The sources of the Ukraine conflict: A reply to Chris Slee

Why did Russian military forces in February 2022 enter Ukrainian territory in massive numbers and along a broad front? Chris Slee sets out to supply an answer in his article, “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: Defensive response or imperialist aggression?”, published on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

Slee’s article takes the form of a reply to an earlier LINKS article by Dave Holmes, “What’s really at stake in Ukraine?” While Slee is mainly concerned to rebut specific points that Holmes raises, he also expresses, or strongly implies, a range of broader positions. These can be summarised as follows:

- Today’s Russia is an imperialist power, as evidenced by its military strength.

- The source of the antagonism between the US and Russia is Russian president Vladimir Putin’s ambition for Russia to once again become a great power, able to rival the US. Russia is among the major sources of violence in the world today, even if not on the scale of the US.

- Putin’s decision in 2022 to expand the existing Donbas war was unjustified. Moreover, the move turned out to be counterproductive, amounting to “a gift to NATO”.

- Socialists should condemn Russia’s invasion and campaign in solidarity with anti-war forces in Russia. But with a Ukrainian military victory scarcely in prospect, we should be calling for a ceasefire. If Russia does not agree to a ceasefire, we should call for Ukraine to receive additional military aid.

These propositions will now be examined in turn.

A non-imperialist imperialism?

Slee has no doubt that today’s Russia is an imperialist country. Here are the terms in which he describes the eight-year war that followed the 2014 uprising in Ukraine’s Donbas region and Russia’s “special military operation” from February 2022:

The war in Donbas became a conflict between a Ukrainian government subservient to Western imperialism and reactionary puppet regimes in eastern Ukraine subservient to Russia. The conflict increasingly resembled an inter-imperialist proxy war.

Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed the situation, converting it into a war of aggression by an imperialist power (Russia) against a semi-colonial country (Ukraine).

But is the possession of a large military strength, and its use outside the national territory, enough to brand a country as imperialist? There are various reasons why countries may decide to build up their military apparatus. One reason is to intimidate, and given the excuse, to attack other states; another is to enable defence against a well-founded fear of such aggression.

Slee accepts that the US is “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”, and does not contest that Russia is among the main targets of US threats. It would seem to follow that Russia’s possession of one of the world’s larger “military strengths” does not, in itself, settle the question of whether the country is imperialist.

For bourgeois media commentators, “imperialism” generally equates simply to the use of military aggression to seize the territory of a foreign state. Marxism delves much deeper, looking to the material (and above all, economic) roots of imperialism in the modern industrial era. For Marxists, imperialism may express itself in armed aggression, but its essence lies in the contradictions of capitalism during its advanced stage.

As analysed by Lenin early in the last century, imperialism is a characteristic of the richest and most developed capitalist countries. Capitalism at this stage of its evolution runs regularly into an intractable dilemma, in which a huge build-up of capital is accompanied by a strong tendency for the rates of profit on that capital to fall. This places enormous pressure on national capitalist classes to restore their fortunes by investing in less developed regions and countries where profit rates are higher. There is a corresponding pressure to back up this expansion with military force.

As a long-time Marxist, Slee is well aware of these points. To make his case further, he pursues two main lines of argument. One of these rests on a passage from Lenin’s writings of 1916:

The last third of the nineteenth century saw the transition to the new, imperialist era. Finance capital not of one, but of several, though very few, Great Powers enjoys a monopoly. (In Japan and Russia the monopoly of military power, vast territories, or special facilities for robbing minority nationalities, China, etc, partly supplements, partly takes the place of, the monopoly of modern, up-to-date finance capital.)

Lenin made these remarks at a time when the imperialist system was much less mature than it is today, and still featured a variety of strange contradictions that have long since been resolved. One of these was the contradiction — of which Lenin was thoroughly conscious — between the fact that the Russian empire of his day remained a primitive and dependent state, at the same time as it was a ranking military power, able to keep large non-Russian populations in subjection and to throw millions of soldiers into its wars.

Russia, Lenin recognised, had a presence in the broad picture of imperialist relations in the early twentieth century. But in what capacity did it figure there? To view a still overwhelmingly pre-industrial country as embodying modern industrial imperialism, the “highest stage of capitalism”, was plainly absurd.

In his writings, Lenin never fully untangled this conundrum. But he left us a definite pointer to his views. In articles in 1915 and 1916 he described the Russian imperialism of his time as “ feudal” and as “crude, medieval, economically backward”. Clearly, he did not include it in the same category with the modern imperialism of the advanced Western countries.

Instead, the Russian empire was a relic of an earlier, pre-industrial imperialism, based not on finance capital and advanced productive methods, but on peasant rents, handicraft production and merchants’ profits. For Lenin, it may be said, the Russian empire despite its military power belonged in a historical category with such empires as that of the Ottomans.

Russia’s “feudal, medieval” imperialism perished in 1917. To characterise the country today using the tsarist regime as a historical reference is far-fetched. The return of capitalism to Russia from 1991 saw the Russian Federation emerge as a typical “upper tier” country of the Global South; part of the “semi-periphery” of world capitalism along with countries such as Brazil, Mexico, or Türkiye.

While Russia in 1991 inherited an industrial economy from the Soviet Union, the level of its technology in all but a few sectors was decidedly backward. There was no way the new post-Soviet state could share significantly in the flood of poor-country wealth that accrued to the countries of the imperialist “centre” due to their monopoly over the most advanced productive methods.

Instead, Russia over the following decades led a straitened existence as a low-wage, capital-poor exporter mainly of raw materials and semi-finished products. While Russian capitalists have profited from exploiting the labour and resources of their country’s national minorities, this in no way distinguishes them from the capitalists of Indonesia, Nigeria, or many other multi-ethnic, clearly non-imperialist states.

Slee’s second line of analysis is more involved, and seemingly scientific, but the results it yields are no more convincing. Russia, he observes, is far from being the poorest country in the world:

Russia holds an intermediate position in terms of GDP. It is not at the top of the list, but nor is it near the bottom. Russia was 47th out of 191 countries in GDP (PPP) per capita in 2023. This means its GDP (PPP) per capita was higher than more than 70% of countries.

Together with Russia’s large military forces, Slee implies, this middling position can be taken as evidence that the country should be regarded as imperialist. But the fact that Russia is above the mid-point of the world’s countries in the per capita rankings for GDP at Purchasing Price Parity (PPP) establishes nothing — except, perhaps, to show that semi-developed countries are exploited by imperialism along with the most indigent.

It may be that by citing this index, Slee hopes to imply a steady linear progression of countries from poorest to richest, with the suggestion that the less impoverished countries of the Global South may be — sort of — imperialist. But this is misleading, since other statistics reveal a sharply different picture.

GDP (PPP) per capita measures the cost in “international dollars” of a standard basket of goods in a particular country, and allows a comparison of average living standards in different parts of the world. In 2024, Russia’s per capita GDP (PPP) was not much more than half that of the US. GDP (PPP), however, is not a good index for assessing whether a country might qualify as imperialist.

For this purpose, a far more useful measure is nominal GDP, which takes account of factors such as a country’s international balance of trade and its currency exchange rate. Nominal GDP gives an idea of a country’s strength in international financial and commercial dealings — which is a great deal of what imperialism is about.

In 2024, nominal US GDP per capita was US$85,810, while that of Russia was $14,889 — barely one-sixth as much. If we turn our attention to wealth, as distinct from income, the disparity is still more glaring. According to the UBS Global Wealth Databook for 2023, average wealth per adult in Russia the previous year was $39,514 — markedly less than in Mexico, and about one-fourteenth of the corresponding figure for the US.

Or, we can consider financial wealth per adult. This is an especially revealing figure, since it provides a proxy for the relative dimensions in various countries of finance capital — the complex of financial and industrial might that Lenin saw as lying at the heart of imperialism. As listed by UBS, financial wealth per adult in Russia at the beginning of 2022 was again much less than in Mexico — and about one thirty-fourth of the figure in the US.

As these statistics suggest, there is no regular, linear progression of the world’s countries from poor to rich, and few of the less-favoured nations have made it far up the scale. Entry to the “gated community” of the world’s rich states is effectively locked and barred; the list of genuinely wealthy countries, which apart from mini-states number about 20 in all, has barely altered since Lenin’s time.

The category of “middle-income” nations is also strikingly tiny. Again apart from mini-states, fewer than 20 of the world’s 195 or so countries inhabit the wide developmental gulf that exists between distinct poverty and decided wealth. Most of these economically “intermediate” countries, moreover, are small. The lack of a strong cohort of middle-income states reflects directly what imperialism is and how it operates, stripping wealth from the poor, channeling it to the rich, and keeping most of humanity in underdevelopment.

The world flows of value that originally created, and have maintained, this lopsided global distribution of wealth operate through mechanisms that include remitted profits, interest payments, rents, and unequal trading exchange. These net flows, it may be argued, provide the best single pointer to which countries should be identified as imperialist, and which not. Improved statistics now allow these flows to be calculated with some precision.

Recent studies by three separate teams of researchers conclude that over the past few decades, the biggest loser countries from the imperialist-dictated mechanisms of world trade and finance have included Russia. Combining the findings of several of these studies reveals that between 2010–22, the losses to Russia almost certainly amounted to well over 4% of its GDP.

Taken together, the data for nominal GDP, wealth per capita, gross financial wealth per adult, and net international flows of value show decisively that Russia is not among the perpetrators of imperialism, but one of its prime victims.

If we accept that present-day Russia is not an imperialist state, what does this indicate for Slee’s suggestion that Russia’s actions in Ukraine amount to a case of imperial aggression?

Imperialist states, if we read Lenin correctly, are marked by a surfeit of underused capital, seeking employment at the rates of profit its owners think they deserve. But the data cited above show that, compared to undoubted imperialist countries, Russia is strikingly capital-poor. Russian industry and infrastructure, the military sector aside, suffer from a severe lack of investment.

Meanwhile, the country is home to legendary natural resources that, in normal times, command high prices on world markets. To the extent that Russian entrepreneurs have capital to invest, they have the opportunity to draw very agreeable rates of profit at home, without the obloquy and vast expense of invading foreign countries.

The charge that Russia launched its “special military operation” in Ukraine from an imperialist drive to territorial expansion is therefore absurd. If we discard (as we should) the “crazed dictator” narratives current in the West, that leaves us compelled to accept that the reason for Moscow’s “special military operation” is exactly what the Russians say it is: a defensive response to determined, persistent Western menaces.

Great power ambitions?

Discussion of the specific causes behind Russia’s Ukraine intervention, however, must wait. First, we should examine what Slee says about the general sources and conduct of Russia’s foreign policy.

In the 1990s, Slee states,

... the US supported the Boris Yeltsin regime ... At the time, the US trusted Russia more than Ukraine. Hence the US insisted that nuclear weapons on Ukrainian soil be transferred to Russia... However, the US did not want Russia to become strong enough to be an imperialist rival. Putin, on the other hand, wants Russia to once again become a great power. This has led to a rise in conflict between the US and Russia.

The US antagonism to Russia, it should be noted, has causes that go much deeper than any presumed power-dreams of the Russian president. Meanwhile, we may recall that while Russia did not suffer China’s “century of humiliation” at the hands of imperialism, it certainly endured a decade of plunder by the West.

Between 1990–98, World Bank figures reveal Russia’s real GDP fell by more than 60% as Western economic advisors installed in the Kremlin scripted “shock therapy” policies, and as imperialist interests joined with the rising local oligarchy in stripping the country of wealth. With that experience behind them, Russians have real cause to want to become, if not a “great power” in the imperialist sense, then certainly a country treated with caution and respect.

This “framing” of the origins of the Ukraine conflict is essentially absent from Slee’s article. Instead, Slee makes considerable play with the argument that, like the US, “Putin’s Russia is also a major source of violence”.

This is a curious judgement if we consider the respective abilities of the US and Russia to project their armed power outside their borders. The World Beyond War site puts the number of US military bases on foreign territory in 2025 at 877, in 95 countries. According to the same source, Russia has 29, the great majority of them inherited from and located in countries of the former Soviet Union. Several more Russian bases are in Syria. Moves by Russia to secure a naval station on Sudan’s Red Sea coast appear to have stalled.

This pattern does not suggest the pursuit by Russia of world hegemony, but rather, a focus on its own security. All of Russia’s military bases, actual or mooted, outside of the former Soviet Union are in the Middle East — a strategically sensitive area of Russia’s “near abroad”. Moscow’s foreign policy-makers have historically sought good relations with Middle Eastern governments. For many years this involved economic and military cooperation with the government of Bashir al-Assad in Syria.

Assad’s government was under attack from Islamist insurgents for more than a decade. During part of this time, the military assistance provided by Russia included strikes by its aircraft on insurgent base areas. In December 2024 the insurgents overthrew Assad’s regime, and the status of Russia’s bases in Syria became precarious.

Throughout much of 2025 Syria’s new rulers showed a relatively accommodating attitude to Russia’s presence, perhaps regarding it as a counterweight to the (far greater) combined footprint of Israeli and US forces on Syrian territory. By November 2025, however, the US was welcoming the new Syrian president (and founder of al-Qaida’s Syrian affiliate) Ahmed al-Sharaa to the White House, and Sharaa was reportedly expressing a wish to be “a great ally to the United States of America”.

The complex, shifting picture presented by these developments finds little reflection in Slee’s article, which limits itself to stating: “Russian aircraft bombed rebel-held areas in Syria, causing widespread death and destruction in a failed attempt to prop up the Bashar al-Assad regime”.

Russia’s foreign policy-makers have a reputation for being highly skilled, for understanding the limited nature of their options, and for playing a generally weak hand with impressive finesse. The country’s foreign policy moves, especially when compared to those of Western powers, such as the US, Britain and France, have normally been distinguished by caution and restraint, often despite high levels of provocation.

Nevertheless, Russia’s foreign policy is that of an oligarchic capitalist state, and its purpose is to defend the interests of that state, not the rights of the world’s oppressed. Unsurprisingly, the practical implementation of this (capitalist) foreign policy includes a component of “covert operations” — at times, in an apparent effort to preserve “deniability”, mounted at arm’s length from official Russian institutions.

Slee observes: “Russian mercenaries employed by the Wagner Private Military Company have been involved in wars in a number of African countries”. The Wagner PMC (or Wagner Group) is, or was, an opaque network of private shell firms with its main base in Russia. Early in 2023 it was described by a British source as “a web of dark money that spreads through dozens of countries”.

At its height in the early 2020s, the group functioned in as many as ten African countries, largely in the Sahel region but also, and notably, in the Central African Republic. One report speaks of it employing as many as 5000 operatives, largely veterans of the Russian armed services. The group appears to have been favoured by the African governments concerned because of its military effectiveness, its expertise in training local troops, and because it was free of “the political constraints of Western forces”.

There is no doubt that the Wagner Group benefited from having contacts at top levels of the Russian state. In a general way, it can be regarded as having served Russian goals in Africa. It was, in effect, a “public-private partnership” between the Kremlin authorities and Russian business interests.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to identify the Wagner Group closely with official Moscow. The above-cited British source stresses that the group was never subject to the GRU (Russian military intelligence), and that its relations with the Russian defence department were “fractious”. The Wagner Group evidently funded its African operations largely through private business operations in the countries involved, with the dealings believed to have included illegal mining and forestry, illicit trade in gold and gemstones, and money-laundering.

The history of the Wagner Group’s spectacular falling-out with the Putin administration in mid-2023, involving a wholesale mutiny by its forces in the Donbas, is well known. From that point, the Russian authorities clearly decided that military free-lancers gave more trouble than they yielded benefits. July 2023 saw the founding of the questionably-named Africa Corps, into which many of the Wagner operatives in Africa were folded. In late 2024, Danish researcher Karen Philippa Larsen described the Wagner Group as having been “almost completely dismantled”.

The Africa Corps is clearly much smaller than its Wagner predecessor, with a British Ministry of Defence source in 2024 suggesting a figure of 2000 regular soldiers and officers. A report published in September 2025 notes a “focus on training of local military and law enforcement”, while describing the corps as “tethered closely to the [Russian] military chain of command”, and characterising its operations as “low investment, low risk, directed by the Russian government, and embedded in broader political efforts”.

For the Russian state, the Africa Corps serves the military function of aiding the defeat of irregular military forces likely to threaten friendly governments, while undermining the influence of the region’s former imperial (mainly French) overlords. In a broader sense, the corps’ operations correspond to Moscow’s general foreign policy objectives in the Global South — which stress the need to provide backing to governments that are likely to offer Moscow support in international bodies, and that are prepared to countenance trading exchanges.

A defensive response?

Slee presents his next major argument as follows:

Even if it were true that Russian President Vladimir Putin was “worried about NATO’s intentions”, that still would not justify the invasion. Pre-emptive war was not the only option. Moreover, it was counterproductive ... The invasion was a gift to NATO.

It would be difficult to argue that Russia at the beginning of 2022 did not face a serious and mounting military threat from the NATO countries, and at least explicitly, Slee does not deny this. But before we try to characterise the logic, or otherwise, of Russian responses at this time, the circumstances leading up to these actions need to be sketched out in more detail.

Within a few years of US Secretary of State James Baker providing a guarantee to Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990 that NATO would not expand eastward, plans were in train for the alliance to do precisely this. With its economy disintegrating and its armed forces in disarray, Russia in the 1990s under Yeltsin was treated contemptuously by the NATO powers as a defeated rival, in no fit state to resist Western impositions. In March 1999, while Yeltsin was still in power, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic were added to the NATO camp. By 2020 a further eleven countries joined.

NATO’s expansion toward Russia’s borders was accompanied by other threatening moves. In 2002 the US withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. In April 2008, at a summit meeting in Bucharest, the NATO countries ignored blunt Russian warnings and resolved that Ukraine and Georgia would be admitted to the bloc. In 2019 the first Trump administration withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. This meant that if Ukraine joined the Western alliance, the way would be open for the stationing of US nuclear missiles a few minutes’ flight time from Moscow.

Meanwhile, the major NATO powers by 2020 had helped to finance, equip and train to Western standards a Ukrainian military machine whose personnel size was similar to that of France, and larger than that of Germany. Regular, large-scale NATO military exercises were held on Ukrainian territory.

For Putin and many other Russians to be “worried about NATO’s intentions” was entirely reasonable. Another element in the thinking of Russian leaders at the beginning of 2022 was a conviction that no promise Western leaders gave, and no agreement they signed, could be regarded as remotely trustworthy. Apart from the expansion of NATO and the US repudiation of nuclear arms treaties, the Kremlin chiefs by this time had the experience of the eight-year refusal by the Western powers to insist that their Ukrainian protégés enact the Minsk agreements, that would have seen the Donbas remain Ukrainian territory.

The only deals that the NATO powers might conceivably be forced to respect, Russian leaders may well have decided, were those backed by facts on the ground. British historian Geoffrey Roberts argues that the “special military operation” in Ukraine was viewed by Putin as a preventive move:

The longer war was delayed ... [Putin] argued in February 2022, the greater would be the danger and the more costly a future conflict between Russia, Ukraine, and the West. Better to go to war now, before NATO’s Ukrainian bridgehead on Russia’s borders became an imminent rather than a potential existential threat.

Nevertheless, the Russian government as late as February 2022 persisted with strenuous diplomatic efforts to find a non-military solution to the crisis. Roberts suggests the final trigger for sending Russian forces across the Ukrainian border

... might have been President Zelensky’s defiant speech to the Munich Security Conference on 19 February, in which he threatened Ukrainian re-acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Does all this mean that the “special military operation” was justified? To answer this, we need to reflect that a capitalist regime is not the only form of government that can exist. There are also workers’ governments, based on the power of the mobilised popular masses. Such governments have foreign policy options that capitalist regimes do not.

For example, a workers’ government will rest upon and consciously develop a degree of popular democracy and workers’ power that the mass of people in other countries, as well, find attractive and inspiring. Through such political strategies, a workers’ government can gravely undermine the war preparations of imperialist adversaries. If applied consistently, over an extended period, this approach of fostering international workers’ solidarity can make the imperialists’ drive to war impossible.

In the case of today’s Russia, such calculations are totally hypothetical, ruled out by the class realities of the modern Russian state. Putin does not run a workers’ government. But simply to raise the above possibility gives the lie to the claim that the Russian president had no choice except to launch a broad military incursion into Ukraine. No law of nature forces him to rule in the interests of the Russian oligarchs. He had alternatives.

We do not, of course, wage our struggles in the world of hypotheses, but in the world as it actually exists. In this real world, an astonishing array of imperialist forces have ganged up on a non-imperialist country: Russia. The imperialists began their drive to war on Russia back in the 1990s, as they expanded NATO into Eastern Europe.

Moreover, the goal in the imperialist capitals has never been simply to “contain” Russia, which in the 1990s was economically prostrated and militarily weak. Even at that time, the swamp-monsters of Washington were projecting how Russia might be isolated, permanently weakened, and if possible broken up, in order to be more readily dominated and exploited.

Over the past twenty years, the political dynamics of Ukraine have been an important additional part of the picture. Nevertheless, it must be recognised that for the imperialists, Ukraine has never been the main game. Its role in the greater Western gambit has been to provide excuses, battlefields and expendable human flesh.

It is worth recalling that in the 1990s — and for a considerable period beyond — tensions between Ukraine and Russia were minimal. The two economies were tightly intermeshed, and polling showed Ukrainians as more inclined to view NATO, not Russia, as the primary threat to their interests. To turn Ukrainians against Russia would take decades of intensive Western psy-ops, involving persistent and lavishly funded massaging by imperialist operatives, of Ukrainian public opinion.

By the time of NATO’s 2008 Bucharest conference, and arguably years earlier, the perspectives of the NATO countries vis-à-vis Russia had formed themselves into a sort of dual ultimatum. Russia was to be offered two alternatives: either suffer endlessly mounting threats and strictures, from people who regarded adherence to signed-and-sealed treaties as optional; or go to war. The Russians chose the latter — but only after multiple offers of negotiations, lasting until the early months of 2022, had proved unavailing.

For anyone tempted to moralise about “Russia’s brutal war”, this situation should prompt some reflection. The imperialists undoubtedly understood that if they kept escalating their threats, war was effectively inevitable. The people in the Kremlin have never been pacifists, and the renewed humiliation and subjection the imperialists offered Russia as an alternative to war would, in any case, have been rejected as unendurable by huge numbers of Russian citizens. In the worst case, such a war would be drawn-out, bloody and incalculably expensive, above all for the Ukrainian masses. But the Western powers were not deterred.

In launching their “special military operation”, the Russian authorities appear to have calculated that a swift occupation of strategic territories in the north, south and east of Ukraine would bring the Kyiv regime — and at least some people in Western capitals — to their senses. Backed by facts on the ground, serious negotiations could then begin toward a lasting settlement.

It is a matter of historical record that this Russian strategy almost worked. In late March 2022 peace talks between Ukraine and Russia opened in the Turkish city of Istanbul. Ukrainian lead negotiator Davyd Arakhamia later stated, Ukrainian neutrality was “the biggest thing” for the Russians: “They were ready to end the war if we accepted ... neutrality and gave commitments that we would not join NATO”.

Donald Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff was later to recall that the two sides engaged in “cogent and substantive negotiations”, and “came very, very close to signing something”. In an article in the US journal Foreign Affairs, scholars Fiona Hill and Angela Stent concluded that the negotiators “appeared to have tentatively agreed” that Russia would agree to withdraw to its pre-invasion positions.

Then on 9 April British Prime Minister Boris Johnson turned up in Kyiv. According to sources close to Zelenskyi, quoted by the news site Ukrainska Pravda, Johnson arrived “almost without warning”, and brought two simple messages:

The first was that Putin was a war criminal, who should be pressured, not negotiated with.

The second was that even if Ukraine was ready to sign some agreements on guarantees with Putin, they [the British government] were not.

Johnson’s position was that the collective West ... now felt that Putin was not as powerful as they had previously imagined, and that there was a chance to “press him”.

The talks in Istanbul promptly expired. Zelenskyi, it is evident, believed assurances from Johnson that the leading NATO countries would bolster the Ukrainian forces with new military supplies and strangle Russia with sanctions. Ukraine’s leaders doubled down on what has been the country’s persistent tragedy — a delusional belief that imperialism, somehow, has Ukrainian interests at heart.

From being a limited foray intended as “shock therapy” for Ukrainian and Western leaders contemptuous of Russian interests, the “special military operation” before long was transformed into the most extensive conflict to unfold in Europe since 1945. Does this mean it has been “counterproductive” and “a gift to NATO”, as Slee maintains?

In the first place, it is hardly the task of the left to second-guess the bourgeoisie, pronouncing on the advisability, or otherwise, of strategies designed to benefit an alien class. But if we must, nevertheless, play at being capitalist policy-makers, and weigh the conflict and its outcomes against the alternatives that were before Putin and his advisors, does the “special military operation” measure up?

Compared to an option that the Russian leadership certainly did not consider — the consistent, militant defence of working-class interests at home and abroad — the “special military operation” definitely earns a failing grade.

What of another choice that Putin and his associates might have weighed up: the choice of going on their knees and accepting the dictates of global capital? To suggest that renewed Western hegemony over Russia would be mellow and undemanding is to fail to take imperialism seriously.

Meanwhile, there was also the question for the Kremlin leaders of whether the Russian population, who remember the Yeltsin era, would have tolerated such a betrayal.

What should socialists call for?

So far, this text has merely sought to interpret the Ukraine conflict. The point, however, is to end it.

How, and on what terms? Slee argues that “socialists should condemn Russia’s invasion, and campaign in solidarity with anti-war forces in Russia”. But to “condemn Russia’s invasion” is to confuse consequence with cause.

The Russians plainly did not want a war, and worked hard to avoid it. They moved against Ukraine only when they had concluded that there was no reasonable prospect of peace, and that the threat they were exposed to had become intolerable.

For the left to focus blame on the Russian side leaves the NATO powers, which engineered the preconditions for the conflict, effectively unadmonished. Nor does it call down justice on the Ukrainian ultra-nationalists, including many in the country’s ruling circles, who joined in the aggressive fantasies of the imperialists, despite the well-documented sentiments of Ukraine’s popular majority.

Slee goes on to acknowledge that a Ukrainian military victory is “scarcely in prospect” and that, as a result, “we should be calling for a ceasefire”. On the face of it, this is a much more civilised position than the demand — still on the books of left organisations in Europe and elsewhere — according to which Russian forces should withdraw from all former Ukrainian territory they currently occupy. The effect of such a withdrawal would be to hand the populations of the Donbas and Crimea over to the vengeance of Ukrainian neo-fascist units, such as the Azov Brigade and Aidar Battalion.

The Russian government is acutely wary of the call for a “ceasefire” and with reason. Given the history of deceptions and broken promises by the NATO powers, Russian authorities evidently foresee that such a ceasefire would be used to allow Kyiv’s imperialist allies to rebuild and rearm the battered Ukrainian forces, while temporising on a lasting peace deal and contriving excuses to resume the fighting from an improved strategic position.

For the world left, the appropriate demand is not a ceasefire but a lasting peace settlement, backed by the most robust international guarantees that can be negotiated. The Russian government has proposed its terms for such a settlement. Principally, these include guarantees that Ukraine will not join NATO and become permanently neutral; that the traditionally Russian-speaking provinces of Crimea, Lugansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson will be recognised as Russian territory; that Ukraine’s armed forces will be reduced to the point where they cannot threaten neighbouring countries; and ultraright elements will be purged from Ukraine’s state apparatus.

Beyond question, there are points here that would involve injustices. There are many people in the disputed territories, and particularly in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson provinces, who have no wish to live under the Russian state. But you cannot have national rights — or sovereignty, or unbreachable security guarantees — if you are dead.

In any war, after victory has ceased to be a realistic prospect, there comes a point where the implications of continuing to fight approach national extermination. The killing in the Ukraine conflict has been monstrous. Now it must stop, on whatever terms might plausibly be enduring. For the international left that means, in practice, calling for acceptance of the peace terms, outlined above, put forward by the Russian side.

Against this, we have Slee’s final serve:

If Russia does not agree to a ceasefire, then we should call for Ukraine to receive the military aid it needs to prevent Russia conquering even more Ukrainian territory.

In other words, the fighting should grind on — presumably, until Ukraine’s male population is reduced to the point where national recovery has become biologically impossible. Meanwhile, Slee’s suggestion that socialists around the world should call on Western governments to step up their military assistance to Ukraine is deeply disturbing in itself. The same, indeed, can be said of a great deal of the Western left discourse on the Ukraine conflict.

For the international left to play a constructive role in ending the slaughter of the Ukrainian people will require a radical improvement in the quality of left-wing debate. The assumption that Ukrainian history began in February 2022 must be banished, to be replaced by serious research and discussion, reaching back many decades, on how the present debacle came to pass.

The demonisation of Russia must cease, giving way to reasoned consideration of how Russian policy-makers perceive their interests, and allowing them due credit for their efforts since 2014 to quell the fighting.

On the theoretical plane, the left in Western countries needs to return to its Leninist roots, and refine its understanding of imperialism. Liberal accretions, with their origins in the attenuated Marxism of university departments, must be cut away. Progressive people must relearn the analytical skills needed to distinguish between international capital and its victims.

Boris Kagarlitsky: Economic preconditions for peace

First published in Russian at Rabkor. Translation by Dmitry Pozhidaev for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

Assessing Russia’s economic situation at the end of 2025, Ekaterina Shulman, who has been designated a “foreign agent,” suggested that the country is running out of money and people. And indeed, by all indications, something is running out. Only it is not money, at least not primarily. The state will never run out of money.

The peculiarity of liberal experts’ thinking is that they reduce everything to money. Yet money is merely an instrument used to redistribute other resources. Of course, if you mindlessly print it, it loses value. We know eras when even gold and silver depreciated. But the fundamental question is which resources are being distributed, and how, through government spending. And those resources are always limited (which is, in general, the essence of economics as the science of working with scarce resources); they really do have a tendency to be exhausted.

People, the personnel reserve for both war and production, are also a resource, and an extremely limited one. The days when, like an eighteenth-century Russian officer, one could proceed from the idea that “women will just give birth to more,” are long gone. But during wartime, no fewer problems arise with other resources: metal, fuel, electricity, railway capacity, equipment that becomes obsolete and wears out, and so on. The outcome of a military campaign depends to a large extent on how all these means are allocated.

The well-known Soviet economist Yu. V. Yaremenko, developing the concept of a multi-level economy, drew attention to the fact that resources also differ in quality. Just as metal can be good or not so good, specialists can be top-class or not very competent. In the Soviet Union, the military-industrial complex, in unlimited volume, absorbed all the best resources. The remaining sectors of the economy had to compensate for lack of quality with quantity. And the lower a branch’s priority, the worse things were.

If we return to the question of labour resources, it turns out that under such an approach, civilian production begins to suffer chronic staff shortages even if, on paper, there seem to be enough people. After all, the best specialists are needed precisely where resources are scarce, and where their intelligence, talent, and experience can fix the situation, figure a way out, invent something new. But in practice it works the other way around. The best technical minds are already concentrated in the defence industry, while the other sectors are kept on starvation rations.

The trouble is that the growing crisis in civilian production begins to affect the economy as a whole, spreading from the bottom up. In the end, workers in the defence industry also need to buy clothes and eggs, take their children to kindergartens and schools, get treated in clinics, and so on. The country’s leadership recognises the problem, but this is where difficulties with money arise. And in Russia’s market-capitalist economy, they turn out to be even greater than in the Soviet Union’s administrative-planned economy.

As already noted, liberal economists, including those working in the government, see any problem as a money problem and solve it accordingly. Under “normal” conditions this more or less works, but not under crisis conditions. Crisis situations differ precisely in that habitual methods not only fail to produce the expected effect, but often make things worse.

The specificity of the current crisis is that the economic authorities, in full accordance with the doctrine of financial management, are concerned not only with covering an objective shortage of resources through injections of additional money (a shortage that will not disappear anyway), but also with maintaining stability: in 2025, financing of priority sectors and projects is combined with strict austerity and an even stricter fiscal policy, in an attempt to restrain price growth and balance the budget. The main result of this approach is a deepening of disproportions in the economy and society.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), an alternative to classical liberal economics, is far more indulgent toward printing money and does not see a major catastrophe in an increasing budget deficit, which by the end of 2025 had already exceeded four trillion rubles. But there is an important nuance: MMT theorists propose directing additional money to where there are underutilised resources that can be brought into circulation through public financing. For example, you have a mineral deposit but no investors. Or you have many unemployed people who can be employed in socially useful work.

In our situation, everything is exactly the opposite. The Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance throw money not where there is resource potential, but where there are no available resources left. And increasing funding will not make them appear. Metal will not smelt itself, and soldiers will not grow out of the ground, even if you sow the whole earth with dragon’s teeth, as the heroes of an ancient myth did.

Moreover, there is another limited resource: time. Only God has an infinite supply of it, and even that is conditional on His existence. For mortals, time is not only limited but nonrenewable. In other words, because of earlier mistakes and missed opportunities, it is often impossible to make it up later.

In spring and summer 2024, when it seemed that the domestic economy was coping fairly well both with sanctions and the burden caused by military expenditures, measures could have been taken to ration resources so as to protect the civilian sector from shortages and the financial system from spontaneous price growth. But why bother, if at that moment everything seemed fine anyway. And if, as many expected, a peace agreement had been reached between autumn 2024 and spring 2025, temporary difficulties most likely would not have grown into a full-blown crisis.

But that moment is already past. Resource scarcity has intensified, taking for the authorities the form of a critical shortage of money. Further increases in financing for priority sectors and programs will only lead to further growth of imbalances and the final destabilisation of the monetary system, as well as a worsening social crisis, when entire sectors of the economy and social groups left on starvation rations will be unable to provide even the minimum necessary level of investment for their own reproduction.

The authorities understand this situation perfectly, and therefore the peacefulness of the ruling circles grows strictly in proportion to the deepening crisis. But the problem is not only that the worsening crisis will inevitably require a reverse redistribution of resources toward civilian sectors; it is also that political and ideological questions arise, questions that can be brushed aside only as long as military actions continue.

Moreover, this reverse redistribution will be associated with making a whole series of difficult decisions. It can be carried out by market or administrative methods, effectively or not, but in any case, it is incompatible with escalating the war effort. And even if everything is done competently, the emergence of numerous difficulties and conflicts along the way is inevitable.

The understanding of this by those in power also contributes to the desire to leave everything as it is for a while, without taking irreversible steps. Only, postponing decisions into an indefinite future not only does not make the choice easier, but aggravates existing problems.

Ultimately, the authorities will have to make precisely political decisions. Here, perhaps, we can put a period.

Putin’s Russia: Testing the limits of state-directed mobilization

First published at Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, it boasted a highly globalized economy with its own fraction of the transnational capitalist class. As such, it was vulnerable to Western sanctions and economic decoupling with the West. In 2021, its ratio of imports to GDP was 20.6 percent — lower than India and South Africa, but higher than China or Brazil. Western countries wagered that economic sanctions would be a powerful weapon against Russia’s war machine, and indeed, early into the war Russia’s own Central Bank predicted a 10 percent drop in GDP in 2022.

Ultimately, however, these negative predictions never materialized. Russia’s GDP declined by only 1.4 percent in 2022, and grew by 4.1 percent in 2023 and 4.3 percent in 2024. What are the sources of Russia’s economic resilience? And do they form a sufficient foundation for long-term economic stability?

Decoupling from the West

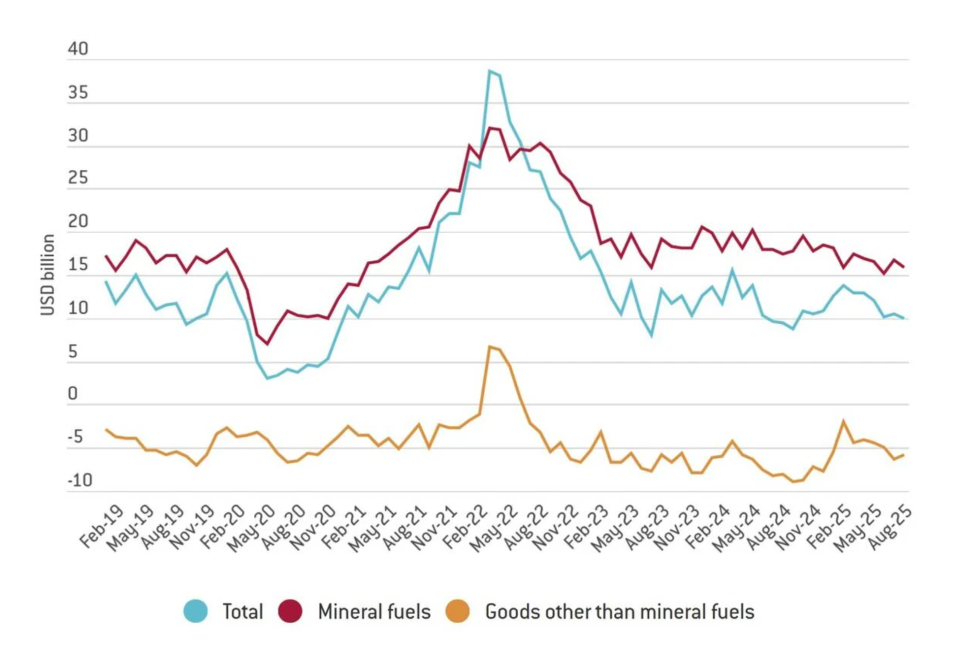

In 2021, Russia accounted for 13 percent of global oil exports. Replacing this amount of oil without causing a global market upheaval in the short term would have proven impossible. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the West ultimately introduced only mild sanctions on Russian oil, such as the 60-dollar price cap, clearly prioritizing stable supplies over geopolitical aims. Similarly, Russian grain and fertilizer exports were exempted from sanctions due to their crucial role in global food security. Consequently, overall Russian exports never collapsed as initially predicted, ensuring a steady supply of foreign currency to purchase imports and tax revenues to fund the war effort.

