Geopolitical Tensions Drive U.S. Investment in Australian Rare Earths

- The United States is actively shifting its critical mineral sourcing strategy, with Australia becoming a key partner, as evidenced by the US Export-Import Bank's commitment of up to $200 million for VHM's Goschen Rare Earths and Mineral Sands Project in Victoria.

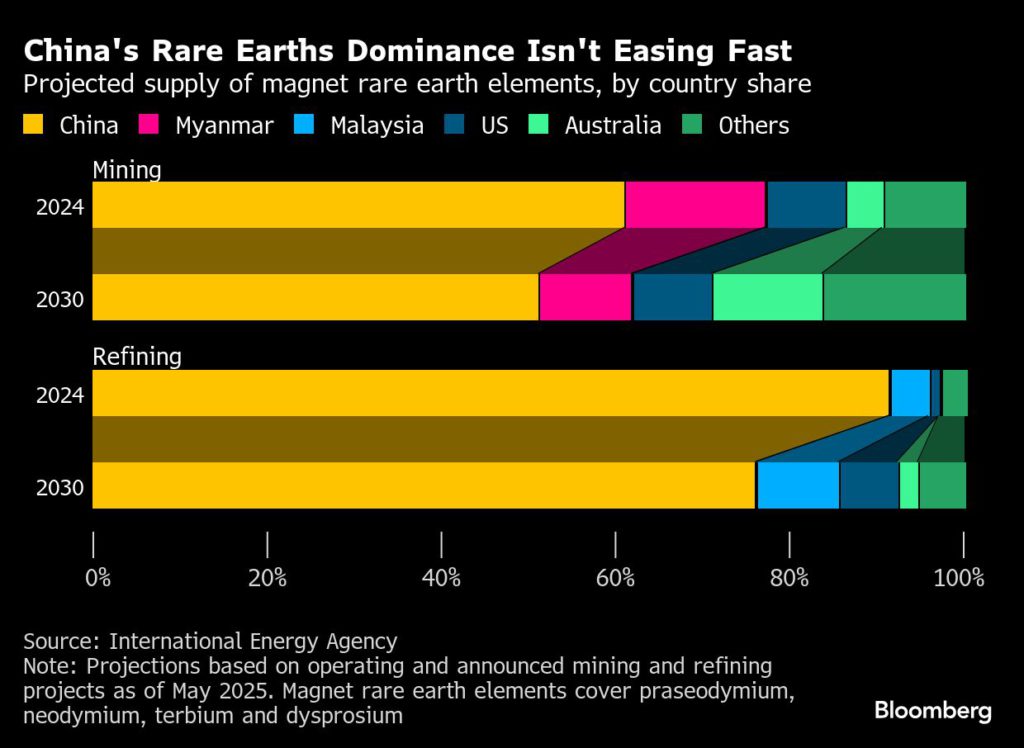

- This investment is part of Washington's "Supply Chain Resiliency Initiative," aimed at reducing reliance on China, which currently dominates over 80% of global rare earth processing, and follows a similar investment in Sunrise Energy Metals' scandium project.

- The Goschen project, with its substantial rare earth oxide reserves and valuable mineral sands, is strategically important for industries like electric vehicles and defense systems, and these investments are seen as a geopolitical move to secure long-term supply from trusted allies like Australia.

While geopolitical tensions continue and rare earths supply chain vulnerabilities deepen, the United States is quietly redrawing the global map of critical mineral sourcing, and Australia seems to be emerging as a cornerstone. The latest development on this front is the U.S. Export-Import Bank (EXIM) issuing a letter of interest to fund up to US $200 million for VHM’s Goschen Rare Earths and Mineral Sands Project in Victoria.

This follows a similar move in September of this year, when EXIM backed US $67 million for Sunrise Energy Metals’ scandium project in New South Wales. Both projects are now part of Washington’s “Supply Chain Resiliency Initiative,” which sources say is designed to reduce dependence on China. The latter country currently dominates over 80% of global rare earth processing.

A New Strategic Rare Earths Asset

The Goschen Rare Earths and Mineral Sands Project, developed by VHM Limited in northwest Victoria, is rapidly emerging as a strategic asset in the global race to secure critical minerals.

With over 413,000 tons of total rare earth oxide and a proven ore reserve of 199 million tons, Goschen is designed to supply both light and heavy rare earths. Alongside valuable mineral sands like zircon and rutile, these are essential for electric vehicles, defense systems and clean energy technologies.

The project has already cleared major regulatory hurdles, including environmental approvals and a mining license, and is positioned within a Tier 1 jurisdiction with robust infrastructure and logistics. Analysts note that its scalable design and dual revenue streams make it one of the most commercially and geopolitically attractive rare earth ventures outside of China.

