Health risks are rising in mountain areas flooded by Hurricane Helene and cut off from clean water, power and hospitals

Jennifer Horney, University of Delaware

Tue, October 1, 2024

THE CONVERSATION

Flooding across North Carolina's mountains left many residents with muddy, debris-strewn yards and flooded homes Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

Hurricane Helene’s flooding has subsided, but health risks are growing in hard-hit regions of the North Carolina mountains, where many people lost access to power and clean water.

More than 150 deaths across the Southeast had been attributed to Hurricane Helene within days of the late September 2024 storm, according to The Associated Press, and hundreds of people remained unaccounted for. In many areas hit by flooding, homes were left isolated by damaged roads and bridges. Phone service was down. And electricity was likely to be out for weeks.

As a disaster epidemiologist and a native North Carolinian, I have been hearing stories from the region that are devastating. Contaminated water is one of the leading health risks, but residents also face harm to mental health, stress that exacerbates chronic diseases and several other threats.

Water risks: What you can’t see can hurt you

Access to clean water is one of the most urgent health concerns after a flood. People need water for drinking, preparing food, cleaning, bathing, even flushing toilets. Contact with contaminated water can cause serious illnesses.

Floodwater with sewage or other harmful contaminants in it can lead to infectious diseases, particularly among people who are already ill, immunocompromised or have open wounds. Even after the water recedes, residents may underestimate the potential for contamination by unseen bacteria such as fecal coliform, heavy metals such as lead, and organic and inorganic contaminants such as pesticides.

People wait in long lines in Fletcher, N.C., on Sept. 29, 2024, for gasoline to run generators after Hurricane Helene cut power across the mountain region. Sean Rayford/Getty Images

In Asheville, the flooding caused so much damage to water treatment facilities and pipes that officials warned the city could be without running water for potentially weeks. Most private wells also require electricity to pump and filter the water, and many people in surrounding areas could be without power for weeks.

State and federal agencies began delivering extra bottled water to the region shortly after the storm, but supplies were limited, and it’s likely that a number of people won’t be able to reach the distribution sites soon. Access to fresh food is another concern for many areas with roads and bridges washed out.

Inside homes, floodwater can create more health risks, particularly if mold grows on wet fabrics and wallboard. Standing water outside also increases the risk of exposure to mosquitoes carrying diseases such as West Nile virus. Mosquitoes are still active in much of the region in the fall.

Inundation, isolation and access to health care

Many of the images in the news after the hurricane hit showed roads, hospitals and entire towns inundated by floodwaters. In North Carolina, more than 400 roads were closed, blocking access to the major regional health care hub of Asheville, as well as many smaller communities.

While supplies can be airlifted to clinics, residents needing urgent access to treatments such as dialysis or daily medications for substance use disorders may have been cut off. Health care workers may be unable to access their clinics as well.

Flooding in homes can create conditions for mold to grow, even after the mud and water have been cleaned up. Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

Cuts and other injuries are common in the aftermath of storms, as people clean up debris, and even small wounds can become infected. The stress, exertion and exposure to heat can also exacerbate chronic conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

Mental health and long-term effects

Beyond the risks to physical health, the fear, stress and losses can affect mental health.

Research has consistently shown that emergency responders’ mental health can suffer in widespread disasters, particularly when they know disaster victims, deal with severe injuries or feel helpless. All of those conditions were present as Hurricane Helene’s floodwaters swept away dozens of people, with many more still listed as missing.

Fast-moving floodwaters from Helene washed out roads and bridges across western North Carolina, including this bridge on Highway 22 near North Cove. Photo by Julia Wall for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Stigma, cost and a lack of mental health care providers all add to the ongoing challenges to mental health after disasters. Research shows that a large percentage of people face mental health challenges after disasters.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, two federal grant programs provide mental health services support to individuals and communities after disasters. However, one of those sources of funding ends after 60 days, the other after one year. Given the decades of recovery facing western North Carolina after Hurricane Helene, I believe these programs are woefully inadequate to meet the mental health needs of the populations affected by the storm.

Flooded regions will need long-term help

Western North Carolina is often described as a “climate refuge” because of its cooler summers. And Asheville in particular has become a popular place for retirees and new residents. Recent data shows the city has the second highest migration rate in the nation.

But Helene and other extreme storms that have flooded the region make its vulnerabilities clear.

In the aftermath of the flooding, newcomers unfamiliar with the risks and longtime residents alike will be dealing with ongoing health concerns as they try to clean up and rebuild from the storm. Even as attention shifts to other disasters, the people in this region will still need help to recover for months and years to come.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jennifer Horney, University of Delaware

Read more:

In storms like Hurricane Helene, flooded industrial sites and toxic chemical releases are a silent and growing threat

Hurricane Helene power outages leave millions in the dark – history shows poorer areas often wait longest for electricity to be restored

Hurricanes don’t stop at the coast – these mountain towns know how severe inland flood damage can be, and they’re watching Helene

Jennifer Horney receives funding from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), National Science Foundation (NSF), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA), Delaware SeaGrant, Delaware Department of Transportation and Delaware Division of Public Health

Gavin Off

Wed, October 2, 2024

Few people in Mecklenburg County suffered more from Hurricane Helene than residents whose homes border the Catwaba River south of Mountain Island Lake.

Floodwater there covered streets. It gushed into homes and filled backyard out buildings with near ceiling-level brown water. A preliminary assessment found four homes to be total losses, said Paige Grande, a spokesperson for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Emergency Management. People living in about 100 houses were displaced.

Lake Drive resident Erik Jendresen, who’s sued the Duke Energy before over flooding, says the power company shares the blame.

Jendresen lives just downstream of Mountain Island Lake, where water levels were above Duke Energy’s target in the days leading up to Helene’s arrival, according to the company’s website.

Water levels at Lake Norman, just north, were near target levels but above minimums, data show.

Jendresen questioned why the power company didn’t release some water — at Mountain Island Lake and others — in anticipation of the influx of water streaming down from the mountains. Lowering the water levels ahead of time and increasing the lake’s storage capacity would have prevented the lake from sending so much water over the spillway at once, Jendresen said.

A smaller spill means a smaller impact on communities downstream.

“They could have taken steps well in advance to drastically lower levels at all lakes in the 11-lake system to the bare minimum they’re allowed to,” said Jendresen, 64. “There’s a perception that Duke is like the evil empire. They’ve earned it.”

Duke Energy did not respond to the Observer’s questions Tuesday or Wednesday.

The company began moving water through the entire system on Sept. 25, Ben Williamson, a Duke Energy spokesperson, told WCNC, which first reported on Duke not significantly lowering water levels before Helene.

Williamson said rainfall totals for Helene exceeded expectations, and all of that water had to flow downstream.

”Due to the size of Mountain Island Lake, one of the smallest lakes on the Catawba-Wateree River, and the historic amount of rainfall from this event, any additional storage that would have been created in Mountain Island would not have prevented the flooding experienced on Mountain Island Lake, or in the upper reaches of Lake Wylie below Mountain Island Lake during this historic event,” Williamson told WCNC.

Flood of record

Brandon Jones has been the Catawba Riverkeeper since 2018. He’s never seen the river flood like it did last week. It’s likely no one else has, either.

“This will be the flood of record,” Jones said. “We talk about the great flood of 1916. This is bigger. This has more damage. This is more catastrophic.”

Helene dumped nearly two feet of rain on some parts of western North Carolina. Eighteen inches fell onto part of McDowell County, which sits in the Catawba River basin, according to North Carolina State University.

The river, which changes to the Wateree River in South Carolina, starts in the Blue Ridge Mountains and runs 225 miles through 26 counties across the Carolinas.

Jones said one of the river’s bottlenecks is the Mountain Island Lake dam. Unlike other dams along the Catawba, the one south of Mountain Island Lake doesn’t have flood gates. Water can only move through the dam’s spillway or hydroelectric turbines, Jones said.

“The important thing to remember is Duke is not able to quickly move water through the system,” he said. “They need a long run up time because the reservoirs were not designed for flood control. So when the forecast changes quickly or worsens, they are unable to adjust.”

Jones said Mountain Island Lake’s turbines can move about 10,000 cubic feet of water per second — or about 75,000 gallons per second. He said the influx of water into the lake peaked at about 100,000 cubic feet per second.

“I would expect this to be a 1,000-year flood,” he said. “It’s terrible. And all of these people just recovered from the last flood in 2019.”

Catawba River flooded homes in 2019

In June 2019, after three days of rain, Duke released what was then the largest amount of water ever from Lake Norman. Water poured into more than 100 homes, including many on Lake and Riverside drives near Mountain Island Lake.

The rush of water filled Jendresen’s home with about five feet of the swollen, muddy river.

He and roughly 40 other families sued Duke Energy. They accused the power company of negligence and negligent infliction of emotional distress and settled the lawsuit last year.

Jendresen rebuilt after the 2019 flood, but he did so on 12-foot pilings. He told the Observer on Tuesday that his home was eight inches away from flooding again. He said his house was one of only a few on Lake or Riverside drives that wasn’t harmed by the recent surge.

Many weren’t so lucky.

“Nobody got hurt,” he said. “But there’s a lot of hurt feelings and a lot of ruined lives.”

Grande, with Mecklenburg County Emergency Management, said an official assessment of the damage on Lake and Riverside drives will begin Wednesday. The assessment, she said, would take about a week.

In our Reality Check stories, Charlotte Observer journalists dig deeper into questions over facts, consequences and accountability. Read more. Story idea? RealityCheck@charlotteobserver.com.

‘Nowhere is safe’: shattered Asheville shows stunning reach of climate crisis

Oliver Milman

THE GUARDIAN

Tue, October 1, 2024

Flooding from Hurricane Helene in Asheville, North Carolina, on Saturday.Photograph: Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

Nestled in the bucolic Blue Ridge mountains of western North Carolina and far from any coast, Asheville was touted as a climate “haven” from extreme weather. Now the historic city has been devastated and cut off by Hurricane Helene’s catastrophic floodwaters, in a stunning display of the climate crisis’s unlimited reach in the United States.

Helene, which crunched into the western Florida coast as a category 4 hurricane on Thursday, brought darkly familiar carnage to a stretch of that state that has experienced three such storms in the past 13 months, flattening coastal homes and tossing boats inland.

But as the storm, with winds peaking at 140mph (225 km/h), carved a path northwards, it mangled places in multiple states that have never seen such impacts, obliterating small towns, hurling trees on to homes, unmooring houses that then floated in the floodwater, plunging millions of people into power blackouts and turning major roads into rivers.

Related: Over 120 dead and a million without power after ‘historic’ Hurricane Helene

In all, about 100 people have died across five states, with nearly a third of these deaths occurring in the county containing Asheville, a city of historic architecture where new residents have flocked amid boasts by real estate agents of a place that offers a reprieve from “crazy” extreme weather.

Now, major highways into Asheville have been severed by flooding from surging rainfall, its mud-caked and debris-strewn center turned into a place where access to cellphone reception, gasoline and food is scarce. The water supply, as well as the roads, is expected to be affected for weeks. It is, according to Roy Cooper, North Carolina’s governor, an “unprecedented tragedy”.

“Everyone thought this was a safe place, somewhere you could move with your kids for the long term, so this is just unimaginable, it’s catastrophic,” said Anna Jane Joyner, a climate campaigner who grew up in the area and whose family still lives in Black Mountain, near Asheville. Several of her friends narrowly avoided being swept away by the floodwater.

“I never, ever considered the idea that Asheville would be wiped out,” she said. “It was our backup plan to move there, so the irony is stark and scary and it’s hard for me to emotionally process. I’ve been working in the climate movement for 20 years and feel like I’m now living in a movie I imagined in my head when I started. Nowhere is safe now.”

The damage wrought by Helene is “a staggering and horrific reminder of the ways that the climate crisis can turbocharge extreme weather”, according to Al Gore, the former US vice-president. Hurricanes gain strength from heat in the ocean and atmosphere and Helene, one of the largest ever documented, sped across a record-hot Gulf, quickly turning from a category 1 to a category 4 storm within a day.

Extra heat not only helps storms spin faster, it also holds more atmospheric moisture that is then unleashed in torrents upon places such as western North Carolina, which got a month’s rain in just a couple of days. Helene was the eighth category 4 or 5 hurricane to strike the US since 2017 – the same number of such extreme storms to hit the country in the previous 57 years.

“This storm has the fingerprints of climate change all over it,” said Kathie Dello, North Carolina’s state climatologist. “The ocean was warm and it grew and grew and there was a lot of water in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, our worst fears came true. Helene was supercharged by climate change and we should expect more storms like this going forward.”

Dello said that it would take months or even years for communities, particularly in the poorer, more rural areas of the state that have been cut off completely by the storm, to recover, compounding the impacts of previous storms such as Florence, in 2018, and Fred, in 2021, that pose major questions over how, if at all, to rebuild.

“I don’t know where you run to escape climate change. Everywhere has some sort of risk,” she said. “It’s really been quite rattling to see these places which you love be devastated, knowing they have been changed forever. We can’t just rebuild like before.”

In Asheville, the historic area of Biltmore Village has been submerged underwater while, in a gloomy irony, the US’s premier climate data center has been knocked offline.

The storm has been “devastating for our folks in Asheville”, said a spokesperson for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who said the National Centers for Environmental Information facility had lost its water supply and had shut down.

“Even those who are physically safe are generally without power, water or connectivity,” the spokesperson said of the effort to contact the center’s marooned staff.

The destruction may cast a shadow over the climate-haven reputation of Asheville, much like how Vermont’s apparent distance from the climate crisis has been rethought in the wake of recent floods, but it probably won’t defy a broader trend where Americans are flocking to some of the places most at risk from heatwaves, storms and other climate impacts due to the ready availability of housing and jobs.

“This flood will likely accelerate development,” said Jesse Keenan, an expert in climate adaptation at Tulane University, who noted that for every one person who moves away from Asheville, three people move to the city, one of the highest such ratios in the US.

“Some people will not be inclined or unable to rebuild and their properties will be bought up by wealthy people who can afford to build private infrastructure and buildings that have the engineering resilience to withstand floods.”

“There is no truly safe place,” Keenan, who previously listed Asheville as one of the better places to move amid the climate crisis, acknowledged. But the city will “see a post-disaster boom”, he said. “This is a cycle that has happened over and over again in America.”

Destructive hurricanes like Helene highlight that catastrophic impacts from storms can extend far inland

Tue, October 1, 2024

Flooding from Hurricane Helene in Asheville, North Carolina, on Saturday.Photograph: Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

Nestled in the bucolic Blue Ridge mountains of western North Carolina and far from any coast, Asheville was touted as a climate “haven” from extreme weather. Now the historic city has been devastated and cut off by Hurricane Helene’s catastrophic floodwaters, in a stunning display of the climate crisis’s unlimited reach in the United States.

Helene, which crunched into the western Florida coast as a category 4 hurricane on Thursday, brought darkly familiar carnage to a stretch of that state that has experienced three such storms in the past 13 months, flattening coastal homes and tossing boats inland.

But as the storm, with winds peaking at 140mph (225 km/h), carved a path northwards, it mangled places in multiple states that have never seen such impacts, obliterating small towns, hurling trees on to homes, unmooring houses that then floated in the floodwater, plunging millions of people into power blackouts and turning major roads into rivers.

Related: Over 120 dead and a million without power after ‘historic’ Hurricane Helene

In all, about 100 people have died across five states, with nearly a third of these deaths occurring in the county containing Asheville, a city of historic architecture where new residents have flocked amid boasts by real estate agents of a place that offers a reprieve from “crazy” extreme weather.

Now, major highways into Asheville have been severed by flooding from surging rainfall, its mud-caked and debris-strewn center turned into a place where access to cellphone reception, gasoline and food is scarce. The water supply, as well as the roads, is expected to be affected for weeks. It is, according to Roy Cooper, North Carolina’s governor, an “unprecedented tragedy”.

“Everyone thought this was a safe place, somewhere you could move with your kids for the long term, so this is just unimaginable, it’s catastrophic,” said Anna Jane Joyner, a climate campaigner who grew up in the area and whose family still lives in Black Mountain, near Asheville. Several of her friends narrowly avoided being swept away by the floodwater.

“I never, ever considered the idea that Asheville would be wiped out,” she said. “It was our backup plan to move there, so the irony is stark and scary and it’s hard for me to emotionally process. I’ve been working in the climate movement for 20 years and feel like I’m now living in a movie I imagined in my head when I started. Nowhere is safe now.”

The damage wrought by Helene is “a staggering and horrific reminder of the ways that the climate crisis can turbocharge extreme weather”, according to Al Gore, the former US vice-president. Hurricanes gain strength from heat in the ocean and atmosphere and Helene, one of the largest ever documented, sped across a record-hot Gulf, quickly turning from a category 1 to a category 4 storm within a day.

Extra heat not only helps storms spin faster, it also holds more atmospheric moisture that is then unleashed in torrents upon places such as western North Carolina, which got a month’s rain in just a couple of days. Helene was the eighth category 4 or 5 hurricane to strike the US since 2017 – the same number of such extreme storms to hit the country in the previous 57 years.

“This storm has the fingerprints of climate change all over it,” said Kathie Dello, North Carolina’s state climatologist. “The ocean was warm and it grew and grew and there was a lot of water in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, our worst fears came true. Helene was supercharged by climate change and we should expect more storms like this going forward.”

Dello said that it would take months or even years for communities, particularly in the poorer, more rural areas of the state that have been cut off completely by the storm, to recover, compounding the impacts of previous storms such as Florence, in 2018, and Fred, in 2021, that pose major questions over how, if at all, to rebuild.

“I don’t know where you run to escape climate change. Everywhere has some sort of risk,” she said. “It’s really been quite rattling to see these places which you love be devastated, knowing they have been changed forever. We can’t just rebuild like before.”

In Asheville, the historic area of Biltmore Village has been submerged underwater while, in a gloomy irony, the US’s premier climate data center has been knocked offline.

The storm has been “devastating for our folks in Asheville”, said a spokesperson for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who said the National Centers for Environmental Information facility had lost its water supply and had shut down.

“Even those who are physically safe are generally without power, water or connectivity,” the spokesperson said of the effort to contact the center’s marooned staff.

The destruction may cast a shadow over the climate-haven reputation of Asheville, much like how Vermont’s apparent distance from the climate crisis has been rethought in the wake of recent floods, but it probably won’t defy a broader trend where Americans are flocking to some of the places most at risk from heatwaves, storms and other climate impacts due to the ready availability of housing and jobs.

“This flood will likely accelerate development,” said Jesse Keenan, an expert in climate adaptation at Tulane University, who noted that for every one person who moves away from Asheville, three people move to the city, one of the highest such ratios in the US.

“Some people will not be inclined or unable to rebuild and their properties will be bought up by wealthy people who can afford to build private infrastructure and buildings that have the engineering resilience to withstand floods.”

“There is no truly safe place,” Keenan, who previously listed Asheville as one of the better places to move amid the climate crisis, acknowledged. But the city will “see a post-disaster boom”, he said. “This is a cycle that has happened over and over again in America.”

Destructive hurricanes like Helene highlight that catastrophic impacts from storms can extend far inland

JULIA JACOBO

Wed, October 2, 2024

Destructive hurricanes like Helene are a stark reminder that significant and devastating impacts from many major storms are not relegated to coastal cities and communities -- inland regions often face catastrophic impacts too, experts are warning.

The Category 4 hurricane made landfall on Florida's Big Bend region Thursday night before tracking north, leaving a wake of destruction over 400 miles in the days the followed.

MORE: Hundreds of miles from landfall, Hurricane Helene's 'apocalyptic' devastation unfolds

The storm brought 140 mph winds and a 15-foot storm surge to parts of the Gulf Coast, along with more than 20 reported tornadoes in five states. Helene, combined with a separate system, dumped over 30 inches of rain in parts of North Carolina over the span of a few days. At least 177 people died as a result of the storm, with many still unaccounted for.

Inland communities need to be prepared when tropical storms or heavy rain events hit, Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told ABC News.

"We expect these sorts of events to happen more often," Francis said, adding that climate change is playing a major factor in these situations.

PHOTO: An unidentified man paddles a canoe to rescue residents and their belongings at a flooded apartment complex after Hurricane Helene passed the area on Friday, Sept. 27, 2024, in Atlanta. (Ron Harris/AP)

Because of the far-reaching impacts of tropical systems, meteorologists are now adding a growing number of regions to their forecasts, Marshall Shepherd, director of the Atmospheric Sciences Program at the University of Georgia and former president of the American Meteorological Society, told ABC News.

Human-amplified climate change is likely influencing the behavior of hurricanes in a variety of ways, research shows. Warmer sea temperatures are providing more fuel for tropical systems intensify more rapidly as they near the coast. More moisture in the atmosphere is trigger more frequent extreme rainfall events. Some systems are stalling after hitting land, resulting in prolonged periods of intense rainfall over specific areas.

MORE: After Helene, searches continue for scores of loved ones unaccounted for after devastating storm

Several hurricanes that have struck in the last decade serve as a grim reminder that devastating impacts frequently extend far inland from where a storm first makes landfall along the coast, experts say.

Hurricane Ida and its remnants impacted a wide swath of the continental U.S. after making landfall in Louisiana in 2021 as a Category 4 storm. By the time the system got to the Northeast days later, it had transitioned into an extra tropical system that dumped over 3 inches of rain in one hour in New York City's Central Park, causing deadly flash flooding in some parts of the city.

"So much rain fell over a short period of time that you just got this massive flooding," Shepherd said. "That was what was overwhelming New York City."

PHOTO: Debris is seen in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, Sept. 30, 2024, in Asheville, N.C. (Mike Stewart/AP)

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey slowed down after making landfall in eastern Texas as a Category 4 storm, bringing torrential rain and flooding to the Houston area for days even after it weakened to a tropical storm, Shepherd said.

Storm surge and rainfall are the deadliest impacts of hurricanes, which is why the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, which ranks the strength of tropical systems based on wind speeds, does not tell the whole story of the threats a hurricane presents, Shepherd said.

"There's a lot of work out there on alternative ways of representing the hazards from hurricanes," he said.

MORE: Climate change making Atlantic hurricanes twice as likely to strengthen from weak to major intensity in 24 hours

Multiple factors played into the catastrophic rainfall near Asheville, North Carolina, which had undergone a heavy rain event just before Helene, Shepherd said.

One of these factors is called orographic lifting. This occurs when air is forced to rise over a mountain and cool, causing water vapor to condense. This triggers cloud and precipitation that likely combined with Helene's tropical system to cause the torrential downpour, Shepherd said. The sheer size of the system extended the reach of the storm and researchers are looking into whether an atmospheric river also contributed to the heavy precipitation, Shepherd said.

"You sort of had this multiple-whammy of the hurricane, that orographic lifting from the mountains and this atmospheric river," he said. "Trillions of gallons of moisture coming in from the tropics."

PHOTO: An American flag sits in the floodwaters from Hurricane Helene in the Shore Acres neighborhood, Sept. 27, 2024, in St. Petersburg, Fla. (Mike Carlson/AP)

In hilly and mountainous terrains, rainfall tends to be focused in valleys and rivers, which explains the flash flooding event in Asheville, Francis said.

"No terrain is going to do well when you dump 15 to 30 inches of rain on it over a short period of time, which is exactly what happened in Appalachia," Shepherd said.

MORE: US Atlantic Coast becoming 'breeding ground' for rapidly intensifying hurricanes due to climate change, scientists say

The science behind the forecasting of Helene was near-perfect, especially with the amount of rain that the National Weather Service predicted days before, Shepherd said.

Communities may have been told about the impending storm but they aren't always prepared for the negative impacts, Kristina Dahl, a senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told ABC News.

PHOTO: In this Sept. 2, 2021 file photo, cars sit abandoned on the flooded Major Deegan Expressway following a night of extremely heavy rain from the remnants of Hurricane Ida in the Bronx borough of New York. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images, FILE)

Early warning systems need to be very transparent, with wide-reaching communication systems, so that people know a threat is coming and have time to prepare and evacuate, Dahl said.

MORE: Hurricane Helene: How climate change is making Florida's Big Bend more vulnerable to tropical threats

Local communities also need to prepare for all sorts of weather-related impacts by putting shelters in place and handing out hotel vouchers "so that things like personal finances don't present a barrier to getting yourself to safety," Dahl said.

Added Francis: "These inland communities, I think, are waking up to the fact that they are not immune to these tropical storms and these heavy precipitation events."

Destructive hurricanes like Helene highlight that catastrophic impacts from storms can extend far inland originally appeared on abcnews.go.com

MICHAEL PHILLIS and BRITTANY PETERSON

Wed, October 2, 2024

Ben Phillips, left, and his wife Becca Phillips scrape mud out of the living room of their home left in the wake of Hurricane Helene, Oct. 1, 2024, in Marshall, N.C.

(AP Photo/Jeff Roberson, File)

HENDERSONVILLE, N.C. (AP) — Hurricane Helene dumped trillions of gallons of water hundreds of miles inland, devastating communities nestled in mountains far from the threat of storm surge or sea level rise. But that distance can conceal a history of flooding in a region where water races into populated towns tucked into steep valleys.

“We almost always associate flood risk with hurricanes and coastal storm surge in Florida, Louisiana and Texas,” said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implication research at First Street, a company that analyzes climate risk. “We don’t think of western North Carolina and the Appalachian mountains as an area that has significant flood risk.”

More than 160 people have died across six Southeastern states. The flood waters carved up roads, knocked out cell service and pushed debris and mud into towns.

Parts of the Blue Ridge Mountains where fall colors are just starting to peek through were hit especially hard. In tourist-friendly Asheville, officials warned that it might take weeks to restore drinking water. Brownish orange mud stands out on river banks, a reminder of how high rivers swelled.

Hurricanes moving inland with heavy rainstorms have created disaster before. In 2004, for example, four people were killed in western North Carolina from a debris flow caused by as much of a foot (30.5 centimeters) of rain that fell from Hurricane Ivan.

It’s difficult to quickly determine the exact role climate change played in specific disasters like Hurricane Helene although one quick analysis found it likely increased rainfall totals in some areas.

Scientists say global warming is helping some big hurricanes become wetter.

Plus, a warmer atmosphere can hold more water, fueling intense rainstorms, although mountainous Appalachian terrain complicates the interaction between weather events and climate change, according to Jim Smith, a hydrologist at Princeton University.

Dave Marshall, executive pastor at First Baptist Church in Hendersonville, North Carolina, said he was “totally shocked” by the storm’s destruction that overwhelmed local services. On Tuesday he was overseeing a busy donation center that offered essentials such as propane and food, remarking that he had expected some rain and maybe a day or two without power.

“Nobody was prepared,” Marshall said. “We are shocked and devastated. Everybody knows a friend or family member that has lost a loved one.”

Porter, the climate risk researcher, said the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood maps used to determine the riskiest areas where certain homeowners are required to purchase flood insurance have their limitations. He said the maps consider a specific range of flooding and underestimate flood risk in some areas — and that the problem is especially pronounced in parts of Appalachia.

“It’s happening more and more often that we’re seeing these heavy precipitation events occur, exactly the type of events that this region is susceptible to,” Porter said, adding that flood zones on FEMA maps aren’t capturing these changing conditions.

FEMA recently updated how it prices flood insurance to factor in more types of flooding to accurately base cost on flood risk. The agency says flood maps are not meant to predict what areas will flood. Instead, they help define the riskiest areas for planning and insurance needs, FEMA said.

“Flooding events do not follow lines on a map. Where it can rain, it can flood,” said Daniel Llargues, a FEMA spokesperson.

Before Helene, federal forecasters told residents in western North Carolina flooding from the hurricane could be “one of the most significant weather events to happen” since 1916. That year, a pair of hurricanes within a week killed at least 80 people, and the community of Altapass received more than 20 inches of rain (50.8 centimeters) in a 24-hour span.

“This is not a big surprise,” said Smith. “But what happened in Helene happened in 1916.”

___

Phillis reported from St. Louis.

___

The Associated Press receives support from the Walton Family Foundation for coverage of water and environmental policy. The AP is solely responsible for all content. For all of AP’s environmental coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/climate-and-environment

How Helene's path created destruction in East Tennessee – and why reservoirs mattered

Daniel Dassow, Knoxville News Sentinel

Updated Tue, October 1, 2024

Heavy rainfall and widespread flooding made Hurricane Helene more than a generational storm for Southern Appalachia. But what characteristics of the region intensified the billions in damage and dozens of deaths hundreds of miles inland?

When the hurricane hit Western North Carolina and East Tennessee as a tropical storm Sept. 26-27, it caused a deadly interaction between the Appalachian mountains, small tributary streams and major rivers.

Reservoirs made a life-or-death difference in some spots, bottling up floodwater behind dams, even as those dams spilled record flows downstream and provoked a flood warning.

By the morning of Sept. 28, the town of Busick, North Carolina, near Mount Mitchell, had received more than 30 inches of rain. Rainfall across North Carolina broke records as Helene traveled north after battering Florida's Big Bend region as a Category 4 hurricane.

Runoff from the mountains caused three rivers that flow from North Carolina into Tennessee – the French Broad, Nolichucky and Pigeon – to burst far beyond their banks as they tore through towns like Erwin, Greeneville and Newport.

The rivers ran uncontrolled and unmoored from their banks for miles, carrying away houses, roads and bridges before converging and flowing into Douglas Lake.

“There are other areas that have flooding damage, numerous small creeks and tributaries, but that is the concentration of damage,” Tennessee Emergency Management Agency director Patrick Sheehan said, describing the rivers during a press conference on Sept. 30.

In East Tennessee, the rivers flow primarily through Cocke, Greene, Unicoi and Washington counties, though there also was extensive flooding in Carter, Hamblen, Hawkins and Johnson counties.

Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee declared a state of emergency in Tennessee on Sept. 27, and requested money and assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which the agency approved on Sept. 28.

The first round of federal assistance includes a 75% reimbursement for restoration work in Carter, Cocke, Greene, Hamblen, Johnson and Unicoi counties, and a 75% reimbursement for evacuation and shelter support in Hawkins and Washington counties. The remaining 25% will be a combination of local and state funds.

On Sept. 30, Lee wrote to the Biden administration again to request an expedited major disaster declaration, which has been approved in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina and South Carolina, but not Tennessee. The declaration would allow individuals in the eight counties to directly apply for federal aid, including grants for temporary housing or home repairs.

How Helene broke flooding records in East Tennessee

The day before Helene arrived in East Tennessee, the National Weather Service office in Morristown warned of the potential for two rounds of flooding. The first was Sept. 25-26, as the region received 2-4 inches of rain. The next was the tropical storm herself.

The first rain, a so-called "predecessor event," was caused by a band of moist air that came from the outer bands of the storm. It saturated the ground in parts of Tennessee and North Carolina, making runoff from Helene move faster and fuller.

As Helene moved across the Gulf of Mexico, it picked up more moisture. As it moved up the mountains, the uplift enhanced the amount of rainfall.

The heaviest rains in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina fell the night of Sept. 26 into the morning of Sept. 27. It was not long before the water came down the mountains and across the state line. Shortly after noon Sept. 27, as the Nolichucky swelled, 62 people, including 54 patients, were stranded on the roof of Unicoi County Hospital for hours.

They were eventually rescued by helicopters from across the region. Farther downstream at 11 p.m., the Nolichucky Dam near Greeneville withstood record flows nearly twice the amount that pours over Niagara Falls.

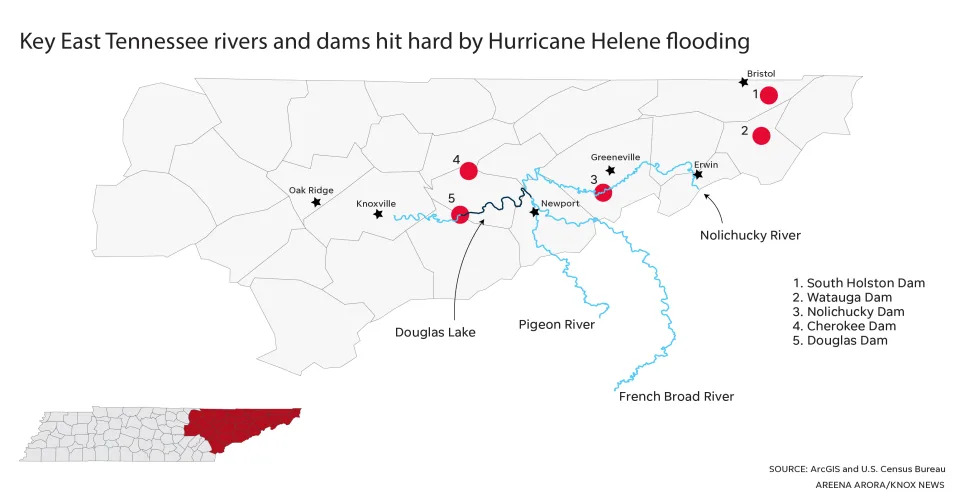

Key East Tennessee rivers and dams hit hard by Hurricane Helene flooding

Some counties in East Tennessee absorbed more than 10 inches of rain on Sept. 26-27.

Tennessee already is one of the rainiest states. In a normal year, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park receives between 55 inches and 85 inches of rain, depending on elevation.

Helene pushed the region beyond its breaking point. It was not just a generational storm, but a millennial one. The Nolichucky River watershed got rainfall "equal to about a 1-in-5,000-years rain event," TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said in an email Sept. 30.

The French Broad River in Newport swelled more than 13 feet higher than its flood stage in its largest flood in the area since 1867, according to the TVA update.

The Pigeon River in Newport was more than 20 feet higher than its flood stage, beating the previous record set in 1904. TVA's Watauga Dam broke its water level record by 3 feet, and the Watauga River was around 5 feet above its flood stage in the highest level in Elizabethton since 1940.

The storm led TVA to open spill gates on the Cherokee Dam for the first time in more than a decade. Typically, all water flowing through hydroelectric dams runs through turbines.

As it cleans up and restores the Nolichucky Dam, TVA is urging people to stay away. TVA Police will be on-site at the dam through the rest of the week. The utility expects commercial traffic along the Tennessee River to be interrupted for several days as it closes locks and sends massive amounts of water through the river.

Floodwaters from the Nolichucky River rage near Jackson Love Highway and Interstate 26 in Erwin, Tennessee, on Sept. 27. A Tennessee Valley Authority spokesperson said the Nolichucky River watershed absorbed so much rain from the landfall of Hurricane Helene that it equaled "about a 1-in-5,000-year rain event."More

Helene was more than a "500-year-event" for state infrastructure, said Will Reid, deputy commissioner and chief engineer of the Tennessee Department of Transportation. Fourteen state bridges are closed, and five are destroyed:

Greene County: State routes 107, 350 and 351

Unicoi County: Interstate 26 at mile marker 39.6

Washington County: State 81 (Alfred Taylor Bridge)

A section of Interstate 40 washed away near the Tennessee-North Carolina border.

TVA reservoirs store water from Helene

The Nolichucky and Pigeon rivers eventually flow into the French Broad River before Douglas Dam impounds the river to form Douglas Lake. As the crisis unfolded, reservoirs like Douglas Lake functioned as storage for floodwaters. The water level in the lake rose nearly 22 feet in three days.

But the water still needed to move through the river system. Through Oct. 1, the Tennessee Valley Authority spilled about 440,000 gallons of water per second through Douglas Dam. The National Weather Service office in Morristown issued a flood warning for parts of Knox and Sevier counties downstream of the dam until 7:30 p.m. on Oct. 1.

Douglas Lake, mostly in Jefferson County, and Watauga Lake, in Carter and Johnson counties, were the two reservoirs TVA relied on most to store water from Helene and move it downstream.

"Most of our tributaries have crested," Darrell Guinn, senior manager of TVA's River Forecast Center in Knoxville, said in a video update Sept. 30. "Some of those reservoirs still remain elevated, though. Watagua Reservoir (and) Douglas Reservoir continue to be elevated."

South Holston Lake and Watauga Lake stored much of the water not long after it poured into the northeastern corner of Tennessee through rivers and streams.

By contrast, the three rivers at the center of the flooding rushed with no storage through Cocke, Greene, Unicoi and Washington counties before reaching Douglas Lake.

Historic spilling from Douglas Dam led to some evacuations downstream, Tennessee Emergency Management Agency director Patrick Sheehan said in a news conference on Sept. 30.

The evacuations were small compared to those ordered in Newport when a dam on the Pigeon River was feared to have failed. Walters Dam, operated by Duke Energy, did not end up failing, though muddy and debris-filled water poured through it after record flooding.

TVA's first mission during the Great Depression was to build a system of dams that would prevent flooding and produce electricity for the rural South. It prevents around $309 million of flood damage annually.

"We are aware that these record releases are causing localized flooding on the Tennessee River," Brooks said. "However, the controlled releases are resulting in much lower river levels than would be possible if the dams weren’t in place."

Daniel Dassow is a growth and development reporter focused on technology and energy. Phone 423-637-0878. Email daniel.dassow@knoxnews.com.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: How Helene's path spelled destruction for East Tennessee towns

No comments:

Post a Comment