Japan Won’t Quit Russian Oil and Gas

Crude oil and natural gas from overseas, including Russia, are important for Japan’s energy security, the country’s economy ministry told Reuters this week, noting the Sakhalin-1 oil and gas project in Russia’s Far East.

“Japan government continues to recognize that securing energy from overseas, including the Sakhalin Project, is extremely important for Japan's energy security,” the statement said. “We will take necessary measures to ensure that Japan's stable energy supply is not compromised,” the ministry also said.

Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry was responding to a question by Reuters regarding the latest U.S. sanctions on Rosneft, Russia’s biggest oil producer and a shareholder in the Sakhalin-1 project, which also has the Japanese economy ministry as a shareholder. The project used to be operated by Exxon, but the supermajor left Russia in 2022.

Rosneft has 20% in Sakhalin-1, India’s ONGC Videsh holds another 20%, and a Japanese consortium comprising the economy ministry and several energy companies holds 30%. When the sanction barrage on Russia started following its invasion of Ukraine, the Japanese companies and the ministry were granted an exemption from the punitive action due to the country’s overwhelming dependence on foreign energy commodities.

Since then, Japanese government officials have repeatedly stated Japan would find it difficult to quit Russian energy. Besides Sakhalin-1, which exports crude oil to Japan, the country also buys liquefied natural gas from the Sakhalin-2 project. Russian LNG accounts for about 9% of Japan’s total liquefied natural gas imports. Utility JERA imports the gas from Sakhalin-2 under contracts expiring in 2026 and 2029

Last month, following President Donald Trump’s suggestion that Japan stop buying Russian energy commodities, the government reiterated its stance, with the economy minister noting the country had been “steadily reducing its dependence on Russian energy.”

By Irina Slav for Oilprice.com

India’s Nayara Energy Defies Sanctions With Record Russian Intake

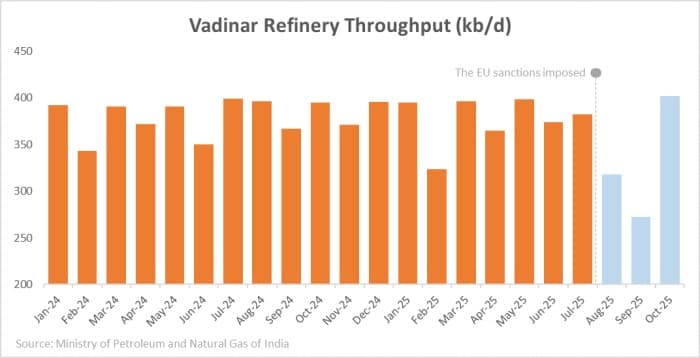

- Crude intake at Nayara’s 400,000-b/d Vadinar refinery plunged to just 240,000 b/d after EU and US sanctions hit in August, but rebounded to 420,000 b/d in November.

- Despite the U.S. sanctions wind-down deadline on 21 November, two Aframax tankers from Rosneft’s Ust-Luga terminal arrived at Vadinar since.

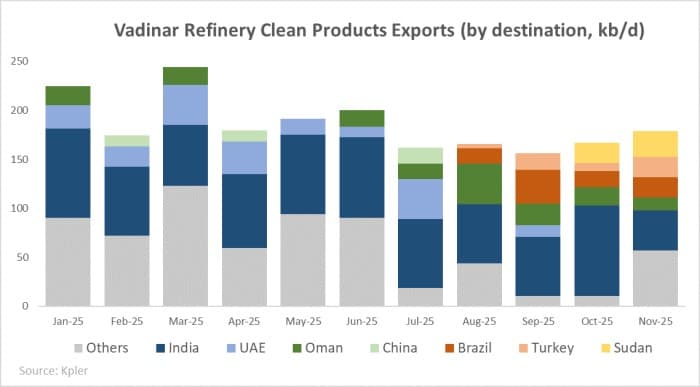

- With traditional outlets constrained, Nayara lifted domestic sales to almost 100,000 b/d in October, and opened new export markets from Brazil and Turkey to Sudan.

Nayara Energy has spent the past four months navigating one of the most complicated sanction environments in its history, yet instead of retreating, the Rosneft-backed refiner is quietly re-wiring its entire crude-sourcing and fuel-export strategy. After EU sanctions in July forced its 400,000 b/d Vadinar refinery to slash throughput, and October’s US sanctions on Rosneft added further pressure, Nayara’s crude imports briefly collapsed to just 240,000 b/d, sourced from exclusively Russian suppliers. But by October and November, the company had staged a dramatic rebound, pushing intake back up to 390,000 b/d and then 420,000 b/d – exceeding even the refinery’s nominal nameplate capacity. By simultaneously deepening domestic sales and cultivating new buyers from Brazil to Sudan, Nayara appears to have found a way to turn sanctions risk into a trading opportunity, even as the official US sanctions wind-down deadline passed on 21 November and tankers from Russia’s Baltic Sea ports continued to dock at Vadinar undeterred.

After the EU imposed sanctions on Nayara Energy’s Vadinar refinery in July (citing its association with Russian crude supplied via Rosneft, which holds a 49% stake), the company struggled to keep the refinery running at normal rates. The measures triggered logistical disruptions, pushed away most vessel owners, and forced Nayara to scale back utilisation rates sharply. As Iraqi and Saudi suppliers refused to supply contracted volumes to Nayara, crude imports into Vadinar in August sank to 240,000 b/d, the lowest level in months, marking the first time the refinery was entirely reliant on Russian grades.

Related: Oil Prices Sink as Ukraine Agrees to Peace Deal

On the face of it, the pressure on Nayara was supposed to deepen when Washington sanctioned Rosneft in October. However, by late October, it became clear that Vadinar is bouncing back to strength rather than faltering. With its 400,000 b/d nameplate capacity as a benchmark, Nayara ramped up intake of Russian crude to 390,000 b/d that month, and then lifted imports further to 420,000 b/d in November to date – effectively running the plant at 105% capacity.

The official US sanctions wind-down period expired on 21 November, before which all buyers of Rosneft and Lukoil crude or products were required to conclude transactions. Yet Vadinar’s behavior suggested no intention of slowing down. Two Aframax tankers, both loaded at Russia’s Ust-Luga terminal for Rosneft, arrived at Vadinar on 22 and 24 November, indicating that sanctions alone were insufficient to interrupt flows.

In August, the core question facing Nayara was no longer how to buy Russian crude, but where to sell its refined products. The company’s sharp decline in throughput and exports that month was partly the result of blocked outlets, as sanctions sealed off the Europen market altogether. The first, most reliable fallback was India itself: Nayara’s network of 6,500 retail stations (with another 400 outlets planned) offered an available channel to absorb its gasoline and diesel.

Then came an unexpected lifeline. In October, state-run Hindustan Petroleum Corporation (HPCL) reported operational problems at its Mumbai refinery after processing domestic crude with unusually high salt and organic chloride content, which led to corrosion in downstream units. Nayara stepped into the gap. Shipments of gasoline and gasoil to HPCL surged, helping lift domestic deliveries to around 90,000 b/d in October, according to Kpler.

With domestic channels strengthened, Nayara moved to diversify export outlets beyond India. Roughly a third of its November clean-products cargoes were directed to ship-to-ship hubs such as Fujairah (UAE) and Sohar (Oman) – a strategy commonly used to obscure final destinations in sensitive trades.

But the most striking change came from the emergence of new customers, notably Brazil and Turkey – countries that did not appear in Nayara’s client list over the past three years. In November so far, Nayara exported 21,000 b/d of clean products to Brazil and another 21,000 b/d to Turkey. These flows almost certainly reflect disruptions in Russian diesel exports after intensified Ukrainian drone strikes on Russian refineries, coupled with rising compliance risks for traders buying directly from Russia. Because Vadinar has processed exclusively Russian crude since August, its products offer these markets a politically safer, operationally simpler way to access the same molecules.

Yet the most consequential addition to Nayara’s portfolio may be Sudan. Since October, the Vadinar terminal has dispatched four cargoes totalling 1.3 million barrels of clean products to Sudanese ports. With Sudan engulfed in civil war and its only major refinery – the 100,000 b/d Khartoum (Al-Jaili) facility – destroyed in the summer of 2023, the country is entirely dependent on imports. Potential discounts on products refined from Russian oil make Vadinar an obvious supplier. Sudan, and other fragile markets across East Africa, have little incentive to observe Western sanctions, making them ideal long-term buyers for Nayara’s output.

Still, securing crude supplies might become increasingly challenging under full US sanctions. Nayara may attempt to insulate itself through smaller, opaque trading houses, using them as intermediaries to avoid purchasing directly from Rosneft.

Whether this workaround can be scaled is uncertain. But for now, Nayara Energy is demonstrating that a combination of discounted Russian crude, flexible logistics, opportunistic trading, and an expanding footprint in both domestic and sanctions-agnostic markets can keep one of India’s largest refineries running near full tilt – even as Western sanctions close in from both sides. Paradoxically, the pressure may be accelerating a broader shift: Western restrictions are pushing companies linked to Russian oil producers into new geographies, opening fresh trade routes, and supplying developing economies with cheaper fuel at a moment when they need it most. These developing markets gain more incentive to boost imports of discounted flows and give themselves a commercial edge, while many of the former Western buyers now find themselves managing the opposite outcome: higher prices, fewer sanction-free suppliers, and a tightening pool of accessible energy.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment