Dangerous Hype: Big Tech’s Nuclear Lies

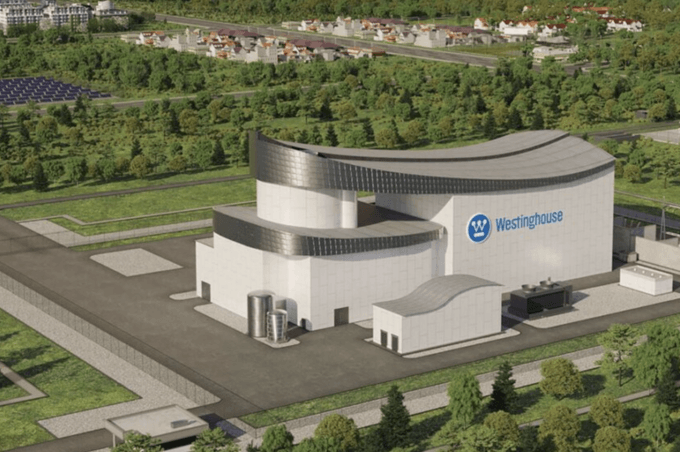

Small Modular Reactor, Credit Westinghouse.

In the last couple of months, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon, in that order, made announcements about using nuclear power for their energy needs. Describing nuclear energy using questionable adjectives like “reliable,” “safe,” “clean,” and “affordable,” all of which are belied by the technology’s seventy-year history, these tech behemoths were clearly interested in hyping up their environmental credentials and nuclear power, which is being kept alive mostly using public subsidies.

Both these business conglomerations—the nuclear industry and its friends and these ultra-wealthy corporations and their friends—have their own interests in such hype. In the aftermath of catastrophic accidents like Chernobyl and Fukushima, and in the face of its inability to demonstrate a safe solution to the radioactive wastes produced in all reactors, the nuclear industry has been using its political and economic clout to mount public relations campaigns to persuade the public that nuclear energy is an environmentally friendly source of power.

Tech giants like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, too, have attempted to convince the public they genuinely cared for the environment and really wanted to do their bit to mitigate climate change. In 2020, for example, Amazon pledged to reach net zero by 2040. Google went one better when its CEO declared that “Google is aiming to run our business on carbon-free energy everywhere, at all times” by 2030. Not that they are on any actual trajectory to meeting these targets.

Why are they making such announcements?

Greenwashing environmental impacts

The reasons underlying these companies investing in such PR campaigns is not hard to discern. There is growing awareness of the tremendous environmental impacts of the insatiable appetite for data from these companies, as well as the threat they pose to already inadequate efforts to mitigate climate change.

Earlier this year, the Wall Street company Morgan Stanley estimated that data centers will “produce about 2.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions through the end of the decade”. Climate scientists have warned that unless global emissions decline sharply by 2030, we are unlikely to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, a widely shared target. Even without the additional carbon dioxide emitted into the air as a result of data centers and their energy demand, the gap between current emissions and what is required is yawning.

But it is not just the climate. As calculated by a group of academic researchers, the exorbitant amounts of water required in the United States “to operate data centers, both directly for liquid cooling and indirectly to produce electricity” contribute to water scarcity in many parts of the country. This is the case elsewhere, too, and communities in countries ranging from Ireland to Spain to Chile are fighting plans to site data centers.

Then, there are the indirect impacts on the climate. Greenpeace documented, for example, that “Microsoft, Google, and Amazon all have connections to some of the world’s dirtiest oil companies for the explicit purpose of getting more oil and gas out of the ground and onto the market faster and cheaper.” In other words, the business models adopted by these tech behemoths depend on fossil fuels being used for longer and in greater quantities.

In addition to the increasing awareness about the impacts of data centers, one more possible reason for cloud companies to become interested in nuclear power might be what happened to cryptocurrency companies. Earlier this decade, these companies, too, found themselves getting a lot of bad publicity due to their energy demands and resulting emissions. Even Elon Musk, not exactly known as an environmentalist, talked about the “great cost to the environment” from cryptocurrency.

The environmental impacts of cryptocurrency played some part in efforts to regulate these. In September 2022, the White House put out a fact sheet on the climate and energy implications of Crypto-assets, highlighting President Biden’s executive order that called on these companies to reduce harmful climate impacts and environmental pollution. China even went as far as to banning cryptocurrency, and its aspirations to reducing its carbon emissions was one factor in this decision.

Crypto bros, for their part, did what cloud companies are doing now: make announcements about using nuclear power. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are now following that strategy to pretend to be good citizens. However, the nuclear industry has its reasons for welcoming these announcements and playing them up.

The state of nuclear power

Strange as it might seem to folks basing their perception of the health of the nuclear industry on mainstream media, that technology is actually in decline. The share of global electricity produced by nuclear reactors has decreased from 17.5% in 1996 to 9.15% in 2023, largely due to the high costs of and delays in building and operating nuclear reactors.

A good illustration is the Vogtle nuclear power plant in the state of Georgia. When the utility company building the reactor sought permission from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 2011, it projected a total cost of $14 billion, and “in-service dates of 2016 and 2017” for the two units. The plant became operational only this year, after the second unit came online in March 2024, at a total cost of at least $36.85 billion.

Given this record, it is not surprising that there are no orders for any more nuclear plants.

As it has been in the past, the nuclear industry’s answer to this predicament is to advance the argument that new nuclear reactor designs would address all these concerns. But that has, yet again, proved not to be the case. In November 2023, the flagship project of NuScale, the small modular reactor design promoted as the leading one of its kind, collapsed because of high costs.

Supporters of nuclear power are now using another time-tested tactic to promote the technology: projecting that energy demand will grow so much that no other source of power will be able to meet these needs. For example, UK energy secretary Ed Davey resorted to this gambit in 2013 when he said that the Hinkley Point C nuclear plant was essential to “keep the lights on” in the country.

Likewise, when South Carolina Electric & Gas Company made its case to the state’s Public Service Commission about the need to build two AP1000 reactors at its V.C. Summer site—this project was subsequently abandoned after over $9 billion was spent—it forecast in its “2006 Integrated Resource Plan” that the company’s energy sales would increase by 22 percent between 2006 and 2016, and by nearly 30 percent by 2019.

This is the argument that the growth in data centres, propped up in part by the hype about generative artificial intelligence, has allowed proponents of nuclear energy to put forward. It remains to be seen whether this hype about generative AI actually materializes into a long-term sustainable business: see, for example, Ed Zitron’s meticulously documented argument for why OpenAI and Microsoft are simply burning billions of dollars and why their business model might “simply not be viable”.

In the case of the V.C. Summer project, South Carolina Electric & Gas found that its energy sales actually declined by 3 percent compared to 2006 by the time 2016 rolled around. Of course, that did not matter, because shareholders had already received over $2.5 billion in dividends and company executives had received millions of dollars in compensation, according to Nuclear Intelligence Weekly, a trade publication.

One wonders which executives and shareholders are going to receive a bounty from this round of nuclear hype.

What about emissions?

Will the investments in nuclear power by companies like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon help reduce emissions anytime soon?

The project expected to have the shortest timeline is the restart of the Three Mile Island Unit 1 reactor, which Constellation Energy projects will be ready in 2028. But if the history of reactor commissioning is anything to go by, that deadline will come and go without any power flowing from it.

Restarting a nuclear plant that has been shutdown has never been done before. In the case of the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant in California, which hasn’t been shut down but was slated for decommissioning in 2024-25 till Governor Gavin Newsom did a volte-face, the Chair of the Diablo Canyon Independent Safety Committee explained why doing so was very difficult: “so many different programs and projects and so on have been put in place over the last half a dozen years predicated on that closure in 2024-25 and each one of those would have to be evaluated and some of them are okay, and some of them won’t be and some are going to be a real stretch and some are going to cost money and some of them aren’t going to be able to be done maybe”.

The cost of keeping Diablo Canyon open has been estimated by the plant’s owner at $8.3 billion and by independent environmental groups at nearly $12 billion. There are no reliable cost estimates for reopening Three Mile Island, but Constellation Energy, the plant’s owner, is already seeking a taxpayer-subsidized loan that would likely save the company $122 million in borrowing costs.

One must also remember that Microsoft already announced an agreement with Helion Energy, a company backed by billionaire Peter Thiele, to get nuclear fusion power by 2028. The chances of that happening are slim at best. In 2021, Helion announced that it had raised $500 million to build its fusion generation facility that would demonstrate “net electricity production” in three years, i.e., “in 2024”. That hasn’t happened so far. But going back further, one can see a similar and unfulfilled claim from 2014: then, the company’s chief executive had told the Wall Street Journal that the company hoped that its product would generate more energy than it would use “in the next three years” (i.e., in 2017). It is quite likely that Microsoft’s decision-makers knew of how unlikely it is that Helion will be able to supply nuclear fusion power by 2028. The publicity value is the most likely reason for announcing an agreement with Helion.

What about the small modular nuclear reactor designs—X-energy and Kairos—that Amazon and Google are betting on? Don’t hold your breath.

X-energy is an example of a high-temperature gas-cooled reactor design that dates back to the 1940s. There have been four reactors based on similar concepts that were operated commercially, two in Germany and two in the United States, respectively, and test reactors in the United Kingdom, Japan, and China. Each of these reactors proved problematic, suffering a variety of failures and unplanned shutdowns. The latest reactor with a similar design was built in China. Its performance leaves much to be desired: within about a year of being connected to the grid, its power output was reduced by 25 percent of the design power capacity, and even at this lowered capacity, it operated in 2023 with a load factor of just 8.5 percent.

Kairos, on the other hand, will be challenged by its choice of molten salts as coolant. These are chemically corrosive, and decades of search have identified no materials that can survive for long periods in such an environment without losing their integrity. The one empirical example of a reactor that used molten salts dates back to the 1960s, and this experience proved very problematic, both when the reactor operated and in the half-century thereafter, because managing the radioactive wastes produced before 1970 continued to be challenging.

Simply throwing money will not overcome these problems that have to do with fundamental physics and chemistry.

Just a dangerous distraction

Although Amazon, Google, and Microsoft claim to be investing in nuclear energy to meet the needs of AI, the evidence suggests that their real motive is to greenwash themselves.

Their investments are small and completely inadequate with relation to how much is needed to build a reactor. But their investments are also very small compared to the bloated revenues of these corporations. So, from the viewpoint of top executives, investing in nuclear power must seem a cheap way to reduce bad publicity about their environmental footprints. Unfortunately, “cheap” for them does not translate to cheap for the rest of us, not to mention the burden to future generations of human beings from worsening climate change and, possibly, increased production of radioactive waste that will stay hazardous for hundreds of thousands of years.

Because nuclear power has been portrayed as clean and a solution to climate change, announcements about it serve as a flashy distraction to focus public attention on. Meanwhile, these companies continue to expand their use of water and draw on coal and especially natural gas plants for their electricity. This is the magician’s strategy: misdirecting the audience’s attention while the real trick happens elsewhere. Their talk about investing in nuclear power also distracts from the conversations we should be having about whether these data centers and generative AI are socially desirable in the first place.

There are many reasons to oppose and organize against the wealth and power exercised by these massive corporations, such as their appropriation of user data to engage in what has been described as surveillance capitalism, their contracts with the Pentagon, and their support for Israel’s genocide and apartheid. Their investment into nuclear technology, and more importantly, hyping it up, offers one more reason. It is also a chance to establish coalitions between groups involved in very different fights.

A Nuclear Cautionary Tale

Artist rendition of Bill Gate’s proposed Natrium reactor in Wyoming.

A decade ago, NuScale, the Oregon-based small modular nuclear company born at Oregon State University, was on a roll. Promising a new era of nuclear reactors that were cheaper, easier to build and safer, their Star Wars-inspired artist renditions of a yet to be built reactor gleamed like a magic bullet.

As of last year, NuScale was the furthest along of any reactor design in obtaining Nuclear Regulatory Commission licensing and was planning to build the first small modular nuclear reactor in the United States. Its plan was to build it in Idaho to serve energy to a consortium of small public utility districts in Utah and elsewhere, known as UAMPS.

This home-grown Oregon company was lauded in local and national media. According to project backers, a high-tech solution to climate change was on the horizon, and an Oregon company was leading the way. It seemed almost too good to be true.

And it was.

Turns out, NuScale was a house of cards. The UAMPS project’s price tag more than doubled and the timeline was pushed back repeatedly until it was seven years behind schedule. Finally, UAMPS saw the writing on the wall and wisely backed out in November, 2023.

After losing their customer, NuScale’s stock plunged, it laid off nearly a third of its workforce, and it was sued by its investors and investigated for investor fraud. Then its CEO sold off most of his stock shares.

NuScale’s project is the latest in a long line of failed nuclear fantasies.

Why should you care? A different nuclear company, X-Energy, now in partnership with Amazon, wants to build and operate small modular nuclear reactors near the Columbia River, 250 miles upriver from Portland. Bill Gates’s darling, the Natrium reactor in Wyoming is also plowing ahead. Both proposals are raking in the Inflation Reduction Act and other taxpayer funded subsidies. The danger: Money and time wasted on these false solutions to the climate crisis divert public resources from renewables, energy efficiency and other faster, more cost-efficient and safer ways to address the climate crisis.

A recent study from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis concluded that small modular nuclear reactors are still too expensive, too slow to build and too risky to respond to the climate crisis.

While the nuclear industry tries to pass itself off as “clean,” it is an extremely dirty technology, beginning with uranium mining and milling which decimates Indigenous lands. Small modular nuclear reactors produce two to thirty times the radioactive waste of older nuclear designs, waste for which we have no safe, long-term disposal site. Any community that hosts a nuclear reactor will likely be saddled with its radioactive waste – forever. This harm falls disproportionately on Indigenous and low-income communities.

For those of us downriver, X-Energy’s plans to build at the Hanford Nuclear Site on the Columbia flies in the face of reason, as it would add more nuclear waste to the country’s largest nuclear cleanup site.

In Oregon, we have a state moratorium on building nuclear reactors until there is a vote of the people and a national waste repository. Every few years, the nuclear industry attempts to overturn this law at the Oregon Legislature, but so far it has been unsuccessful. This August, Umatilla County Commissioners announced they’ll attempt another legislative effort to overturn the moratorium. Keeping this moratorium is wise, given the dangerous distraction posed by the false solution of small modular nuclear reactors. Let’s learn from the NuScale debacle and keep our focus on a just transition to a clean energy future–one in which nuclear power clearly has no place.

This piece first appeared at Oregon Capital Chronicle.

Which Countries Are on the Brink of Going Nuclear?

Photo by Burgess Milner

Following Israel’s October 26, 2024, attack on Iranian energy facilities, Iran vowed to respond with “all available tools,” sparking fears it could soon produce a nuclear weapon to pose a more credible threat. The country’s breakout time—the period required to develop a nuclear bomb—is now estimated in weeks, and Tehran could proceed with weaponization if it believes itself or its proxies are losing ground to Israel.

Iran isn’t the only nation advancing its nuclear capabilities in recent years. In 2019, the U.S. withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), which banned intermediate-range land-based missiles, citing alleged Russian violations and China’s non-involvement. The U.S. is also modernizing its nuclear arsenal, with plans to deploy nuclear weapons in more NATO states and proposals to extend its nuclear umbrella to Taiwan.

Russia, too, has intensified its nuclear posture, expanding nuclear military drills and updating its nuclear policies on first use. In 2023, it suspended participation in the New START missile treaty, which limited U.S. and Russian deployed nuclear weapons and delivery systems, and stationed nuclear weapons in Belarus in 2024. Russia and China have also deepened their nuclear cooperation, setting China on a path to rapidly expand its arsenal, as nuclear security collaboration with the U.S. has steadily diminished over the past decade.

The breakdown of diplomacy and rising nuclear brinkmanship among major powers are heightening nuclear insecurity among themselves, but also risk spurring a new nuclear arms race. Alongside Iran, numerous countries maintain the technological infrastructure to quickly build nuclear weapons. Preventing nuclear proliferation would require significant collaboration among major powers, a prospect currently out of reach.

The U.S. detonated the first nuclear weapon in 1945, followed by the Soviet Union (1949), the UK (1952), France (1960), and China (1964). It became evident that with access to uranium and enrichment technology, nations were increasingly capable of producing nuclear weapons. Though mass production and delivery capabilities were additional hurdles, it was widely expected in the early Cold War that many states would soon join the nuclear club. Israel developed nuclear capabilities in the 1960s, India detonated its first bomb in 1974, and South Africa built its first by 1979. Other countries, including Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Sweden, Egypt, and Switzerland, pursued their own programs.

However, the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), enacted in 1968 to curb nuclear spread, led many countries to abandon or dismantle their programs. After the end of the Cold War and under Western pressure, Iraq ended its nuclear program in 1991, and South Africa, in a historic move, voluntarily dismantled its arsenal in 1994. Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Ukraine relinquished the nuclear weapons they inherited after the collapse of the Soviet Union by 1996, securing international security assurances in exchange.

Nuclear proliferation appeared to be a waning concern, but cracks soon appeared in the non-proliferation framework. Pakistan conducted its first nuclear test in 1998, followed by North Korea in 2006, bringing the count of nuclear-armed states to nine. Since then, Iran’s nuclear weapons program, initiated in the 1980s, has been a major target of Western non-proliferation efforts.

Iran has a strong reason to persist. Ukraine’s former nuclear arsenal might have deterred Russian aggression in 2014 and 2022, while Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, who dismantled the country’s nuclear program in 2003, was overthrown by a NATO-led coalition and local forces in 2011. If Iran achieves a functional nuclear weapon, it will lose the ability to leverage its nuclear program as a bargaining chipto extract concessions in negotiations. While a nuclear weapon will represent a new form of leverage, it would also intensify pressure from the U.S. and Israel, both of whom have engaged in a cycle of escalating, sometimes deadly, confrontations with Iran and its proxies over the past few years.

An Iranian nuclear arsenal could also ignite a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. Its relations with Saudi Arabia remain delicate, despite the 2023 détente brokered by China, and Saudi officials have previously indicated they would obtain their own nuclear weapon if Iran acquired them. Saudi Arabia gave significant backing to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, with the understanding that Pakistan could extend its nuclear umbrella to Saudi Arabia, or even supply the latter with one upon request.

Turkey, which hosts U.S. nuclear weapons through NATO’s sharing program, signaled a policy shift in 2019 when President Erdogan criticized foreign powers for dictating Turkey’s ability to build its own nuclear weapon. Turkey’s growing partnership with Russia in nuclear energy could meanwhile provide it with the enrichment expertise needed to eventually do so.

Middle Eastern tensions are not the only force threatening non-proliferation. Japan’s renewed friction with China, North Korea, and Russia over the past decade has intensified Tokyo’s focus on nuclear readiness. Although Japan developed a nuclear program in the 1940s, it was dismantled after World War II. Japan’s breakout period, however, remains measured in months, but public support for nuclear weapons remains low, given the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where nuclear bombings in 1945 killed more than 200,000 people.

In contrast, around 70 percent of South Koreans support developing nuclear weapons. South Korea’s nuclear program began in the 1970s but was discontinued under U.S. pressure. However, North Korea’s successful test in 2006 and its severance of economic, political, and physical links to the South in the past decade, coupled with the abandonment of peaceful reunification in early 2024, has again raised the issue in South Korea.

Taiwan pursued a nuclear weapons program in the 1970s, which similarly ended under U.S. pressure. Any sign of wavering U.S. commitment to Taiwan, together with China’s growing nuclear capabilities, could prompt Taiwan to revive its efforts. Though less likely, territorial disputes in the South China Sea could also motivate countries like Vietnam and the Philippines to consider developing nuclear capabilities.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has also had significant nuclear implications. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky recently suggested to the European Council that a nuclear arsenal might be Ukraine’s only deterrent if NATO membership is not offered. Zelensky later walked back his comments after they ignited a firestorm of controversy. Yet if Ukraine feels betrayed by its Western partners—particularly if it is forced to concede territory to Russia—it could spur some factions within Ukraine to attempt to secure nuclear capabilities.

The war has also spurred nuclear considerations across Europe. In December 2023, former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer endorsed a European nuclear deterrent. A Trump re-election could amplify European concerns over U.S. commitments to NATO, with France having increasingly proposed an independent European nuclear force in recent years.

Established nuclear powers are unlikely to welcome more countries into their ranks. But while China and Russia don’t necessarily desire this outcome, they recognize the West’s concerns are greater, with Russia doing little in the 1990s to prevent its unemployed nuclear scientists from aiding North Korea’s program.

The U.S. has also previously been blindsided by its allies’ nuclear aspirations. U.S. policymakers underestimated Australia’s determination to pursue a nuclear weapons program in the 1950s and 1960s, including covert attempts to obtain a weapon from the UK. Similarly, the U.S. was initially unaware of France’s extensive support for Israel’s nuclear development in the 1950s and 1960s.

Smaller countries are also capable of aiding one another’s nuclear ambitions. Argentina offered considerable support to Israel’s program, while Israel assisted South Africa’s. Saudi Arabia financed Pakistan’s nuclear development, and Pakistan’s top nuclear scientist is suspected of having aided Iran, Libya, and North Korea with their programs in the 1980s.

Conflicts involving nuclear weapons states are not without precedent. Egypt and Syria attacked nuclear-armed Israel in 1973, and Argentina faced a nuclear-armed UK in 1982. India and China have clashed over their border on several occasions, and Ukraine continues to resist Russian aggression. But conflicts featuring nuclear countries invite dangerous escalation, and the risk grows if a nation with limited conventional military power gains nuclear capabilities; lacking other means of defense or retaliation, it may be more tempted to resort to nuclear weapons as its only viable option.

The costs of maintaining nuclear arsenals are already steep. In 2023, the world’s nine nuclear-armed states spent an estimated $91.4 billion managing their programs. But what incentive do smaller countries have to abandon nuclear ambitions entirely, especially when they observe the protection nuclear weapons offer and witness the major powers intensifying their nuclear strategies?

Obtaining the world’s most powerful weapons may be a natural ambition of military and intelligence sectors, but it hinges on the political forces in power as well. In Iran, moderates could counterbalance hardliners, while continued support for Ukraine might prevent more nationalist forces from coming to power there.

Yet an additional country obtaining a nuclear weapon could set off a cascade of others. While larger powers are currently leading the nuclear posturing, smaller countries may see an opportunity amid the disorder. The limited support for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, in effect since 2021, as well as the breaking down of other international treaties, reinforces the lingering allure of nuclear arms even among non-nuclear states. With major powers in open contention, the barriers to nuclear ambitions are already weakening, making it ever harder to dissuade smaller nations from pursuing the ultimate deterrent.

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Rising Emissions From ‘Benign’ Technologies

Many people may naively assume that, in the era of climate change, the more modern the technologies, the smaller carbon footprint they will have. We have seen, however, that in one way or another, several technologies have gained currency by cleverly disguising their polluting nature behind apparently greener garb. Fracking for extraction of shale oil as in the US, or shifting to natural gas from oil for power generation and industrial uses in Europe, or promoting blue, grey or other such versions of hydrogen instead of hydrogen produced using renewable energy.

Much less is known, and even less appreciated, about the dangerous and rising emissions from what appears to the average person, as benign technologies that have transformed life in so many ways, and which look set to play an ever-greater role in the coming years.

Computing is one such area where companies, users and regulators are so focused on convenience, service delivery and lowering costs to consumers, that pollution in general and greenhouse gas emissions are scarcely even thought about.

Today’s laptops, tablets and smart phones have hundreds of times greater computing capacity as the room-size computers that took astronauts to land on the moon and brought them back. These devices take just an hour or so to fully charge and can be used for many hours after. People watch movies, ask questions and, nowadays, get answers not just from the search engine but from AI (artificial intelligence) services, personalised according to millions of bits of information on prior internet usage.

AI is becoming ubiquitous, used across the spectrum from science and technology, medicine and industry to cinema, the arts. Nobody thinks or worries about where large volumes of information users save are housed, they just access them with a simple click or swipe. Crypto-currencies are bought and sold with little thought given to just how these are created. Companies, which used to house large servers for their businesses, now use “cloud” services, where vast amounts of data are stored off-premises, invisible. It all seems like a magical, new world, without real environmental costs.

The “cloud” sounds wispy, other-worldly, even unreal. The reality is scary, dangerous and certainly not pretty.

Digital Emissions

AI services, crypto-currencies, processing of “big data,” such as consumer shopping behaviour, facial recognition, tracking of internet or social media messaging and so on, despite their apparently “invisible” nature, involve very real brick-and-mortar buildings housing enormous servers with huge computing capacity, all of which consume vast amounts of electricity, water to cool these systems, extra-large fans to aid in cooling and so on. More electricity means more emissions. Of course, if renewable energy is used, emissions would be less than with fossil energy, but that poses additional problems which we will deal with later.

It is hardly surprising that emissions from the digital sector have skyrocketed in recent years, when one considers that there were one billion internet-connected devices in the world in 2010, increasing rapidly to a projected 50 billion by 2025 and 100 billion by 2030. Emissions from the digital sector, now at roughly 3.5% of global emissions, have now overtaken those from aviation which are around 2.5%.

Crypto-currency “mining,” a complex computing process to “create” a roughly realistic “currency” to mimic -real money, is again a data and energy-hungry process that accounts for roughly 0.7% of global emissions.

It is roughly estimated that about half the emissions from the digital sector arise from the production side and half from the use. It is expected that, with the rapid rise in internet usage, especially through smart phones and with galloping deployment of AI, emissions from use of digital services will multiply manifold.

Problems in Estimating emissions

A big problem with more accurately estimating emissions from digital services is that reliable data are not forthcoming from the industry itself. No standardised metrics or estimation protocols have been evolved unlike for other industrial emissions sources.

Some information is available about the processing side. By and large, it is known that data centres where cloud computing, data storage and AI processing takes place, not to mention crypto-currency “mining,” are energy hungry, accounting for around 2% of global electricity consumption and roughly 1% of emissions, both these figures dating to before the recent explosion in AI services and widespread deployment of AI software and related hardware by the big internet companies.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated that electricity consumption from data centre and crypto-currency would reach about 3.5% of global electricity consumption, roughly equal to that of the fifth largest country, Japan. However, accurate assessment is made difficult by the business models used by different companies, for example outsourcing data-processing and cloud storage to other companies in different parts of the world.

However, there has been little study of emissions caused at the usage end. Some recent research at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and other places has sought to tackle this problem.

For example, creating one image using AI consumes as much electricity as fully charging a smart phone. A search using Chat GPT uses 10 times more electricity than a simple Google search which, incidentally, is getting difficult to do due to deployment of AI searches now increasingly becoming the default option on most smart phones. An AI software may consume 33 times more electricity than ordinary software. The World Economic Forum has estimated that the computer power dedicated to AI is doubling every 100 days.

The Big Five

The top five users of electricity, and largest emitters, in their data centres are, unsurprisingly, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Apple and Meta (Facebook). Amazon is by far the largest emitter, responsible for double that of the next biggest emitter, Apple. Most analysts leave out Amazon from their studies since their data usage and computing models are quite different from the others, making comparisons difficult.

An investigative study by The Guardian newspaper estimates that the emissions of these four, excluding Amazon, could actually be 7.62 times or 662% higher than their official reports have claimed, partly due to business outsourcing practices and partly due to non-transparent “renewable energy certificates or RECs,” similar to the notorious carbon offsets in climate change emissions control regimes.

Analysts say that while Apple and Meta use such “creative accounting” practices to show less emissions than are actually taking place, Google and Microsoft may be somewhat more transparent.

Google has set a “24/7” target, that is, has promised to run all its data centres on renewable energy 24 hours a day and seven days a week by 2030. Microsoft’s equivalent promise, called “100/100/0” is a pledge to use 100% renewable energy 100% of the time, buying-in 0 or no fossil-energy, again by 2030.

AI, Data Centres go Nuclear

But as the electricity demands rise steeply with AI deployment, the challenges are mounting for the data centres. Unlike most industrial, commercial or domestic users of electricity who have at least some day-night variations in electricity use, demand by data centres and global users remain more or less the same all day and around the year.

Pressure on the grid due this huge and mounting demand is posing serious problems. Data centres, whose power demand can be as high as 800-900 MWe, therefore, require their own reliable, round-the-clock, non-fossil electricity supply which cannot be assured by solar, wind or large hydro.

Enter nuclear power, an unanticipated scenario even five years ago.

Recently, a company called Constellation Power signed a 20-year power-purchase agreement with Microsoft for electricity supply to the latter from the infamous Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Unit 2 in the plant suffered the US’ worst nuclear accident when it had a partial meltdown of the reactor in 1979. The current agreement brings to life Unit 1, which had been shut down in 2019 due to doubts about its viability. In March, Amazon Web Services (AWS) contracted for 960 MW power from Talen Energy’s nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania.

There is a burst of activity around small modular (nuclear) reactors or SMR which is seeing a revival of interest, technology innovation and investment.

So now the future of the internet is to depend on nuclear power? Watch this space.

The writer is with the Delhi Science Forum and All India Peoples Science Network. The views are personal.

No comments:

Post a Comment