Top of the Mormon

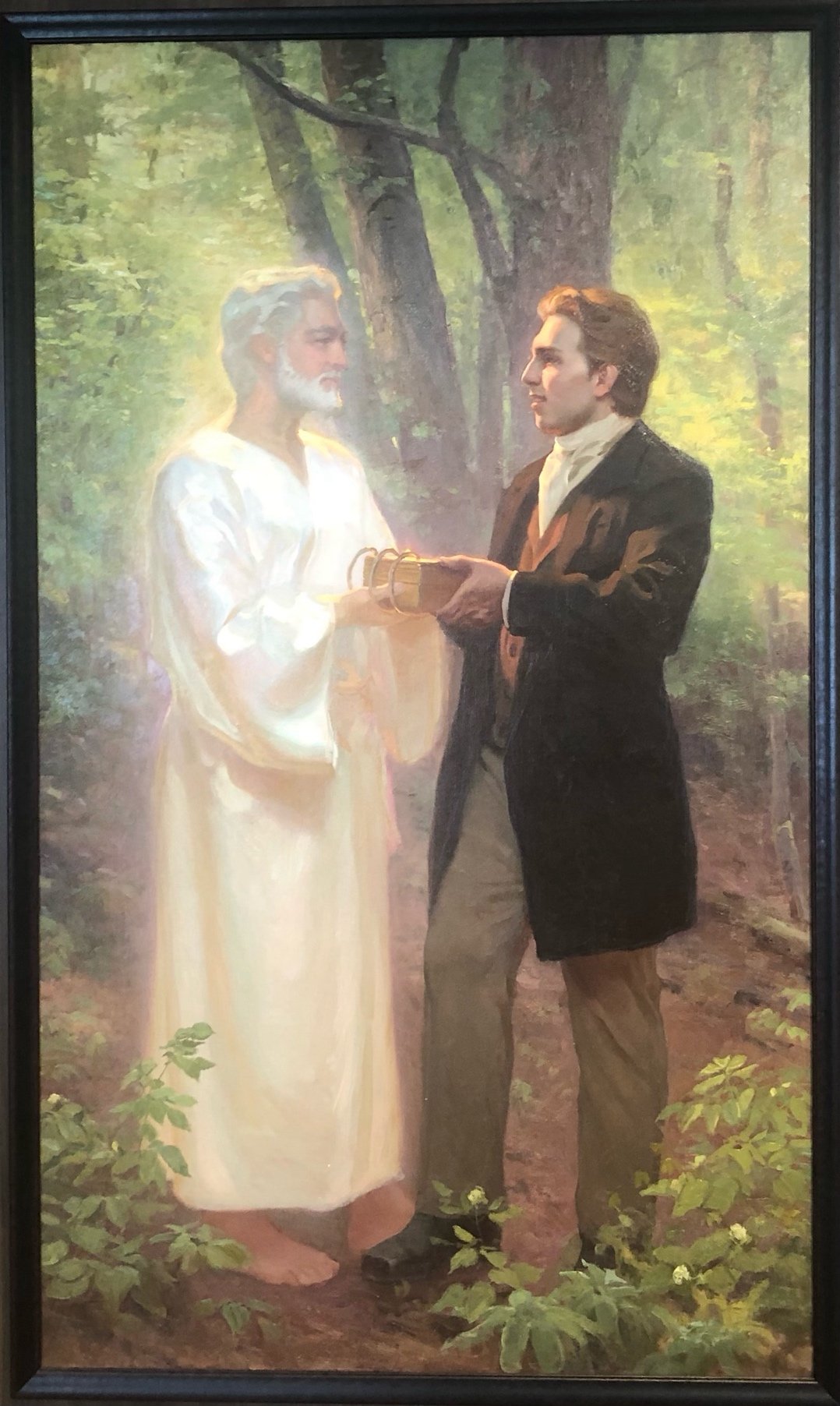

Returning the Gold Plates to Moroni (1829), Linda Curley Christensen and Michael Malm, 2020.

Sacred Grove Welcome Center, Palmyra, New York,

Over my thirty years living in Upstate New York, I’ve raced past the Thruway exit for Palmyra dozens of times while driving the ninety miles from Ithaca to Rochester. Usually, I’ve been rushing to play a concert, or to listen to one, at the Eastman School of Music. But there have been plenty of times when I’ve been on my way to or from Rochester that have involved far less-pressing engagements.

These more relaxed journeys could easily have allowed me time to make an excursion to Mormonism’s Sacred Grove in Palmyra twenty-five miles west of Rochester. Even easier to reach is the Whitmer Farm where the Church of Latter-day Saints was founded in April of 1830. It is half-an-hour from Palmyra to the farm, which is just 40 miles northwest of Ithaca.

My grandfather was baptized in a creek in the Mormon town of Menan, Idaho in 1905. He was the great-grandson of David Dutton Yearsley, a wealthy Quaker merchant who was baptized by Joseph Smith in 1841. My forbear became a close friend of Smith’s and loaned him large sums of money—never repaid. Yearsley also financially backed Smith’s 1844 presidential bid. Smith was killed—martyred, in Mormon discourse—by a mob in Carthage, Illinois in the summer of that year, five months before the election. Yearsley continued west and died near Council Bluffs, Nebraska in 1849.

No one on our stout branch of the spreading Yearsley family tree has been Mormon for a century now. A baptized and confirmed Lutheran, if non-practicing since his teenage years, my father had nonetheless wanted to name me David Dutton Yearsley. That would have made me the third person with that name over six generations. My mother refused.

All this probably has something to do with my fantastical fear that, if I visited Palmyra, commando LDS genealogists might kidnap me into the church or at least force me to explain my Mormon connections. Worse, I might even be visited by Moroni in the Sacred Grove, which, according to Wikipedia (citing the Patheos multi-faith religion project), is the 74th “Most Holy Place on Earth.”

Unlike me, my daughters are native New Yorkers. The younger of the two, Cecilia, has long been fascinated by the region’s history, including the religious revivalism that spread across the so-called Burned-over District of central and western New York in the first half of the nineteenth century. It was in the course of this Second Great Awakening that Mormonism was born and from whence it proceeded to become one of the most dynamic and successful religious movements of the last two centuries. Cecilia is also a well-informed critic of the dubious sustainability schemes of present day to decarbonize the Burned-over District. During the pandemic, which coincided with her college years, Cecilia was home with us in Ithaca for a couple of long stretches. She had wanted to visit the Sacred Grove then, but it was closed. She now lives in London and returned this year for the holidays.

She ascertained that the Sacred Grove was open again, so the Sunday before Christmas we climbed into the white Subaru spattered with mud and headed to Palmyra.

It had gotten cold after a long fall and early winter of scarily warm weather. That Sunday it was 10F. The windshield wiper fluid nozzle had frozen, but through the salt-caked glass we could still see far across the snowy fields, past the leaning barns and rusty silos and the stands of leafless trees. After twenty minutes, New York’s largest landfill, Seneca Meadows, rose up at the north end of Lake Cayuga. The 350-foot-high snowcapped summit of trash could almost stand in for a cluster of western peaks spied and crossed by the Mormon trekkers of yore. Go West old man, but only as far as Palmyra!

There was much more snow north of the Thruway due to the increased precipitation coming off of Lake Ontario—“pioneer weather” the sexagenarian docent, a missionary from Boise coming to the close of a year-and-a-half stint at the Sacred Grove, would later call it as we traipsed across the snowy fields of the Smith Farm.

We still had a few minutes before the Sacred Grove opened at 1pm, so we pulled in first to the Temple, the first one in New York State. This classic example of Mormon architecture seems to share basic aesthetic principles with Fascist buildings, except that its boxy, concrete elements are crowned by a gilded statue of the trumpet-blowing angel Moroni. Dedicated in 2000, the bunker-like structure sits above the valley where the Smith Farm and Visitors Center lie. The site is a mile south of the village of Palmyra on the Erie Canal.

An SUV with Virginia plates had just pulled up in front of us and a family of six piled out. When Cecilia and I walked by the vehicle, we realized that they had left it running as they took their time talking around the temple. I thought of George Hayduke from Edward Abbey’s rollicking eco-terrorist novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang—the scene where Hayduke hops into an idling police car and wreaks some fabulous havoc. Hayduke’s nemesis is the nefarious Mormon, Bishop Love.

Across the flats from the Temple, on the next the wooded ridge is the Sacred Grove. It was here in 1820 that the teenage Joseph Smith saw a pillar of light and was visited by two figures, God the Father and God the Son, who told him that all then-existing churches in their various denominations were false and corrupt.

Later that afternoon, the Virginia family’s oldest boy was asked play the part of Joseph himself at the age, even made to hold up a replica of the plates hidden in a burlap sack.

The paintings in the one-room welcome center depict crucial moments of Mormon revelation: the godly visitation of in the Scared Grove, Jesus and his Father looking like identical twins. It’s a weirdly provocative theological image from this non-trinitarian sect. Another picture shows Moroni coming to the young Joseph in the attic of the family’s cabin. Canned Christmas carols emanate from hidden speakers, their saccharine glow artfully matching the painting’s pastel colorings.

I’ve tried to read the Book of Mormon but could never make much headway through its hokey biblicalisms and technical jargon—Urim, Thummim, Cimiter. Our docent throws around many of such terms and everyone appears to know exactly what they mean. There seems to be no inkling that any among us are non-Mormonism. Except for our ragged, vaguely Gorp Corps vestments, Cecilia and I definitely look the part with our above-average stature, good teeth and blond hair. Still, the learning curve is steep. We nod when the others easily answer questions like those about the weight of the plates and the hiding of them in the bag of beans when gold-hungry thugs stormed into the newer frame house built by the Smiths later in the 1820s and still largely intact.

Aside from elucidating Mormon doctrine, our guide identifies fox, deer and rabbit tracks for the young urbanites. These Western Missionaries come East cling to their connection to the agrarian past. The Mormon Church has been buying up large tracts of land in Palmyra since 1907 and even moved the state route off their property to return the ensemble of historic buildings to its rural setting. Say what you will about the preposterous revelations retailed by Smith, his followers have, with the exception of the menacing hilltop Temple, carefully preserved the natural beauty of the hills and valleys around the Sacred Grove.

After the tour, we drive down Main Street in Palmyra past the Protestant Churches. They look badly neglected, especially when compared with the spotless indestructibility of the Mormon Temple we’ve just come from.

The sun sets through the Sacred Grove.

Harried by the authorities, Joseph Smith repaired first to Harmony, Pennsylvania on the banks of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania before returning to Upstate New York and the Whitmer Farm, where he officially founded the Church of Latter-day Saints in 1830. We arrive at the farm just after sunset at 4:30, a half-hour before closing time.

Inside this Welcome Center, Sister Hope is thrilled to see us. She is in her fifties, also on a mission away from her farm in Eastern Washington. She takes us to another reconstructed cabin, this one where the Book of Mormon was written down, the barely literate Smith making use of scribes to produce the text. When Sister Hope asks us to imagine what it was like to hear the prophet dictating in the room above, tears well up in her eyes.

A new husband-and-wife team of missionaries has just arrived from Utah. They are in training for this latest posting and join our little tour in order to hear again Sister Hope’s ardent and richly informative descriptions of the church’s early history and these events’ enduring significance. After the tour of the cabin, she ushers us into a small screening room in the Welcome Center so that we can watch a four-minute film that “can only be seen here.”

The movie brings us back to the cabin in 1830, then on the trek to Utah. There are baptisms in creeks and displays of incredible toughness as pioneers in wagons brace themselves against the bitter Plains winds. Salt Lake City and the Tabernacle grow and grow across the decades.

Our day of LDS history begins and ends with music. The film’s soundtrack is provided by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and pursues an inexorable crescendo as thousands across the Pacific fill the new Temples of Polynesia and Southeast Asia. Moroni is hoisted by a crane atop a tower over the African rainforest.

After the movie, Sister Hope asks us what our connection to the Church is. Cecilia tells her that we are descendants of David Dutton Yearsley. Sister Hope is thrilled and says that during her time on the track team at BYU-Idaho, she was helped by the trainer, Nate Yearsley. “I’m sure he’s a relative,” I mumble. Before we leave, Sister Hopes reminds us that tomorrow is Joseph Smith’s birthday. We thank her for her tour and make our escape. The vast parking lot is empty except for a lone Subaru.

No comments:

Post a Comment