deadlock?

First, present the results and verify them. That is essential. And if Maduro’s victory is confirmed, ensure the results are respected. But if the numbers are correct, and 43% voted for the opposition candidate, then we must take this as our starting point. That is important because the government’s discourse has labelled everyone who voted against it as being tied to criminal elements or under the influence of right-wing propaganda and social media, which of course is a factor. But if you say that — according to your own numbers — almost half the country falls into these categories, then we need to find ways to break this deadlock by generating credible spaces for debate and openness, rather than criminalising differences. We need to publish results, verify them, open spaces for dialogue and neutralise violence while respecting human rights and the mechanisms contained in the Bolivarian constitution. That is the basic minimum we should be asking for — which, moreover, is nothing more than the norm and tradition of the Bolivarian Revolution.

And if the results are not published?

Thirty eight days have passed by without the results being published and, at times, it seems they never will. The government’s discourse in the past week is that what happened happened; that we just need to turn the page because we need to focus on the economy and Christmas will be starting in October. They are basically saying: why are we still talking about the elections if that is old news? This position is causing serious damage. Among other things, if anything defined the Bolivarian Revolution and above all Chávez, it was the basic principle of constructing democratic hegemony, of broadening our support base by convincing others. “Convince” was a key word in Chávez’s speeches, and you cannot convince others by simply asking them to have faith in you; you need explanations and arguments.

If you cannot convince others, then you cannot expand your support base and exercise democratic hegemony. You might be able to construct hegemony using other mechanisms such as coercion, but for us that is not what the Bolivarian Revolution was about. I am not saying you need to convince the ultra-right, we know that is very difficult. The issue is making sure there are no lingering doubts among the grassroot activists, that the neighbour who lives next to the local leader of the UBCh [Hugo Chávez Battle Unit, the local unit of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, PSUV] does not harbour lingering doubts. What I look at, beyond the dispute occurring from above — which of course is crucial — is what we need to do in the community. How can we turn up to an assembly and speak about participatory and protagonist democracy if we cannot even verify electoral results when people express doubts? That is key in terms of the social fabric. Rebuilding community is crucial after so many years of economic and social difficulties. I am not talking about a political party — anyone who wants to be active in any party should have this right respected. I am talking about rebuilding the capacities of society to defend itself, to come together to transform itself from below, always within the logic of a socialist society in which communities uniting is fundamental for a real democracy that is not just based on voting every four, five, six years.

I would say convincing others is fundamental. If that does not occur, you undercut the possibility of winning over the majority to your project — which means defeat. For the Bolivarian Revolution, winning the majority has meant having clear popular support for our project. That was the type of hegemony Chávez built. But by seeking to build a new historic bloc of classes today in which, as Maduro says, the capitalists play an important role, you stop seeing the people as key. Yet this was key to the Chavista project and the manner in which we built support. That is why we finished our editorial by saying this is not just about democracy, which is of course fundamental, but the very possibility of building a political project like Chavismo on its original motivating principles: respect for sovereignty, radical democracy, historic reconstruction of working-class memory, fight against corruption. Those are the basic things that have united us since the start of the Bolivarian process.

I would like to turn to one of these motivating principles — radical democracy — to get a sense of what has happened in the country since Chávez passed away in 2013. Just before he died, Chávez underlined the importance of the communes as a means for building radical democracy. Why are the communes so important?

If we trace the development of Chávez’s thinking, democracy is among the strategic guiding principles. Chàvez’s Blue Book, which was written in 1990, was circulated among soldiers and civilians who participated in the 1992 military-civilian rebellion. In it he describes almost verbatim a communal council, [the grassroots building blocks of the communes] in which communities make decisions for themselves, which the government started promoting in 2006; that is, 16 years later. The Bolivarian Constitution [adopted by referendum in 1999 after a process of popular consultations] talks about participatory and protagónica [protagonistic or self-reliant] democracy, in which it is not just a question of participating but of being a protagonist. And if you then go to Chávez's 2012 speech — known as Strike at the Helm — you will find a strategic continuity in terms of democracy. So, if we closely follow Chávez’s strategic thought, we can see that he maintained a consistent line in terms of building democracy from the communities.

In one speech, at an event, I think, to enact the constitution, Chávez explicitly said this was not the time for direct democracy; so it was clear that he was at least clearly thinking about this back then in terms of a proposal, a project, a political strategy. Then, when he launched the communal councils, he said at an event: now is the time for direct democracy. Obviously, he had to accumulate forces, take it step-by-step, advance, retreat, until the communal councils came about. This led to important advances, which were halted by the defeat [in a national referendum] of proposed constitutional reforms [aimed at deepening the Bolivarian Revolution] in 2007.

This defeat meant having to rethink the issue of communal democracy in the face of the direct and open attacks by the opposition, but also from an important section of existing Chavismo and the institutions. That is why Strike at the Helm includes very harsh self-criticism, asking: Where are the communes? What has happened? How is it possible that we have laws, resources, institutions, but they are not working? Well, this was because there has always been a fight within the revolution over this strategy. The communitarian, the communal in the broader sense of the term, was from the start a point of tension, not just with the opposition but also within Chavismo. It is unfair to say that everything to do with communal democracy was going smoothly until Maduro came along; we have to recognise that there were also problems under Chávez, otherwise we would never have had such a public act of self-criticism as the Strike at the Helm speech.

That is why, from the first moment, Chávez maintained a harsh internal criticism of the communal question. Deep down, this had to do with the question of building popular participation and democratic hegemony. Almost as if prophesying, Chávez said in 2004: “We have to remember, brothers and sisters, that [traditional social democratic party] Democratic Action once had as much as 70% electoral support and leaders capable of bringing the masses with them. It could mobilise the masses. But I think this year marks the end of that party, it is now simply a rotten husk; it is not just hollow but rotten. That is our future. If we do not change, our parties will end up just the same. Because there is no magic formula: either we have popular support and we increase it through participation and by attending to the people and loving the people, not just in words but in deeds, or we do not and our destiny shall be political death. Write it down! Because that is what will happen.”

I think that is the fundamental key to Chávez, understanding that profound, revolutionary change comes through building a fully-rounded democracy, where real power is in the hands of the people.

That is why the communes have to be viewed in the broader context of participation. This is regardless of the fact that we still have some issues that need to be further developed, such as how to combine territorial organising with sectorial organising, the different levels of self-government, the transference of powers, etc. That is why the commune is important: it is a space from which socialism comes alive. If we are unable to build spaces of self-government, where people living in that area can come to agreements, beyond any differences they may have, in order to change their concrete reality, it will be difficult to develop humans capable of collectively defending their territory and improving their conditions, both locally and nationally.

On the contrary, we will end up consolidating ideas that are now gaining a lot of traction: that what matters is individually resolving everyday problems and forgetting about politics. If we do not have communities armed with legal and political instruments and concrete experiences in conflict resolution, in working out priorities, in carrying out projects for themselves, it will be very difficult to build the fully-rounded democracy Chávez proposed: an integral, socialist democracy, not just in terms of political democracy, but social, cultural and economic democracy. If we are not talking about economic democracy, then we have a false democracy.

What is the current state of the communes?

Unfortunately, they are very weak in terms of participation, according to figures from the Ministry of Communes. Data on its website indicates that last year, only 20% of [the 3641 registered] communes had registered their Communal Parliament. That means the figure for other bodies, such as the executive, the economics committee, the planning committee, all those other structures generated by this space of self-government, is even less.

This has its explanation. These have not been easy years economically or politically, partly because of the sanctions and the political attacks against the government. There are also the consequences of the emigration [of millions of people] in recent years and governmental errors, as well as corruption. All of this directly undermines the possibility of rebuilding community. When the economic crisis was really bad and people had to dedicate themselves to ensuring their next meal or resolving essential needs, this caused problems in terms of thinking about community. Moreso when everything pointed towards individual solutions — which, unfortunately, were reaffirmed by the president when he spoke about entrepreneurship. The promotion of entrepreneurship clashes directly with community; it prioritises self-exploitation as a way out of the crisis, in which the other is seen as someone you can buy or sell to, rather than turning to collective labour, in which needs are resolved collectively. So, there are various factors that have helped undermine community.

But we also have to say that the government entrenched itself as a means of defence in the face of these harsh attacks. This had certain consequences in terms of dealing with the crisis caused by the collapse in economic growth and oil production, and the economic blockade, above all from 2016-17 onwards. A very obvious internal dispute occurred during those years over the way forward. The result was an integral shift in both economic and political terms. It was a gradual but ongoing shift. There was a readjustment in terms of the new historic bloc of classes — using the president’s words, not at the time but in more recent years — where capitalists have been positioned as an important factor of revolutionary politics. Of course that entailed an integral reconfiguration of government policies. At that time, the communal economy, although still weak, could have been developed as a pathway out of the crisis, even complementing the government’s work with the capitalists. But much of the means of productions that were in state hands were not transferred to workers or communities; instead they ended up in the hands of capitalists via “Strategic Alliances”, of which little information was made public.

At the same time, the idea that “in a besieged fortress, all dissent is treason” became dominant. This led to closing ranks in defence of the government. But when you close ranks to defend yourself, the next logical step is to continue closing yourself off. And when you assume that closing yourself off is the best defence strategy, you cut yourself off from an important part of the community, of society — and with that the possibility of constructing democratic hegemony. In the hardest years, the state basically disappeared in large parts of the national territory. Outside of Caracas — where things were not as affected, although they did affect the poor — there were entire communities with no services or formal presence of any state institution. The decision was taken that, given the lack of resources and capacity, the state had to retreat from a large part of the national territory.

In that period we saw the emergence of more hybrid forms of organisations. The community assemblies of the communal councils were relegated in favour of CLAPs [Local Committees for Supply and Production], which the government began promoting in 2016. These were jointly organised by state institutions, local PSUV leaders and sections of the community to resolve the issue of national food distribution. CLAPs were very useful in what was a difficult period for the country, and continue to contribute. But they served to displace the food committees, which were the obvious candidate for this role as they had been elected by the communal council precisely for that type of task.

There were also tensions around this issue under Chávez, which is why, on more than one occasion, he demanded respect for the autonomy of the communal councils and communes. But we can say that the shift in terms of official government policy around participation began with the CLAPs. These were the first device used to gradually relegate community assemblies, even if in many places they co-existed, though tensions between the two was clear in some.

A further step in this direction was take in 2019 when, in clear violation of the Laws of Popular Power, the Ministry of the Communes issued a call to form the “Platform of Revolutionary Forces” to elect new vocerías [spokespersons or delegates] in each communal council and commune using “ first, second and third degree delegated methods of voting” [rather than via community assemblies]. This process was named the “Communal Offensive 2019” and was initiated as a response “to the reality and the priority of the historic moment we are passing through.” The argument commonly used to justify this shift was that communal councils and communes could not fall into the hands of the opposition, when the objective had always been that they remain in the hands of the people, regardless of their political inclinations.

They were elected in this manner for various consecutive terms. Then came the pandemic which made holding assemblies impossible. It was not like this everywhere; where the community was strong, they ensured that the Laws of Popular Power were respected. In the past few years, the Ministry of Communes has once again begun calling for assemblies to be held in communities to reelect communal councils. Perhaps that is why, in comparison with the communes, 72.5% of communal councils have had elections for delegates.

Without doubt this is good news, and could rekindle important efforts in this area if these elections led to a genuine regeneration of delegates and are not just simply administrative processes. In any case, community participation does not have the weight today it once had, particularly in urban areas, due to the economic situation and the need to focus on meeting basic needs. As always, participation continues to be important and fundamental in many rural areas. There are important experiences and people wagering, dreaming and putting their heart and soul into this issue, many of whom I know and who are marvellous people. But we have to recognise our weaknesses. And one of those weaknesses is generating capacities and possibilities for participation. There is no doubt that, for this to improve, we need to improve people’s general social, working, and educational conditions. Otherwise it will be difficult to create spaces for protagonistic participation, as Chávez proposed and as laid out in the Laws of Popular Power.

Taking all this into consideration, can we say that the Maduro government today represents a break with the Bolivarian process?

Maduro himself has said it publicly and in clear terms: we are in a new stage. I am one of those who believes a slow shift has been occurring in economic and political terms for a few years now. If the issue of the elections is not resolved transparently, this shift could become a complete break [with the Bolivarian process]. This would put at risk Chavismo’s very identity and ability to rearm itself for what comes next.

This process of rearming will be a complex task given what I have said about the government tending to close itself off. Through its rhetoric, it tries to hide the reality that we are living. We have an official discourse that directly clashes with people’s daily reality. It is difficult to expand your support base when the government puts forward an official truth that can not be refuted or questioned. The government seeks to impose its version of reality on society. But when you are accustomed to using imposition and force to resolve differences and justify it by saying it is being used against the enemy, you soon end up using it against anyone. Today, branding anyone as manipulated by enemy propaganda, a traitor, a paid agent of imperialism or, worse, a fascist, has become a means to rule out any internal debate through simply negating the other. The government might be able to retain power this way, but the cost is tremendous. You cannot impose reality on a society, unless you attack society itself.

This is also made more complicated, at least for those of us who seek a revolutionary way out of the crisis, by the fact that we have business chamber representatives as PSUV parliamentarians, and the head of the Caracas Stock Exchange saying the opposition represents instability and suggesting it would be better to stick with what we have. When those are some of the spokespeople defending the continuity of Maduro’s government, it gives you some indication of the internal balance of forces and what the overriding political and economic tendency is within the government.

For these, and many other reasons, an important part of Chavismo no longer feels represented by this government. And many of those who continue to identify with the government have certain criticisms, but believe it is the best option for overcoming this difficult period in order to then retake the revolutionary path and go for more. I deeply respect their position, but I see that as highly unlikely. Nevertheless, I wish these comrades luck in their endeavours, which will undoubtedly be important for the challenges we face.

In any case, what we need today is a reconstruction of politics, and that requires recognising the other. We need to rethink politics in order to be able to convoke everyone, with our sights clearly set on the working-class majorities. That is how we can start rebuilding the country in terms of sovereignty and the social and labour rights that are being directly affected.

What implications does all this have for Chavista activists and for solidarity with the Bolivarian process?

The reality is that we live in a very difficult world. When you look at a map, you can see numerous conflicts across all continents — and everything indicates we are heading towards even greater confrontations. That weighs a lot on what is happening in Venezuela, because we are clearly and obviously caught in the middle of a geopolitical game, at the heart of which is control of our resources. That partly explains not just what has happened in more recent years, but everything that has happened in the country for the past century. But I believe that, as important as the current geopolitical game is, any calculation in terms of tipping the scales towards any of the factors in dispute should not be based on actions that directly go against our wellbeing and sovereignty.

I am very grateful for the solidarity we have received from comrades outside the country. I think you can support the government or criticise it, or even denounce it as representing a break with the process, but solidarity with the Venezuelan people must always remain firm. It must continue independently of one’s characterisation of the government or the opposition. What we have here is an accumulation of forces that has been minimised, deactivated and is in crisis, but no one can take away from us what we have built, and what we continue to build and dream about in many of our communities. That is why I ask that solidarity continue, just like with any other peoples in struggle facing difficulties, such as for example the people of Palestine or Argentina. We should be guided by a sense of class solidarity.

As for the government, if there has been a break, then this puts us in a very difficult situation when it comes to the kind of activism we have carried out during the Bolivarian Revolution. This is something we will have to resolve in some way. The same is true in terms of working with and maintaining communication with those working-class activists who continue to defend the government and for whom I have a lot of respect. Many of them are my brothers and sisters with whom we have fought thousands of battles in the street, in the community. It is up to us, even if it might seem difficult, to establish needed points of dialogues, not only as a means to get us out of the current dangerous political situation, but to reconfigure our strategy in terms of the Bolivarian Revolution.

We have already lived through extremely complicated moments in this country, and unfortunately, this will not be the last one. We will continue trying to do what we can, with what we can. And try to point to Chávez’s historic project, not out of nostalgia but to make use of the concrete forms of doing politics he left us. We must never forget that we have always been critically-minded working class activists. Even with Chávez, whom we always defended, we had to raise demands on more than one occasion, or march against specific policies. In that sense, we are not doing anything different to what we have always done — because it is our right and, moreover, our responsibility today.

No comments:

Post a Comment