Finding Zero

The emissions reduction circus continues.

(Article originally published in Jan/Feb 2025 edition.)

The global maritime industry is racing to cut emissions with solutions ranging from cutting-edge tech to, well… sails. Yes, we've come full circle. The same technology that powered pirates is now hailed as the future of sustainable shipping. What a time to be alive!

While we await warp drives and fusion reactors, the industry juggles alternative fuels – methanol, ammonia, hydrogen – plus hybrid propulsion, carbon capture and electrification. Regulations tighten the noose: IMO 2023 introduced energy efficiency rules; the EU ETS expanded to maritime in 2024, tripling compliance costs by 2030, and FuelEU Maritime kicked in this year with strict emissions targets.

The IMO's 2023 GHG Strategy aims for net-zero by 2050 with milestones along the way: 20 percent reduction by 2030 and 70 percent by 2040. Mid-term measures are due by 2027, following key meetings this year.

The race is on – powered by wind, data and just a dash of regulatory panic.

"GO GREEN, SAVE SOME GREEN"

The Liberian Registry (LISCR), the world's largest ship registry by gross tonnage, is deeply embedded in the maritime industry's efforts to meet decarbonization targets. Thomas Klenum, Executive Vice President of Innovation & Regulatory Affairs, sheds light on how the registry adapts to the decarbonization challenge.

"Our goal is to accelerate the transition to net-zero by 2050, embrace innovation and apply new IMO regulatory frameworks," he says, referencing the launch of LISCR's Innovation and Energy Transition Team in 2024. The team collaborates directly with shipowners, shipyards and design firms, ensuring sustainability is embedded from the design phase onward.

A key part of LISCR's strategy is its incentive programs.

"We offer discounts on registration fees for ships enrolled in green programs," Klenum states. The registry actively enhances these schemes to align with the evolving regulatory landscape, including EEXI and CII requirements. The message is clear: "Go green, save some green."

While alternative fuels dominate the discourse, Klenum quickly points out that efficiency gains are just as critical. "Wind-assisted propulsion systems are showing promising results," he notes, with LISCR soon to release an entire year's worth of data from Liberian-flagged vessels employing these systems.

Hull optimization also remains a priority. "With zero or near-zero emission fuels expected to be expensive and limited, efficiency becomes a survival strategy," Klenum emphasizes. Optimizing hull forms can significantly reduce both fuel consumption and operational costs.

When it comes to onboard carbon capture, LISCR is pushing the boundaries. "We've submitted proposals to the IMO to recognize carbon capture as a legitimate decarbonization technology," Klenum reveals, stressing the need for regulatory frameworks to catch up so shipowners can receive proper credit for captured emissions.

The revised 2023 IMO GHG Strategy adds another layer of complexity by expanding from tank-to-wake to well-to-wake emissions. "Depending on how the fuel is produced and transported, you could even bunker fuel with a negative CO2 impact," Klenum says, noting the potential for new net-zero pathways.

LISCR is also exploring emerging technologies. "We're conducting trials with artificial intelligence and autonomous shipping (with Avikus)," Klenum states. These technologies offer efficiency gains in route optimization, machinery operations and even collision avoidance, contributing to both decarbonization and navigational safety.

Klenum provides a candid assessment of nuclear power: "We've been involved in nuclear power plants for fixed locations, which is simpler due to localized regulatory frameworks. However, trading with nuclear-powered vessels globally faces complex challenges. The IMO's nuclear ship code is outdated, though discussions are underway to update it."

Despite the hurdles, he sees potential: "In the long term, nuclear could play an important role. A nuclear-powered vessel (which may not need refueling over its lifecycle) might offer a more stable, low-emissions solution compared to the cumulative risks of handling toxic alternative fuels like ammonia over 25 years."

He also voices concerns over regional emissions regulations: "We're not in favor of fragmented regional requirements for international shipping. Global regulations should come from the IMO to maintain consistency and fairness."

Regarding the timeline for the IMO's mid-term measures, Klenum was cautiously optimistic: "It could be achieved, but it requires global collaboration, technological innovation and scaling up near-zero carbon fuel availability." The roadmap includes the MEPC 83 meeting in April with critical decisions expected on fuel intensity standards and carbon pricing mechanisms. "We're up against a tight deadline," he admits, with implementation slated for early 2027.

Klenum concludes that decarbonizing shipping isn't about a single solution: "The biggest challenge is balancing innovation, new technologies and alternative fuels. It's not as simple as discovering a zero-emission fuel."

FUEL FUTURES FOG

In maritime decarbonization, Finland-based Auramarine is the go-to specialist for fuel supply systems across methanol, ammonia and biofuels. But beyond the polished technical specs, there's a landscape riddled with practical challenges that even the most sophisticated systems can't mask.

Methanol is often pitched as a "drop-in" fuel, but as Auramarine's responses make clear, it's more of a "rip out and rebuild" situation. Its systems demand dedicated safety automation, leak detection and specialized handling – hardly the seamless transition some in the industry like to suggest.

Auramarine CEO John Bergman says, "Quality is key as shipping navigates a multifuel future." Translation: Swapping fuels is easy; making it work safely isn't. Plus, methanol comes with a hidden caveat: Its lower energy density means vessels need up to twice the volume compared to traditional fuels to achieve the same range – a detail often missing from the marketing brochures.

Ammonia offers zero-carbon potential, but toxicity levels make LNG look like a scented candle. Auramarine's Ammonia Release Mitigation System (ARMS) sounds impressive on paper, focusing on gas capture, leak prevention and zero emissions to both air and water. Yet, behind the jargon, it boils down to one thing: mitigating risks that could make a minor leak catastrophic.

Risk thresholds for ammonia exposure are measured in parts per million (ppm), leaving no margin for error in operational settings. Bergman acknowledges this tightrope act, noting, "In navigating the energy transition's unknowns, experience and collaboration matter." Experience, yes—but even experience doesn't entirely solve ammonia's operational headaches.

Any volunteers for the first engine room crew? Ya, me neither.

When it comes to biofuels, Auramarine shifts from pioneering to pragmatic. Its Porla Fuel Measurement System is designed to ensure fuel stability, but the broader issue remains: Biofuels may work technically, but scaling them sustainably is another matter entirely. While biofuels can claim up to an 80 percent reduction in lifecycle CO2 emissions, feedstock availability is the elephant in the engine room. Without sustainable sourcing at scale, the emissions savings look good on paper but falter in practice.

Regulatory pressure is accelerating these transitions, particularly from the IMO 2023 GHG Strategy and the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). But even as regulations tighten, the real issue isn't whether Auramarine can build systems for these fuels – it seems they can. The question is whether the fuels themselves are ready for prime time.

Bergman's closing sentiment, "If we want a healthy planet for our children, we need to start now," feels right. But the industry still seems to be debating where "now" even begins.

EMISSIONS DATA SMOG

While fuel suppliers tackle decarbonization from the engine room, Houston-based Cyanergy works from the data deck. Its focus? Continuous emissions monitoring systems (CEMS) that promise not just compliance but clarity.

In an industry where emissions reporting often relies on manual fuel logs and conversion formulas (like the EPA's "1 gallon of diesel = 22.8 lbs. of CO2"), Cyanergy's approach is refreshingly direct: Measure what you emit, not what you estimate.

"Estimates leave room for inaccuracies, which can result in misleading reports, unattainable targets and even regulatory fees," says CTO Mohammed Khambaty. Enter continuous monitoring, where real-time data reduces anomalies, identifies inefficiencies and minimizes carbon accounting errors. Translation: less guesswork, fewer surprises.

Cyanergy estimates that over 90 percent of ships still rely on manual emission calculations, exposing operators to the risks of inaccurate reporting and potential penalties. Its IoT-enabled system, utilizing LoRaWAN (a low-power, wide-area networking protocol), integrates seamlessly with onboard sensors, including physically installed CO2 sensors in the engine and exhausts.

"Direct measurements have shown a three percent discrepancy compared to EPA/MARPOL formulas," Khambaty notes, "translating to significant cost savings for large vessels."

Steve Manz, CFO of Cyanergy, emphasizes the financial impact: "The carbon market is around $70–75 per metric ton for CO2. A big ship emits about 250 tons of CO2 per day at sea. Those are big numbers. The financial risk is huge if you're underestimating – or worse, overpaying."

Cyanergy claims its technology can save large vessels around $150,000 annually. Based on Shelf Drilling data, they've reported four to seven percent fuel savings with an ROI projected within one year. Manz adds, "These savings don't even factor in reductions in administrative and labor costs tied to compliance."

Looking ahead, Cyanergy is exploring blockchain for immutable, transparent carbon credit tracking and machine-learning to enhance predictive capabilities. It anticipates a standardized emissions monitoring scheme within five to six years.

FINDING ZERO

And so the maritime industry sails on, powered by wind, data and a fair amount of regulatory paperwork. What a time to be alive!

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

A Radical Solution to the Challenges of Slow Steaming

Slowing down vessels may be the most direct way to cut fuel consumption and emissions, but it is not without its issues. A new solution from Wärtsilä, Fit4Power, offers an alternative that tackles many of the challenges of running large engines on low load, while monitoring since the first installations in October 2022 reveals just how effective radical derating can be. Andreas Wiesmann, General Manager of Strategy and Business Development for 2-stroke Engine Services at Wärtsilä Marine, explores the potential of the technology, leveraging broad industry expertise to demonstrate its transformative effect on the shipping industry.

Slow steaming is a crucial component of emissions reduction strategies for vessels that do not need speed to cater to their markets, such as those on scheduled routes as opposed to spot trades. One of the key drivers is IMO’s Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), which demands annual improvements in operational efficiency from vessels based on reported fuel consumption and voyage data. Wärtsilä analysis shows that, without modifications or operational measures, more than 80% of the global merchant fleet could fall into the ‘D’ and ‘E’ CII ratings by 2030, requiring mandatory corrective action.

Balancing speed and emissions

Slowing vessel speed therefore offers a straightforward option for cutting fuel and emissions without investing in new efficiency technologies. However, operating at low loads well below those for which they were designed is not an ideal scenario for engines. As a result, an overall reduction in fuel consumption and emissions can carry a significant penalty in efficiency. Less fuel is used overall, but more fuel is needed to generate an equivalent power output.

The practice leaves operators with another cost problem: the maintenance requirements of a big engine with the power output of a small engine. In addition, because engines that run outside their optimal load are more prone to wear, those costs can also increase with slow steaming. The result is an oversized engine for which operators are paying oversized maintenance and fuel bills, without being able to take advantage of the surplus installed power.

Further, slow steaming does not necessarily help comply with design efficiency regulations. The IMO’s Energy Efficiency Index for Existing Ships (EEXI), for example, does not directly demand that less fuel is used but instead that available power is limited. That means using mechanical or software-based measures to ensure that the lower power is maintained (with an exception for emergencies). Those limitation solutions come at a cost and add complexity to the engine configuration.

A radical approach

When Wärtsilä applied itself to the inherent problems of slow steaming, it came up with a radical solution. If vessel operators can sail at slower speeds, the most efficient way to do it would be to reduce the size of the engine. Thermodynamically, running a smaller engine at higher loads will always be more efficient than running a bigger engine at low loads due to relatively lower mechanical losses and a more optimal air-fuel mix in the combustion chamber.

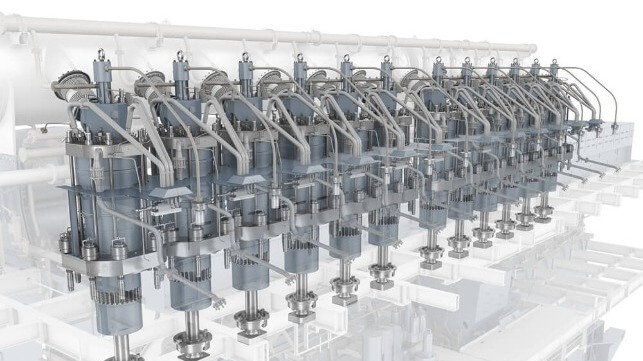

While this principle has guided engine selection for newbuild vessels for decades, until recently it had little value for ship operators with existing vessels. It was not viable to reduce the size of an engine already installed. The unique proposition behind Wärtsilä’s radical derating solution for two-stroke engines is that it makes reducing the size of the engine achievable.

The advanced retrofit solution enables ship owners to reduce the bore size of two-stroke engines by 25%, enabling the vessel to reduce speed while the engine runs at optimal loads, with outstanding fuel and combustion efficiency. This cuts both fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. The bore size reduction is achieved with no changes to the engine frame and only matching part replacements on turbocharger installations. This simplifies the conversion process, limiting it to cylinder, piston and fuel injection components alongside an update to the engine automation system.

While Fit4Power is a significant project, it does not represent what IMO classes a ‘major conversion’, meaning that the derated engine does not need a new nitrogen oxide (NOx) certification. The engine’s original tier rating can be maintained and is confirmed by Wärtsilä after the project using its approved ‘shop test at sea’ methodology. This process avoids the time-consuming and costly process of running an equivalent engine on a testbed.

A retrofit project of this scale is an exercise in teamwork. Across the 17 vessels already installed by the end of the first quarter in 2025, Wärtsilä has developed close relationships with partners across the supply chain and with repair yards. The retrofit execution has been refined over time, allowing the current conversion to be completed in less than four weeks – comparing favorably to other technology installations and allowing operators to plan their regulatory compliance less than a year into the future.

Staying ahead of the curve

It is already clear that the benefits of the radical derating are well worth the effort. An engine retrofitted with the Fit4Power technology can deliver annual fuel savings of up to 2,000 tons and a reduction in CO2 emissions of 6,400 tons. In financial terms, this translates to potential yearly savings of two million euros, or more, in operational expenses, based on current fuel costs and carbon levies. Add to this an annual savings in parts, and the economic case for radical derating becomes compelling.

Fit4Power can cut fuel consumption and emissions by 10-15%. Across 17 vessels retrofitted since late 2022, Wärtsilä has saved operators a total of more than 25,000 tonnes of fuel, translating to 80,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions or more. Further translated into regulatory compliance terms, this buys operators a further three to five years of compliance with CII, giving them time to plan the next stage of their decarbonization investment strategy.

However, derating is more than just an interim measure. By making engines smaller and more efficient, operators are setting a new efficient baseline for the operation of their vessels, as well as paving the way for incremental steps towards decarbonization. For example, future conversion of the engines for methanol, LNG or ammonia fuel, using Wärtsilä’s Fit4Fuels platform, will enable the use of zero- or near-zero emissions fuels, and because the engine is already running at optimal efficiency, the cost of those expensive fuels will be minimized.

Slowing the speed of vessels can be a game-changing strategy as operators seek to reduce emissions. But slowing down the vessel need not mean slowing down the engine and all the inefficiencies that come with it. With Fit4Power, operators can sail full steam ahead into a future of lower emissions.

Andreas Wiesmann is General Manager of Strategy and Business Development for 2-stroke Engine Services at Wärtsilä Marine. This article is brought to you by Wärtsilä Marine.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment