China’s Emissions Flatline Amid Record Clean-Energy Growth

- China’s CO? emissions held steady for the third quarter of 2025 even as electricity use grew more than 6%, thanks to rapid solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear expansions.

- Transportation and heavy-industry emissions declined, while EV sales surpassed 50% of new cars, though chemical-sector emissions rose sharply.

- The plateau comes as Beijing sharpens its climate strategy ahead of COP30, raising the possibility that China is nearing a structural emissions peak.

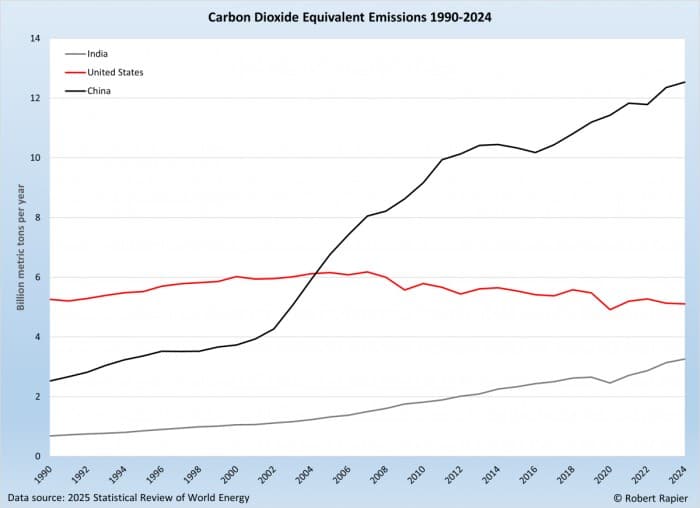

For a quarter century, China has been the dominant driver of rising global carbon emissions. Its rapid industrialization, swelling electricity demand, and unprecedented construction boom have shaped the world’s carbon trajectory more than any other country.

But the latest data show something atypical on China’s relentless climb higher: a pause.

New analysis from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) shows that China’s CO? emissions were essentially flat in the third quarter of 2025 compared to the year before. That marks roughly a year and a half of either flat or declining emissions, a trend that began in March 2024. For the world’s largest emitter, stability is newsworthy.

The real question is whether this moment represents a structural shift, since twice in the past 15 years China’s emissions paused for a breather only to once again turn higher.

- China’s CO? emissions held steady for the third quarter of 2025 even as electricity use grew more than 6%, thanks to rapid solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear expansions.

- Transportation and heavy-industry emissions declined, while EV sales surpassed 50% of new cars, though chemical-sector emissions rose sharply.

- The plateau comes as Beijing sharpens its climate strategy ahead of COP30, raising the possibility that China is nearing a structural emissions peak.

For a quarter century, China has been the dominant driver of rising global carbon emissions. Its rapid industrialization, swelling electricity demand, and unprecedented construction boom have shaped the world’s carbon trajectory more than any other country.

But the latest data show something atypical on China’s relentless climb higher: a pause.

New analysis from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) shows that China’s CO? emissions were essentially flat in the third quarter of 2025 compared to the year before. That marks roughly a year and a half of either flat or declining emissions, a trend that began in March 2024. For the world’s largest emitter, stability is newsworthy.

The real question is whether this moment represents a structural shift, since twice in the past 15 years China’s emissions paused for a breather only to once again turn higher.

A Plateau with Deeper Drivers

What makes this development notable is what didn’t happen. China’s power consumption did not stagnate. Quite the opposite: electricity demand rose 6.1% in Q3, accelerating from 3.7% growth in the first half of the year. Historically, that kind of increase would have triggered a corresponding rise in coal use and emissions.

This time, it didn’t.

A surge in low-carbon generation—solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear—absorbed almost all of the additional demand. China’s record-setting pace of renewable deployment has quietly transformed its grid. Gigawatt-scale solar farms are coming online at a clip unmatched anywhere else in the world. Wind installations, particularly offshore, have expanded quickly. Hydropower output rebounded after two difficult years of drought, and nuclear capacity continues to grow with a steady pipeline of new reactors.

Transportation emissions also moved in a different direction, falling 5% from a year earlier. The shift is largely driven by electric vehicles, where China dominates global sales. With more than 50% of new cars in China now electric, the country’s roads are becoming an important piece of its emissions equation. Heavy industry—especially steel and cement—also posted declines, helped by efficiency gains and a gradual pivot away from the most carbon-intensive construction activity.

Taken together, these changes may give the plateau real substance. They are not simply the result of a soft economy or temporary disruptions.

What makes this development notable is what didn’t happen. China’s power consumption did not stagnate. Quite the opposite: electricity demand rose 6.1% in Q3, accelerating from 3.7% growth in the first half of the year. Historically, that kind of increase would have triggered a corresponding rise in coal use and emissions.

This time, it didn’t.

A surge in low-carbon generation—solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear—absorbed almost all of the additional demand. China’s record-setting pace of renewable deployment has quietly transformed its grid. Gigawatt-scale solar farms are coming online at a clip unmatched anywhere else in the world. Wind installations, particularly offshore, have expanded quickly. Hydropower output rebounded after two difficult years of drought, and nuclear capacity continues to grow with a steady pipeline of new reactors.

Transportation emissions also moved in a different direction, falling 5% from a year earlier. The shift is largely driven by electric vehicles, where China dominates global sales. With more than 50% of new cars in China now electric, the country’s roads are becoming an important piece of its emissions equation. Heavy industry—especially steel and cement—also posted declines, helped by efficiency gains and a gradual pivot away from the most carbon-intensive construction activity.

Taken together, these changes may give the plateau real substance. They are not simply the result of a soft economy or temporary disruptions.

A Global Story in the Making

The timing of China’s emissions freeze stands in contrast with broader global trends. The latest Global Carbon Budget projects a 1.1% rise in fossil-fuel emissions worldwide in 2025, fueled by aviation, shipping, and growing energy demand in developing economies. Against that backdrop, China’s leveling off may offer a counterweight—and potentially the beginnings of a long-anticipated global peak.

But as with most climate milestones, the picture is mixed.

Emissions from China’s chemical sector jumped sharply in Q3, offsetting progress in other areas. And while the headline numbers are encouraging, they remain vulnerable to economic and policy swings. China has never hesitated to lean on heavy industry and coal generation during periods of stimulus or supply-chain stress, and it could do so again.

The timing of China’s emissions freeze stands in contrast with broader global trends. The latest Global Carbon Budget projects a 1.1% rise in fossil-fuel emissions worldwide in 2025, fueled by aviation, shipping, and growing energy demand in developing economies. Against that backdrop, China’s leveling off may offer a counterweight—and potentially the beginnings of a long-anticipated global peak.

But as with most climate milestones, the picture is mixed.

Emissions from China’s chemical sector jumped sharply in Q3, offsetting progress in other areas. And while the headline numbers are encouraging, they remain vulnerable to economic and policy swings. China has never hesitated to lean on heavy industry and coal generation during periods of stimulus or supply-chain stress, and it could do so again.

Policy Signals Behind the Numbers

The plateau also comes as Beijing recalibrates its climate strategy. In November, Chinese officials reaffirmed two major national targets: peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060. What stood out this time was the explicit inclusion of methane and nitrous oxide—non-CO? gases that had received less policy attention in previous plans. Addressing those emissions suggests China is ready to embrace a more comprehensive approach to climate governance.

This policy shift arrives at a strategically important moment. The emissions data emerged just as COP30 convened in Belém, Brazil, where global negotiators are wrestling with the realities of decarbonization. China’s ability to show progress—without sacrificing economic momentum—strengthens its diplomatic hand during climate negotiations.

The plateau also comes as Beijing recalibrates its climate strategy. In November, Chinese officials reaffirmed two major national targets: peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060. What stood out this time was the explicit inclusion of methane and nitrous oxide—non-CO? gases that had received less policy attention in previous plans. Addressing those emissions suggests China is ready to embrace a more comprehensive approach to climate governance.

This policy shift arrives at a strategically important moment. The emissions data emerged just as COP30 convened in Belém, Brazil, where global negotiators are wrestling with the realities of decarbonization. China’s ability to show progress—without sacrificing economic momentum—strengthens its diplomatic hand during climate negotiations.

What to Watch in the Months Ahead

Whether this plateau hardens into a true peak depends on several moving pieces:

- Renewable buildout and grid integration. China’s renewable pipeline is enormous, but transmission bottlenecks and curtailment remain challenges.

- Industrial enforcement. Steel, cement, and chemicals will determine whether efficiency gains can be sustained.

- EV adoption and infrastructure. EV momentum has carried transportation emissions lower, but charging capacity and consumer incentives will shape the next phase.

- Commodity cycles and export demand. If construction or manufacturing rebounds sharply, emissions could easily follow.

For investors, policymakers, and anyone modeling long-term climate risk, China’s emissions sit at the center of the global carbon outlook. The coming quarters will reveal whether this is a fleeting plateau—or the start of a critical pivot in the world’s emissions trajectory.

Whether this plateau hardens into a true peak depends on several moving pieces:

- Renewable buildout and grid integration. China’s renewable pipeline is enormous, but transmission bottlenecks and curtailment remain challenges.

- Industrial enforcement. Steel, cement, and chemicals will determine whether efficiency gains can be sustained.

- EV adoption and infrastructure. EV momentum has carried transportation emissions lower, but charging capacity and consumer incentives will shape the next phase.

- Commodity cycles and export demand. If construction or manufacturing rebounds sharply, emissions could easily follow.

For investors, policymakers, and anyone modeling long-term climate risk, China’s emissions sit at the center of the global carbon outlook. The coming quarters will reveal whether this is a fleeting plateau—or the start of a critical pivot in the world’s emissions trajectory.

Column: China burns more coal even as output slips, driving prices up

China’s electricity generation from thermal fuels such as coal jumped in October while coal output declined, leading to higher prices for both domestic fuel supplies and imports.

Signs point to further price rises as the world’s second-largest economy enters the peak season for energy demand, and with Chinese mines hobbled by nationwide output restrictions amid ongoing safety checks, more of that coal will need to come for overseas.

Fossil fuel power generation rose to 513.8 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) in October, up 7.3% from the same month a year earlier and the highest for an October in records going back to 1998. China’s thermal power output is mostly from coal with a small amount from natural gas.

Overall electricity generation in October also rose to the highest for three decades for the same month, reaching 800.2 billion kWh, up 7.9% from a year earlier, according to official data released on November 14.

In addition to stronger thermal generation, hydropower output jumped 28.2% from a year earlier, while wind generation rose slightly and solar power dropped on weaker irradiance in the northeast and northwest.

With hydropower generation unlikely to rise further in November and solar and wind entering seasonal downturns, it is likely that coal-fired generation will have to increase for the upcoming winter demand peak.

This may put some pressure on domestic coal mines, which have reported lower production amid Beijing’s “anti-involution” campaign aimed at combating overcapacity in several key strategic industries.

China’s output of all grades of coal was 406.75 million metric tons in October, down 2.3% from the same month in 2024 and also down from 411.51 million tons in September, according to official data released on November 14.

Robust coal production in the first half of the year means that overall output for the first 10 months of the year is still up 1.5% from the year-earlier period.

However, the restrictions on output in recent months have sparked higher domestic prices, with consultants SteelHome assessing thermal coal at Qinhuangdao port at 835 yuan ($117.44) a ton on Wednesday.

The price has jumped 37% to a one-year high from the four-year low of 610 yuan a ton hit in June.

Seaborne gains

Higher domestic prices are dragging up seaborne thermal coal prices from China’s major suppliers, Indonesia and Australia.

Indonesian coal with an energy content of 4,200 kilocalories per kilogram (kcal/kg) rose to a six-month high of $48.52 a ton in the week to November 14, according to an assessment by commodity price reporting agency Argus.

Australian 5,500 kcal/kg coal jumped to $86.53 a ton in the week to November 14, an 11-month high and up 32% from the four-year low of $65.72 hit in early June.

The rising prices are likely to prove a boon for coal exporters as China’s import volumes are holding up despite the increased cost of cargoes.

China’s seaborne thermal coal imports are forecast to reach 28.63 million tons in November, down a touch from October’s 29.2 million, according to data compiled by analysts DBX Commodities.

Imports of seaborne thermal coal have recovered since hitting a three-year low of 20.02 million tons in June, according to DBX data, with the four months from August to November all coming in just either side of 29 million tons.

China’s stockpiles of coal at coastal ports are estimated by DBX to drop to 63 million tons in November, down from 64.4 million in October and also around 16 million below the level from November last year.

This suggests that demand for seaborne coal will likely be resilient over the winter period, especially if domestic output remains constrained.

(The views expressed here are those of the author, Clyde Russell, a columnist for Reuters.)

China’s coal miners hope spot price rally lifts annual contracts

Chinese miners are hoping a recent rally in spot prices for thermal coal will translate into a boost for their annual contracts with power plants next year.

Miners are required to sell 75% of their coal on annual contracts, and the next few weeks will be a pivotal period on those negotiations. The National Development and Reform Commission is pushing miners and utilities to settle such deals by Dec. 13, the China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association said in a Wednesday note, citing an unpublished notice from the regulator.

That makes the recent rally a godsend for miners. Spot prices have surged 36% since June as increased safety inspections reduced output and an October heat wave led to a surge in coal power generation to run air conditioners. Qinhuangdao 5,500-kilocalorie coal is trading at 827 yuan ($116.20) a ton, according to China Coal Resource, the highest level in a year and well above the 675 yuan benchmark for 2025 annual contracts.

Inventory levels across the supply chain are below seasonal levels, which could exert more upward price pressure through mid-December, with a potential peak at 850 to 900 yuan a ton, said Feng Dongbin, vice president at consultant SXCoal, according to a Tuesday research note from Morgan Stanley analysts.

Feng expects total coal imports to fall to 480 million tons in 2026, from a projected 493 million tons this year. Mongolia, one of China’s major suppliers, proposed lifting its exports to 100 million tons next year. Prime Minister Zandanshatar Gombojav made the proposal at a Tuesday meeting in Moscow with Chinese premier Li Qiang.

No comments:

Post a Comment