Bloomberg News | October 4, 2024 |

Copper smelter. Stock Image.

Copper smelters are warning that plants may shut down or even go out of business if the industry’s processing fees drop too sharply, as annual supply negotiations with key miners get underway this week.

A wave of new smelter investments in China and elsewhere has left plants in growing competition to find enough ore to feed their furnaces, which means that miners can squeeze out increasingly attractive supply terms.

In private conversations, senior industry executives attending the annual LME Week said it’s likely that the key processing fee will fall to a level where smelters will struggle to turn a profit. The two sides began holding meetings this week to share their views on the market, although they have yet to put any numbers on the table, they said. There’s a broad expectation that the talks will be the toughest in years.

While the annual negotiations don’t get much attention outside of the metals world, this year the outcome could have far-reaching ramifications for the copper market. Smelter closures could reshape the map of global refined copper supply at a time of growing concerns about Chinese dominance over critical minerals. And, after a year in which the market for refined copper has been in oversupply even as miners struggled to lift output, the squeeze on smelters is likely to crimp refined supply — just as some expect China’s newly announced stimulus to kickstart consumption.

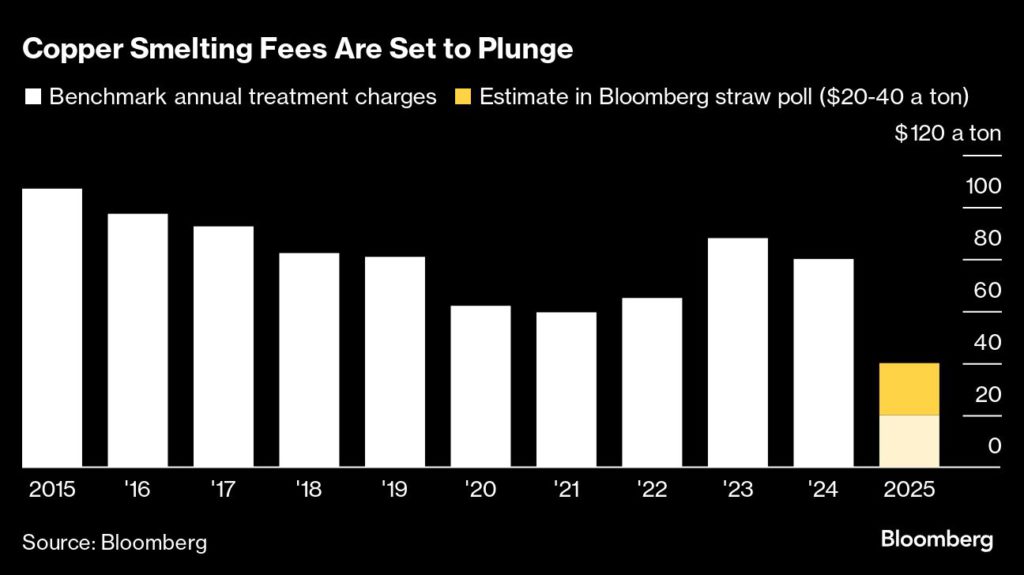

Smelters typically derive a large part of their profits from processing fees that are deducted from the cost of concentrates, the partly processed ore that they buy from miners. The industry agrees a benchmark for treatment and refining charges (TC/RCs) in the fourth quarter of each year — the fee is used as a reference for long-term supply contracts, while other ad hoc sales throughout the year are priced based on conditions at the time.

The mounting squeeze on ore supplies has led to a wide gulf between last year’s benchmark — which was set a $80 per ton of ore and 8 cents per pound of contained metal — and the terms being agreed in spot deals. The situation has grown so severe that the fees have turned negative; traders and smelters have been paying more for copper ore than the copper contained in it would fetch once processed, a highly unusual situation.

In a straw poll of more than two dozen miners, traders and smelters, respondents who provided an estimate said the benchmark would likely be agreed between $20 and $40 a ton and 2c to 4c a pound. Several respondents suggested that the negotiations could lead to a breakdown of the benchmark system, a potential watershed moment for the industry.

This year, the benchmark is expected to be negotiated with Chilean miner Antofagasta Plc, which in the past has tended to strike a tougher negotiating line than American rival Freeport-McMoRan Inc. The US company has often set the benchmark in recent years, but it will have far fewer concentrates to sell next year after building a huge new smelter next to its largest mine in Indonesia. Chief executive officer Kathleen Quirk said in an interview that Freeport won’t set the benchmark this year.

A spokesperson for Antofagasta declined to comment on the negotiations.

Representatives of Chinese smelters in London this week said they are emphasizing to Antofagasta that the industry already faces widening losses because there is not enough concentrate to go around, and warning that an aggressive cut to the benchmark fees could lead to production cuts and cause permanent damage to the industry. Officials at Chinese smelters said the industry would probably be lossmaking at fees below about $35 to $40 a ton.

“There’s been so much new capacity developed for smelters in China over the years, and there’s just not the concentrate available to feed everything,” Freeport’s Quirk said in London this week. “But for concentrate producers that are relying on smelters, they have to think: ‘Well, I don’t wanna push these guys out of business.’”

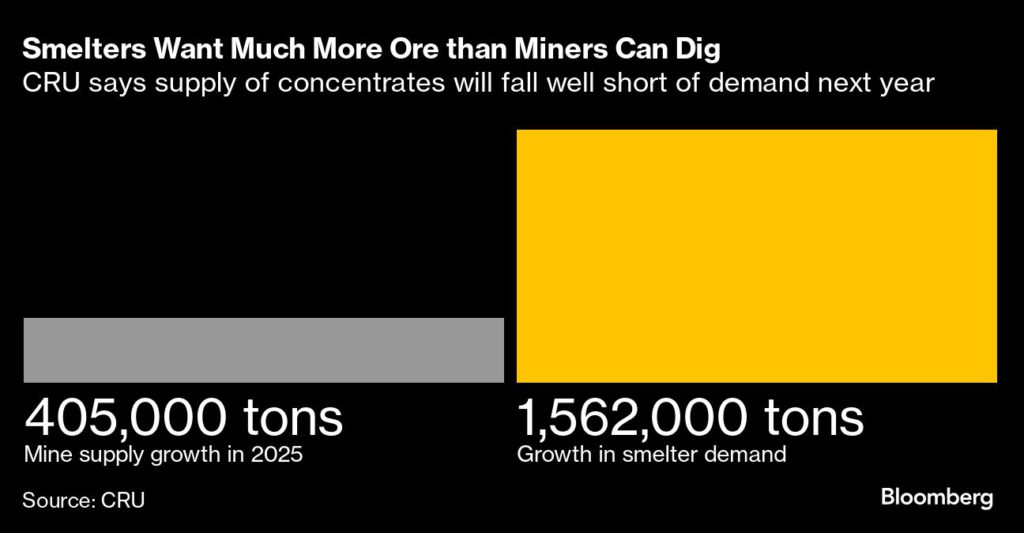

The huge mismatch between concentrate supply and demand stems from the commissioning of new plants in India, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as several major plant expansions in China. It’s also been a weak year for mine supply, but the rapid expansion in smelting capacity has fueled expectations that smelting margins will remain severely constrained even as mined output rebounds.

“We’ll maintain our production as we do have long-term supply contracts, and we’ll have to live with these lower TC/RCs for the coming year,” said Toralf Haag, who last month took over as CEO of Aurubis AG, Europe’s largest copper smelting group. “We’re optimistic that the situation will start to resolve itself over the coming year — some refining capacity will come off-stream, and some additional mining capacity will come onstream.”

Researcher CRU estimates that the difference between smelters’ needs and concentrate supply will balloon to about 1.2 million tons, the biggest deficit in at least a decade.

It expects that 70% of the gap will be resolved by smelters reducing their operating rates, but the remaining gap will need to be solved by temporary or permanent plant closures. And the more aggressive miners are in driving down TC/RCs, the more extensive the cuts will be, according to Erik Heimlich, the consultancy’s head of copper and zinc.

“Miners are in a very good position and they could force a very low TC/RC, but there are reasons that they won’t want to go as low as possible,” he said in an interview. “These are long-term relationships, and if you go very low, you’ll end up with an industry that loses a lot of players on the demand side.”

China’s fast-growing copper champion is reshaping global metal supply

Bloomberg News | October 2, 2024

Pictured: Zijinshan gold-copper mine.

Back at Zijinshan, in the earliest days, Chen’s team sought to find anything more lucrative than the scraps of gold that had been spotted in the area as far back as the Song dynasty, a thousand years earlier.

He led his team into the forest, and toward what turned out to be a major gold lode below the mountain’s peak. Under that, they found copper. Extraction didn’t start until the 1990s, but it turned Zijin into a poster child for Chinese mining.

In Chen’s telling, the experience ultimately defined the company.

“Technology and innovation is our key competitive advantage,” Chen said, a floor-to-ceiling photograph of Zijinshan looming behind him. “We have our own research, design, construction capacity, so our projects can be completed very fast.”

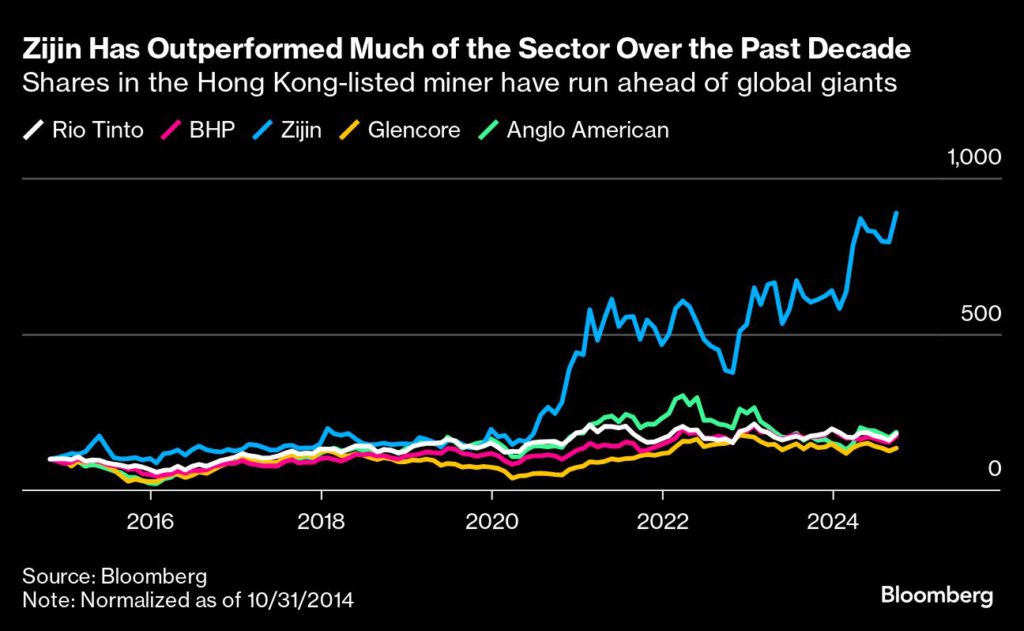

In reality, deals have mattered almost as much, accelerating after a 2003 Hong Kong listing. From 2006 until last year, Zijin spent at least $7 billion on acquisitions, most of them completed overseas and in the past decade. It invested in Glencore Plc’s convertible bond in 2009, a means of gaining information and, the group said at the time, access. It moved into battery metals in 2021, with Argentinian lithium.

“We always know that most of the world’s highest-quality and largest mineral resources are controlled by Western mining companies,” Chen said. “As a latecomer, the opportunities for acquisitions were always going to be relatively difficult.”

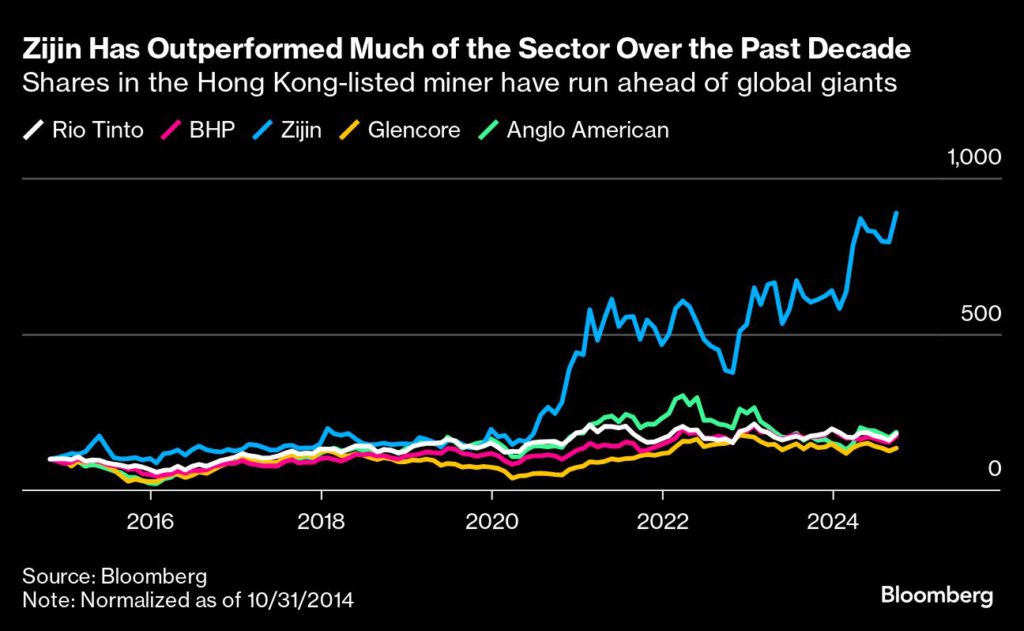

Many deals have been small — the biggest to date was Canada’s Nevsun Resources in 2018, snapped up for $1.4 billion in cash. But it’s the early-stage swoops that Zijin stands out for. It’s been enough to ensure the company is worth close to nine times more than it was a decade ago and can credibly target the position of top three copper miner. Output from Zijin’s mines is expected to climb to as much as 1.6 million tons of copper by 2028, up from 1 million last year — hefty, even if that includes some production attributable to other shareholders.

One such risk was a 2015 gamble on Canadian maverick Robert Friedland and his Kamoa project. Then, most of the industry was in debt and this was at best a promising project, tucked away in a remote corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now it’s one of the world’s biggest. Zijin bought into the mine and took a near-10% stake in Friedland’s Ivanhoe Mines Ltd, later increased. Today, Zijin and Ivanhoe both have a share in the operation of just under 40%.

“He’s been the high bidder for the best assets,” Friedland told Bloomberg. “And that is exactly Warren Buffett’s motto. Warren Buffett said, when I look back at my career, I always made the most money overpaying for the best assets.”

The mine produced almost 394,000 metric tons of copper concentrate in 2023 and Chen said Zijin was considering a pathway toward 1 million tons of annual output — ambitious, given the continued logistics and power supply challenges at Kamoa-Kakula.

“Our biggest regret in terms of M&A is that we didn’t manage to buy all of Ivanhoe at that time,” Chen said. “Robert was not willing.”

Zijin’s copper surge is well timed. The prospect of surging demand, as the energy transition takes hold, has already pushed the red metal to a record earlier this year. Large-scale new mines like Kamoa are rare.

“They are unburdened by the self-imposed constraints that Western mining companies — which are very risk adverse — face,” Friedland said. “It’s difficult to conceive of a future where Zijin doesn’t continue to have world leading growth.”

Read More: Zijin vows to keep investing in Canadian mining despite crackdown

Bloomberg News | October 2, 2024

Pictured: Zijinshan gold-copper mine.

(Image courtesy of Zijin Mining)

Chen Jinghe was not long out of university when a government official handed him the assignment that would change his life. Go to Zijin mountain, he was told, and find gold.

It was 1982, and the geology graduate found himself on forested slopes in the remote, humid highlands of southeastern China. The bet paid off. The deposit his team eventually discovered became the nation’s biggest gold mine — and the foundation for a $67 billion state-owned behemoth that is today driving copper supply growth and gaining ground on some of the most established names in the global resources industry.

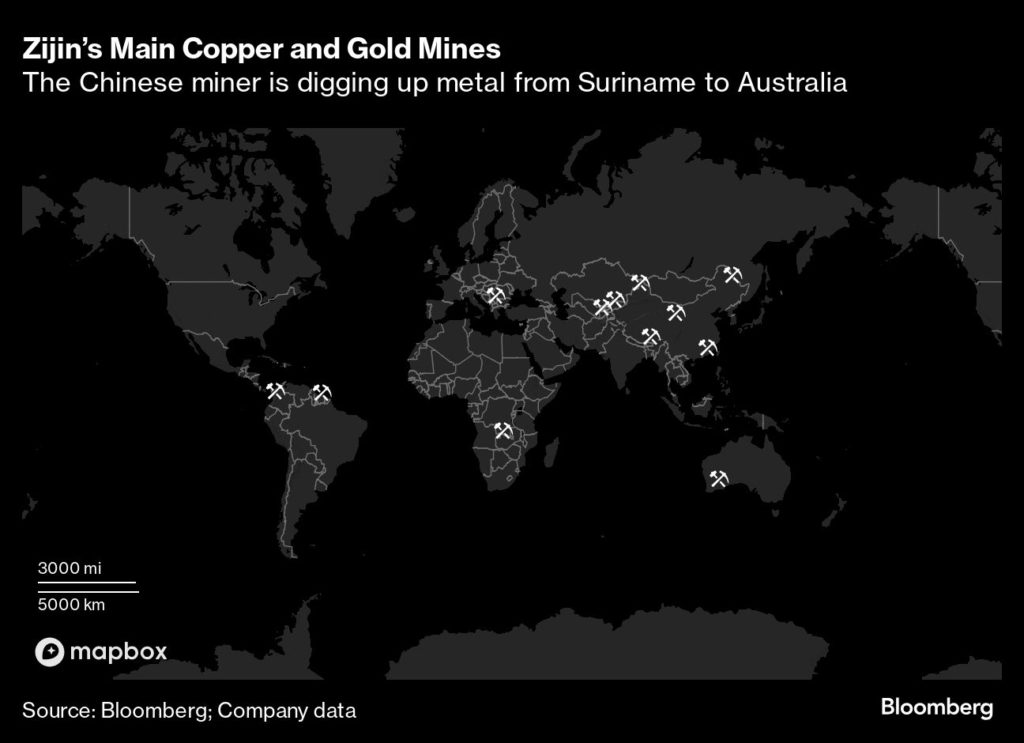

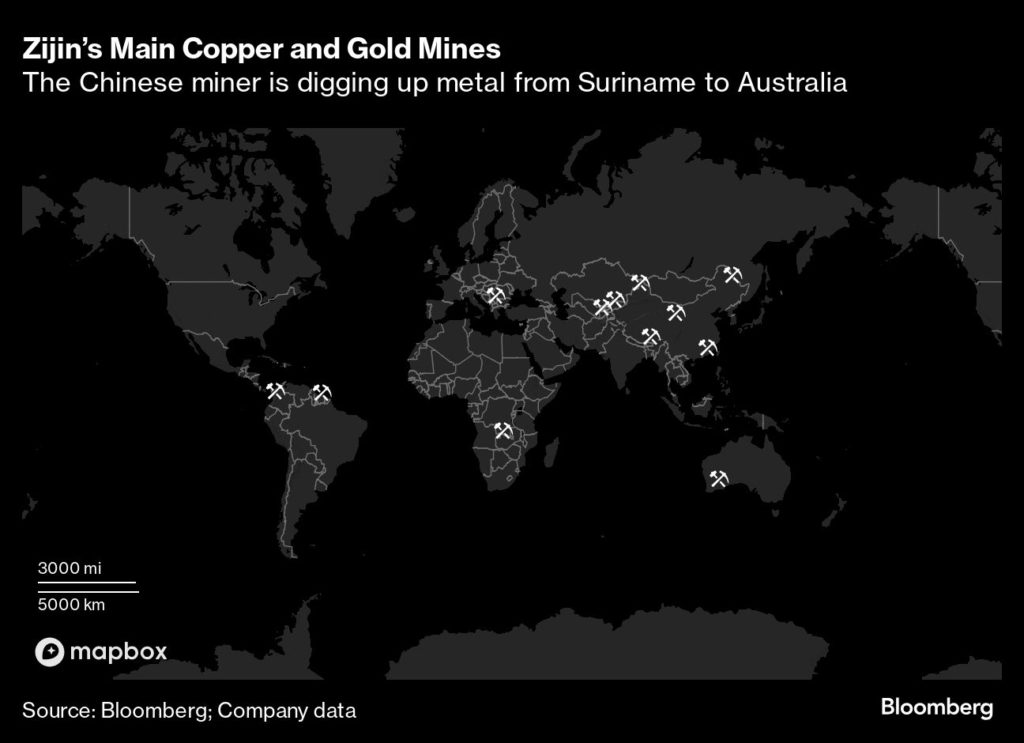

After a three-decade exploration and acquisition blitz, Zijin Mining Group Co. digs up gold, copper and lithium across multiple continents. A state-run company on paper, it has more frequently behaved like a private firm, with relatively few employees and a flexible, risk-tolerant approach to investments that has put it on track to join BHP Group Ltd. this decade among the very top ranks of copper producers.

“In the first ten years, we developed gold and copper at Zijinshan. In the second, we expanded across China. And in the past ten years, we’ve turned to global expansion,” the 66-year-old Chen said at the group’s headquarters in Xiamen, a coastal city some three hours’ drive east of the mine that gave the company its name.

Established Western names like Anglo American Plc limited spending over the past decade after the splurges of the last commodities boom, and most have yet to fully loosen the purse strings — but Zijin and peers like CMOC Group Ltd. have pressed ahead through the sector’s wilderness years. The result is that China, long dominant in refining and smelting, has now been able to dramatically expand its access to mined copper.

Zijin’s production of the metal has more than tripled over the past five years as new operations ramp up in Africa, the Balkans and at home. On an equity basis, it was the sixth-largest copper miner last year.

To a certain extent, the expansion tracks the nation’s broader rise to global growth engine and top commodity consumer. But Zijin is emblematic of a coterie of Chinese companies — both private and state-owned — changing the global metals landscape by generating a wave of mine supply, outpacing others with innovation and billions of dollars of investment, often in less-than-prime locations. China already dominated lithium refining, but has built up a robust lithium supply chain. Nickel too stands transformed.

Chen has previously described Zijin’s position as firmly in “the middle transition zone” between state firms and private rivals.

“They’re the fastest-growing copper miner and they fly a bit under the radar. They’ve ramped up mines internationally very successfully,” said Colin Hamilton, managing director for commodities research at BMO Capital Markets.

“People ask me if China could do in copper what they have done in lithium. The answer is, it’s a lot harder in copper, but a lot of the copper growth in the next few years is coming from places with significant Chinese investments.”

Granted, the blueprint is not as easy to follow as it was, between worsening geopolitical headwinds and a global scramble for critical minerals.

“As a Chinese company, future expansion will be more difficult,” Chen said, sitting back in an armchair in the company’s town-center office. “As investors, we cannot ignore these pressures.”

Resistance to Chinese acquisitions is growing across Western markets, and Canada’s curbs on foreign investment in mining have had particular significance for Zijin. The company has done more than $4 billion worth of deals with Toronto-listed companies since 2015. Even so, its plans to buy 15% of Toronto-listed copper miner Solaris Resources Inc. were scuttled in May, after a lengthy review by the federal government.

Solaris has since said it will relocate its head office to Quito. Zijin says it won’t give up on Canadian targets.

“All of this is quite regrettable,” Chen said, adding miners would feel the absence of Chinese capital. Firms like Zijin, which can take a longer, strategic view on raw material investments, have long been an important funding source for the junior mining sector.

But opportunities for Zijin will still come, he said, even if they emerge from locations where large, blue-chip Western miners still fear to tread.

“In order to have better options, we go to places with the richest resources in the world, even in places with relatively low development levels, or to places that many international mining companies consider problematic,” Chen said. “This is our differentiation.”

Not everything has gone Chen’s way over the past decades. In 2010, the company suffered a serious setback when acid leaked from its copper smelter at Zijinshan into the local river, killing enough fish to feed 72,000 people for a year and causing widespread panic. The toxic leak led to some Zijin and local government officials being charged, and Chen was handed a fine.

It was, Chen says, a mistake made by a young company. The company put up a memorial after the disaster, and marks the occasion annually. Today, he says, standards in some respects exceed those of Western counterparts.

More recently, Zijin has been swept up in US accusations of forced labor use in China’s western Xinjiang region. Its copper-gold unit there was sanctioned by the US in August, a development Chen said he met with “total shock and disbelief”. He said salaries were nearly double the local average, and added the company’s recruitment criteria required employees to be capable and to join of their own accord.

Chen Jinghe was not long out of university when a government official handed him the assignment that would change his life. Go to Zijin mountain, he was told, and find gold.

It was 1982, and the geology graduate found himself on forested slopes in the remote, humid highlands of southeastern China. The bet paid off. The deposit his team eventually discovered became the nation’s biggest gold mine — and the foundation for a $67 billion state-owned behemoth that is today driving copper supply growth and gaining ground on some of the most established names in the global resources industry.

After a three-decade exploration and acquisition blitz, Zijin Mining Group Co. digs up gold, copper and lithium across multiple continents. A state-run company on paper, it has more frequently behaved like a private firm, with relatively few employees and a flexible, risk-tolerant approach to investments that has put it on track to join BHP Group Ltd. this decade among the very top ranks of copper producers.

“In the first ten years, we developed gold and copper at Zijinshan. In the second, we expanded across China. And in the past ten years, we’ve turned to global expansion,” the 66-year-old Chen said at the group’s headquarters in Xiamen, a coastal city some three hours’ drive east of the mine that gave the company its name.

Established Western names like Anglo American Plc limited spending over the past decade after the splurges of the last commodities boom, and most have yet to fully loosen the purse strings — but Zijin and peers like CMOC Group Ltd. have pressed ahead through the sector’s wilderness years. The result is that China, long dominant in refining and smelting, has now been able to dramatically expand its access to mined copper.

Zijin’s production of the metal has more than tripled over the past five years as new operations ramp up in Africa, the Balkans and at home. On an equity basis, it was the sixth-largest copper miner last year.

To a certain extent, the expansion tracks the nation’s broader rise to global growth engine and top commodity consumer. But Zijin is emblematic of a coterie of Chinese companies — both private and state-owned — changing the global metals landscape by generating a wave of mine supply, outpacing others with innovation and billions of dollars of investment, often in less-than-prime locations. China already dominated lithium refining, but has built up a robust lithium supply chain. Nickel too stands transformed.

Chen has previously described Zijin’s position as firmly in “the middle transition zone” between state firms and private rivals.

“They’re the fastest-growing copper miner and they fly a bit under the radar. They’ve ramped up mines internationally very successfully,” said Colin Hamilton, managing director for commodities research at BMO Capital Markets.

“People ask me if China could do in copper what they have done in lithium. The answer is, it’s a lot harder in copper, but a lot of the copper growth in the next few years is coming from places with significant Chinese investments.”

Granted, the blueprint is not as easy to follow as it was, between worsening geopolitical headwinds and a global scramble for critical minerals.

“As a Chinese company, future expansion will be more difficult,” Chen said, sitting back in an armchair in the company’s town-center office. “As investors, we cannot ignore these pressures.”

Resistance to Chinese acquisitions is growing across Western markets, and Canada’s curbs on foreign investment in mining have had particular significance for Zijin. The company has done more than $4 billion worth of deals with Toronto-listed companies since 2015. Even so, its plans to buy 15% of Toronto-listed copper miner Solaris Resources Inc. were scuttled in May, after a lengthy review by the federal government.

Solaris has since said it will relocate its head office to Quito. Zijin says it won’t give up on Canadian targets.

“All of this is quite regrettable,” Chen said, adding miners would feel the absence of Chinese capital. Firms like Zijin, which can take a longer, strategic view on raw material investments, have long been an important funding source for the junior mining sector.

But opportunities for Zijin will still come, he said, even if they emerge from locations where large, blue-chip Western miners still fear to tread.

“In order to have better options, we go to places with the richest resources in the world, even in places with relatively low development levels, or to places that many international mining companies consider problematic,” Chen said. “This is our differentiation.”

Not everything has gone Chen’s way over the past decades. In 2010, the company suffered a serious setback when acid leaked from its copper smelter at Zijinshan into the local river, killing enough fish to feed 72,000 people for a year and causing widespread panic. The toxic leak led to some Zijin and local government officials being charged, and Chen was handed a fine.

It was, Chen says, a mistake made by a young company. The company put up a memorial after the disaster, and marks the occasion annually. Today, he says, standards in some respects exceed those of Western counterparts.

More recently, Zijin has been swept up in US accusations of forced labor use in China’s western Xinjiang region. Its copper-gold unit there was sanctioned by the US in August, a development Chen said he met with “total shock and disbelief”. He said salaries were nearly double the local average, and added the company’s recruitment criteria required employees to be capable and to join of their own accord.

Back at Zijinshan, in the earliest days, Chen’s team sought to find anything more lucrative than the scraps of gold that had been spotted in the area as far back as the Song dynasty, a thousand years earlier.

He led his team into the forest, and toward what turned out to be a major gold lode below the mountain’s peak. Under that, they found copper. Extraction didn’t start until the 1990s, but it turned Zijin into a poster child for Chinese mining.

In Chen’s telling, the experience ultimately defined the company.

“Technology and innovation is our key competitive advantage,” Chen said, a floor-to-ceiling photograph of Zijinshan looming behind him. “We have our own research, design, construction capacity, so our projects can be completed very fast.”

In reality, deals have mattered almost as much, accelerating after a 2003 Hong Kong listing. From 2006 until last year, Zijin spent at least $7 billion on acquisitions, most of them completed overseas and in the past decade. It invested in Glencore Plc’s convertible bond in 2009, a means of gaining information and, the group said at the time, access. It moved into battery metals in 2021, with Argentinian lithium.

“We always know that most of the world’s highest-quality and largest mineral resources are controlled by Western mining companies,” Chen said. “As a latecomer, the opportunities for acquisitions were always going to be relatively difficult.”

Many deals have been small — the biggest to date was Canada’s Nevsun Resources in 2018, snapped up for $1.4 billion in cash. But it’s the early-stage swoops that Zijin stands out for. It’s been enough to ensure the company is worth close to nine times more than it was a decade ago and can credibly target the position of top three copper miner. Output from Zijin’s mines is expected to climb to as much as 1.6 million tons of copper by 2028, up from 1 million last year — hefty, even if that includes some production attributable to other shareholders.

One such risk was a 2015 gamble on Canadian maverick Robert Friedland and his Kamoa project. Then, most of the industry was in debt and this was at best a promising project, tucked away in a remote corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now it’s one of the world’s biggest. Zijin bought into the mine and took a near-10% stake in Friedland’s Ivanhoe Mines Ltd, later increased. Today, Zijin and Ivanhoe both have a share in the operation of just under 40%.

“He’s been the high bidder for the best assets,” Friedland told Bloomberg. “And that is exactly Warren Buffett’s motto. Warren Buffett said, when I look back at my career, I always made the most money overpaying for the best assets.”

The mine produced almost 394,000 metric tons of copper concentrate in 2023 and Chen said Zijin was considering a pathway toward 1 million tons of annual output — ambitious, given the continued logistics and power supply challenges at Kamoa-Kakula.

“Our biggest regret in terms of M&A is that we didn’t manage to buy all of Ivanhoe at that time,” Chen said. “Robert was not willing.”

Zijin’s copper surge is well timed. The prospect of surging demand, as the energy transition takes hold, has already pushed the red metal to a record earlier this year. Large-scale new mines like Kamoa are rare.

“They are unburdened by the self-imposed constraints that Western mining companies — which are very risk adverse — face,” Friedland said. “It’s difficult to conceive of a future where Zijin doesn’t continue to have world leading growth.”

Read More: Zijin vows to keep investing in Canadian mining despite crackdown

No comments:

Post a Comment