SPACE/COSMOS

Distant super-massive black hole shows high velocity sign of over-eating

University of Leicester scientists describe how the capture of new matter formed a ring around the black hole, before being partly swallowed by the hole, with excess matter ejected as a high velocity wind

University of Leicester

A new University of Leicester study shows how the uncontrolled growth of a distant Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) is revealed by the ejection of excess matter as a high velocity wind.

Published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS), it describes for the first time how the black hole’s ‘over-eating’ of new matter led to the excess being ejected at nearly a third of the speed of light.

Powerful outflows of ionized gas have been a major interest of ESA’s XMM-Newton X-ray Observatory since first detected by Leicester X-ray astronomers in 2001, and subsequently recognized as a characteristic feature of luminous AGN.

A black hole is formed when a quantity of matter is confined in a sufficiently small region that its gravitational pull is so strong that nothing - not even light – can escape. The size of a black hole scales with its mass, being 3km in radius for a solar mass hole.

Real – astrophysical - black holes of stellar mass are common throughout the Galaxy, often resulting from the violent collapse of a massive star, while a supermassive black holes (SMBH) may lurk in the nucleus of all but the smallest external galaxies.

University of Leicester scientists conducted a 5-week study of an SMBH in the distant Seyfert galaxy PG1211+143 in 2014, about 1.2 billion light years away, using the ESA’s XMM-Newton Observatory, finding a counter-intuitive inflow that added at least 10 Earth masses to the black hole’s vicinity (MN 2018), with a ring of matter accumulating around the black hole being subsequently identified by its gravitational redshift (MN 2024).

The final part of this story now reports a powerful new outflow at 0.27 times the speed of light, launched a few days later, as gravitational energy released as the ring is drawn towards the hole heats the matter to several million degrees, with radiation pressure driving off any excess.

Professor Ken Pounds from the University of Leicester School of Physics and Astronomy, lead author of the three papers, commented: “Establishing the direct causal link between massive, transient inflow and the resulting outflow offers the fascinating prospect of watching a SMBH grow by regular monitoring of the hot, relativistic winds associated with the accretion of new matter.”

PG1211+143 was a target of University of Leicester X-ray astronomers, using the ESA’s XMM-Newton Observatory, from its launch in December 1999. An early surprise was detecting a fast-moving, counter-intuitive outflow, with a velocity 15% of light (0.15c), and the power to disrupt star formation (and hence growth) in the host galaxy. Later observations found such winds to be a common property of luminous AGN.

The availability of simultaneous ultra-violet fluxes from the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, a NASA mission which Leicester hosts the UK Swift Science Data Centre for, was – and will remain - critical in understanding the accretion process in SMBH.

Journal

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Article Title

Observing the launch of an Eddington wind in the luminous Seyfert galaxy PG1211+143

Article Publication Date

17-Jun-2025

Two European satellites mimic total solar eclipse as scientists aim to study corona

Dubbed Proba-3, the $210 million (€181 million) mission has generated 10 successful solar eclipses so far during the ongoing checkout phase.

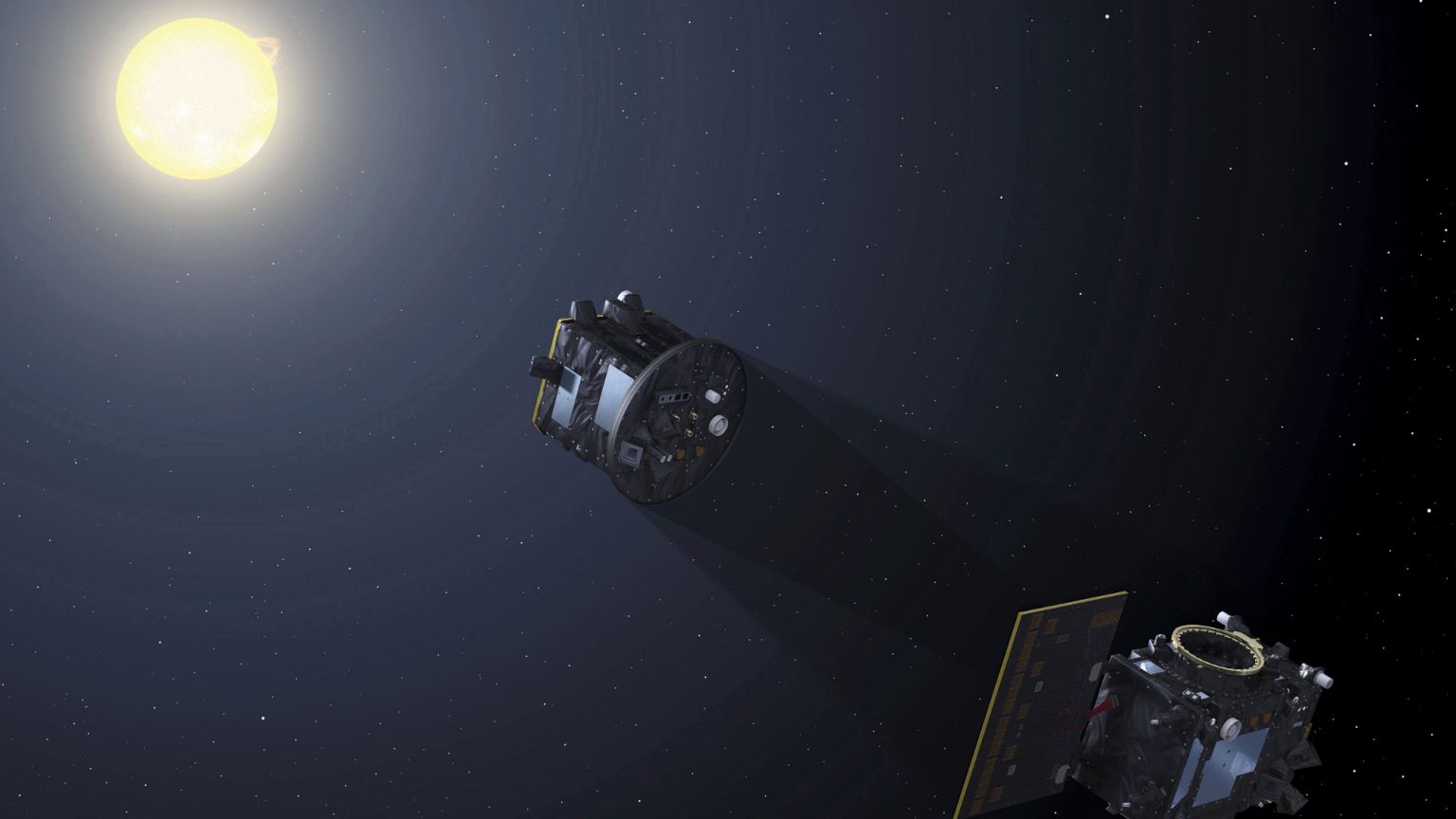

A pair of European satellites have created the first artificial solar eclipse by flying in precise formation, providing hours of on-demand totality for scientists.

The European Space Agency released the eclipse pictures at the Paris Air Show on Monday.

Launched late last year, the orbiting duo have churned out simulated solar eclipses since March while zooming tens of thousands of kilometres above Earth.

Flying 150 metres apart, one satellite blocks the sun like the moon does during a natural total solar eclipse as the other aims its telescope at the corona, the sun's outer atmosphere that forms a crown or halo of light.

It's an intricate, prolonged dance requiring extreme precision by the cube-shaped spacecraft, less than 1.5 metres in size.

Their flying accuracy needs to be within a mere millimetre, the thickness of a fingernail. This meticulous positioning is achieved autonomously through GPS navigation, star trackers, lasers and radio links.

Dubbed Proba-3, the $210 million (€181 million) mission has generated 10 successful solar eclipses so far during the ongoing checkout phase.

The longest eclipse lasted five hours, said the Royal Observatory of Belgium's Andrei Zhukov, the lead scientist for the orbiting corona-observing telescope. He and his team are aiming for a six-hour totality per eclipse once scientific observations begin in July.

Scientists are already thrilled by the preliminary results that show the corona without the need for any special image processing, said Zhukov.

"We almost couldn’t believe our eyes," Zhukov said in an email. "This was the first try, and it worked. It was so incredible."

Zhukov anticipates an average of two solar eclipses per week being produced for a total of nearly 200 during the two-year mission, yielding more than 1,000 hours of totality.

That will be a scientific bonanza since full solar eclipses produce just a few minutes of totality when the moon lines up perfectly between Earth and the sun, on average just once every 18 months.

The sun continues to mystify scientists, especially its corona, which is hotter than the solar surface.

Coronal mass ejections result in billions of tons of plasma and magnetic fields being hurled out into space. Geomagnetic storms can result, disrupting power and communication while lighting up the night sky with auroras in unexpected locales.

While previous satellites have generated imitation solar eclipses, including the European Space Agency and NASA's Solar Orbiter and Soho observatory, the sun-blocking disk was always on the same spacecraft as the corona-observing telescope.

What makes this mission unique, Zhukov said, is that the sun-shrouding disk and telescope are on two different satellites and therefore far apart.

The distance between these two satellites will give scientists a better look at the part of the corona closest to the limb of the sun.

"We are extremely satisfied by the quality of these images, and again this is really thanks to formation flying" with unprecedented accuracy, ESA's mission manager Damien Galano said from the Paris Air Show.

No comments:

Post a Comment