Associated Press

Mon, October 7, 2024

FILE - The Iron Gate Dam powerhouse and spillway are seen on the lower Klamath River near Hornbrook, Calif., March 2, 2020. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus, File)

HORNBROOK, Calif. (AP) — For the first time in more than a century, salmon are swimming freely along the Klamath River and its tributaries — a major watershed near the California-Oregon border — just days after the largest dam removal project in U.S. history was completed.

Researchers determined that Chinook salmon began migrating Oct. 3 into previously inaccessible habitat above the site of the former Iron Gate dam, one of four towering dams demolished as part of a national movement to let rivers return to their natural flow and to restore ecosystems for fish and other wildlife.

“It’s been over one hundred years since a wild salmon last swam through this reach of the Klamath River,” said Damon Goodman, a regional director for the nonprofit conservation group California Trout. “I am incredibly humbled to witness this moment and share this news, standing on the shoulders of decades of work by our Tribal partners, as the salmon return home."

The dam removal project was completed Oct. 2, marking a major victory for local tribes that fought for decades to free hundreds of miles (kilometers) of the Klamath. Through protests, testimony and lawsuits, the tribes showcased the environmental devastation caused by the four hydroelectric dams, especially to salmon.

Scientists will use SONAR technology to continue to track migrating fish including Chinook salmon, Coho salmon and steelhead trout throughout the fall and winter to provide "important data on the river’s healing process,” Goodman said in a statement. “While dam removal is complete, recovery will be a long process.”

Conservation groups and tribes, along with state and federal agencies, have partnered on a monitoring program to record migration and track how fish respond long-term to the dam removals.

As of February, more than 2,000 dams had been removed in the U.S., the majority in the last 25 years, according to the advocacy group American Rivers. Among them were dams on Washington state’s Elwha River, which flows out of Olympic National Park into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Condit Dam on the White Salmon River, a tributary of the Columbia.

The Klamath was once known as the third-largest salmon-producing river on the West Coast. But after power company PacifiCorp built the dams to generate electricity between 1918 and 1962, the structures halted the natural flow of the river and disrupted the lifecycle of the region’s salmon, which spend most of their life in the Pacific Ocean but return up their natal rivers to spawn.

The fish population dwindled dramatically. In 2002, a bacterial outbreak caused by low water and warm temperatures killed more than 34,000 fish, mostly Chinook salmon. That jumpstarted decades of advocacy from tribes and environmental groups, culminating in 2022 when federal regulators approved a plan to remove the dams.

Klamath River dam removal: before and after images show dramatic change

Cecilia Nowell

Tue, October 8, 2024

Water flowing down the Klamath River where the Copco 2 dam once stood in Siskiyou county, California.Photograph: Swiftwater Films/AP

Related: Salmon swim freely in Klamath River for first time in more than 100 years

With California’s Klamath Dam removal project finally completed, new before and after photos show the dramatic differences along the river with and without the dams. The photos were taken by Swiftwater Films, a documentary company chronicling the dam removal project – a two decade long fight that concluded 2 October.

“The tribally led effort to dismantle the dams is an expression of our sacred duty to maintain balance in the world,” Yurok tribal chairman Joseph L James said in a statement. “That is why we fought so hard for so long to tear down the dams and bring the salmon home.”

Between 1903 and 1962, the electric power company PacifiCorp built a series of dams along the Klamath River to generate electricity. The dams disrupted the river’s natural flow, and the migratory routes of its fish - including, most famously, the Chinook salmon.

By 2002, low water levels and high temperatures caused a bacterial outbreak in the river, killing more than 34,000 fish. The incident spurred tribes, like the Yurok and Karuk, and environmentalists to begin advocating for the removal of the river’s dams. In 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved a plan to remove four dams, which would allow the river to flow freely between Lake Ewauna in Oregon to the Pacific Ocean.

The Klamath Dam removal project, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) called “the world’s largest dam removal effort”, began in July 2023 and concluded more than a year later.

“This is a monumental achievement – not just for the Klamath River but for our entire state, nation and planet,” Gavin Newsom, the California governor, said in a statement. “By taking down these outdated dams, we are giving salmon and other species a chance to thrive once again, while also restoring an essential lifeline for tribal communities who have long depended on the health of the river.”

With the removal project completed on 2 October, scientists with the non-profit California Trout captured images of a 2.5-ft-long Chinook salmon migrating upstream for the first time in more than 100 years the very next day. Yet, scientists stress that it will take many more years to fully restore the ecosystems impacted by the dams.

Yukon River salmon runs remain low, but glimmers of improvement emerge

Mon, October 7, 2024

Yereth Rosen

Alaska Beacon

Salmon numbers in the Yukon River and its tributaries remained low this year, continuing a yearslong trend of struggles and harvest closures, but there were some positive signs, according to late-season information from Alaska and Canadian fisheries managers.

The fall run of chum salmon, which usually comes into the river system from mid-July to October, is the third lowest in a record that goes back to the 1970s, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game said in a Yukon River update issued on Wednesday. It is expected to be less than a quarter of the historic average of about 900,000 fish, the update said.

However, the summer run of chum salmon, which arrived in the river system earlier, was strong enough this year to allow some subsistence harvests, albeit with various gear restrictions and a requirement that any Chinook salmon that were caught be returned to the water alive.

Subsistence fishing was allowed in both state-managed segments and federally managed segments of the Yukon River system. And it was allowed during the period when the two runs were overlapping.

Subsistence harvests of chum salmon from the summer run were allowed last year as well, after the return emerged as better than forecast.

While runs are low – and are failing to meet treaty targets for returns into Canada — there has been some marginal improvement since the worst period a few years ago, official reports show

“We hit rock bottom in 2021 for all species on the Yukon,” said Christy Gleason, an Alaska Department of Fish and Game area biologist for the Yukon River region.

There were upticks even for the river’s troubled Chinook salmon runs. As of Sept. 19, 24,112 of the fish had reached the Alaska-Canada border, according to the most recent update from Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

That is well below the goal of a 71,000-fish target in the U.S.-Canada Yukon River Salmon Agreement. But it is well above the 14,752 Chinook that made it that far up the river last year and the 13,000 total predicted in this year’s preseason forecast, according to the update.

Fewer fall chum salmon had reached the Yukon River’s Canadian border than the total counted the same time last year, however, Fisheries and Oceans Canada said.

The summer chum salmon run, which generally returns in the period leading up to mid-July, has presented a brighter picture than the fall run, which generally starts in mid-July and runs to October.

The runs differ more in the timing of their entry into the Yukon River system, Gleason said.

The summer run is bigger and has a different age composition, she said. While both have a mix of 4-year-old and 5-year-old fish, the summer run’s mix is more even while the fall run typically tilts heavily to the age-4 fish, she said.

That is important because the age-4 fish are part of an age group that was especially hard-hit by poor ocean conditions triggered by warmer temperatures, she said.

Federal and state scientists have found evidence that extreme marine heatwaves in the Bering Sea from 2014 to 2019 harmed the chum salmon that were in the ocean at the time.

Problems in the saltwater environment appear to be lingering, including for the age-4 salmon that are the offspring of the poor 2020 return, Gleason said. “The ocean conditions aren’t really improving, so we’re not seeing improvement in the fall chum,” she said.

Another difference between the summer and fall chum runs concerns spawning areas. The fall chum spawn much farther upstream in the Yukon River system, including in the Canadian headwaters, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

An additional factor hindering recovery of the fall chum salmon run could stem from that reliance on Canadian headwaters

An abrupt change in Canadian river habitat, resulting from extreme glacial retreat in 2016, created a case of what scientists termed “river piracy” that wiped out an important chum-spawning site.

That event is tied to climate change. It happened when Canada’s Kaskawulsh Glacier retreated so much that it stopped sending water to one of the two rivers it previously fed. The Slims River, which fed the Yukon River system, was the loser, and the water was instead diverted to the Kaskawulsh River, which flows into the Gulf of Alaska rather than the Bering Sea.

Exclusive The Salmon’s Call Trailer Explores Indigenous Relationship With Wild Salmon

Alaska Beacon

Salmon numbers in the Yukon River and its tributaries remained low this year, continuing a yearslong trend of struggles and harvest closures, but there were some positive signs, according to late-season information from Alaska and Canadian fisheries managers.

The fall run of chum salmon, which usually comes into the river system from mid-July to October, is the third lowest in a record that goes back to the 1970s, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game said in a Yukon River update issued on Wednesday. It is expected to be less than a quarter of the historic average of about 900,000 fish, the update said.

However, the summer run of chum salmon, which arrived in the river system earlier, was strong enough this year to allow some subsistence harvests, albeit with various gear restrictions and a requirement that any Chinook salmon that were caught be returned to the water alive.

Subsistence fishing was allowed in both state-managed segments and federally managed segments of the Yukon River system. And it was allowed during the period when the two runs were overlapping.

Subsistence harvests of chum salmon from the summer run were allowed last year as well, after the return emerged as better than forecast.

While runs are low – and are failing to meet treaty targets for returns into Canada — there has been some marginal improvement since the worst period a few years ago, official reports show

“We hit rock bottom in 2021 for all species on the Yukon,” said Christy Gleason, an Alaska Department of Fish and Game area biologist for the Yukon River region.

There were upticks even for the river’s troubled Chinook salmon runs. As of Sept. 19, 24,112 of the fish had reached the Alaska-Canada border, according to the most recent update from Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

That is well below the goal of a 71,000-fish target in the U.S.-Canada Yukon River Salmon Agreement. But it is well above the 14,752 Chinook that made it that far up the river last year and the 13,000 total predicted in this year’s preseason forecast, according to the update.

Fewer fall chum salmon had reached the Yukon River’s Canadian border than the total counted the same time last year, however, Fisheries and Oceans Canada said.

The summer chum salmon run, which generally returns in the period leading up to mid-July, has presented a brighter picture than the fall run, which generally starts in mid-July and runs to October.

The runs differ more in the timing of their entry into the Yukon River system, Gleason said.

The summer run is bigger and has a different age composition, she said. While both have a mix of 4-year-old and 5-year-old fish, the summer run’s mix is more even while the fall run typically tilts heavily to the age-4 fish, she said.

That is important because the age-4 fish are part of an age group that was especially hard-hit by poor ocean conditions triggered by warmer temperatures, she said.

Federal and state scientists have found evidence that extreme marine heatwaves in the Bering Sea from 2014 to 2019 harmed the chum salmon that were in the ocean at the time.

Problems in the saltwater environment appear to be lingering, including for the age-4 salmon that are the offspring of the poor 2020 return, Gleason said. “The ocean conditions aren’t really improving, so we’re not seeing improvement in the fall chum,” she said.

Another difference between the summer and fall chum runs concerns spawning areas. The fall chum spawn much farther upstream in the Yukon River system, including in the Canadian headwaters, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

An additional factor hindering recovery of the fall chum salmon run could stem from that reliance on Canadian headwaters

An abrupt change in Canadian river habitat, resulting from extreme glacial retreat in 2016, created a case of what scientists termed “river piracy” that wiped out an important chum-spawning site.

That event is tied to climate change. It happened when Canada’s Kaskawulsh Glacier retreated so much that it stopped sending water to one of the two rivers it previously fed. The Slims River, which fed the Yukon River system, was the loser, and the water was instead diverted to the Kaskawulsh River, which flows into the Gulf of Alaska rather than the Bering Sea.

Exclusive The Salmon’s Call Trailer Explores Indigenous Relationship With Wild Salmon

Anthony Nash

Mon, October 7, 2024

(Image Credit: Firediva Productions)

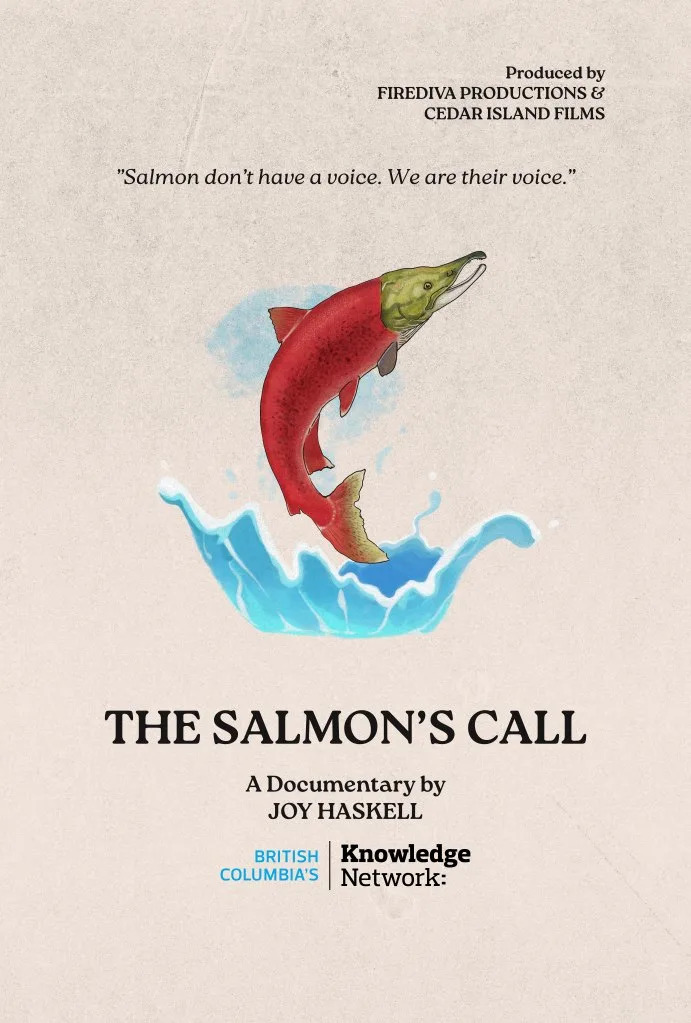

ComingSoon is debuting an exclusive The Salmon’s Call trailer, previewing the upcoming documentary exploring the spiritual and cultural relationship between salmon and the Indigenous people of British Columbia.

What happens in The Salmon’s Call trailer?

The Salmon’s Call trailer highlights the film’s exploration of wild salmon and the Indigenous people who share a connection to them. The film dives deep into the salmon’s cycle, the unique ways of catching and preserving the fish, and the hidden dangers of fish farms on the Pacific coast.

Check out the exclusive The Salmon’s Call trailer below (watch other trailers and clips):

The Salmon’s Call is directed by Joy Haskell, an Indigenous filmmaker and founder of Firediva Productions. The film will have its world premiere at the Red Nation International Film Festival in Los Angeles on Friday, November 15, 2024. More screenings, including future festival appearances and a broadcast date for the film’s premiere on Knowledge Network, will be announced in the future.

“The Salmon’s Call is a powerful documentary that explores the intricate spiritual and cultural relationship between wild salmon and Indigenous people that has lasted centuries,” reads the film’s official synopsis. “It is told through an Indigenous lens and gives a unique voice to a vital symbol of renewal, transformation, and resilience. The film takes viewers on a breathtaking journey with the Sockeye salmon from the West Coast waters of British Columbia, traversing the Fraser River, through the Chilcotin and the Stuart River (Nak’alkoh) and Stuart Lake (Nak’albun) situated in Northern British Columbia. Along this journey, we meet various members of the community from elders to youths as they share their rich connection to the salmon.”

(Image Credit: Firediva Productions)

The post Exclusive The Salmon’s Call Trailer Explores Indigenous Relationship With Wild Salmon appeared first on ComingSoon.net - Movie Trailers, TV & Streaming News, and (

No comments:

Post a Comment