Some Russian exports did prove to be replaceable. Notably, Russian natural gas exports to the EU were largely replaced by US liquefied natural gas (LNG) and exports from other countries, which caused significant problems for Gazprom, the state-controlled energy corporation. Nevertheless, overall export revenues have remained at an acceptable level.

Russia also benefited immensely from the diversification of the global economy and rise of new, powerful trading partners in recent decades. In 2000, the G7 countries represented 65 percent of the global share of GDP, while BRICS countries collectively accounted for only 8 percent. By 2021, the G7’s share had declined to 45 percent, while the BRICS’s share had risen to 26 percent. Moreover, when measured in purchasing power parity terms, the BRICS’s share of global GDP (31.4 percent) was slightly higher than that of the G7 (30.8 percent).

The sheer scale of non-Western economies is not the only factor here — their complexity has increased as well. The Economic Complexity Index, which measures the sophistication of a country’s export basket, reveals that China climbed from forty-sixth place in the world in 2003 to nineteenth place in 2021. China is now an industrial powerhouse that not only offers some of the lowest prices on the world market, but can produce a wide variety of the most advanced goods and technology.

Had the invasion of Ukraine happened in 2000, Russia’s economy would have been hit much harder by Western sanctions. By the 2020s, however, non-Western countries could absorb most of Russia’s exports and provide most of the necessary imports. For various reasons including both geopolitical as well as purely commercial considerations, non-Western countries have proven reluctant to join Western sanctions against Russia. As a result, decoupling from the West proved feasible. It has proven particularly beneficial to the relationship between Russia and China, which has become an overwhelmingly important trading partner for the former over the last few years.

The role of the state

The Russian state has also occupied an increasingly important role in the Russian economy since the war began. Defence spending is expected to account for 7.5 percent of GDP in 2025. While not exactly a “war economy” comparable to World War I or II, where belligerents spent close to 50 percent of GDP on their respective militaries, Russia still represents one of the largest military economies in the world today in both absolute and relative terms.

State-directed military mobilization helped to bolster the economy’s resilience by absorbing unemployment and boosting domestic demand. Indeed, much of the GDP growth in 2023 and 2024 is attributable to military spending.

Since coming to power in 1999, Vladimir Putin has gradually built up state capacity in select government institutions, notably those responsible for economic management (the Central Bank, as well as the ministries of finance and economic development). Moreover, Russian business has developed flexible and resilient corporate structures. Skilful management in both public and private institutions contributed to the economy’s overall adjustment capacity.

Additionally, Russia already had experience in at least partial decoupling from the West and resultant economic crisis in 2014—2021. Adjustment mechanisms such as import substitution and new channels of state-business interaction developed during that period helped to adapt to the crushing sanctions of 2022 and beyond.

Winners and losers

Wartime economic changes produced new patterns of winners and losers — both in society at large and among the elite. These changes emerged as a result of several processes, including sanctions and the exodus of Western companies, the shifting geography of international trade, the expansion of the domestic military-industrial complex and reconstruction in occupied territories, as well as payouts to soldiers fighting in Ukraine.

These processes interact with each other in complex ways and often have indirect consequences. For example, waves of hiring in the military-industrial complex have put upward pressure on wages across the board. Wage growth in turn leads to inflation in the form of a wage-price spiral. The Central Bank targets inflation by raising the base rate. Along with tax increases, high interest rates reduce investment in civilian industries. While some economic sectors and segments of the population have benefitted significantly from these trends, others have proven far less fortunate.

Overall, Russia’s wartime economy is characterized by very low unemployment (2.2 percent in September 2025, compared to 4.3 percent in 2021) and strong growth in real wages (8.2 percent in 2023 and 9.1 percent in 2024, compared to 3.3 percent in 2021). That said, wage growth has proven highly uneven between regions and industries.

Among the “winners” in terms of rising bank deposits and incomes as well as poverty reduction are the regions with high army recruitment numbers, such as the republics of Tyva and Buryatia or the Altai Republic. Tyva, which by late 2023 counted the highest military losses in the country (140 soldiers killed in action per 100,000 people), also recorded the highest reduction in poverty in 2023 compared to 2021 (5 percentage points) and the strongest growth of local bank deposits (107.3 percent). Payouts to soldiers and their families in case of death have been so high that they are reflected in regional income and poverty statistics.

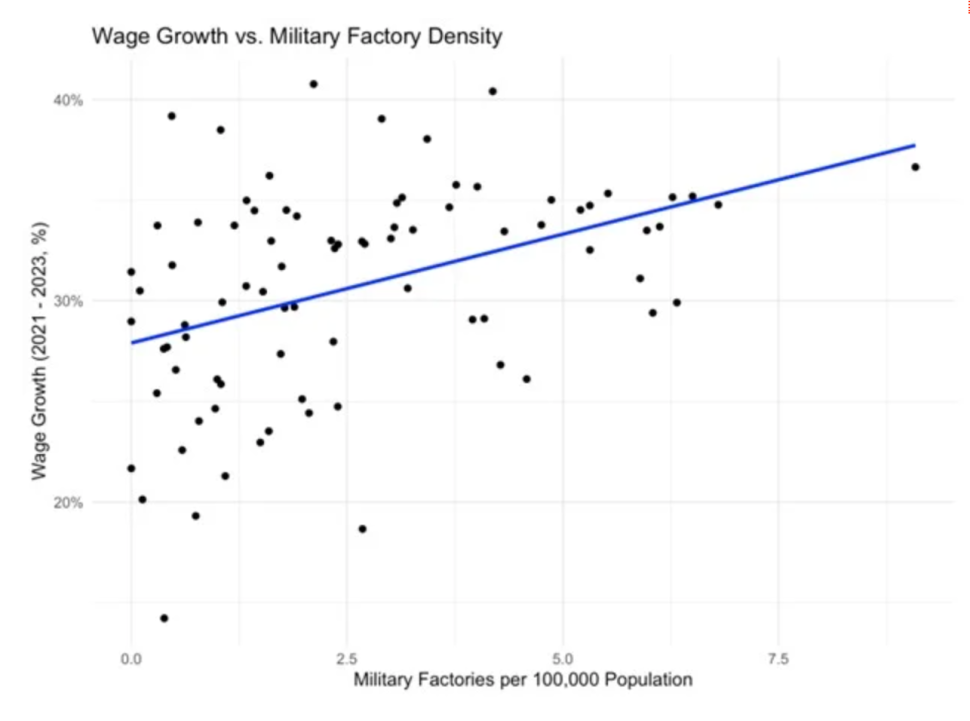

The expansion of the military-industrial complex has transformed Russia’s economic geography even further. In September 2024, authorities reported that 600,000 people had taken jobs in the military industry since February 2022. This growth has been concentrated in regions with existing military production facilities such as Nizhny Novgorod Oblast and Sverdlovsk Oblast. Consequently, these regions have experienced a faster rise in average wages than other regions. As can be seen in the table below, the number of military factories per 100,000 people in a region was associated with stronger wage growth in 2023 compared to 2021. A similar picture emerges from economic statistics, where military-related industries have seen the strongest growth in wages.

Large cities, particularly Moscow and Saint Petersburg, have been the losers in this situation. Their advanced post-industrial economies, although large and flexible, have suffered the most from deglobalization and the breakdown of international economic ties. In terms of wage growth, Moscow is in seventy-seventh place out of 85 regions (Russian statistics include occupied Crimea and Sevastopol), while Saint Petersburg is in sixty-sixth place. Both cities demonstrate similarly weak performance in terms of real income and bank deposit growth as well as poverty reduction compared to 2021.

The losers in terms of industries are oil and gas production, as well as public services such as education, healthcare, and social work. The oil and gas sector already boasted high salaries prior to the war and experienced significant turbulence and readjustment in the years since the invasion began. The weak wage growth in public services testifies to underinvestment, with the government prioritizing military spending over social expenditure.

Overall, the militarization of the Russian economy and forced import substitution acted as a corrective to post-Soviet economic tendencies. Since the early 1990s, Russia’s industrial working class and regions with a high concentration of Soviet-era industries (including the military-industrial complex) were among the losers of the economic transition, producing widespread misery and destitution. Since 2022, however, industrial workers and industrial regions have seen their fortunes improve somewhat.

Many Russians welcomed this development, viewing it as a remedy for one of their country’s most glaring economic and social imbalances. Nevertheless, the scale of this effect should not be overstated, and the weaknesses of the wartime economy remain significant.

Elite blowback

The war set in motion powerful processes, leading to a restructuring of the Russian business class as a whole. While a segment of the highly internationalized elite chose to cut ties with Russia, others doubled-down on their support for the current political order and have done their utmost to profit from the new situation since.

At least nine billionaires from the Russian Forbes list went as far as renouncing their Russian citizenship. Others completely divested from Russia and moved abroad while nominally remaining citizens. Other capitalists went all-in on Russia, rolling up the assets left by Western companies leaving the country. According to The Bell, the 2021 revenues of the companies that changed hands in this way amounted to roughly 3 trillion roubles, or 2.2 percent of Russian GDP. At the same time, the government launched an unprecedented wave of nationalizations. According to Novaya Gazeta, by March 2025 at least 2.56 trillion roubles’ (almost 2 percent of GDP) worth of assets had been nationalized.

Prior to the war, the Russian business community had access to a kind of “exit” option, as Russian corporations were simultaneously enmeshed in domestic state-capitalist networks as well as the global networks that constitute the transnational capitalist class. This arrangement allowed them to balance their domestic and foreign interests. The beginning of full-scale hostilities, however, forced Russian businessmen to make a choice: would they stay, or would they go? Most stayed in Russia, unwilling to let go of their primary revenue streams. This increased their dependence on the Kremlin, whose overwhelming influence over the Russian economy has only grown since 2022.

On the other hand, the lack of an “exit” option, coupled with the fear of losing wealth (e.g. due to nationalization), may eventually force the business class to develop strategies to leverage their political influence. Indeed, prior to the war, the political neutralization of the Russian business class had been so effective precisely because it maintained an exit option, able to choose partial or complete divestment over any attempts at political organization. Now that this route is closed off, Russia’s remaining billionaires may realize that they are stuck with Putin and that their wealth is under constant threat, necessitating new defensive strategies. Hence, it is becoming increasingly important for the Kremlin to manage the fears of the business class and maintain profit opportunities, lest dissatisfaction in the corporate sector grow.

Exhausting the wartime model

While the Russian economy has proven resilient in the face of powerful shocks, the limits of the wartime model are increasingly obvious. After two years of growth exceeding 4 percent, the Central Bank projects only 0.5–1 percent growth in 2025. Civilian industries are in sustained decline. High interest rates are a burden on the corporate sector, while investment — especially capital investment — is down.

The government has consistently raised taxes to finance its enormous military expenditures. For example, the corporate tax rate was raised from 20 to 25 percent, value added tax will increase from 20 to 22 percent in 2026, and personal income taxes are now collected on a progressive scale with a top rate of 22 percent (compared to 15 percent prior to the war).

Hundreds of thousands of skilled specialists have emigrated, and the gap in educational investment compared to top-performing economies, particularly China, has grown. Labour shortages are draining the civilian sector. Recent US sanctions against major Russian oil producers Rosneft and Lukoil left a sting, with Lukoil forced to sell off its assets in dozens of countries. Opportunities for technology transfer are now limited to non-Western countries, but China’s economically nationalist orientation makes it reluctant to share technologies with Russia (or anyone else, for that matter).

Moreover, the growth in real incomes for the lower classes is, to some extent, a statistical artefact. Prices are rising unevenly, with the cost of basic necessities like food, housing, and utilities rising faster than that of other goods and services. “Poor man’s inflation” is effectively higher than official inflation figures, largely negating income gains for the lowest-paid workers and pensioners.

In sum, despite initial signs of resilience and a surprising recovery, the Russian economy is now back on a trajectory of long-term stagnation — even if the nature of that stagnation differs from the pre-war period. Transnational ties are now largely limited to non-Western countries, and the war effort is draining resources from the civilian sector without producing any significant economic multiplier effect. Long-term prospects are further undermined by a decline in human capital and a lack of opportunities for technology transfer.

Thus, “Fortress Russia” is certainly resilient, but the development gap with the Global North and the most successful developing economies, particularly China, is widening. Under the current political and economic conditions, it seems highly unlikely that Russia will be able to catch up.

Ilya Matveev is a political scientist specializing in Russian and international political economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment