We can’t talk about productivity without talking about distribution

D.T. Cochrane / December 19, 2024 /

_(I0058208)_800_640_90.jpg)

Economists like to fashion themselves as the “adults in the room.” However, their notion that incomes are determined by productivity is incredibly naïve, writes D.T. Cochrane. Photo courtesy Archives of Ontario/Wikimedia Commons.

Earlier this month, Statistics Canada released the latest numbers on productivity. Economists are in a tizzy over a third consecutive quarter of falling productivity, which means we’re getting less output per unit of input. There is plenty of misplaced blame being cast at predictable targets like government spending and regulation.

Desjardins, North America’s largest federation of credit unions, offered a particularly bad take on Canada’s productivity. In its analysis of the latest numbers, the financial institution set its sights squarely on workers. But in doing so, it created a misleading picture of the issue.

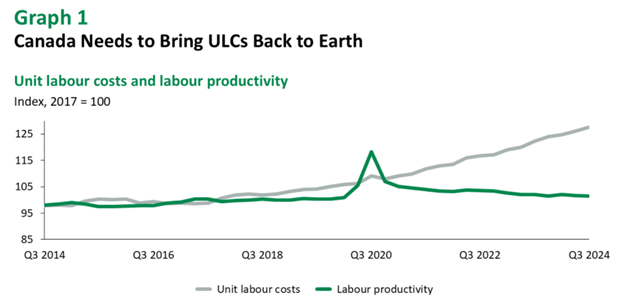

The analysis includes this chart:

The chart compares labour productivity with unit labour costs. While labour productivity is the economic output per hour of paid work, unit labour costs are the hourly compensation of workers per unit of output. Whenever productivity increases, the economy generates more per hour. Both series are indexed to equal 100 in 2017.

The chart creates the impression that workers are taking far more than their fair share of the economic pie as productivity plateaus. Despite having over $400 billion in assets under management, Desjardins apparently does not know the difference between nominal and price-adjusted values, which are typically referred to as “real.”

Output for both series is “real” GDP. That means the labour productivity measure removes the impact of inflation. However, workers’ compensation is not adjusted for prices. It is reported in current dollars, also known as nominal values. It doesn’t tell us the actual purchasing power of the workers receiving the compensation.

By using the data this way, Desjardins is trying to revive the notion that greedy workers are to blame for inflation—or will be to blame if inflation returns; this is the dreaded wage-price spiral. The Bank of Canada invoked this same spectre as inflation was picking up despite consumer prices rising before wages and the clear evidence of corporate profiteering in the preceding quarters.

The recent increase in unit labour costs is the result of workers trying to regain their lost purchasing power. But have they gone too far? Are workers actually taking more than their fair share?

Labour’s share of output

A better measure to answer this question would be the labour share, which is labour compensation divided by GDP, both in current dollars. That is comparing apples to apples.

And instead of starting in 2014, let’s look at all the data available, which goes back to 1961.

Rather than the misleading picture of runaway wages presented by Desjardins, we see that the share of GDP going to workers has not even returned to its long-term average. We can also see that the share going to workers from the late-1960s until the mid-1990s was markedly higher than it has been over the last three decades.

The slowdown of productivity growth is a problem. However, the focus on productivity turns our attention away from the more serious problem of distribution.

It’s the distribution, stupid

“Who gets what? Why and how do they get it? What should they get?”

These questions express long-standing moral and ethical dilemmas at the core of social organization. They lack objective answers. That is, unless you live in the mythical world of orthodox economic theory.

In the world of orthodox economists, competitive markets balance supply and demand among selfish individuals, and allocate income according to productivity. In such a world, distribution is objective and not a matter for ethical debate. According to orthodox theory, the CEO with an income of $10 million is 200 times more productive than a personal support worker (PSW) earning $50,000. In the economists’ world, even though the CEO may spend their days lobbying to eliminate health and safety regulations while the PSW spends their days caring for our elders, the ethics of the situation cannot be questioned because “The Market” has spoken.

Research from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives shows that average CEO pay has increased from about 170 times that of the average worker in the late-2000s and early-2010s, to almost 250 times in 2023. Economists want us to believe that these CEOs are simply more productive and therefore deserve their obscene pay.

But, we do not live in the economists’ fantasy world. In our actual world, there is a very real struggle over distribution. And that struggle is behind many of our current social woes. Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign pithily declared what that election was about: “It’s the economy, stupid.” Distribution is an indelible aspect of the economy, with consequences for every other aspect of people’s lives.

Increased productivity is undeniably a good thing. However, it is not that meaningful for people if they aren’t actually getting a fair share. For better or worse, we are relative beings. If I get $1 while someone else gets $100, I do not necessarily feel better off. That is especially true if I got $1 for working and they got $100 for owning lucrative assets.

An increase in aggregate productivity does not tell us who is benefitting from growth or who might be paying the costs.

Who has benefitted from higher productivity?

The Bank of Canada warns that unless productivity increases, rising wages will bring higher inflation. But why is it only now that they insist wages and productivity be linked? Where were they for the past 40 years as productivity climbed while most workers’ purchasing power stagnated? We were producing more. But once we adjust for inflation, most of us weren’t actually receiving more.

This chart is the average market income, adjusted for inflation, of each income group, from the 10 percent of families with the lowest incomes to the 10 percent with the highest incomes.

For the bottom 70 percent, the purchasing power of their market incomes was lower in 2000 than it was in 1980. For the bottom 50 percent, it was still lower in 2022. Meanwhile, the top 10 percent received $54,600 more in 2000 than in 1980. As of 2022, the top decile had gained an additional $66,800.

According to orthodox economists, this means the top 10 percent of families became much more productive while the bottom 50 percent had not increased their productivity at all. However, there is no actual evidence to support the claim that income is distributed according to productivity. It is merely asserted.

Although productivity growth has slowed, it has largely continued to trend upward. But as long as it lags behind the growth of the top incomes, unequal distribution of gains will worsen.

Maldistribution of the social product is part of the growing and widespread sense of insecurity and resentment. Millennials who cannot afford a home are understandably resentful of the wealthy who collect rent by owning multiple houses. People working precarious jobs are understandably resentful of those who can live off idle returns from large asset portfolios. It feels egregiously unfair.

“Life isn’t fair.” What child has not been met with this response when they have called out an injustice? It is true that life is not fair. But that does not mean we should stop trying to make it more fair. Improved distribution of the social product is a necessary step toward fairness. But not only would fairer distribution reduce feelings of social alienation, there is strong evidence that it would also improve productivity.

Economists like to fashion themselves as the “adults in the room.” However, their notion that incomes are determined by productivity is incredibly naïve. It completely ignores the role of power in the actual determination of distribution. The guise of objectivity that orthodox economists give to distribution diverts us from the difficult adult conversation that we must have: who should get what and why?

D.T. Cochrane is senior economist with the Canadian Labour Congress, Canada’s largest labour organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment