NAKBA 2.0

(RNS) — Alice Kisiya leads an interfaith effort to defend her family’s land against encroachment by Jewish settlers in the West Bank.

Israeli activists surround Alice Kisiya, center, as they try to enter her family's land, after the Palestinian family was forcefully evicted by Israeli settlers backed by soldiers who declared it a closed military area, in the West Bank town of Beit Jala, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Heather M. Surls

November 18, 2024

AMMAN, Jordan (RNS) — A group of Israeli Jews said Sabbath prayers on a late October Friday as the sun set in Al-Makhrour, a valley outside of Beit Jala in the West Bank. Nearby, Palestinian Muslims faced Mecca and said their own magrib prayers.

After the prayers the two groups sat together on a woven plastic mat along with a few Christians and others, to share a meal, roast marshmallows and get to know one another in a peaceful vigil, joined by another 40 people online. They had all come to support Alice Kisiya, 30, whose family had been forcibly evicted from their 1.25-acre plot in July by Jewish settlers, backed by the Israel Defense Forces.

Walking through an olive grove, her face illuminated by her phone’s light in the darkness, Kisiya told the online attendees that IDF soldiers had come by earlier, but, apparently taken aback by the sight of Jews, Muslims and Christians picnicking in the middle of a war, they drove away. Evil, she said, fears unity

“An interfaith community is what this society needs to be united and to be strong to achieve justice and peace,” said Kisiya, a Palestinian Christian with Israeli and French citizenship. “Sharing different backgrounds and beliefs and learning how to love and accept each other is the way to a new age where everyone can live in peace and harmony.”

RELATED: How the Israeli settlers movement shaped modern Israel

A vast majority of the land in Al-Makhrour, known locally as “Bethlehem’s heaven,” is owned by Palestinian Christians, who comprise less than 2% of the West Bank’s population. Save Al-Makhrour, an online community that supports the Kisiyas’ cause, frames the family’s case as a fight for Christian presence in the Holy Land.

The Kisiya property in the West Bank prior to structures being demolished.

(Photo courtesy Alice Kisiya)

“Christians in Israel and Palestine must stand together and not let families be picked off one by one,” read a Save Al-Makhrour statement. “Jews, Muslims and Christians must stand together for a vision of living in the Land alongside one another, thriving in freedom and equality.”

Civil Administration, Israel’s governing agency in the West Bank, began to threaten the Kisiyas shortly after Alice’s father, Ramzi, opened a restaurant on the land in 2002, she said. It hosted weddings and graduation parties as well as Christmas, Easter and Ramadan celebrations. The administration destroyed it in 2012, 2013 and 2015, always citing its lack of a building permit, though Alice Kisiya said the law didn’t require one since the restaurant, built from wood, was what she calls an “agricultural structure.” In 2019 the family’s home was jackhammered down too.

Kisiya said the family has legally owned the land since before Israel’s establishment in 1948, but in 2017, Himanuta, a subsidiary of the Jewish National Fund, claimed in court that it had bought the land in 1969. Recent reports by peace activists and in the Israeli press have called the JNF’s land acquisitions “dubious,” and the Kisiya family said a search of state archives turned up no sign of the transaction.

After their house was destroyed, the Kisiyas lived on the property in a tent until July 31, when a group of armed settlers supported by the Jewish National Fund barred the family’s entrance by installing a padlocked gate emblazoned with the Star of David. Asked for comment, the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, a unit of the Defense Ministry of Israel, cited the disputed acquisition and said it backed the lockout due to “friction,” COGAT told RNS, “between settlers and the Israeli citizen who was ruled not to own the place.”

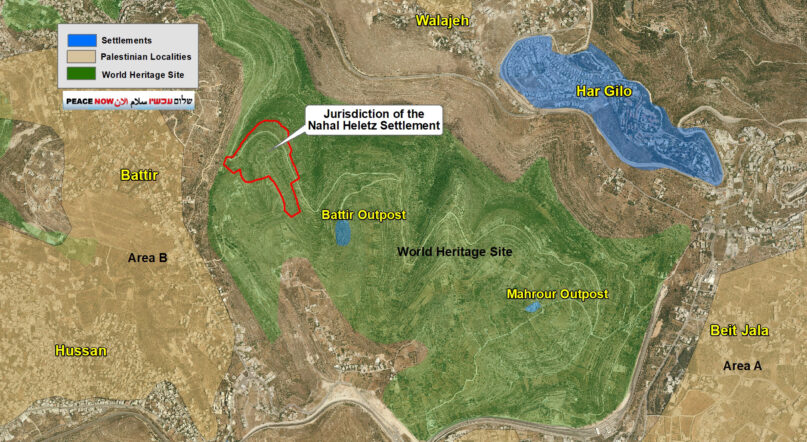

A couple of weeks later, Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich announced Israel’s plan to build Nahal Heletz, a settlement adjacent to Al-Makhrour that would connect settlements southwest of Bethlehem with Jerusalem. The settlement will sit in Battir, which, with Al-Makhrour, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. Currently, about 700,000 settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem live in settlements, which are considered illegal under international law.

“Christians in Israel and Palestine must stand together and not let families be picked off one by one,” read a Save Al-Makhrour statement. “Jews, Muslims and Christians must stand together for a vision of living in the Land alongside one another, thriving in freedom and equality.”

Civil Administration, Israel’s governing agency in the West Bank, began to threaten the Kisiyas shortly after Alice’s father, Ramzi, opened a restaurant on the land in 2002, she said. It hosted weddings and graduation parties as well as Christmas, Easter and Ramadan celebrations. The administration destroyed it in 2012, 2013 and 2015, always citing its lack of a building permit, though Alice Kisiya said the law didn’t require one since the restaurant, built from wood, was what she calls an “agricultural structure.” In 2019 the family’s home was jackhammered down too.

Kisiya said the family has legally owned the land since before Israel’s establishment in 1948, but in 2017, Himanuta, a subsidiary of the Jewish National Fund, claimed in court that it had bought the land in 1969. Recent reports by peace activists and in the Israeli press have called the JNF’s land acquisitions “dubious,” and the Kisiya family said a search of state archives turned up no sign of the transaction.

After their house was destroyed, the Kisiyas lived on the property in a tent until July 31, when a group of armed settlers supported by the Jewish National Fund barred the family’s entrance by installing a padlocked gate emblazoned with the Star of David. Asked for comment, the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, a unit of the Defense Ministry of Israel, cited the disputed acquisition and said it backed the lockout due to “friction,” COGAT told RNS, “between settlers and the Israeli citizen who was ruled not to own the place.”

A couple of weeks later, Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich announced Israel’s plan to build Nahal Heletz, a settlement adjacent to Al-Makhrour that would connect settlements southwest of Bethlehem with Jerusalem. The settlement will sit in Battir, which, with Al-Makhrour, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. Currently, about 700,000 settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem live in settlements, which are considered illegal under international law.

The Nahal Heletz settlement site, red, within a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the West Bank. (Image courtesy Peace Now)

For now, the Kisiyas have rented an apartment in nearby Al-Walaja, and Alice, who has worked as a journalist and fitness trainer, has resolved that it’s her turn to lead the family’s struggle for their land. Believing that God placed her where she is for a reason, she plans to proceed through patient, nonviolent resistance. “My parents taught me a lot (about) how to be strong and how not to lose hope, and that by following Jesus’ teaching we shall overcome evil,” she said.

Ofer Cassif, a member of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, said such land grabs have become routine under the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In September, the International Crisis Group reported that settlement activity and settler violence had increased dramatically since 2022, when Netanyahu’s far-right government came to power. The report noted more than 1,000 incidents of settler violence since the war in Gaza began, including 21 fatalities and 643 injuries, 1,300 Palestinians driven from their homes and thousands of acres of West Bank land stolen.

In February, Cassif, the only sitting Jewish lawmaker in the Hadash-Ta’al Party, was nearly expelled from the Knesset for supporting South Africa’s genocide case against Israel. Last week, the body agreed to suspend him for six months. Sometimes, he said, death threats force him to stay home. Yet Cassif, who identifies as an atheist, said he walks in the footsteps of the Jewish prophets, who stood firm against evil.

“For me to struggle for the rights of the Palestinians is because it’s just and justice is universal. … I need not be a Palestinian to support Palestinian liberation,” he said.

In late September, an interfaith group constructed the tiny Church of Nations near the Kisiyas’ land. Among those who worked on the building was Munther Amira, a Palestinian Muslim activist recently released from administrative detention in an Israeli prison. Volunteers framed the 260-square-foot structure with raw beams and walled it in with wooden sheeting painted to resemble stones. A cross, crescent and Star of David were painted on an inner wall.

That evening a vigil took place in the church as IDF soldiers stood watch nearby. Attendees included the Rev. Munther Isaac, a Lutheran pastor and academic dean of Bethlehem Bible College, as well as representatives from Rabbis for Human Rights and the World Council of Churches.

Two days later, the IDF returned with an excavator to disassemble the church.

The Church of Nations is constructed in late Sept. 2024, near the Kisiya family land in the West Bank. (Photo by Ahmad Al-Rajabi)

On Nov. 3, Kisiya was arrested and briefly detained after settlers on the land accused her of hitting a settler and stealing something. A video shows one of the settlers attacking Kisiya inside her car and attempting to strangle her.

“If it’s happening with Alice today, it might happen to my neighbor tomorrow, and the next day it’s me,” said Haytham Salameh, a Palestinian university student and volunteer medic who has joined Kisiya’s supporters. A resident of Bethlehem, Salameh had only encountered Israelis at border crossings and checkpoints until he came to the campfire picnic. “If it’s not going to be us who stand up with and for Alice, who’s it going to be?”

The morning after the picnic, Kisiya and a dozen others walked to her family’s land, but before they reached the Kisiyas’ road, the IDF met them.

Amira Musallam, Kisiya’s sister-in-law whose 9-year-old son will eventually inherit rights to the family land, said that to deter their entrance, the soldiers presented the group with a map and an order designating the land as a closed military zone — the third such order. Musallam said the documents actually applied to a piece of land about 4 kilometers away.

“We can’t do anything about it,” Musallam said. “They are the IDF, they are in control. … Even if we want to go to court, the court will not help because now everything is under the war emergency time.”

RELATED: Israeli settlers ‘expelled’ from Gaza in 2005 say it’s time to return

Kisiya remains hopeful, convinced she will return to her land. She is planning an international solidarity campaign in which participants will plant trees in the name of Al-Makhrour — a riff on the Jewish National Fund’s popular tree-planting project, whose proceeds go to support settlers and settlement building.

She also dreams of building Al-Makhrour’s first church to replace the Church of Nations, where Christians of all denominations will be able to unite in prayer. When settlers steal land, she said, she’ll ring the bell to remind them she is still there.

“We will keep our faith and will not give up,” Kisiya posted on Instagram on Oct. 7. “We will be united and defeat the evil. Love will win and the light will rise over the darkness. Justice and peace are not earned, they are made, and we the people together — Christians, Muslims and Jews and non-believers who believe in humanity — will achieve that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment