Whistleblower Reveals Colombia’s Oil Spill Coverups

- A BBC documentary and whistleblower allegations expose decades of unreported oil spills by Colombia’s state oil company Ecopetrol.

- Operations by foreign companies Gran Tierra and Amerisur in the Putumayo Basin have caused major ecological harm.

- Despite environmental promises, President Gustavo Petro’s administration has allowed oil operations to expand in the Amazon.

For decades, Colombia’s national government ignored transgressions involving the strife-torn country’s oil industry. A drill-at-all-costs mentality saw successive administrations, from the late-1980s, aggressively drive exploitation of Colombia’s hydrocarbon resources to boost the war-ravaged economy regardless of the fallout. This saw Bogota ignore a multitude of human rights abuses, severe environmental damage, and violent incidents which rocked the strife-torn nation. Even Colombia’s first leftist President Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla who was quick to flaunt his environmental credentials, appears to have abandoned the ecologically sensitive Amazon to the oil industry’s depredations.

Earlier this year, the United Kingdom’s national broadcaster, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), released a damning documentary alleging cover-ups of oil spills and other damaging incidents by Colombia’s scandal-prone oil industry. Former employee turned whistleblower, Andres Olarte, alleged Colombia’s national oil company, Ecopetrol, not only avoided reporting spills but concealed them while failing to remediate environmentally damaging incidents for decades. Olarte’s allegations align with claims, many emerging decades ago, from numerous communities in Colombia’s Middle Magdalena Valley and Amazon that oil companies, including Ecopetrol, are failing to report and clean up oil spills.

These are devastating allegations for Bogota because the petroleum is Colombia’s primary export, and Ecopetrol, of which 88.49% is government-owned, is a major source of fiscal revenue. In a shock development, the scandal-plagued administration of Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first leftwing President, appears to have abandoned the country’s Amazon to the depredations of the fiscally crucial petroleum industry. Petro, himself a former leftist guerrilla with the 19th of April Movement (M-19), celebrated plans to reduce Colombia’s dependence on hydrocarbons and bring petroleum exploration to an end. There are indications, however, that industry operations are expanding, especially in Colombia’s Amazon, a sizeable portion of which is situated in the departments of Putumayo and Caquetá.

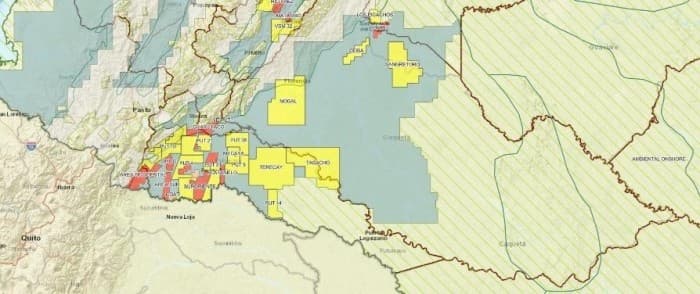

The Putumayo Basin, which contains significant petroleum industry operations, is located in Colombia’s south near in the border with Ecuador in Putumayo and Caquetá. This basin forms part of the larger Putumayo-Oriente-Maranon province, a sedimentary basin nestled against the Andes’ eastern flank extending from southern Colombia through Ecuador into northern Peru. While exploration efforts began in the early 1920s, it was then U.S. oil major Texaco that was responsible for a slew of major petroleum discoveries that by the 1960s had put the region on the global hydrocarbon production map. According to Colombia’s industry regulator, the National Hydrocarbon Agency (ANH), as of May 2025, there are 237 active oil blocks with 34 located in the Putumayo Basin across Putumayo and Caquetá.

Colombia Oil Block Map Putumayo and Caquetá

Source: National Hydrocarbons Agency.

Oil extraction in the Putumayo-Oriente-Maranon province has left a tragic legacy, particularly for the region’s indigenous peoples, with swathes of land and waterbodies polluted by hydrocarbon run-off. For decades, local communities complained about the contamination of water bodies, crops, and food sources with petroleum, causing serious ecological damage. Some of the worst environmental damage occurred in northern Ecuador, where Texaco and Ecuador’s then national oil company, Petroamazonas, are blamed by indigenous communities for what can only be described as horrendous pollution centered on the city of Nueva Loja, also known as Lago Agrio, a key Amazonian oil town near the border with Colombia.

The dispute centers on Texaco disposing of billions of barrels of oil waste in vast pits, which were then buried in the jungle. Afterwards, whenever it rains, the hydrocarbon residue bubbles through the soil, coating the ground with a thick black sludge that flows into waterways, wetlands, and farmland. Those complaints eventually emerged as an acrimonious, multi-billion-dollar, decades-long lawsuit involving supermajor Chevron, which had acquired Texaco in October 2001. Ultimately, Ecuador’s highest tribunal, the National Court of Justice, upheld a lower court judgment against Chevron but reduced the damages to $9.5 billion. While the judgement remains unpaid, with Chevron bitterly arguing the ruling resulted from corruption, with Texaco having fulfilled the required remediation, immense pollution from dumping billions of barrels of oil waste remains an acute problem in the area.

Across the border in Colombia, the oil industry in the Putumayo Basin is also responsible for a slew of environmentally damaging incidents since production began with the Orito discovery in 1963. Putumayo is among Colombia’s top oil-producing departments, ranked sixth pumping accumulated petroleum production of 3.5 million barrels thus far for 2025, with oil responsible for 29% of gross domestic product (GDP). Those numbers underscore the scale of industry operations in the department, explaining why oil spills and other environmentally damaging incidents remain a major risk.

Local communities, especially near the city of Puerto Asis, regularly complain of oil tainting waterbodies, including the Putumayo River, which is a tributary of the Amazon, wetlands, jungle, local water supplies, and crops. While it is difficult to obtain complete records showing the number of oil spills, data from Colombia’s National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA) shows 98 events occurring in Putumayo from the 2,129 recorded between 2015 and 2022. Nonetheless, local communities and environmental defenders claim the number is far greater, particularly with smaller leaks and other minor environmentally damaging events reputedly not being captured on official records held by Colombian authorities. Indeed, there is a long history of communities in Putumayo complaining of unremediated oil spills and repeatedly raising the alarm with Bogota, but without any concrete action taken by authorities.

There is considerable evidence supporting those claims, with Ecopetrol whistleblower Andres Olarte’s latest to emerge. He alleges that Colombia’s national oil company failed to report and remediate hundreds of oil spills over the last decade. While many of the 800 events divulged by Olarte occurred in the Middle Magdalena Valley, notably around the city of Barrancabermeja, the capital of Colombia’s oil heartland, many transpired in Putumayo. An April 2024 article published by Mongabay refers to at least 160 oil spills in the department caused solely by deteriorating pipeline infrastructure. The author contends that an over-dependence on oil revenues discourages local authorities from upgrading outdated pipelines, as this will reduce production due to the facilities being taken offline.

An April 2025 article from Colombian peace thinktank Rutas del Conflicto published by InfoAmazonas goes on to examine the impact of Colombia’s oil industry on indigenous communities in Putumayo. The author, Pilar Puentes, discusses in depth how petroleum waste from various oil spills and other environmentally damaging incidents has seeped into waterways, nearby jungle, and farmland to contaminate drinking water as well as food supplies. According to Puentes, the two oil blocks responsible for significant environmental and social impacts in Putumayo are Platanillo and PUT-1, which are both situated near the city of Puerto Asis and controlled by foreign energy companies. Block PUT-1 is controlled by intermediate Canadian driller Gran Tierra, while Platanillo is the property of Amerisur Resources a subsidiary of GeoPark, an independent energy company headquartered in Colombia, Argentin,a and Spain.

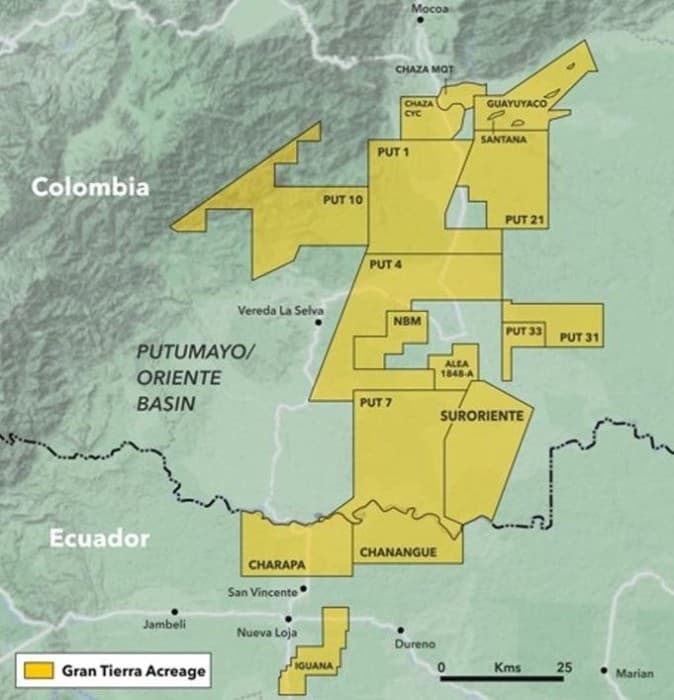

Gran Tierra holds interests in 22 Colombian oil blocks, with 13 located in Putumayo. The intermediate Canadian driller is regularly the subject of considerable controversy, which is centered on its Putumayo operations. There are frequent challenges against Gran Tierra’s operations by local indigenous communities, as well as regular oil spills.

Gran Tierra Energy Oil Blocks Putumayo, Colombia

The latest reported spill occurred in October 2024 when intruders entered a compound at the Costayaco-3 project and opened valves on several trucks, releasing an unspecified volume of crude oil into the jungle and nearby waterways. This was preceded by a series of spills from Gran Tierra’s Moqueta Costayaco transmission line pipeline, which was ruptured by a June 2023 explosion and experienced leaks in 2020 and 2021 due to faulty operating procedures.

Amerisur, which holds interests in 13 oil blocks in Colombia, with 12 located in Putumayo, is the subject of considerable controversy and is responsible for a range of oil spills as well as other environmental incidents in the country.

Map of Amerisur Oil Blocks in Colombia

The most recent environmental incident was the emission of Triethanolamine, a chemical emulsifier used in a range of extraction activities, from PAD 9 in the Platanillo Block in Putumayo. While that event is not significant, it demonstrates ongoing issues with operations in the Platanillo Block, which have earned considerable ire from local communities, notably the indigenous Siona people. Among the worst was a 2015 spill where FARC guerrillas forced drivers of tankers carrying Amerisur oil to dump their loads totaling 714 barrels or 30,000 gallons of petroleum into wetlands. This culminated in a lawsuit, which settled in 2023 with no admission of liability and the payment of undisclosed damages by Amerisur.

Local communities allege the Border Command, a powerful illegal armed group comprised of members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia’s (FARC) 32nd and 48th Fronts who spurned the 2016 peace agreement and former paramilitaries, is protecting Amerisur’s operations. In December 2020, the Inter-Church Commission for Peace and Justice heard from displaced peasants that the Border Command warned communities not to interfere with seismic work on Block PUT 8, which is 50% owned by Amerisur and SierraCol Energy. While the work was completed in 2021, ANLA suspended development in July 2025 at the request of the Siona Buenavista Reservation. The Siona are opposed to the development of the block, claiming it lies within the legally constituted boundaries of the Buenavista Reservation, which Amerisur rejects.

By Matthew Smith for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment