A scene from BonBoné with lead actor Rana Alamuddin. The short film, previously available on Netflix, shows a middle-class Palestinian couple trying to connect even though one of them is in jail. (Groundglass235 + Koussay Hamzeh)

Chandni Desai, Assistant professor, Education, University of Toronto

The Conversation

December 23, 2024

Netflix faces calls for a boycott after it removed its “Palestinian Stories” collection this October. This includes approximately 24 films.

Netflix cited the expiration of three-year licences as the reason for pulling the films from the collection.

Nonetheless, some viewers were outraged and almost 12,000 people signed a CodePink petition calling on Netflix to reinstate the films.

At a time when Palestinians are facing what scholars, United Nations experts and Amnesty International are calling a genocide, Netflix’s move could be seen as a silencing of Palestinian narratives.

The disappearance of these films from Netflix in this moment has deeper implications. The removal of almost all films in this category represents a significant act of cultural erasure and anti-Palestinian racism.

There is a long history of the erasure of Palestine.

Netflix faces calls for a boycott after it removed its “Palestinian Stories” collection this October. This includes approximately 24 films.

Netflix cited the expiration of three-year licences as the reason for pulling the films from the collection.

Nonetheless, some viewers were outraged and almost 12,000 people signed a CodePink petition calling on Netflix to reinstate the films.

At a time when Palestinians are facing what scholars, United Nations experts and Amnesty International are calling a genocide, Netflix’s move could be seen as a silencing of Palestinian narratives.

The disappearance of these films from Netflix in this moment has deeper implications. The removal of almost all films in this category represents a significant act of cultural erasure and anti-Palestinian racism.

There is a long history of the erasure of Palestine.

Cultural erasure

Book cover: ‘The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine’ by Ilan Pappe, professor of history at the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter. (Simon & Schuster)

Since the Nakba of 1948, Zionist militias have systematically ethnically cleansed Palestinians and destroyed hundreds of cities, towns and villages, while also targeting Palestinian culture.

Palestinian visual archives and books were looted, stolen and hidden away in Israeli-controlled state archives, classified and often kept under restricted access. This targeting of visual culture is not incidental. It is a calculated act of cultural erasure aimed at severing the connection between a people, their land and history.

Another notable instance of cultural erasure includes the thefts of the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) visual archives and cinematic materials. In 1982, the PLO Arts and Culture Section, Research Centre and other PLO offices were looted during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The Palestinian Cinema Institutions film archives were moved during the invasion and later disappeared. Theft and looting also occured during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s and recurrent bombardments of Gaza.

This plundering of Palestinian cultural institutions, archives and libraries resulted in the loss of invaluable cultural materials, including visual archives.

To maintain Zionist colonial mythologies about the establishment of Israel, the state systematically stole, destroyed and holds captive Palestinian films and other historical and cultural materials.

Since the Nakba of 1948, Zionist militias have systematically ethnically cleansed Palestinians and destroyed hundreds of cities, towns and villages, while also targeting Palestinian culture.

Palestinian visual archives and books were looted, stolen and hidden away in Israeli-controlled state archives, classified and often kept under restricted access. This targeting of visual culture is not incidental. It is a calculated act of cultural erasure aimed at severing the connection between a people, their land and history.

Another notable instance of cultural erasure includes the thefts of the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) visual archives and cinematic materials. In 1982, the PLO Arts and Culture Section, Research Centre and other PLO offices were looted during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The Palestinian Cinema Institutions film archives were moved during the invasion and later disappeared. Theft and looting also occured during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s and recurrent bombardments of Gaza.

This plundering of Palestinian cultural institutions, archives and libraries resulted in the loss of invaluable cultural materials, including visual archives.

To maintain Zionist colonial mythologies about the establishment of Israel, the state systematically stole, destroyed and holds captive Palestinian films and other historical and cultural materials.

Palestinian liberation cinema

By the mid-20th century, Palestinian cinema emerged as a vital component of global Third Worldism, a unifying global ideology and philosophy of anticolonial solidarity and liberation.

Palestinian cinema aligned with revolutionary filmmakers and cinema groups in Asia, Africa and Latin America, all seeking to reclaim their histories, culture and identity in the face of imperial domination.

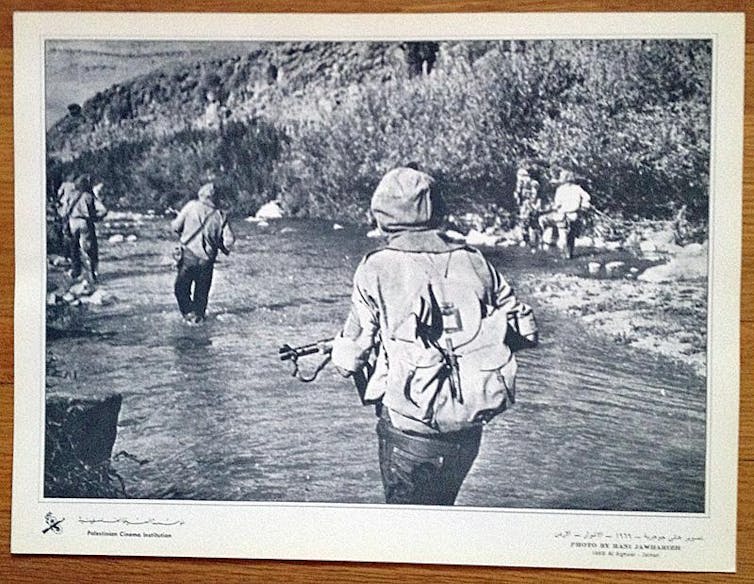

This photo is taken by Hani Jawharieh, a Palestinian filmmaker who was killed in 1976 while filming in the Aintoura Mountains of Lebanon. CC BY

The PLO’s revolutionary films of the 1960s and 1970s were driven by the national liberation struggle and the desire to document the Palestinian revolution. Created as part of a broader campaign against colonialism and imperialism, PLO filmmakers aimed to rally international solidarity for the Palestinian cause through Afro-Asian, Tricontinental and socialist cultural networks.

The PLO’s revolutionary films of the 1960s and 1970s were driven by the national liberation struggle and the desire to document the Palestinian revolution. Created as part of a broader campaign against colonialism and imperialism, PLO filmmakers aimed to rally international solidarity for the Palestinian cause through Afro-Asian, Tricontinental and socialist cultural networks.

Censorship

Censorship became one of the primary mechanisms for repressing cultural production in the Third World. Colonial and imperial powers, as well as allied governments, banned films, books, periodicals, newspapers and art that conveyed anti-colonial and anti-imperialist sentiments. Their films and cultural works were denied distribution in western and local markets.

Settler colonial states such as Israel rely on the destruction and suppression of the colonized narratives to erase historical and cultural connections to land. By doing so, they undermine Indigenous Palestinian claims to sovereignty and self-determination.

Many Palestinian cultural workers including writers, poets and filmmakers were persecuted, imprisoned, exiled, assassinated and killed.

In an essay about the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the Sabra and Shatila massacres, the late Palestinian American literature professor, Edward Said, explained how the West systematically denies Palestinians the agency to tell their own stories. He said the West’s biased coverage and suppression of Palestinian narratives distorts the region’s history and justifies Israeli aggression. For a more truthful understanding of history, Palestinians needed the right “to narrate,” he said.

Resistance

Despite the denial to narrate, generations of Palestinian filmmakers, including Elia Suleiman, Michel Khleifi, Mai Masri, Annemarie Jacir and many others, have contributed to and evolved this cinematic tradition of resistance.

Their films centre the lived experiences of Palestinians under settler colonialism, occupation, apartheid and exile.

By capturing the Palestinian struggle, freedom dreams, joy, hopes and humour, they help to humanize a population.

Despite the denial to narrate, generations of Palestinian filmmakers, including Elia Suleiman, Michel Khleifi, Mai Masri, Annemarie Jacir and many others, have contributed to and evolved this cinematic tradition of resistance.

Their films centre the lived experiences of Palestinians under settler colonialism, occupation, apartheid and exile.

By capturing the Palestinian struggle, freedom dreams, joy, hopes and humour, they help to humanize a population.

A scene from TIFF selection, Farha, about a girl trying to pursue her education in 1948 Palestine just before the Nakba.

After Netflix first launched the Palestinian Stories collection in 2021, the company was criticized by the Zionist organization, Im Tirtzu. They pressured Netflix to purge Palestinian films.

A year later, Netflix faced more pushback — this time from Israeli officials — when it released Farha, a film set against the backdrop of the 1948 Nakba. Israeli Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman even took steps to revoke state funding from theatres that screened the film.

The Israeli television series Fauda, produced by former IDF soldiers Lior Raz and Avi Issacharoff, remains on the platform. Fauda portrays an undercover Israeli military unit operating in the West Bank. The series has faced significant criticism for perpetuating racist stereotypes, glorifying Israeli military actions, and whitewashing the Israeli occupation and systemic oppression of Palestinians.

Such media helps to legitimize and normalize violent actions committed against Palestinians.

After Netflix first launched the Palestinian Stories collection in 2021, the company was criticized by the Zionist organization, Im Tirtzu. They pressured Netflix to purge Palestinian films.

A year later, Netflix faced more pushback — this time from Israeli officials — when it released Farha, a film set against the backdrop of the 1948 Nakba. Israeli Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman even took steps to revoke state funding from theatres that screened the film.

The Israeli television series Fauda, produced by former IDF soldiers Lior Raz and Avi Issacharoff, remains on the platform. Fauda portrays an undercover Israeli military unit operating in the West Bank. The series has faced significant criticism for perpetuating racist stereotypes, glorifying Israeli military actions, and whitewashing the Israeli occupation and systemic oppression of Palestinians.

Such media helps to legitimize and normalize violent actions committed against Palestinians.

Suppression in the time of genocide

In a time of genocide, Palestinian stories, films, cultural production, media and visual culture transcend being mere cultural artifacts. They are tools of defiance, sumud (steadfastness), historical memory, documentation and preservation against erasure. They assert the fundamental right to Palestinian liberation and the right to narrate and exist even while being annihilated.

As such, in the past 400+ days, Israel has intensified its systematic silencing and erasure of Palestinian narratives.

One hundred thirty-seven journalists and media workers have been killed across the occupied Palestinian Territories and Lebanon since Israel declared war on Hamas following its Al-Aqsa Flood Operation on Oct. 7, 2023. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, there are almost no professional journalists left in northern Gaza to document Israel’s ethnic cleansing. It has been the deadliest period for journalists in the world since CPJ began collecting data in 1992.

Israel has also targeted, detained, tortured, raped and killed academics, students, health-care workers and cultural workers; many who have shared eyewitness accounts and narrated their stories of genocide on social media platforms.

Israel has censored and silenced Palestinian narratives through media manipulation, digital censorship and the destruction of journalistic infrastructure. Palestinian cultural and academic institutions, cultural heritage and archives have also been bombed and destroyed in Gaza, termed scholasticide. The aim of this destruction is to obliterate historical memory, and suppress documentation of atrocities.

The genocide and scholasticide will prevent the Palestinian people’s ability to fully preserve centuries of history, knowledge, culture and archives.

Netflix’s decision to remove the Palestinian Stories collection and not renew the licences of the films during this time makes it complicit in the erasure of Palestinian culture.

Chandni Desai, Assistant professor, Education, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment