Threats to Free Expression in the Trump Era

Image by Curated.

I thought I was done with free speech. For nearly two decades, I reported on it for the international magazine Index on Censorship. I wrote a book, Outspoken: Free Speech Stories, about controversies over it. I even sang “I Like to Be in America” at the top of my lungs at an around-the-clock banned-book event organized by the Boston Coalition for Freedom of Expression after the musical “West Side Story” was canceled at a local high school because of its demeaning stereotypes of Puerto Ricans. I was ready to move on. I was done.

As it happened, though, free speech — or, more accurately, attacks on it — wasn’t done with me, or with most Americans, as a matter of fact. On the contrary, efforts to stifle expression of all sorts keep popping up like Whac-A-Mole on steroids. Daily, we hear about another book pulled from a school; another protest closed down on a college campus; another university president bowing to alumni pressure; another journalist suspended over a post on social media; another politically outspoken artist denied a spot in an exhibition; another young adult novel canceled for cultural insensitivity; another drag-queen story hour attacked at a library; another parent demanding control over how pronouns are used at school; another panic over the dangers lurking in AI; another op-ed fretting that even a passing acquaintance with the wrong word, picture, implication, or idea will puncture the fragile mental health of young people.

The list ranges from the ditzy to the draconian and it’s very long. Even conduct can get ensnared in censorship battles, as abortion has over what information healthcare providers are allowed to offer or what information crisis pregnancy centers (whose purpose is to dissuade women from seeking abortions) can be required to offer. Looming over it all, we just had an election brimming with repellent utterances financed by gobs of corporate money, which, the Supreme Court ruled in its 2010 Citizens United decision, is a form of speech protected by the First Amendment.

I suspect that if you live long enough, everything begins to seem like a rerun (as much of this has for me). The actors may change — new groups of concerned moms replace old groups who called themselves concerned mothers; antiracists police academic speech, when once it was anti-porn feminists who did it; AI becomes the new Wild West overtaking that lawless territory of yore, the World Wide Web — but the script is still the same.

It’s hard not to respond to the outrage du jour and I’m finding perspective elusive in the aftermath of the latest disastrous election, but I do know this: the urge to censor will continue in old and new forms, regardless of who controls the White House. I don’t mean to be setting up a false equivalence here. The Trump presidency already looks primed to indulge his authoritarian proclivities and unleash mobs of freelance vigilantes, and that should frighten the hell out of all of us. I do mean to point out that the instinct to cover other people’s mouths, eyes, and ears is ancient and persistent and not necessarily restricted to those we disagree with. But now, of all times, given what’s heading our way, we need a capacious view and robust defense of the First Amendment from all quarters — as we always have.

Make No Law

In a succinct 45 words, the First Amendment protects citizens from governmental restrictions on religious practices, speech, the press, and public airings of grievances in that order. It sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? But if a devil is ever in the details, it’s here, and the courts have been trying to sort those out over the last century or more. Working against such protections are the many often insidious ways to stifle expression, disagreement, and protest — in other words, censorship. Long ago, American abolitionist and social reformer Frederick Douglass said, “Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong that will be imposed upon them.” It was a warning that the ensuing 167 years haven’t proven wrong.

Censorship is used against vulnerable people by those who have the power to do so. The role such power plays became apparent in the last days of the recent election campaign when the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, at the insistence of their owners, declined to endorse anyone for president. Commentary by those who still care what the news media does ranged from a twist of the knife into the Post‘s Orwellian slogan, “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to assessments of the purpose or value of endorsements in the first place. These weren’t the only papers not to endorse a presidential candidate, but it’s hard not to read the motivation of their billionaire owners, Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong, as cowardice and self-interest rather than the principles they claimed they were supporting.

Newspapers, print or digital, have always been gatekeepers of who and what gets covered, even as their influence has declined in the age of social media. Usually, political endorsements are crafted by editorial boards but are ultimately the prerogative of publishers. The obvious conflict of interest in each of those cases, however, speaks volumes about the drawback of news media being in the hands of ultra-rich individuals with competing business concerns.

Journalists already expect to be very vulnerable during Donald Trump’s next term as president. After all, he’s called them an “enemy of the people,” encouraged violence against them, and never made a secret of how he resents them, even as he’s also courted them relentlessly. During his administration, he seized the phone records of reporters at the New York Times, the Washington Post, and CNN; called for revoking the broadcast licenses of national news organizations; and vowed to jail journalists who refuse to identify their confidential sources, later tossing editors and publishers into that threatened mix for good measure.

It can be hard to tell if Trump means what he says or can even say what he means, but you can bet that, with an enemies list that makes President Richard Nixon look like a piker, he intends to try to hobble the press in multiple ways. There are limits to what any president can do in that realm, but while challenges to the First Amendment usually end up in the courts, in the time the cases take to be resolved, Trump can make the lives of journalists and publishers miserable indeed.

Tinker, Tailor, Journalist, Spy

Among the threats keeping free press advocates up at night is abuse of the Espionage Act. That law dates from 1917 during World War I, when it was used to prosecute antidraft and antiwar activists and is now used to prosecute government employees for revealing confidential information.

Before Trump himself was charged under the Espionage Act for illegally retaining classified documents at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida after he left office, his Justice Department used it to prosecute six people for disclosing classified information. That included Wikileaks founder Julian Assange on conspiracy charges — the first time the Espionage Act had ever been used against someone for simply publishing such information. The case continued under President Biden until Assange’s plea deal this past summer, when he admitted guilt in conspiring to obtain and disclose confidential U.S. documents, thereby setting an unnerving precedent for our media future.

In his first term, Trump’s was a particularly leaky White House, but fewer leakers (or whistleblowers, depending on your perspective) were indicted under the Espionage Act then than during Barack Obama’s administration, which still holds the record with eight prosecutions, more than all previous presidencies combined. That set the tone for intolerance of leaks, while ensnaring journalists trying to protect their sources. In a notably durable case – it went on from 2008 to 2015 — James Risen, then a New York Times reporter, fought the government’s insistence that he testify about a confidential source he used for a book about the CIA. Although Obama’s Justice Department ultimately withdrew its subpoena, Risen’s protracted legal battle clearly had a chilling effect (as it was undoubtedly meant to).

Governments of all political dispositions keep secrets and seldom look kindly on anyone who spills them. It is, however, the job of journalists to inform the public about what the government is doing and that, almost by definition, can involve delving into secrets. Journalists as a breed are not easily scared into silence, and no American journalist has been found guilty under the Espionage Act so far, but that law still remains a powerful tool of suppression, open to abuse by any president. It has historically made self-censorship on the part of reporters, editors, and publishers an appealing accommodation.

Testing the Limits

Years ago, the legal theorist Thomas Emerson pointed to how consistently expression has indeed been restricted during dark times in American history. He could, in fact, have been writing about the response to protests over the war in Gaza on American campuses, where restrictions came, not from a government hostile to unfettered inquiry, but from institutions whose purpose is supposedly to foster and promote it.

After a fractious spring, colleges and universities around the country were determined to restore order. Going into the fall semester, they changed rules, strengthened punishments, and increased the ways they monitored expressive activities. To be fair, many of them also declared their intention to maintain a climate of open discussion and learning. Left unsaid was their need to mollify their funders, including the federal government.

In a message sent to college and university presidents last April, the ACLU recognized the tough spot administrators were in and acknowledged the need for some restrictions, but also warned that “campus leaders must resist the pressures placed on them by politicians seeking to exploit campus tensions to advance their own notoriety or partisan agendas.”

As if in direct rebuttal, on Halloween, the newly philosemitic House Committee on Education and the Workforce issued its report on campus antisemitism. Harvard (whose previous president Claudine Gay had been forced out, in part, because of her testimony to the committee) played a large role in that report’s claims of rampant on-campus antisemitism and civil rights abuses. It charged that the school’s administration had fumbled its public statements, that its faculty had intervened “to prevent meaningful discipline,” and that Gay had “launched into a personal attack” on Representative Elise Stefanik, a Republican committee member and Harvard graduate, at a Board of Overseers meeting. The report included emails and texts revealing school administrators tying themselves in knots over language that tried to appease everyone and ended up pleasing no one. The overarching tone of the report, though, was outrage that Gay and other university presidents didn’t show proper obeisance to the committee or rain sufficient punishment on their students’ heads.

Harvard continues to struggle. In September, a group of students staged a “study-in” at Widener, the school’s main library. Wearing keffiyehs, they worked silently at laptops bearing messages like “Israel bombs, Harvard pays.” The administration responded by barring a dozen protesters from that library (but not from accessing library materials) for two weeks, whereupon 30 professors staged their own “study-in” to protest the punishment and were similarly barred from the library.

The administration backed up its actions by pointing to an official statement from last January clarifying that protests are impermissible in several settings, including libraries, and maintained that the students had been forewarned. Moreover, civil disobedience comes with consequences. No doubt the protesters were testing the administration and, had they gotten no response, probably would have tried another provocation. As Harry Lewis, a former Harvard dean and current professor, told The Boston Globe, “Students will always outsmart you on regulating these things unless they buy into the principles.” Still, administrators had considerable leeway in deciding how to respond and they chose the punitive option.

Getting a buy-in sounds like what Wesleyan University President Michael Roth aimed for in a manifesto of sorts that he wrote last May, as students erected a protest encampment on his campus. Laying out his thinking on the importance of tolerating or even encouraging peaceful student protests over the war in Gaza, he wrote, “Neutrality is complicity,” adding, “I don’t get to choose the protesters’ messages. I do want to pay attention to them… How can I not respect students for paying attention to things that matter so much?” It was heartening to read.

Alas, the tolerance didn’t hold. In this political moment, it probably couldn’t. In September, Roth called in city police when students staged a sit-in at the university’s investment office just before a vote by its board of trustees on divesting from companies that support the Israeli military. Five students were placed on disciplinary probation for a year and, after a pro-divestment rally the next day, eight students received disciplinary charge letters for breaking a slew of rules.

Why Fight It

The right to free expression is the one that other democratic rights we hold dear rely on. Respecting it allows us to find better resolutions to societal tensions and interpersonal dissonance than outlawing words. But the First Amendment comes with inherent contradictions so, bless its confusing little heart, it manages to piss off nearly everyone sooner or later. Self-protection is innate, tolerance an acquired taste.

One of the stumbling blocks is that the First Amendment defends speech we find odious along with speech we like, ideas that frighten us along with ideas we embrace, jack-booted marches along with pink-hatted ones. After all, popular speech doesn’t need protection. It’s the marginal stuff that does. But the marginal might be — today or sometime in the future — what we ourselves want to say, support, or advocate.

And so, I return to those long-ago banned book readings, which culminated with everyone reciting the First Amendment together, a tradition I continued with my journalism students whenever I taught about press freedoms. Speaking words out loud is different from reading them silently. You hear and know them, sometimes for what seems like the first time. Maybe that’s why our communal celebration of the First Amendment seemed to amuse, embarrass, and impress the students in unequal measure. I think they got it, though.

I recognize that this kind of exhortation is many planks short of a strategy, but it’s a place to start, especially in the age of Donald Trump, because, in the end, the best reason to embrace and protect the First Amendment is that we will miss it when it’s gone.

This piece first appeared on TomDispatch.

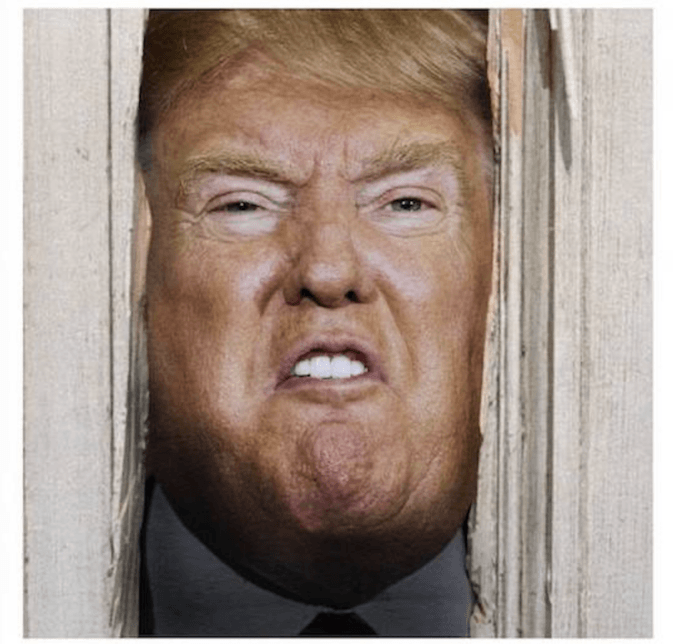

Trump’s House of Horrors

Art by Nick Roney

“The advantage I have now is I know everybody. I know people. I know the good, the bad, the stupid, the smart.”

– Donald Trump, Time Magazine, April 2024

One of the most important powers of the presidency is the power of appointment. There are several hundred federal agencies, and the president has the power to make several thousand appointments to these agencies as well as to his cabinet and various executive branch institutions.

Donald Trump’s first term was marred by several appointees that had to be removed in the first year. National Security Advisor Michael Flynn was removed in less than a month for lying to the FBI and Vice President Pence. Ethics charges led to the removal of several cabinet officials, including the Secretary for Health and Human Services; the head of the Environmental Protection Administration; the Secretary of the Interior, and the Secretary of the Veterans Administration. The Secretary of State was fired in his first year, and the Attorney General either resigned or was fired as well.

And there were those who resigned less than two years in, and lambasted Trump soon after. UN Ambassador Nikki Haley described Trump as “just toxic” and “unhinged,” “lacking moral clarity.” Chief of Staff John Kelly said that he had never met anyone more unscrupulous than Donald Trump. Attorney General Bill Barr and national security adviser John Bolton were similarly critical. Of Trump’s highest level appointments, only four of the top 44 supported his run for a second term.

The appointments for Trump’s second term can’t be attributed to recommendations from outsiders; they are far worse and more dangerous than those made in the first term, when Trump could at least say he appointed people he didn’t really know first hand. Thus far, Trump’s appointees lack the skills and the experience that their particular assignments requirement. They truly constitute a house of horrors.

The worst and most dangerous appointment is Pete Hegseth as secretary of defense. Various experts would tell you that running the Department of Defense is the most challenging management job in the world. It has nearly 3 million employees, including the uniformed military the world over; civilians, and the National Guard. The Pentagon’s budget is more than $900 billion a year, and climbing. It was Hegseth who convinced Trump to pardon war criminals in his first term. Hegseth, a Fox News anchor on its weekend broadcasts, could not be more unqualified, and his confirmation process will test the mettle and courage of the new Senate Majority Leader, John Thune.

Tulsi Gabbard as Director of National Intelligence is another cause for concern. In 2017, Gabbard met with Syrian President Bashar al Assad, and defended his attacks on Syrian civilians. She even challenged the intelligence that documented Assad’s use of chemical weapons against civilian communities. More recently, Gabbard said that media freedom in Russia is “not so different” from that in the United States. Gabbard was reportedly placed on a Transportation Security Administration (TSA) watchlist known as “Quiet Skies” this year, which allows federal air marshals to follow U.S. citizens and collect information on their behavior.

The appointment of Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) as Attorney General speaks for itself. Gaetz can be counted on to wield the Justice Department against Trump’s political enemies, and Gaetz will also move swiftly to end the two federal criminal cases against Trump.

Lack of experience appears to be the major qualification for most of the appointments. Kristi Noem has been named to head the Department of Homeland Security, which has a $60 billion budget and a work force of 234,000. It is responsible for the Secret Service, the Coast Guard, and Federal Emergency Management Agency. Elise Stefanik has no background in diplomacy or international relations, but she will be the UN ambassador. Her greatest qualification appears to be her contempt for the United Nations, which is how Nikki Haley got the job in Trump’s first term. Of course, the same could be said for UN ambassadors such as John Bolton in George W. Bush’s first term or Jeane Kirkpatrick in Ronald Reagan’s first term.

The list goes on. John Ratcliff, who politicized intelligence in Trump’s first term as the Director of National Intelligence, will become the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Lee Zelden, who has no experience with climate or energy issues, will be the administrator at the Environmental Protection Agency. Mike Huckabee, who says there is no such thing as a Palestinian and that illegal Israeli settlements on the West Bank are actually legal Israeli communities, will be ambassador to Israel. Stephen Miller, on the far right wing of the political spectrum, will be deputy chief of staff in the White House for policy, particularly immigration policy. Miller favors mass deportation as does the new border czar Tom Homan, who favored family separation policy as a way to deter immigration when he served as acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

One worrisome feature of the new appointments in the national security field is their hostility to China. This is true for the new national security adviser, Mike Waltz, who introduced legislation to rename Dulles International Airport as (you guessed it) Trump International. The expected secretary of state, Mario Rubio, is a China Hawk as well as an Iran-Cuba-Venezuela Hawk. The Washington Post has already endorsed the appointment of Rubio, believing that a tough policy toward China will get concessions from Xi Jinping. We’re certain to have a trade war with China in the near term, but perhaps we shouldn’t rule out war itself.

All of these appointments pale next to the naming of Hegseth to the Pentagon. There have been 30 secretaries of defense since the creation of the Department of Defense in 1947. Only a handful of these secretaries truly succeeded: George Marshall in the Truman administration; Harold Brown in the Carter administration; and Bill Perry in the Clinton administration. Some of the most knowledgeable failed such as Les Aspin, whose health worsened in his short tour as secretary of defense. The first secretary of defense, James Forrestal, committed suicide soon after leaving the Pentagon post. Bob Gates and Leon Panetta simply surrendered to the uniformed military and didn’t act as civilian leaders of the Department of Defense. The fact that Trump has talked of using the Insurrection Act to involve the uniformed military in dealing with domestic violence makes the Hegseth appointment particularly threatening.

Political loyalty is obviously the key to Trump’s selection process. This is certainly true for Ratcliff and Waltz in the national security field; for Stefanik in the diplomacy arena; and for Miller and Homan in the area of immigration. And it could get worse before it gets worse because there has been no mention thus far of Jeffrey Clark, Kash Patel, Matthew Whitaker or Richard Grenell, who have been more than loyal to Trump. Stay tuned to this space.

No comments:

Post a Comment