Sanders Champions Those Fighting Back Against Water-Sucking, Energy-Draining, Cost-Boosting Data Centers

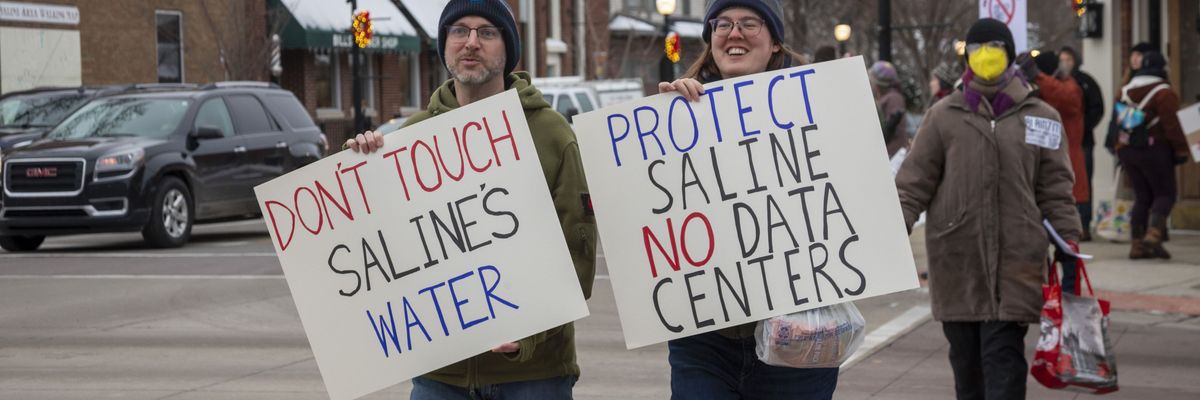

Residents rally against the $7 billion Stargate data center planned on farmland in Saline, Michigan on December 1, 2025.

(Photo by Jim West/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Julia Conley

Dec 10, 2025

COMMON DREAMS

Americans who are resisting the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers in their communities are up against local law enforcement and the Trump administration, which is seeking to compel cities and towns to host the massive facilities without residents’ input.

On Wednesday, US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) urged AI data center opponents to keep up the pressure on local, state, and federal leaders, warning that the rapid expansion of the multi-billion-dollar behemoths in places like northern Virginia, Wisconsin, and Michigan is set to benefit “oligarchs,” while working people pay “with higher water and electric bills.”

230+ Environmental Groups Call On Congress to Impose Moratorium on New AI Data Centers

“Americans must fight back against billionaires who put profits over people,” said the senator.

In a video posted on the social media platform X, Sanders pointed to two major AI projects—a $165 billion data center being built in Abilene, Texas by OpenAI and Oracle and one being constructed in Louisiana by Meta.

The centers are projected to use as much electricity as 750,000 homes and 1.2 million homes, respectively, and Meta’s project will be “the size of Manhattan.”

Hundreds gathered in Abilene in October for a “No Kings” protest where one local Democratic political candidate spoke out against “billion-dollar corporations like Oracle” and others “moving into our rural communities.”

“They’re exploiting them for all of their resources, and they are creating a surveillance state,” said Riley Rodriguez, a candidate for Texas state Senate District 28.

In Holly Ridge, Lousiana, the construction of the world’s largest data center has brought thousands of dump trucks and 18-wheelers driving through town on a daily basis, causing crashes to rise 600% and forcing a local school to shut down its playground due to safety concerns.

And people in communities across the US know the construction of massive data centers are only the beginning of their troubles, as electricity bills have surged this year in areas like northern Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio, which have a high concentration of the facilities.

The centers are also projected to use the same amount of water as 18.5 million homes normally, according to a letter signed by more than 200 environmental justice groups this week.

And in a survey of Pennsylvanians last week, Emerson College found 55% of respondents believed the expansion of AI will decrease the number of jobs available in their current industry. Sanders released an analysis in October showing that corporations including Amazon, Walmart, and UnitedHealth Group are already openly planning to slash jobs by shifting operations to AI.

In his video on Wednesday, Sanders applauded residents who have spoken out against the encroachment of Big Tech firms in their towns and cities.

“In community after community, Americans are fighting back against the data centers being built by some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world,” said Sanders. “They are opposing the destruction of their local environment, soaring electric bills, and the diversion of scarce water supplies.”

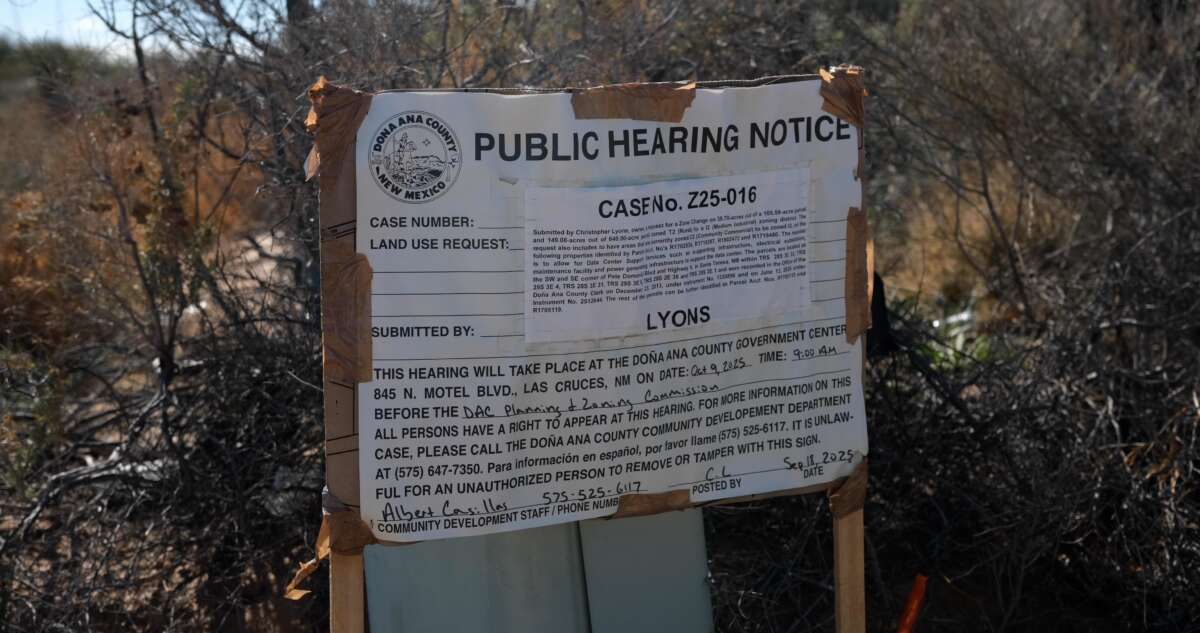

Secretive New Mexico Data Center Plan Races Forward Despite Community Pushback

To power the growing demand for AI, New Mexico is gearing up to build a data center with a city-sized carbon footprint.

By Dan Ross ,

At the very Southeastern tip of New Mexico bordering Texas and Mexico, a new artificial intelligence (AI) data center is gearing up to be a greenhouse gas and air pollution behemoth, an additional water user in a drought-afflicted region, and a sower of community discontent.

Project Jupiter is one of five sites in the $500 billion Stargate Project, a national pipeline of massive AI systems linked with OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank.

“Health is my biggest concern. I’m worried about the air pollution, the ozone, and the buzzing noise,” local resident José Saldaña Jr., 45, told Truthout. Saldaña has lived in Sunland Park, New Mexico, nearly his entire life, and he’s worried about Project Jupiter’s added environmental footprint in a pollution hotspot. Another big data center is going up in nearby El Paso, Texas. He lives less than two miles from a landfill that emits such an unpleasant smell, he can’t even hang his clothes out to dry.

“I’m just trying to stand up for my community,” Saldaña said of his opposition to the facility. But the project is racing ahead, and has already cleared one important hurdle: financing, including a massive tax break for the data center’s backers.

“Health is my biggest concern. I’m worried about the air pollution, the ozone, and the buzzing noise.”

Between September and October, the Doña Ana County Board of County Commissioners approved three funding ordinances, including the sale of industrial revenue bonds up to $165 billion.

With important permitting decisions still pending, work at the project site has already begun. Proponents tout all sorts of alleged benefits. This includes at least 750 well-paid new full-time positions and 50 part-time roles within three years of operations, with a priority for local hires. Instead of paying property and gross receipt taxes, the project will make incremental payments spread out over 30 years totalling $360 million — just a fraction of the bond monies.

Related Story

Data Centers Devour Electricity. Private Equity Is Buying Utilities to Cash In.

The seizure of public utilities for the sake of profit may lead to a disaster for consumers — and the planet. By Derek Seidman , Truthout November 11, 2025

Opponents of the project argue, however, that any benefits to the local economy are far outweighed by the impacts from potentially millions of tons of heat-trapping gas emissions annually from the plant’s proposed energy microgrid. This, when global warming is on track to increase by as much as 2.8 degrees Celsius over the century, blowing past Paris Agreement benchmarks set just 10 years ago.

And while Project Jupiter isn’t expected to be as thirsty as some of its fellow data centers, water advocates warn about any uptick of water usage in this drought-afflicted region, especially when New Mexico is projected to have 25 percent less surface and groundwater recharge by 2070 due to climate change.

“There’s so much secrecy and lack of information about the project.”

“There’s so much secrecy and lack of information about the project,” Norm Gaume told Truthout. Indeed, a lot of the negotiations around the project have occurred behind closed doors. Gaume is a retired state water manager and now president of the nonprofit New Mexico Water Advocates.

“What is certain is two things: Global warming is taking our renewable water away. And Project Jupiter intends to use the least efficient gas turbine generators,” said Gaume. “Their emissions are just over the top.”

Massive Energy Consumption

The recent, rampant proliferation of AI in everyday life has prompted the swift buildout of enormous facilities to house the machinery needed to crunch extraordinary amounts of data — a process that requires enormous amounts of energy. Just how much?

The Western Resource Advocates, a nonprofit fighting climate change and its impacts, recently published a report showing how seven of the eight largest utilities in the interior West forecast an increase in annual energy demand of about 4.5 percent per year, driven primarily by the growth of energy-sucking data centers. In comparison, their annual electricity sales grew by only about 1 percent per year between 2010 and 2023.

Seven of the eight largest utilities in the interior West forecast an increase in annual energy demand of about 4.5 percent per year, driven primarily by the growth of energy-sucking data centers.

This week, over 200 groups from all over the country jointly signed a letter to Congress urging for a moratorium on new data centers until safeguards are in place to protect communities, families, and the environment from the “economic, environmental, climate and water security” threats they pose.

Project Jupiter is set to be powered by two natural gas-fueled microgrids. But air quality permits recently filed with the New Mexico Environment Department show the project could reportedly emit as much as 14 million tons of carbon dioxide a year, according to Source NM. How much is that? The entirety of Los Angeles, the country’s second-largest city by population, emitted just over 26 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2022.

Under state law, qualified microgrids won’t be required to transition to a 100 percent renewable energy system for another 20 years, Deborah Kapiloff, a clean energy policy adviser with the nonprofit Western Resource Advocates, told Truthout. “So hypothetically, up until January 1, 2045, [Project Jupiter’s operators] could run their gas plants at full capacity. There are no interim guidelines. There’s no off-ramp,” she added.

Furthermore, the region is already classed as a marginal “non-attainment” area, meaning it fails in part to meet federal air quality standards for things like ozone and fine particulate matter levels. And local residents are concerned about the addition in the area of noxious air pollutants — including PM2.5, one of the most dangerous such pollutants linked to serious health issues like cardiovascular disease — from the gas powered microgrids.

The project could reportedly emit as much as 14 million tons of carbon dioxide a year.

“Technically, the EPA could decline these air quality permits because we have such bad air quality already,” documentary filmmaker Annie Ersinghaus told Truthout. She lives in the adjacent city of Las Cruces, New Mexico, and is skeptical the Environmental Protection Agency will intervene. “It very much feels like David and Goliath.”

Then there’s the water component.

Water Usage

According to online materials, the project’s data centers will require a total one-time fill volume of approximately 2.5 million gallons (which is the equivalent to the annual water usage of just under 25 households). Once operational, Project Jupiter’s data centers will use an average of 20,000 gallons per day (which is equivalent in daily usage of about 67 average households).

This doesn’t appear to be a lot of water — some data centers can use millions of gallons daily

Project Jupiter’s developers boast an efficient closed-loop cooling system. But Kacey Hovden, a staff attorney with the nonprofit New Mexico Environmental Law Center, warned Truthout that this type of cooling system hasn’t yet been used at a fully operational facility, and therefore, it’s currently unknown whether those projected numbers are realistic.

In the background lurks a rapidly warming world marked by huge declines in global freshwater reserves. Arid New Mexico is at the heart of this problem.

A comprehensive analysis of the impacts from climate change on water resources in New Mexico paint a picture over the next 50 years of temperatures rising as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit across the state, and with it, reduced water availability from lighter snowpacks, lower soil moisture levels, greater frequency and intensity of wildfires, and much more aggressive competition for scarce water resources.

Gaume told Truthout the state needs to take every step possible to curtail water usage rather than add to its needs. “This is a pig in a poke,” Gaume said about Project Jupiter. “We’re living in a fantasy world where people aren’t really paying attention to water.”

The project’s potential impacts on the community’s drinking water supplies is further complicated by the fact that both will share a water supplier, at least for a while — the Camino Real Regional Utility Authority, which has long been marred by water quality issues, including serving water containing elevated arsenic levels to its customers. An Environmental Working Group assessment of the utility’s compliance records finds it in “serious violation” of federal health-based drinking water standards.

The utility’s problems have gotten so bad that the Doña Ana Board of County Commissioners voted in May to approve the termination of the joint powers agreement that created the utility. Exactly what will replace it is currently unclear.

Project Jupiter will supposedly contribute $50 million to expand water and wastewater infrastructure. But it’s also unclear exactly how those funds will be used — whether just for the data center or for the community as well — and when. Hovden described this promised investment as nebulous. “I would say that’s probably the best way to describe everything around this project,” she said.

Multiple messages to BorderPlex Digital Assets — one of two project developers alongside STACK Infrastructure — went unanswered.

Then comes the issue of groundwater, the region’s primary water source. Once again, there’s very little known about the sustainable health of the region’s groundwater tables.

“The horse is way out ahead of the cart in this situation, where we don’t really know a lot of the details of how this project might impact New Mexico, especially its water,” Stacy Timmons, associate director of hydrogeology at the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, told Truthout. She’s currently involved in a state project to better understand the status of New Mexico’s groundwater resources.

Community Pushback

Caught unawares by the speed with which this project was announced and is moving forward, community pushback is beginning to coalesce. At the end of October, the New Mexico Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit on behalf of José Saldaña and another local resident, Vivian Fuller, against the Doña Ana County Board of County Commissioners, arguing that they had unlawfully approved the three funding ordinances.

Ersinghaus is one of a group of local residents behind Jupiter Watch. They turn up at the construction site to monitor and track its progress, to make sure permits are in order (they often aren’t, she said), and to bring some “accountability” to the project. A large protest is scheduled for early next year, to coincide with the air quality permit decisions.

“Jupiter Watch came along very spontaneously,” said Ersinghaus, about the impetus behind the group in light of the hastily fast-tracked project. “Our commissioners voted for this [bar one], and we want them to feel ashamed.”

Saldaña said that he’d like regulators and politicians to halt the project and move it elsewhere. If they don’t, he speculated that he might pack up and move from the region he’s called home since 1980.

“In the worst case scenario, I’ll tell my mom, ‘Let’s move, let’s get the hell out of here.’ But I don’t want to move,” said Saldaña. His mother lives next door to him and he has many relatives in the area. “It’s sad. Very sad.”

Truthout’s December fundraiser is our most important of the year and will determine the scale of work we will be able to do in 2026. Please support us with a tax-deductible donation today.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

The AI Boom: Hype, Power and the Coming Reckoning

Photo by Luke Jones

It is safe to say that since OpenAI first released ChatGPT in October 2022, AI has been the most widely covered and discussed topic in the U.S. By January 2023, ChatGPT had become the fastest-growing consumer software app in history, gaining over 100 million users in its first two months. Currently, its website has over 800 million weekly users. Since ChatGPT’s emergence, the question of AI and its potential and pitfalls has dominated discourse.

Indeed, daily, one is bound to run into numerous headlines in both the business and tech press. Just to take a quick example, on September 18th, Time magazine put forward two stories. One was titled ‘AI is Learning to Predict the Future- and Beating Humans at It’ (that story dealt with an AI system finishing in the top 10 of the Summer Cup, a forecasting contest); the other read ‘AI is Scheming and Stopping It Won’t Be Easy, OpenAI Study Finds’ (this one touched on the fact that all of today’s best AI systems- Google’s Gemini, Anthropic’s Claude Opus, can engage in scheming- meaning they can pretend to do what their human developers want, while actually pursuing different objectives).

One can do this all day. In August, Wired featured a headline, ‘Nuclear Experts Say Mixing AI and Nuclear Weapons is Inevitable.’ More recently, Wired featured a story that Anthropic recently partnered with the U.S. government to ensure that Claude wouldn’t spill nuclear secrets and help another entity build a nuke. Explicit in this is the geopolitical sphere. This past July, the New York Times Business page declared ‘The Global AI Divide’ that has wealthier regions building out robust data centers while poorer regions are left behind. And there have been U.S. efforts to freeze China out of the cutting-edge chip market, not to mention the apprehension about open-source models from Chinese companies such as DeepSeek. Then there have been countless stories featuring the coming revolutionary effect AI will have on everything from drug development to medical diagnosis (‘a doctor in every pocket’) to food production to films to love lives to weather forecasting to, well, everything.

Go a bit deeper and, depending on who one talks to, AI will usher everything from a global dystopia where almost nobody will be able to earn a living since AI and robots will make people unnecessary to employers to global socialism- since we can’t allow the former scenario to come to pass, we’ll need to usher in the latter and AI can be a better agent for a planned economy than human bureaucrats. In that case, AI would indeed have a major role in ushering in universal abundance and perhaps very long lifespans.

There is also the infamous idea, featured in The Terminator movies, that superintelligent AI will replace us mere Homo Sapiens, for one reason or another, with higher forms of life. Not surprising perhaps one can find some who are actively cheering for that prospect.

For a harrowing primer on that, there is Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nick Scoares’ book If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us. The main point here is that no one knows exactly how AI works and therefore no one can completely predict its perceived interest. Known as the alignment problem, we can’t be sure superintelligence will have its interests completely aligned with ours. Yudkowski and Scoares write:

“The most fundamental fact about current AIs is that they

are grown, not crafted. It is not like how other software gets

made- indeed it is closer to how a human gets made, at least in

important ways. Namely, engineers understand the process that

results in an AI, but do not much understand what goes on inside

the AI minds they manage to create.”

It may not be that an AI system comes to want to annihilate us out of maliciousness, either. The authors cite the example of building a skyscraper on a patch of land that has an ant hill. We’re not trying to deliberately kill ants; we’re just trying to build a skyscraper and preserving the ants in that location isn’t important enough to be considered. Such could be our relationship with superintelligence and, as the authors note, such intelligence once built can’t be simply unplugged once it exists.

None of that appears to be having any effect on capital pouring into AI, but on that note a different narrative has crept up in the discourse. In August, the Financial Times asked, ‘Is AI hitting a wall.’ Given the general disappointment with OpenAI’s GPT-5, FT wrote: ‘Following hundreds of billions of dollars of investment in generative AI and the computing infrastructure that powers it, the question suddenly sweeping Silicon Valley is: what if this is as good as it gets?’ The piece then added the magic word: bubble.

It was right around that time when an MIT study came out showing that 95 percent of the generative AI implementations in enterprises have had zero return on their investment (that investment equals $30 to $40 billion). A month earlier, the think tank Model Evaluation & Threat put out a study involving a randomly selected group of experienced software developers to perform coding tasks with or without AI tools. Giving that coding is a task that current AI models are supposed to have mastered, all involved in the study expected productivity gains for those using the AI. Instead, the study found that those in the AI group completed their tasks 20 percent slower than those working without it. A McKinsey & Company report from March found that 71 percent of companies reported using generative AI, and more than 80 percent of them reported the AI had no ‘tangible impact’ on earnings.

Amara’s Law, named for American futurist Roy Amara, states that we tend to overstate the effect of technology in the short term and underestimate the effect in the long run. The idea being that there is a period of time between the development of new technologies and enterprises adjusting their operations to incorporate their use.

Economist Eric Brynjolsson, co-author of The Second Machine Age and Race Against the Machine, posits that every new technology experiences a ‘productivity J-curve’, meaning at first, enterprises struggle to deploy it, causing productivity to fall. Eventually, when they learn how to integrate it, productivity booms. Indeed, it took decades for technologies such as tractors and computers to have a significant impact on productivity. Even electricity itself, which became available in 1880s, didn’t begin to produce big productivity gains until the 1910s in Henry Ford’s factories.

Just to throw around some numbers, this year, large tech firms in the U.S. will spend nearly $400 billion on AI infrastructure. By the end of 2028, analysts reckon the amount spent on data centers worldwide will be more than $3 trillion. According to recent data from Pitchbook, AI startups received 53 percent of all global venture capital dollars invested- in the U.S., that percentage jumps to 64 percent.

With other sectors of the economy showing signs of sluggishness, likely in part due to Trump’s tariffs, for instance, roughly 78,000 manufacturing jobs have been lost this year, AI is holding the fort. In a column for the Financial Times titled ‘America is now one big bet on AI’, Ruchir Sharma writes that AI companies account for 80 percent of the gains in U.S. stocks so far in 2025. In fact, more than a fifth of the entire S&P 500 market cap is now just three companies- Microsoft, Apple, and Nvidia- two of which are largely bets on AI. Nvidia recently became the first company to reach a $5 trillion market cap, while Microsoft recently hit $4 trillion.

Another word from past bubbles that has been creeping into the ether is debt. On September 30th, the Wall Street Journal wrote: ‘In the initial years of the artificial-intelligence boom, comparisons to the dot-com bubble didn’t make much sense. Three years in, growing levels of debt are making them ring a little truer…a crop of highly leveraged companies is ushering an era that could change the complexion of the boom.’

Oracle, for example, which pledged a $300 billion investment in AI infrastructure with OpenAI now owes over $111 billion in debt. Quick FactSet reports that interest-bearing debt of the 1300 largest tech companies in the world has quadrupled over the past decade and now stands at roughly $1.35 trillion. According to analysts at Morgan Stanley, debt used to fund data centers could exceed $1 trillion by 2028.

Much of this capital is flowing in something of a circle. In other words, one company pays money to another company as part of a transaction, then the other company turns around and buys the first company’s products and services (and without the first transaction, that other company may not be able to make the purchase). Nvidia agrees to invest $100 billion in OpenAI to fund data centers and Open AI commits to filling said centers with purchased Nvidia chips; Oracle has a $300 billion deal with OpenAI for a data center buildout and is spending billions on Nvidia chips; Nvidia is planning on investing $2 billion in Elon Musk’s xAI and has agreed to buy $6.3 billion worth of cloud serving from CoreWeave, the leading independent operator of AI data centers in the U.S.; Meta agreed to buy $14.3 billion from CoreWeave in September (CoreWeave has told financial analysts for every billion in computing power it plans to sell it must borrow $2.85 billion); CoreWeave put $350 million in OpenAI…etc.

Needless to say, companies like OpenAI and Anthropic are nowhere near profitable. By one estimate, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Tesla will by the end of the year have spent $560 billion on AI-related capital expenditures since the beginning of 2024 and brought back just $35 billion in AI-related revenue. It is tempting to say that AI is too big to fail. But what is the damage if the bubble does pop? In an essay titled What Kind of Bubble is AI, tech writer Corey Doctorow writes ‘Tech bubbles come in two varieties: The ones that leave something behind, and the ones that leave nothing behind. Sometimes, it can be hard to guess what kind of bubble you’re living through until it pops and you find out the hard way.’ Past manias, such as the 19th-century British railroad bubble at least left useful infrastructure. It is hard to see what other uses there can be for all these data centers.

And this leads to another narrative that’s floating in the ether. In their book The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want, Emily Benner and Alex Hanna argue that we’re essentially being sold a bill of goods. What is being labeled ‘AI’ is in fact a marketing term for a bundle of different technologies. The Large-Language Models (LLMs) so in vogue are just ‘synthetic text-extruding machines’ that ‘out and out plagiarize their inputs’ and site nonexistent sources. And plagiarism seems like quite a fair charge. It is true that all art and technology build on what came before, but Van Gogh didn’t copy and paste the Japanese prints that influenced him into his paintings. LLMs aren’t adding any new inputs, they just directly synthesize the creative inputs of others. Much of the media, under the thrall of tech CEOs and boosters, are reporting every small success but nothing about AI’s many failures. In this case, both the boosters and the doomers miss the point. AI may not take your job away, but it may well make it shittier. Making some people redundant, allowing greater exploitation of others, AI is simply another move for greater profits squeezed out of the masses.

Tech boosters and corporate henchmen will often shout ‘Luddite’ at this kind of talk. This actually ends up not making the intended point. If the contemporary idea of a Luddite is someone slamming their new gadget against a wall in frustration or proudly grinding their own coffee beans while jamming to a vinyl record, the original Luddites should not be understood as an anti-tech movement, but as a social protest rooted in early nineteenth-century England. The machines they smashed in protest, the stocking frame, were not new pieces of technology. By the time the Luddites burst onto the scene in 1811, the stocking frame had existed for more than two centuries. In fact, the Luddites can’t even claim originality since machine-breaking had a long history in English protests.

The Luddites’ problem was not with technology per se, but how it was applied- the way it was used to create unemployment, impoverish skilled workers, increase production while stagnating wages. One can see the shadow of this in such actions as the 2023 strike by the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild against the Hollywood studios. It seems a safe bet we’ll be seeing more such resistance in the coming years. Journalists from the news site Politico recently won an arbitration ruling regarding AI against the company. The arbitrator ruled that Politico officially violated the collective bargaining agreement by failing to provide notice, human oversight, or an opportunity for the workers to bargain over the use of AI in the newsroom.

Finally, one shouldn’t overlook the anti-democratic ethos behind AI boosting. Offshoring problem-solving to AI, even if it can be done, means just concentrating power into the hands of a select few who own the AI. That appears to be precisely the point: no more messy democratic planning and consensus building. For example, take former Alphabet CEO Eric Schmitt regarding climate change and AI: ‘My own opinion is that we’re not going to hit the climate goals anyway because we are not organized to do it and, yes, the needs in this area [AI] will be a problem. But I’d rather bet on AI solving the problem than constraining it.’ OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has been proclaiming that we need AI to solve the big problems facing us, such as global warming to colonizing space.

Data centers are the reason the big tech companies have openly blown past their previously stated green targets, not to mention a key factor in increased electricity use in the U.S. (after being flat for decades) and rising electric bills.

But AI won’t relieve us from the hard work of democratic politics and there is no reason why AI development should be exempt from such work. Yudkowsky and Scoares call for full-on public mobilization to keep the worst from happening. Even if the ultimate doomer vision doesn’t convince many, there is still plenty to discuss. Few would dispute the positive, specific contribution AI can make, like helping to solve part of the protein-folding problem (that AlphaFold, developed by Alphabet subsidiary DeepMind, in 2023) and assisting in developing needed antibiotics and other medical advances like improved diagnosis. But anything can be subject to debate and regulation, even public ownership. Demands for transparency in how systems are designed and for whose benefit should be spewing from elected officials. And there are those CO2 emissions to consider.

Corey Doctorow recently called AI ‘the asbestos we are shoveling into the walls of our society and our descendants will be digging it out for generations…AI isn’t going to wake up, become superintelligent and turn you into paperclips- but rich people with AI investor psychosis are almost certainly going to make you much, much poorer.’ Obviously, only democratic engagement and collective responsibility could avoid that bleak vision. Such calls always seem like long shots but, really, is there anything else?

No comments:

Post a Comment