When it comes to venerating St. Thomas Aquinas, are two heads better than one?

(RNS) — In his triple jubilee year, the great Catholic theologian has been celebrated this year in academic conferences and expositions of his relics — resurrecting an old controversy about where his true head lies.

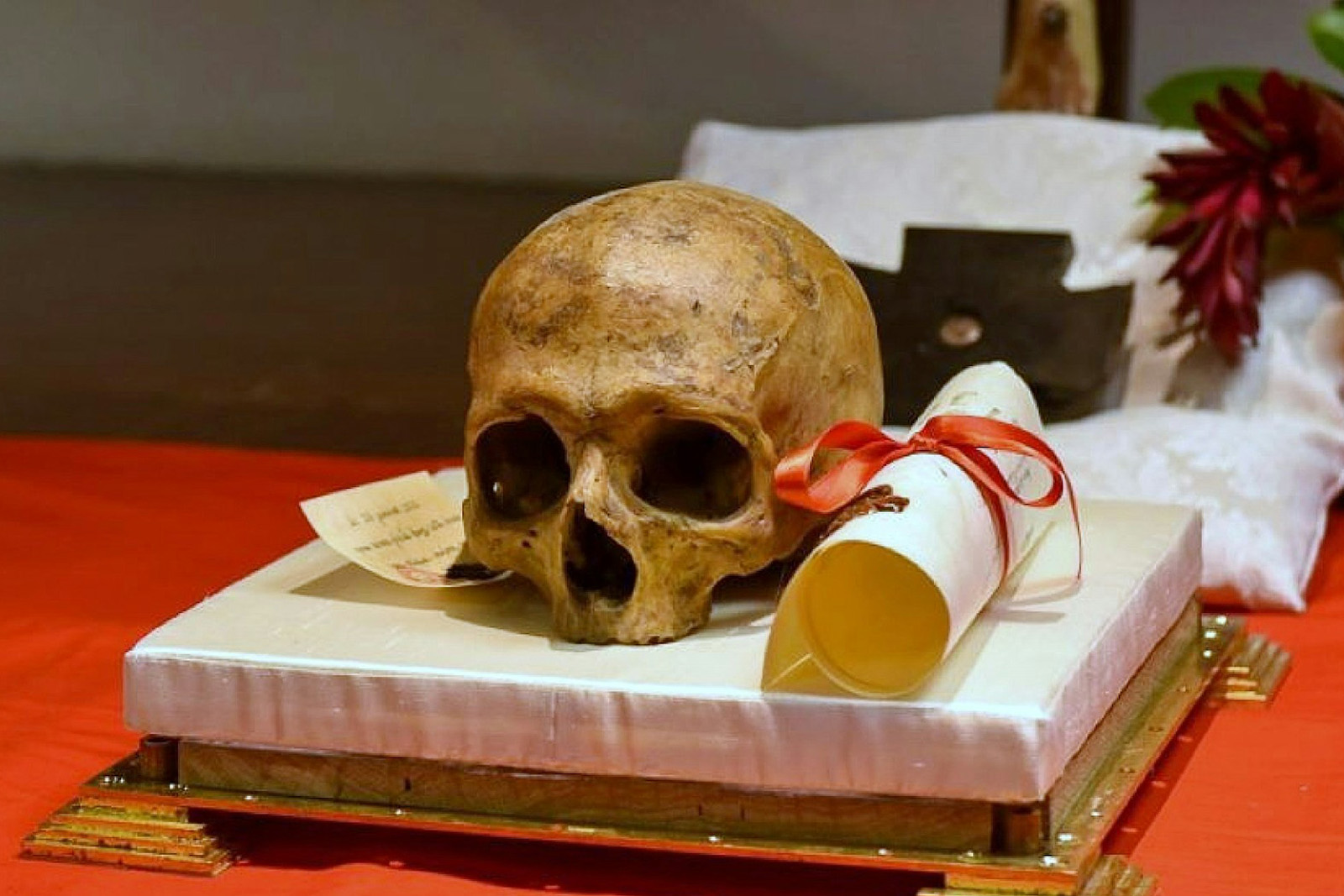

This skull of St. Thomas Aquinas is currently touring parts of the U.S. (Photo courtesy of Thomistic Institute)

Jacqueline Murray

December 5, 2024

(RNS) — The head of the medieval Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas is currently touring 10 U.S. cities in a finale to its yearlong international journey marking the anniversary of the Dominican friar’s birth in Italy 800 years ago, as well as the 750th anniversary of his death and the 700th of his canonization.

Aquinas, the leading exponent of scholasticism, left an indelible mark on the Catholic Church and Western philosophical tradition. Thomistic theology, adapting the ideas of Aristotle to Christian thought, remains the foundation of Catholic teachings and underlies papal pronouncements on matters ranging from social justice to ecumenism. Pope Francis recently commented that Aquinas’ “remarkable openness to every truth accessible to human reason,” could “offer fresh and valid insights to our globalized world.”

With the three coinciding jubilees of a saint of such enduring consequence, Thomas has been celebrated this year in academic conferences and expositions of his relics. Francis, after medieval fashion, has granted a plenary indulgence to those who venerate Thomas by visiting or praying at remnants of his life.

Central to the latter has been his skull, displayed in a new, specially commissioned head reliquary. Since 1369, it has been kept below the altar of the Church of the Jacobins in Toulouse, France, but in January 2023 the original reliquary’s 14th-century seals of authenticity were solemnly broken and the skull was placed in the new case, commissioned by the Dominican order. It was then sent on a yearlong processional route through various European countries, ending now in the United States.

Relics were a significant part of medieval Christianity. It was believed that physical mementos of a saint, such as a piece of clothing or a part of the body, could heal the ill, relieve drought or engineer other miracles. Enough of the right relics — those of national patron saints or avenging saints — could bring victory in battle.

Relics of the most popular saints conveyed tremendous prestige on a church or monastery in the Middle Ages, attracting pilgrims who brought with them the medieval equivalent of tourist dollars. Thus, relics were not only part of a spiritual economy of miracles and devotion but also a secular economy of power, prestige and money. This commodification of relics resulted in a roaring business of buying, selling and even faking relics. Bones and other remains of saints were disassembled to be sent as gifts to friends, political allies and special churches or traded for those of other, higher-status saints.

The relic of St. Thomas Aquinas’ skull is processed at Providence College, Dec. 4, 2024, during a tour stop in Providence, R.I. (Video screen grab)

Saints were even said to collude in this process. The sixth-century Welsh saint Teilo allegedly produced three complete bodies so various groups could claim to have authentic relics. All these activities account for the wide duplication of relics of the same saint in far-flung churches and shrines.

In 1274, Aquinas was summoned by Pope Gregory X to attend the Second Council of Lyon. According to his contemporary biographers, while traveling from his home near Naples, he was struck senseless by a falling branch and later died at the Cistercian abbey at Fossanova. His body apparently remained buried there for some 50 years, but after his canonization, in 1323, the Dominicans claimed it back from the Cistercians. In 1368, the body of this very Dominican saint was translated to Toulouse, where St. Dominic’s Order of Preachers had been founded, and interred in the Church of the Jacobins.

This is where the skull relic remained, safely under the altar, until it was removed last year. But recently, an account of a second skull also belonging to the saint has gained traction. In this telling, a sealed head reliquary containing a skull was discovered in 1585 at the Abbey of Fossanova, accompanied by notarized documents identifying it as the skull of Aquinas. While it has not garnered the same stature that has accrued to the head cherished by the Dominicans of Toulouse, the town of Priverno, near the Abbey of Fossanova, has revered this relic and kept it in a church in town.

The second skull, too, has made a recent public appearance. On March 7, after a Mass celebrated by Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state, the head was taken in procession through the medieval streets of Priverno. The skull was then reportedly driven back to the church in the front seat of a Jeep and returned to its resting place. This event has not occasioned much media attention in Europe or North America, and what few stories there are seem to rely on the same single source published by the Catholic News Service, a subsidiary of EWTN.

This purported skull of St. Thomas Aquinas was processed through the town of Priverno, Italy, on March 7, 2024. (Video screen grab/EWTN)

The existence of two heads for Aquinas is reminiscent of the kind of scholastic question the saint was renowned for resolving. Only one of the heads can be authentic, but which? Did the Cistercians keep the authentic head and send an impostor to Toulouse, along with the authentic body? For its part, the Abbey of Fossanova does not claim to have this relic but rather permits pilgrims to view his empty tomb.

Other questions arise. Is it significant that the friend and secretary who accompanied Aquinas on his last journey and who was with him at Fossanova, Reginald of Piperno (now Priverno), had local roots? Moreover, where are the notarized documents found with the head reliquary in the 16th century? Surely, they would be too important to have been lost in the mists of time. Finally, when was this head removed from Fossanova to the church in Priverno?

RELATED: Why you should get to know Thomas Aquinas, even 800 years after he lived

Perhaps unsurprisingly, scientific and medical researchers want to examine both heads. The Priverno head has already had a preliminary examination by a team of neuroscientists, who are trying to match the physical evidence with a subdural hematoma that would be consistent with the blow to the head Aquinas reportedly suffered. Other scientists are petitioning for permission to perform DNA testing on both heads.

The Roman Catholic Church, meanwhile, seems quite comfortable acknowledging both heads, reflecting the traditional medieval view of the coexistence and plasticity of multiple relics.

(Jacqueline Murray is University Professor Emerita in history at the University of Guelph in Ontario. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

No comments:

Post a Comment