GAO: Maintenance Issues Have Cut U.S. Army Fleet's Readiness in Half

The U.S. military's heavy landing craft fleet does not live under the Navy or the Marine Corps, but under the U.S. Army's Watercraft Systems division - and it is in trouble, according to the Government Accountability Office.

The Army operates a little-known fleet of bow-ramp landing ships and watercraft, from mini-tugs up to the 275-foot Besson-class logistics support ships. With enough deadweight for up to two dozen Abrams battle tanks, and enough range to cross the Pacific, the Besson-class ships are by far the biggest active U.S. military vessels that can land troops directly onto a beach.

The Army began downsizing its watercraft fleet in 2018, when it had more than 130 vessels. The initiative proceeded in fits and starts, but by 2023, the service had reduced the division's size to 70 active vessels. This fleet count includes the Modular Causeway System, the heart of the Joint Logistics Over the Shore (JLOTS) temporary pier capability, which encountered severe operational difficulties off Gaza this year.

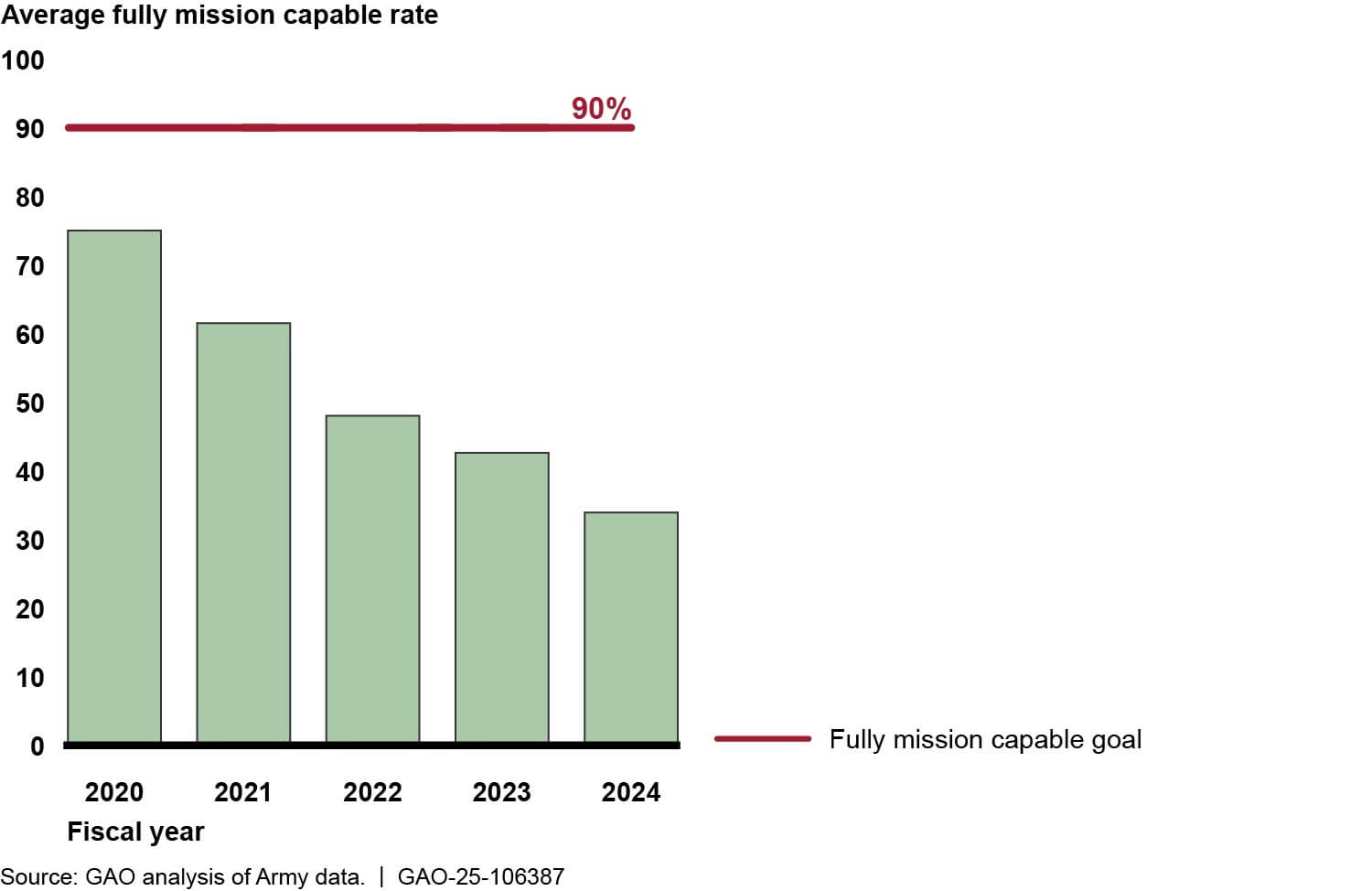

According to GAO, the capability of the Army's remaining watercraft force is eroding because of persistent maintenance challenges. The Army watercraft fleet's average fully mission capable availability rate should ideally be 90 percent, and in 2020 it sat at 75 percent. It has dropped every year since, and over the course of 2024, the average availability rate was 35 percent.

Low availability reduces the fleet's ability to meet mission requirements, even as demand for Army landing craft increases in Indo-Pacific Command. Two-thirds of the Army fleet will be transferred to the Indo-Pacific by 2030, reflecting the new focus on geostrategic competition in this region.

Part of the problem is the advancing age of the fleet. The most in-demand vessels, the LSV and LCU landing ships, are mostly in their 30s and are showing signs of age. Supply shortages, unexpected repairs and obsolete parts for these 1990s-era vessels are making normal shipyard periods run longer - in some cases, years longer.

GAO found that the Army's newest and largest landing ship, USAV Major General Robert Smalls (LSV-8), was "left unattended" in Baltimore for two years from 2018-2020. The layup period occurred after the Army's decision to deactivate all its Army Reserve watercraft units, and the neglected ship required 2,100 days of shipyard time because of "cumulative effect of unaddressed issues and complex repair contracts," exacerbated by the "absence of a regular crew." The Smalls only returned to service at Fort Eustis, Virginia in May 2024.

Likewise, USAV El Caney (LCU-2017) entered a yard period for a service life extension in 2018 and was still under repair in mid-2024, more than five years later. Unexpected hull damage and repeated problems in finding parts dragged out the project and forced seven contract modifications.

GAO also found that the Watercraft Inspection Branch - one of three offices responsible for vessel maintenance - still uses handwritten work orders to track events, not the enterprise data systems that are used by the rest of the service. The paper-based management system means that the office can't readily analyze trends across the fleet - for example, the parts availability issues for the service's aging vessels.

GAO recommended that the Army should improve the governance of its watercraft program, start tracking maintenance electronically, and work with Indo-Pacific Command to bridge any gaps in landing craft capability in the region where it is needed most. The Army concurred with all recommendations.

No comments:

Post a Comment