One of Several Globally Significant Moves

VHM CEO Andrew King called EXIM’s decision a globally significant move to resolve current supply chain vulnerabilities. And it is not the only such endeavor. In September, the EXIM bank had issued a similar LoI to finance Sunrise Energy Metals’ Syerston scandium project, marking another strategic move to secure critical mineral supply chains outside China.

The funding would cover nearly half of the project’s development capital, pending the completion of a feasibility study, which is expected by late October. That analysis will incorporate updated ore reserve estimates as well as an optimized mine plan.

Part of a Strategic Realignment

Many experts following the rare earths sector believe these types of investments aren’t just financial, but geopolitical. By securing long-term supply from Australia, the U.S. is executing a “friend-shoring” strategy, rerouting critical inputs through trusted allies.

For the U.S., the supply of critical rare earths has recently become a matter of even greater concern. In April 2025, Beijing imposed export controls on several rare earth elements, effectively weaponizing its mineral dominance amid rising global tensions. American industries, from aerospace to semiconductors, depend on rare earths for magnets, batteries and precision components.

Now it seems the U.S. has found a strategic way to bypass China by using financing as foreign policy. By offering 12–15 year repayment terms and streamlining approvals via the Single Point of Entry framework with Australia, the U.S. is accelerating project viability and locking in future supply as part of its Supply Chain Resiliency Initiative.

A final investment decision on Goschen and Syerston is expected within months. When that happens, these projects will become part of America’s overall industrial policy. There could also be more U.S.-backed Australian lithium, cobalt and other rare earth projects in the future.

Meanwhile, in Greenland

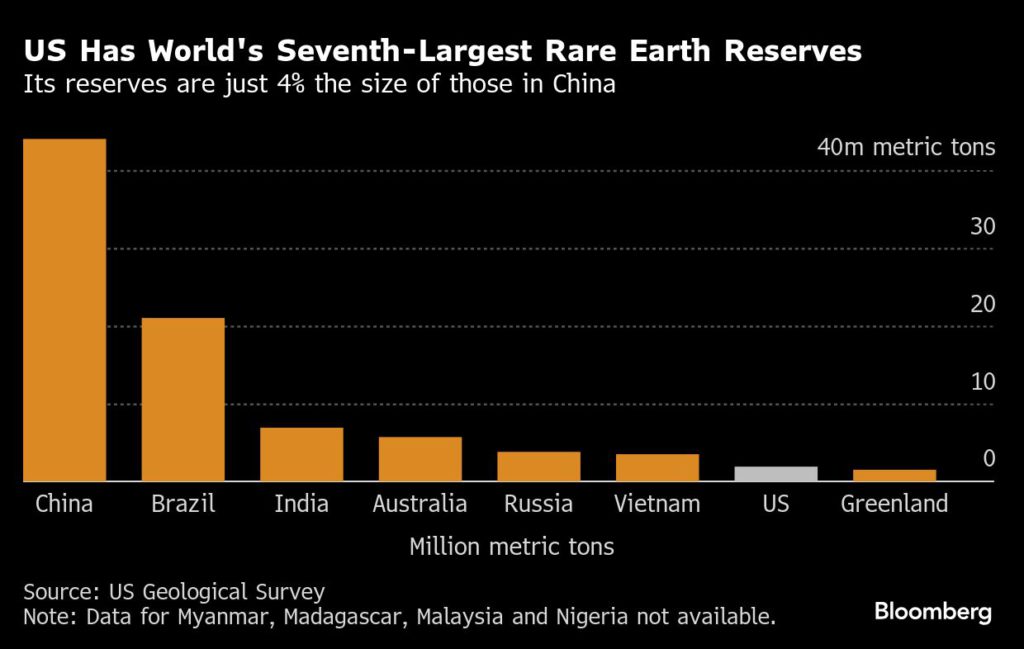

In addition to Australia, the U.S. has intensified its interest in Greenland’s rare earth reserves. For instance, the Tanbreez deposit is particularly valuable because it contains a high proportion of heavy rare earth elements, which are more scarce and critical for high-performance applications.

However, Greenland’s geopolitical significance adds another layer to this endeavor. As a semi-autonomous territory of Denmark located in the Arctic, it offers both resource potential and strategic positioning.

By Sohrab Darabshaw

Rare earth producers look to US-led boom to blunt China’s power

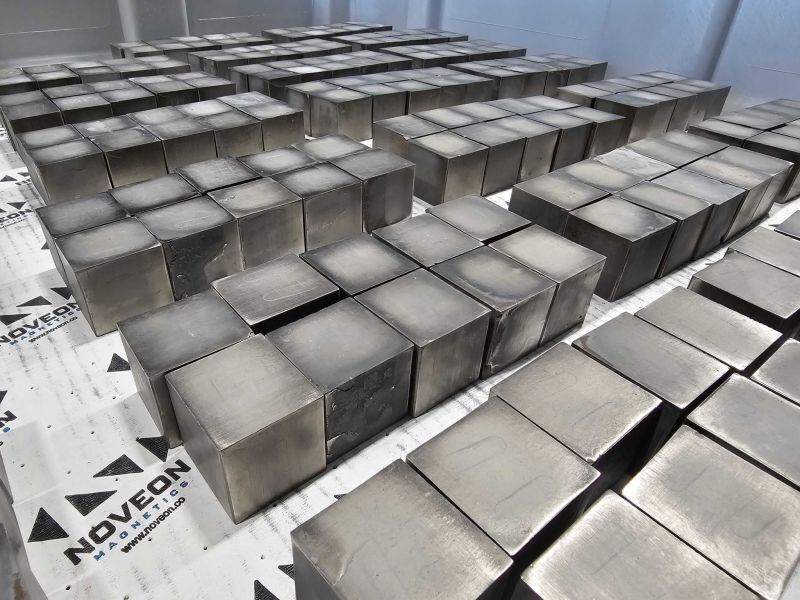

A Noveon Magnetics Inc. plant in Texas is at the vanguard of efforts to expand US supplies of the tiny but vital industrial components at the heart of a global trade showdown.

The company’s first facility, less than an hour from Austin, began selling rare-earth magnets commercially in 2023, after a decade of development. The operation is modest, but its ramp-up is emblematic of the shift taking place as the West scrambles to catch up with China’s vast rare-earths industry. After the Asian nation announced export controls earlier this year, Scott Dunn, Noveon’s co-founder, found himself inundated with calls.

“Not only were we being asked to do what we had planned, we were asked to increase those volumes for what was planned by multiples,” said Dunn, whose company has inked deals with customers from carmaker General Motors Co. to automation company ABB Ltd.

China, which produces the bulk of rare earths globally, unveiled supply curbs in April in response to a barrage of tariffs imposed by Washington. It outlined plans to expand the curbs this month, including by requiring overseas shippers of items that contain even small amounts of certain rare earths to have an export license. The fate of those measures remains unclear after US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said he expects China to offer a deferral of its curbs to seal a trade deal. President Donald Trump and his counterpart Xi Jinping are set to meet for trade talks later this week, and rare earths will be on the agenda.

Whatever happens, industry is betting the world won’t want to go back to one supplier. Conversations with more than a dozen rare earth executives and industry veterans describe a commercial landscape that is nascent but rapidly transforming as investor interest surges and governments — especially the US — launch more meaningful efforts to build a non-China supply chain.

Critical minerals consultancy Adamas Intelligence says that on paper, a wave of US magnet facilities underway could bring capacity high enough to offset imports by 2028. That requires everything to go to plan and operate at full tilt, and it won’t be a lasting fix as demand overtakes supply growth.

Still, it begins to suggest a path toward a meaningful and viable industry — even if it that goal is distant, thanks to the years it takes to build up mines, the expertise and technology required to produce magnets, and China’s decades-long lead.

“This year has been exhilarating, daunting, stressful, exciting, all of the adjectives,” James Litinsky, chief executive officer of MP Materials Corp., said in an interview.

MP operates the sole American rare earths mine. It received a landmark $400 million investment from the Pentagon in July, helping the company fund a new magnets plant in a deal that came with guaranteed purchases at minimum prices and effectively creating a national champion.

Government support was dialed up a notch this month, when Washington and Canberra agreed to jointly invest in Australian mines and processing projects. Both countries also pledged using trade measures like floor prices to help ward off competition.

Those deals signal a change in approach, with the rise of meaningful state support and intervention. Rare earth stocks globally have roared higher in response, sometimes to valuation levels that imply dramatic and almost improbable growth.

“To attract investors you need to do two things — to increase returns, but also to decrease risk,” said Nick Myers, chief executive officer of Phoenix Tailings, a rare earths refiner. “By saying another group like the US government is there with big dollars, that de-risks the space significantly.”

All of this is reminiscent of China’s playbook, said Ryan Castilloux, Adamas’s managing director. The country’s rare earths industry is highly regulated and state-dominated. Beijing has long supported strategic enterprises, either directly or through indirect means like inexpensive loans or a helping hand with permits, a far cry from the West’s economically driven approach.

“This moment creates discomfort for some, but I think it’s hard to argue that the alternative approach was bearing fruit,” he said. “Something new was needed.”

Rare earths, a group with obscure names like neodymium and samarium, are predominantly used to make super-strong, heat-resistant magnets. The governments’ interest stems from the sheer number of products that rely on them, from smartphones and vacuum cleaners to fighter jets.

Late last month, at the sector’s biggest gathering since China’s trade restrictions began, a canine-like robot called Spot — made by Boston Dynamics Inc. — posed and shook “paws” with attendees during a coffee break. That followed a speech by a former Canadian fighter pilot now running drone manufacturer Horizon Aircraft.

Magnets are essential in such industries because of the power they can deliver relative to their size and weight. In robots, magnets embedded in compact motors allow for precision and versatile movements; in missiles or drones, they’re essential in fine-caliber steering for a direct hit.

The industry has been on edge, waiting for more policy measures.

“I talk to folks in the administration frequently enough to know that a copy-and-paste of the MP deal is probably not going to happen,” Abigail Hunter, executive director of the SAFE Center for Critical Minerals Strategy, told the Rare Earth Mines, Magnets and Motors conference in Toronto. “But the important thing is the interest to meet the market and the companies with their specific challenges, to make sure that they’re sufficiently insulated and ultimately able to survive.”

The question is how much the West can really do, and how fast. China is home to half the world’s rare earth reserves and much of its refining capacity. The Asian nation began scaling up in the 1980s and now sells more than 90% of all rare earth magnets.

Previous crises, like China’s 2010 embargo of exports to Japan, triggered a wave of global enthusiasm but did not ultimately crack Beijing’s dominance. Building a new mine can take eight to 10 years, and refineries about five, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts said in a note.

Today, the sector is far smaller than almost any industrial metal — with production worth about $6.5 billion in 2024, according to Goldman, 33 times smaller than the copper market. The trade is also opaque and illiquid, curbing miners’ ability to hedge against price volatility.

Still, supply disruptions have immediate and far-reaching impact. Following China’s initial curbs in April, Ford Motor Co. temporarily shut a Chicago factory after running short of rare earth components, and assembly of Tesla Inc.’s Optimus humanoid robot was also hit. The European Union’s Chamber of Commerce in China said shortages caused seven production stoppages at companies in the bloc in August, and more are expected.

Even with the palpable enthusiasm in the corridors of the Toronto gathering, there’s no guarantee that planned American and other non-China plants underway will all be built on time — or able to deliver against wide-ranging customer requirements, given the complex processes involved in rare earth magnets.

“There’s not a cookbook for magnet production,” said David S. Abraham, a professor at Boise State University. “There’s time needed to ensure the product you are selling to customers meets their exact specifications.”

Noveon recently signed an accord with Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths Ltd. to collaborate on sourcing light and heavy rare earths and supply magnets for the US defense and commercial sectors. This year, the flood of inquiries the company received left it turning down more than it could pick up. Across the industry, Dunn acknowledged, installed capacity doesn’t equate to immediate capability.

“You’re dealing with requirements that are the result, in some cases, of decades of what China has delivered,” he said.

Sourcing so-called heavy rare earths, many of which were hit in the April restrictions, is another hindrance to further expansion. The metals are used as additives in magnetic materials to ensure performance even at high temperatures, but most come from China, or conflict-ridden parts of neighboring Myanmar, and are refined there.

Ultimately, it’s unclear if customers will be willing to bear the expense. Measures like floor prices for producers, intended to incubate the industry as it emerges, come at a cost for consumers. While some may in theory accept that as a hedge against geopolitical risk, government goals do not always align with those of purchasing managers. Several industry veterans said China would ultimately continue to dominate given its technical expertise, low costs and depth of supply offerings.

Still, entrepreneurs are jumping at the opportunity to promote alternatives to China.

In the US, a string of magnet facilities are in progress, including from USA Rare Earth Inc., Vulcan Elements Inc., Germany’s Vacuumschmelze GmbH & Co. KG, and South Korea’s JS Link Inc.

Others are working to reuse what is already out there. Cyclic Materials Inc., whose backers include Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp., aims to start producing magnet materials at a Canadian recycling facility next year.

At the Toronto event, a series of panels showcased companies developing projects from Africa to Australia. Adamas sees global use for rare earth magnets growing at 9% per annum over the next 10 years. Total US demand by 2033 will be five times today’s level, and demand in Europe will more than double.

By using the long-threatened critical mineral weapon once again in advance of this week’s talks, China has undoubtedly encouraged production outside its borders, and even collaboration. Trump is looking to sign critical minerals deals with trading partners during his trip to Asia, and that is unlikely to change even if a trade agreement is reached between Washington and Beijing.

At Noveon in Texas, Dunn is working to build magnet production up to the plant’s current annual capacity of 2,000 tons. There’s a burden on the many aspiring players outside China — and across all parts of the supply chain— to prove they can deliver, he said.

Customers want to know “that there is some sort of visibility and certainty and stability that they can pin their near-term future on,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment