WHITE SUPREMACY

The criminal legal system isn’t designed to deliver justice for Jordan Neely. Here’s how we can.

By Alex S. Vitale ,

December 12, 2024

Daniel Penny is seen arriving at court on December 9, 2024,

in New York, New York. MEGA / GC Images

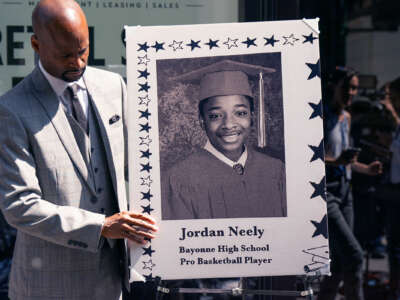

ANew York City jury on Monday found Daniel Penny not guilty of the crime of killing Jordan Neely in a New York subway car in 2023.

Prosecutors attempted to convict Penny on the charge of reckless endangerment for using a fatal chokehold to subdue Neely. Penny, a military veteran, claimed that Neely’s death was inadvertent and unintentional. Mayor Eric Adams, who previously defended Penny’s actions, said that Neely’s death was unfortunate, but has taken no steps to improve the systems that left him homeless and without adequate mental health care. Following the trial, conservative politicians echoed their calls for Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg to resign over what they baselessly claim to be a malicious and politically driven prosecution of a well-meaning good Samaritan.

In a press conference following the verdict, Neely’s father, Andre Zachary, said that “the system is rigged” and asked, “What are we going to do, people?” This is the starting point for a conversation about how to achieve some semblance of justice in cases where those with power use violence against the vulnerable in the name of “law and order,” be they citizens, the police or self-appointed vigilantes like Kyle Rittenhouse or George Zimmerman.

ANew York City jury on Monday found Daniel Penny not guilty of the crime of killing Jordan Neely in a New York subway car in 2023.

Prosecutors attempted to convict Penny on the charge of reckless endangerment for using a fatal chokehold to subdue Neely. Penny, a military veteran, claimed that Neely’s death was inadvertent and unintentional. Mayor Eric Adams, who previously defended Penny’s actions, said that Neely’s death was unfortunate, but has taken no steps to improve the systems that left him homeless and without adequate mental health care. Following the trial, conservative politicians echoed their calls for Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg to resign over what they baselessly claim to be a malicious and politically driven prosecution of a well-meaning good Samaritan.

In a press conference following the verdict, Neely’s father, Andre Zachary, said that “the system is rigged” and asked, “What are we going to do, people?” This is the starting point for a conversation about how to achieve some semblance of justice in cases where those with power use violence against the vulnerable in the name of “law and order,” be they citizens, the police or self-appointed vigilantes like Kyle Rittenhouse or George Zimmerman.

It is clear that the criminal legal system, even when utilized by so-called progressive prosecutors like Alvin Bragg, is not capable of producing real justice on behalf of those most in need of it. This system was not designed to provide justice for the unhoused, undocumented, unemployed or uninsured.

Supporters of the punishment bureaucracy tell us over and over that we must prioritize investments in policing, courts and prisons to protect the vulnerable, but time and time again we see these systems fail in that supposed mission. In fact, that system itself perpetrates tremendous amounts of harm in the form of violence, sexual assaults and homicides: Police alone are responsible for a third of all killings by strangers. Prison and jail guards engage in widespread brutality, torture and sexual violence, often with impunity. Police solve fewer than half of all violent crimes reported to them and even when they clear cases, their ability to produce actual public safety remains elusive.

Related Story

The US Failed Jordan Neely and Banko Brown Long Before They Were Murdered

As housing-insecure Black youth, Banko Brown and Jordan Neely needed care. Instead, they were policed and criminalized.

By Subini Annamma , Jyoti Nanda , Brian Cabral , Jamelia Morgan ,

TruthoutMay 17, 2023

If, instead of accepting the naive fantasy that the criminal legal system exists to protect us, we acknowledge that its primary mission is the maintenance of a system of economic inequality and political disempowerment, then its seeming failures make more sense. The system is, in fact, rigged. It is not capable of providing justice because it wasn’t designed for that purpose. Given this fact, we should stop looking to that system to help us. We should quit expecting courts to rescue us from abuse that benefits the powerful.

We must instead develop alternative systems of accountability that set the stage for a more expansive and powerful form of justice. We can look to a variety of community-centered models for uncovering the truth of events, properly measuring the harms that have been suffered and outlining real strategies of prevention so that others don’t experience the same fate. When the survivors of violence are asked about what they want as justice, the emphasis is often on finding out the truth and preventing harm happening to others.

Ideally, a transformative justice approach would involve victims, perpetrators and the community in a process of getting to the root of violence, addressing the needs of survivors, and developing systems of individual and structural prevention. Such a process requires the voluntary and meaningful participation of those accused of committing harm. This is not always easy or even possible. Some offenders will refuse such a process, but it is still important to hold it out as an alternative, even in cases where prosecutors claim to be trying to hold those with power and privilege to account.

The criminal legal system is, in fact, rigged. It is not capable of providing justice because it wasn’t designed for that purpose.

When prosecutors offer punishment as the tool of accountability, they play into the logic that punishment equals justice. And since the process is entirely punitive in its orientation, it makes martyrs of those it pursues. When defendants are found guilty, such as in the Trump verdict, the convictions become fodder for claims of politically motivated prosecutorial overreach. When defendants are found not guilty, the process turns those acquitted into potential heroes for the extreme right as in the case of Kyle Rittenhouse. So we need a system which seeks to tell the truth about what happened and makes clear that the community views what happened as dangerous, unnecessary and unjust. By telling the truth about what happened and offering the possibility of reconciliation, we make it harder for the discourses of martyrdom to take hold.

There are organizations across the country that specialize in transformative justice processes that attempt to get to the root of harmful behavior and chart a path forward such as the California-based Ahimsa Collective, Project NIA in Chicago and Seattle’s Collective Justice. These groups address both the needs of the individuals directly involved and the larger community, with an eye toward both short-term and long-term transformations.

Another model to consider is publicly controlled truth commissions. While criminal trials are aimed at achieving individual accountability in the form of punishment, truth commissions are focused on describing patterns of harm, recommending policies to prevent the repetition of such abuses and proposing measures to make reparations for past wrongs.

In this case, such a commission could be constituted by organizations connected to those most vulnerable to the kind of violence inflicted on Neely such as VOCAL-NY, whose members and leaders have experienced homelessness, incarceration, mental illness and drug involvement. They could pull together a panel to hear testimony about what happened, the individual and structural factors that caused it, and proposals for prevention and reparations.

One recent example of this is the efforts of We Charge Genocide in Chicago. This group was inspired by the efforts of civil rights leaders in the 1950s to document and expose racist violence in the U.S. on an international stage. Starting in 2014, the effort was designed to expose the impact of brutal policing of young people of color there. It was a tool for organizing young people and to get their own communities to see more clearly the challenges they faced in their everyday lives from police and a host of other institutional actors that too often viewed them as already guilty of something. Through a process of public hearings and information gathering, We Charge Genocide exposed the horrific practices of the Chicago police, including the presence of a police torture center used to extract confessions and otherwise terrorize people of color. Their efforts both shone a light on the harms young people experienced and outlined a series of restorative measures that could lead to a better future for them and their communities. This process ultimately contributed to the reparations agreement with the City of Chicago that created new youth resources and memorialized what had happened by funding the Chicago Torture Justice Center.

Ideally, a transformative justice approach would involve victims, perpetrators and the community in a process of getting to the root of violence.

There are several underlying causes that could be explored by a truth commission focused on the killing of Jordan Neely. For example, what role did Penny’s military service play? Did his military training instill in him an ethos of violent “threat neutralization,” or what sociologist Michael Sierra-Arevalo calls the “danger imperative” in the context of policing? Did Penny learn both the technique of chokeholds and the valorization of violent interventions?

Neely was repeatedly failed by the inadequacies of mental health services in New York City. Even Mayor Adams has decried the lack of service (while doubling down on morespending for police). A truth commission could ask: What services had Neely received (if any), and how were they inadequate? What kinds of models would be better?

Neely was unhoused, which probably contributed to both his mental health challenges and his frequent presence on the subway. Short-term treatment placements failed to move him toward stable supportive housing. How can this be corrected? What kinds of supportive housing would have best served his needs? What is preventing the development of this kind of housing?

What has the impact of Neely’s death been on Neely’s family and friends as well as the larger community? What could be done to help address their trauma and sense of insecurity?

We are not in a position to compel the state to seek justice on our terms. Instead, we must lead by example and build up the tools and capacities to rethink how we achieve justice in our own lives and in society at large. As long as we continue to rely on the punishment bureaucracy, we undermine those capacities and surrender the terrain of justice to institutions that have never had our best interests at heart.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Alex S. Vitale is professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center and author of The End of Policing.

If, instead of accepting the naive fantasy that the criminal legal system exists to protect us, we acknowledge that its primary mission is the maintenance of a system of economic inequality and political disempowerment, then its seeming failures make more sense. The system is, in fact, rigged. It is not capable of providing justice because it wasn’t designed for that purpose. Given this fact, we should stop looking to that system to help us. We should quit expecting courts to rescue us from abuse that benefits the powerful.

We must instead develop alternative systems of accountability that set the stage for a more expansive and powerful form of justice. We can look to a variety of community-centered models for uncovering the truth of events, properly measuring the harms that have been suffered and outlining real strategies of prevention so that others don’t experience the same fate. When the survivors of violence are asked about what they want as justice, the emphasis is often on finding out the truth and preventing harm happening to others.

Ideally, a transformative justice approach would involve victims, perpetrators and the community in a process of getting to the root of violence, addressing the needs of survivors, and developing systems of individual and structural prevention. Such a process requires the voluntary and meaningful participation of those accused of committing harm. This is not always easy or even possible. Some offenders will refuse such a process, but it is still important to hold it out as an alternative, even in cases where prosecutors claim to be trying to hold those with power and privilege to account.

The criminal legal system is, in fact, rigged. It is not capable of providing justice because it wasn’t designed for that purpose.

When prosecutors offer punishment as the tool of accountability, they play into the logic that punishment equals justice. And since the process is entirely punitive in its orientation, it makes martyrs of those it pursues. When defendants are found guilty, such as in the Trump verdict, the convictions become fodder for claims of politically motivated prosecutorial overreach. When defendants are found not guilty, the process turns those acquitted into potential heroes for the extreme right as in the case of Kyle Rittenhouse. So we need a system which seeks to tell the truth about what happened and makes clear that the community views what happened as dangerous, unnecessary and unjust. By telling the truth about what happened and offering the possibility of reconciliation, we make it harder for the discourses of martyrdom to take hold.

There are organizations across the country that specialize in transformative justice processes that attempt to get to the root of harmful behavior and chart a path forward such as the California-based Ahimsa Collective, Project NIA in Chicago and Seattle’s Collective Justice. These groups address both the needs of the individuals directly involved and the larger community, with an eye toward both short-term and long-term transformations.

Another model to consider is publicly controlled truth commissions. While criminal trials are aimed at achieving individual accountability in the form of punishment, truth commissions are focused on describing patterns of harm, recommending policies to prevent the repetition of such abuses and proposing measures to make reparations for past wrongs.

In this case, such a commission could be constituted by organizations connected to those most vulnerable to the kind of violence inflicted on Neely such as VOCAL-NY, whose members and leaders have experienced homelessness, incarceration, mental illness and drug involvement. They could pull together a panel to hear testimony about what happened, the individual and structural factors that caused it, and proposals for prevention and reparations.

One recent example of this is the efforts of We Charge Genocide in Chicago. This group was inspired by the efforts of civil rights leaders in the 1950s to document and expose racist violence in the U.S. on an international stage. Starting in 2014, the effort was designed to expose the impact of brutal policing of young people of color there. It was a tool for organizing young people and to get their own communities to see more clearly the challenges they faced in their everyday lives from police and a host of other institutional actors that too often viewed them as already guilty of something. Through a process of public hearings and information gathering, We Charge Genocide exposed the horrific practices of the Chicago police, including the presence of a police torture center used to extract confessions and otherwise terrorize people of color. Their efforts both shone a light on the harms young people experienced and outlined a series of restorative measures that could lead to a better future for them and their communities. This process ultimately contributed to the reparations agreement with the City of Chicago that created new youth resources and memorialized what had happened by funding the Chicago Torture Justice Center.

Ideally, a transformative justice approach would involve victims, perpetrators and the community in a process of getting to the root of violence.

There are several underlying causes that could be explored by a truth commission focused on the killing of Jordan Neely. For example, what role did Penny’s military service play? Did his military training instill in him an ethos of violent “threat neutralization,” or what sociologist Michael Sierra-Arevalo calls the “danger imperative” in the context of policing? Did Penny learn both the technique of chokeholds and the valorization of violent interventions?

Neely was repeatedly failed by the inadequacies of mental health services in New York City. Even Mayor Adams has decried the lack of service (while doubling down on morespending for police). A truth commission could ask: What services had Neely received (if any), and how were they inadequate? What kinds of models would be better?

Neely was unhoused, which probably contributed to both his mental health challenges and his frequent presence on the subway. Short-term treatment placements failed to move him toward stable supportive housing. How can this be corrected? What kinds of supportive housing would have best served his needs? What is preventing the development of this kind of housing?

What has the impact of Neely’s death been on Neely’s family and friends as well as the larger community? What could be done to help address their trauma and sense of insecurity?

We are not in a position to compel the state to seek justice on our terms. Instead, we must lead by example and build up the tools and capacities to rethink how we achieve justice in our own lives and in society at large. As long as we continue to rely on the punishment bureaucracy, we undermine those capacities and surrender the terrain of justice to institutions that have never had our best interests at heart.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Alex S. Vitale is professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center and author of The End of Policing.

No comments:

Post a Comment