World’s Fastest Nuclear Force Ramp-Up: Strengthening for China’s 2027 Goal Despite Disciplinary Removals

Andrew S. Erickson, “World’s Fastest Nuclear Force Ramp-Up: Strengthening for China’s 2027 Goal Despite Disciplinary Removals,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 27 December 2025.

Amid the most dramatic military buildup since World War II, as part of the world’s most rapid and extensive nuclear weapons buildup, China continues to develop its nuclear triad. The Pentagon’s 23 December 2025 China Military Power Report assesses that Beijing has grown its operational nuclear warhead stockpile from the “low 200s” circa 2020 to the “low 600s through 2024,” and remains on track to surpass 1,000 warheads by 2030.[1] Among China’s three nuclear-capable services, the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) and its supporting defense-industrial base have experienced particularly extensive removals under Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping’s intensified anti-corruption campaigns since 2023. Yet the report repeatedly underscores a double-edged theme: these purges may impose short-term churn and readiness costs, but could well yield a more capable force in the medium-to-long run. Meanwhile, the report emphasizes that the PLA continues to advance toward realizing Xi’s 2027 Centennial Military Building Goal (建军一百年奋斗目标),[2] in which strengthened nuclear deterrence and coercive capacity play a central role. Throughout, the report offers specifics and documentation available publicly nowhere else.

Key Takeaways

- China under Xi is executing a historically rapid nuclear buildup, moving from several hundred operational warheads to the current 600+ to potentially over a thousand within this decade, while simultaneously diversifying its triad.

- Beijing is pursuing capabilities—a maturing triad, low-yield theater systems, and an early warning counterstrike (EWCS) posture—that offer more flexible options at manifold rungs of the escalation ladder.

- Massive anti-corruption purges in the PLARF and defense industry supporting it, while destabilizing in the near term, are explicitly framed by Pentagon’s 2025 report as enabling a more effective nuclear force if underlying problems are properly remedied.

Goals and Priorities

This year’s edition for the Pentagon’s report provides its clearest public articulation yet of Xi’s 2027 goal. It notes that Beijing first publicly unveiled this objective in October 2020 at the 19th Central Committee’s 5th Plenum, but that the target was internally established at an expanded Central Military Commission (CMC) meeting in late 2019. PRC media and commentary link this goal to building capabilities to confront U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific and to “coerce Taiwan’s leadership to the negotiation table on Beijing’s terms.”

The PLA ties achieving the 2027 goal to developing “three major strategic capabilities” that the report interprets as follows (excerpted verbatim from p. 16):

- “Strategic decisive victory” (战略决胜): This likely requires the PLA to be credibly able to prevail in a conflict at acceptable cost. The PLA probably tracks this requirement to a Taiwan conflict with U.S. involvement, which is the most stressing contingency the PLA plans against.

- “Strategic counterbalance” (战略制衡): This likely requires the PLA to build up its means of strategic deterrence—including nuclear deterrence—to sufficiently deter or restrain U.S. military involvement. The PLA, viewing itself as militarily weaker than the United States, contextualizes counterbalance as a means by which the weak offsets the advantages of the strong. Accordingly, it views modernizing its nuclear capabilities in line with strategic counterbalance to address a disadvantage vis-à-vis the United States.

- “Strategic deterrence and control” (战略慑控): This likely requires the PLA to have the force capacity to limit horizontal escalation or dissuade other states from taking opportunistic actions.

Within this framework, Xi has clearly elevated nuclear weapons as core to realizing PRC great-power status, constraining American options, and coercively enveloping Taiwan. The central importance of nuclear weapons capabilities to these top-priority aims readily explains unprecedented nuclear emphasis and development throughout the thirteen years-and-counting of his rule. China’s strategic rocket force was known as the Second Artillery Corps from its establishment in 1966 until its redesignation under Xi as the PLARF at the end of 2015 following its elevation from a military branch to a full-fledged service. In early December 2012, just nineteen days after taking power as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the CMC on 15 November, Xi convened the generals overseeing the Second Artillery (pre-PLARF), which he termed a “pillar of our status as a great power.” He charged them with advancing “strategic plans for responding under the most complicated and difficult conditions to military intervention by a powerful enemy”—standard PRC wording to describe the United States. Just over thirteen years later, we are witnessing ongoing results of Xi’s effort.[3]

Historical Foundations: From Mao’s Priorities to an Emerging Triad

All great waves originate some distance out at sea. China’s current nuclear force surge rests on decades of sustained investment in warheads and missiles. Developing nuclear weapons and the ballistic missiles to credibly deliver them was a top priority for Mao beginning in the 1950s as he sought to deter superpower attack while ensuring China’s own great power status. Beijing’s nuclear weapons and strategic missile programs benefitted from consistent top-level resource allocation, as well as the greatest insulation of any military programs from the explosive political disruption that derailed China’s aviation industry and many other sectors. Even as Mao sought to limit overall military expenditures, he lavished tremendous funding on China’s nuclear weapons complex. In their canonical study, China Builds the Bomb, John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai estimate that by 1964 Beijing had spent more on nuclear weapons development than on the entire defense budgets for 1957 and 1958 combined—extraordinary resource dedication for a then-impoverished, autarkically isolated state.[4]

Mao similarly prioritized nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarine (SSBN) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) programs after the mutual collapse of a Soviet joint development proposal in 1959, famously vowing: “We will have to build nuclear submarines even if it takes us 10,000 years!”[5] China’s first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the DF-5/5A, reached initial operational capability around 1981, giving Beijing a rudimentary but genuine ICBM capability. PRC nuclear warheads and associated delivery systems have subsequently become much more numerous, diverse, deployable, and hard to counter. Over roughly three-quarters of a century, China has moved from having no nuclear weapons to possessing the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal, trailing only the United States and Russia and increasingly closing key capability gaps.

Current Forces and Activities: A Rapidly Expanding Triad

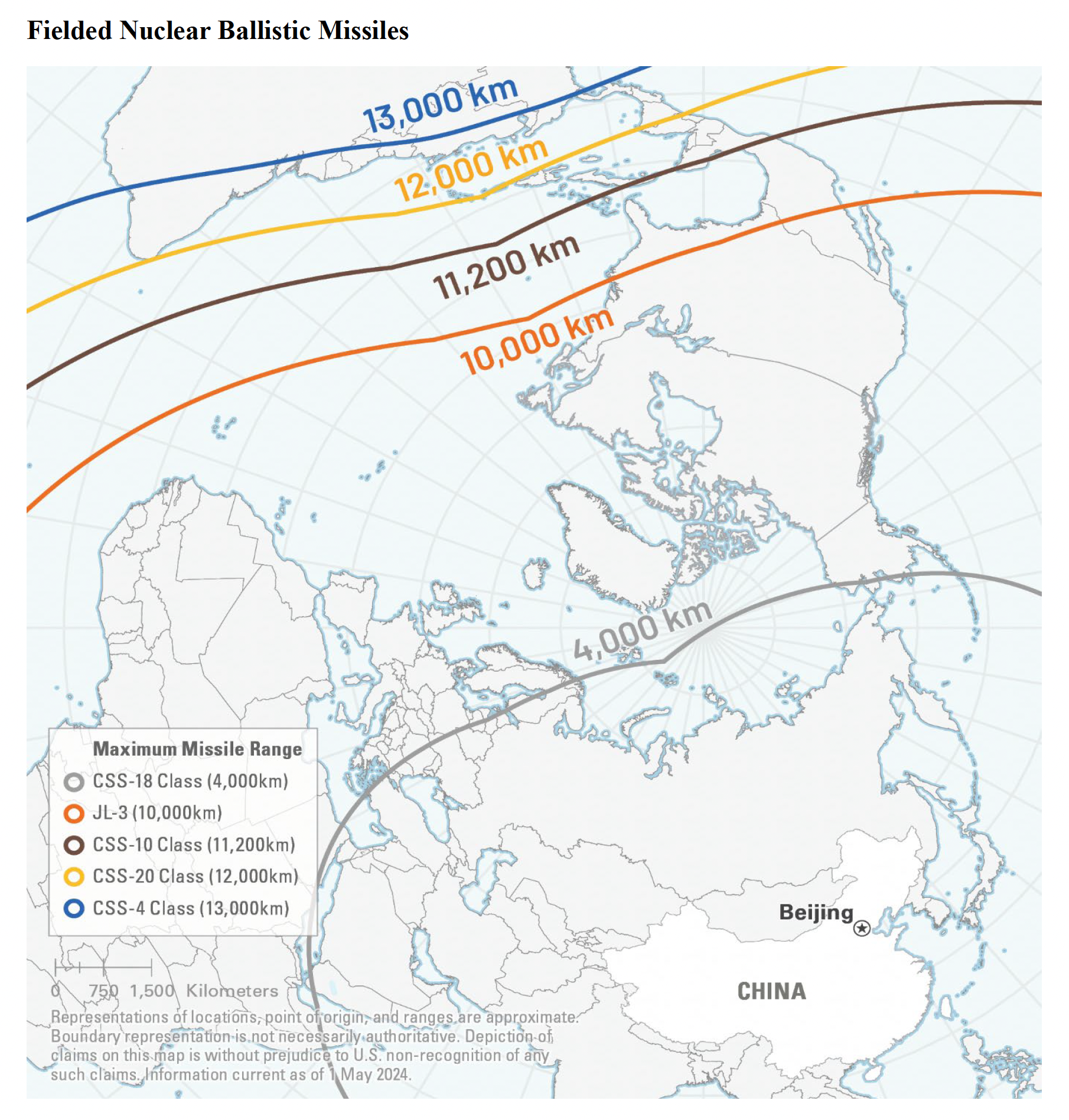

Since just after coming to power, Xi has directed a major nuclear weapons ramp-up, with important additions and improvements as depicted in the Pentagon’s 2025 report’s “Fielded Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” figure (p. 86, reproduced below). The report puts operational PRC nuclear warheads in the “low 600s through 2024”: “While [an earlier edition of] this report assessed in 2020 that China’s nuclear warhead[s] would double from a stockpile of the low 200s over the next decade, the PLA remains on track to have over 1,000 warheads by 2030.”

It is important to underscore that with regard to PRC nuclear warhead numbers—as with much other data in the Pentagon’s 2025 report—China has had another year of development not captured by the report because of information cutoff and internal review timelines. This lag effect is an unavoidable reality in a U.S. government document prepared systematically for public release, but it is likely accentuated by the fact that this latest Pentagon report—with its 23 December 2025 publication—has appeared the latest in the calendar year of all twenty-five such reports issued to date since the first appeared in 2000. (Thus far, every annual report issued has been published within the same calendar year as that which it is required to report to Congress; none have spilled over into the next calendar year.) At the rate PRC military development is progressing, the 2025 report’s unprecedented latency could well mean that actual statistics and other data currently achieved by China have advanced significantly from those documented in the report.

In any case, the Pentagon’s 2025 report demonstrates clearly that the PLARF is working hard to strengthen its already-extensive land-based capabilities. The report documents several striking recent developments. A central focus is China’s effort to achieve an EWCS capability, conceptually similar to launch-on-warning (LOW), whereby “warning of a missile strike enables a counterstrike launch before an enemy first strike can detonate.” Accordingly, in 2024 and early 2025 China launched two additional Tongxun Jishu Shiyan (TJS, a.k.a. Huoyan-1) geosynchronous early warning satellites. “China’s early warning infrared satellites can reportedly detect an incoming ICBM within 90 seconds of launch,” the report assesses in exquisite, uniquely authoritative detail, “with an early warning alert sent to a command center within three to four minutes.”

China’s multiple ground-based, large phased-array radars (LPARs) likely support EWCS by detecting incoming ballistic missiles high in the atmosphere thousands of kilometers away; confirming, refining, and fusing data; and thereby facilitating a pre-detonation counterstrike. These radars “probably can corroborate incoming missile alerts first detected by the TJS/Huoyan-1 and provide additional data, with the flow of early warning information probably enabling a command authority to launch a counterstrike before inbound detonation.”

Relatedly, in December 2024, “the PLA launched several ICBMs in quick succession from a training center into Western China, indicating the ability to rapidly launch multiple silo-based ICBMs, as required for an EWCS operation. The PLA has likely loaded more than 100 solid-propellant ICBM missile silos at its three silo fields with DF-31 class ICBMs, which are very likely intended to support EWCS.”

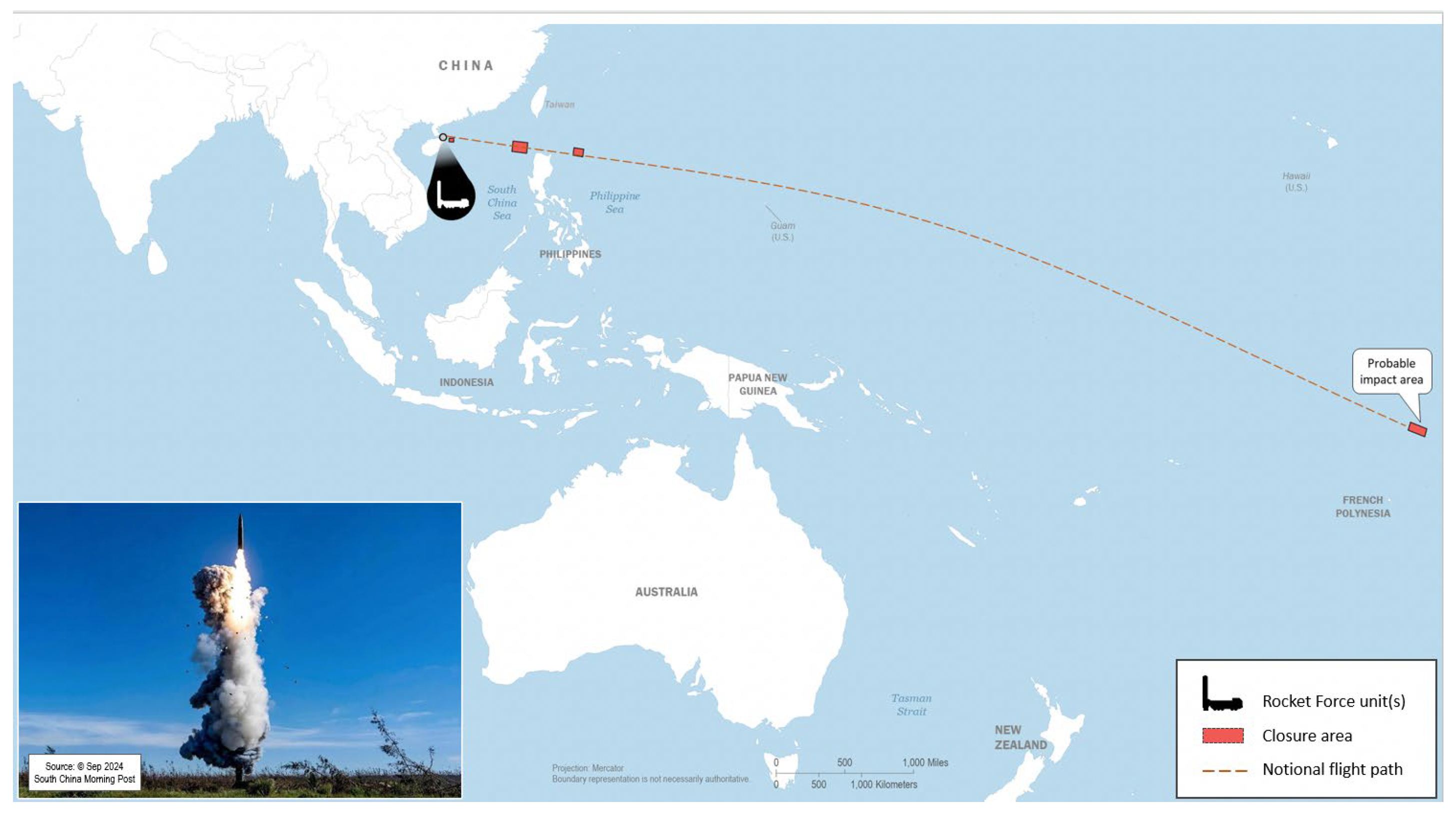

Meanwhile, in the first such open-ocean test since 1980, on 25 September 2024[6] the PLARF launched a DF-31B ICBM from northern Hainan island, which flew roughly 11,000 km before impacting the Pacific near French Polynesia (as seen in figure on p. 29, reproduced above). “The PLA views ICBM launches, including into broad ocean areas during crisis or conflict, as an option for medium-to-high intensity nuclear deterrence operations,” the report judges. “The September 2024 launch probably enabled the PLA to train on the procedures and tactics for this type of operation during peacetime.” It posits that “future launches may occur with some regularity.” Beijing explicitly portrayed the launch as part of routine training but provided pre-notification only to select states.

As part of its nuclear triad’s sea leg, China has now fielded the Julang-3 (JL-3/Great Wave-3) (CSS-N-20) SLBM on its Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs. The Pentagon’s 2025 report assesses the JL-3 at roughly 10,000 km range, enabling strikes on large portions of the Continental United States (CONUS) from suitable patrol areas. The report’s aforementioned “Fielded Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” figure depicts the JL-3’s 10,000 km range covering Washington, DC and most of the continental United States (CONUS), with the exception of Florida and a swath of the southeast.

JL-3 coverage by the Pentagon report in 2025 and over the past decade traces how the sea-based leg has been maturing into a genuinely intercontinental component of China’s deterrent. The 2024 report depicts the JL-3’s 10,000 km range on a similar “Fielded Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” figure (p. 106) to the one in the 2025 report. The 2024 report states that, in “the PRC’s first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent,” the PLAN’s 6 Jin-class SSBNs, each with 12 vertical launch cells, may be equipped with the 5,400 nm JL-3 or the 3,900 nm JL-2 (CSS-N-14). “The PRC probably fielded the extended-range CSS-N-20 (JL-3) SLBM on the PRC’s JIN class SSBN, giving the PRC the ability to target CONUS from littoral waters and enabling the PLAN to consider bastion operations to enhance the survivability of its sea-based deterrent. The SCS [South China Sea] and Bohai Gulf probably are the PRC’s preferred options for employing this concept,” the 2024 report elaborates. “PRC sources claim the JL-3 has a range of over 5,400 nm, which would allow a JIN armed with this missile to target portions of CONUS from PRC littoral waters. The PLAN’s next generation SSBN, the Type 096, is expected to enter service the late 2020s or early 2030s. Considering the 30-plus-year service life of the PRC’s first-generation SSNs, the PRC will operate the Type 094 and Type 096 SSBNs concurrently.”

The Pentagon’s 2023 report has a similar figure and similar wording. The 2022 report does not depict the JL-3 in its “Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” figure. It states that “The PRC probably fielded the extended-range CSS-N-20 (JL-3) SLBM on the PRC’s JIN class SSBN,” followed by the aforementioned bastion-related wording. In its sole mention of the JL-3, the 2021 report explains that “The current range limitations of the JL-2 will require the JIN to operate in areas north and east of Hawaii if the PRC seeks to target the east coast of the United States. As the PRC fields newer, more capable, and longer ranged SLBMs such as the JL-3, the PLAN will gain the ability to target the continental United States from littoral waters,” followed by the aforementioned bastion-related wording. The 2020 report contains a shorter version of this single mention. The 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016 reports posit that the JL-3 will be deployed on the Type 096 SSBN. Pentagon reports from 2015 and earlier do not mention the JL-3 at all.

As the third leg of its nuclear triad, China is also building a nascent air-delivery capability. The PLA Air Force (PLAAF) is modernizing its bomber fleet and developing nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missiles (ALBMs) for the H-6N. Moving forward, the report suggests Beijing is pursuing sub-10-kiloton-yield warheads to fulfill doctrinal aspirations of limited nuclear counterstrikes against military targets while controlling escalation. Among fielded systems, the report identifies the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) and the H-6N bomber’s ALBM as “highly precise theater weapons…well suited for delivering a low-yield nuclear weapon.” On 29–30 November 2024, Beijing deployed nuclear weapons-capable bombers for the first time as part of the PRC and Russian Air Forces’ combined strategic aerial patrol over the Sea of Japan, East China Sea, and Miyako Strait. In this ninth such patrol, PLAAF H-6N bombers joined two Russian Tu-95 bombers.

Corruption, Purges, and Potential Long-Term Strengthening

From mid-2023 onward, the PLARF has been at the center of the most dramatic leadership shakeup in any PLA service in decades. With regard to the personnel leading and supporting China’s nuclear weapons-related operations and the industry supplying them, the report emphasizes both short-term challenges and the potential for medium-to-longer term improvements.

PLARF removals have been widespread and significant: two Commanders and several deputy commanders and Chief of Staff members of the force; related state-owned defense industry seniors; and a top PLARF engineer—all involved in nuclear weapons. As part of replacing the removed, in 2023 China unprecedentedly transferred flag and general officers from the PLAN and PLAAF into the PLARF’s top two leadership positions. Such simultaneous replacement of an existing PLA service’s two top positions—with both posts swapped out on the same day—is likewise unprecedented.

CMSI research documents further that on 31 July 2023, in the PLA’s most dramatic instance to date of a cross-service transfer, Vice Admiral Wang Houbin was appointed PLARF Commander and promoted to full General (3-star).[7]General Xu Xisheng, previously a career PLAAF officer, became PLARF Political Commissar. Notably, CMC second Vice Chairman General He Weidong presided over the promotion ceremony and General Li Shangfu and Admiral Miao Hua both attended; all three CMC Members were later removed—together with General Wang Houbin himself, now deemed a failed replacement.

As further detailed in CMSI research, following reportedly extensive procurement-related corruption during a rapid, massive PLARF buildout, the service was purged severely and continuously from July 2023 to August 2024. At least eight generals were removed, including former Commanders Generals Wei Fenghe and Zhou Yaning, and then-Commander Li Yuchao—the last of whom Wang replaced (for a time); former Deputy Commanders Lieutenant Generals Zhang Zhenzhong and Li Chuanguang; former Chief of Staff Sun Jinming; former Equipment Department Director Lü Hong; and Major General Li Tongjian. On a likely related note, General Li Shangfu was removed in October 2023; before becoming PRC Minister of National Defense, Li had led the CMC’s Equipment Development Department (EDD) (2017–22), where he approved PLA weapons acquisitions.[8]

Disciplinary measures in China’s nuclear industry have been no less extensive, the product of expanded investigations across the defense industrial base. At least five defense-industry leaders—including the head of China’s largest missile manufacturer—were detained by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection for graft associated with weapons procurement; nine related officials were removed from the National People’s Congress (NPC).

“Looking at the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), for example,” the Pentagon’s 2025 report relates, “between December 2023 and December 2024, the Central Commission for Discipline Investigation announced investigations of at least two former division chiefs, one former deputy division chief, and former heads of two CNNC subsidiaries. Yu Jianfeng, the head of CNNC, has missed public activities since at least January 2025, including the March 2025 NPC meeting, indicating that he may also be under investigation. Other personnel moves within CNNC may indicate additional investigations are ongoing.”

The Pentagon’s 2024 report relayed that “At least five PRC defense industry leaders, including the head of the PRC’s largest missile manufacturer, have been detained for investigation by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection [CCDI], the CCP’s top corruption watchdog, likely for engaging in bribery and graft with PLA officers during the acquisition process. In December, nine officials—primarily PLARF and CMC EDD leaders as well as defense industry leaders—were removed from the NPC, the PRC’s national legislature, presumably because of their connections to corruption. In late July 2023, the PLA made a rare announcement, launching a wide-ranging investigation into weapon procurement programs dating back to 2017, signaling significant concerns with the PLA’s modernization efforts more broadly.”[9]

A striking counterpoint to the recent PLARF-linked leadership removals has been the rise of one of the service’s most politically seasoned senior officers: General Zhang Shengmin (张升民).[10] The Pentagon’s 2025 report did not profile his steady, successful career through the service to the pinnacle of PLA power, so it is worth reviewing here. Zhang spent the bulk of his career within the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force and its predecessor, the Second Artillery Corps, developing expertise in political work and disciplinary oversight. In January 2017, he was appointed Secretary of the CMC’s Discipline Inspection Commission (DIC), making him the top military anti-corruption official and a Deputy Secretary of the CCP Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. In October 2017, among other positions, Zhang became one of the four CMC members and one of the eight CCDI deputy secretaries, charged with investigating Party members’ corruption. On 2 November 2017, Zhang was promoted to full General (3-star).

In October 2025, General Zhang was elevated to one of the two vice chairmanships of the CMC. On 28 October 2025, Zhang became the second-ranked CMC Vice Chairman, succeeding General He Weidong following He’s removal amid corruption investigations. On 23 October 2025 General Zhang was added as second-ranked CMC Vice Chairman in a CCP plenary announcement,[11] and subsequent state confirmation on 28 October 2025 finalized his appointment as the second-ranked vice chairman of the CMC.[12] Zhang’s extensive background in internal PLA discipline and oversight positions him as a central figure in Xi Jinping’s ongoing military anti-corruption campaign and may help shape internal reform as the PLARF and broader PLA navigate continuing modernization and accountability pressures. General Zhang’s knowledge of PLARF personnel and investigations must be truly extraordinary, with details that even the Pentagon itself would struggle to deliver. His extensive PLARF and anti-corruption background likely gives him unparalleled insight into internal rocket force dynamics and its associated military-industrial complex—exactly the profile Xi appears to be privileging to steer the force through its current turbulence.

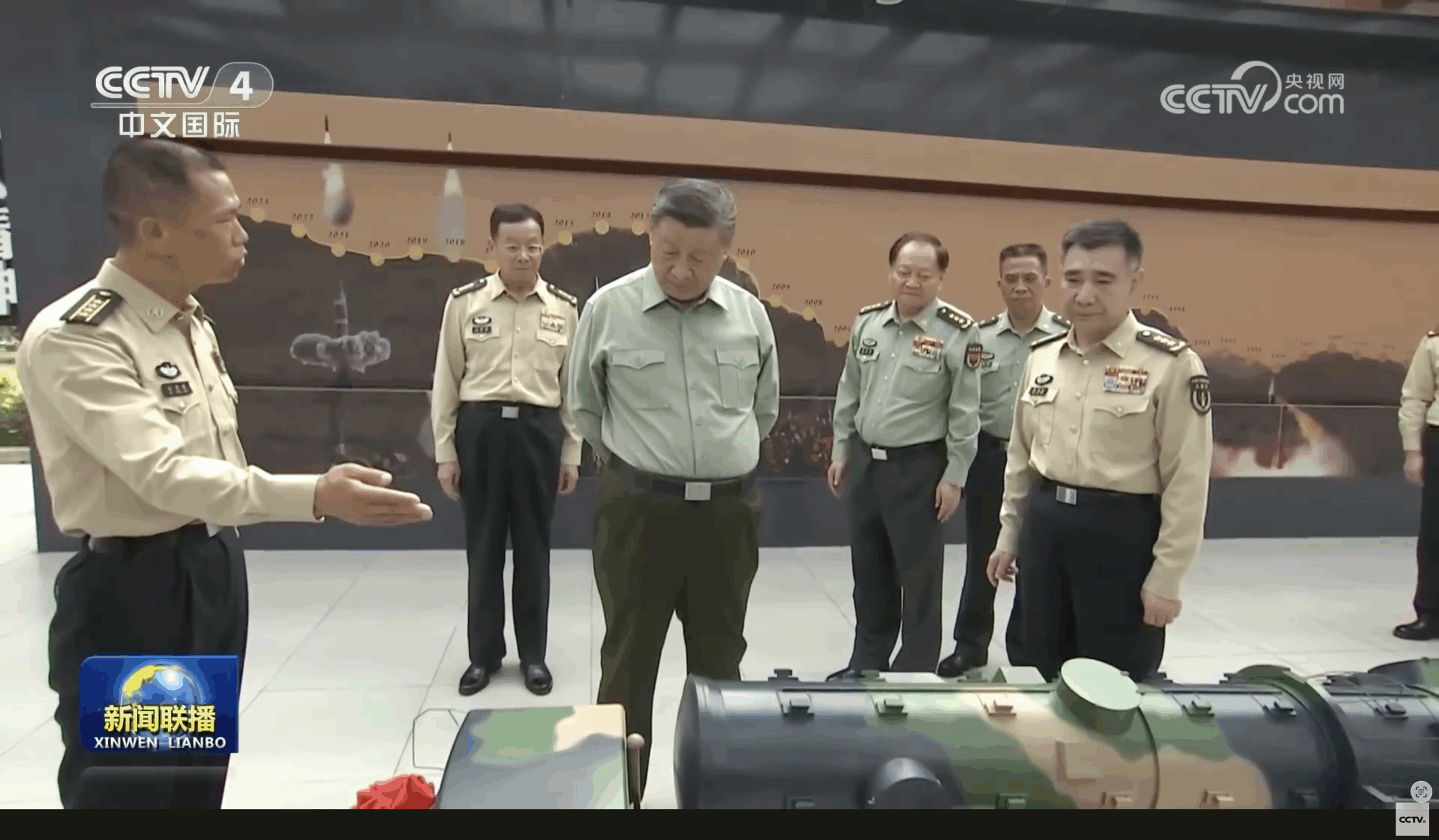

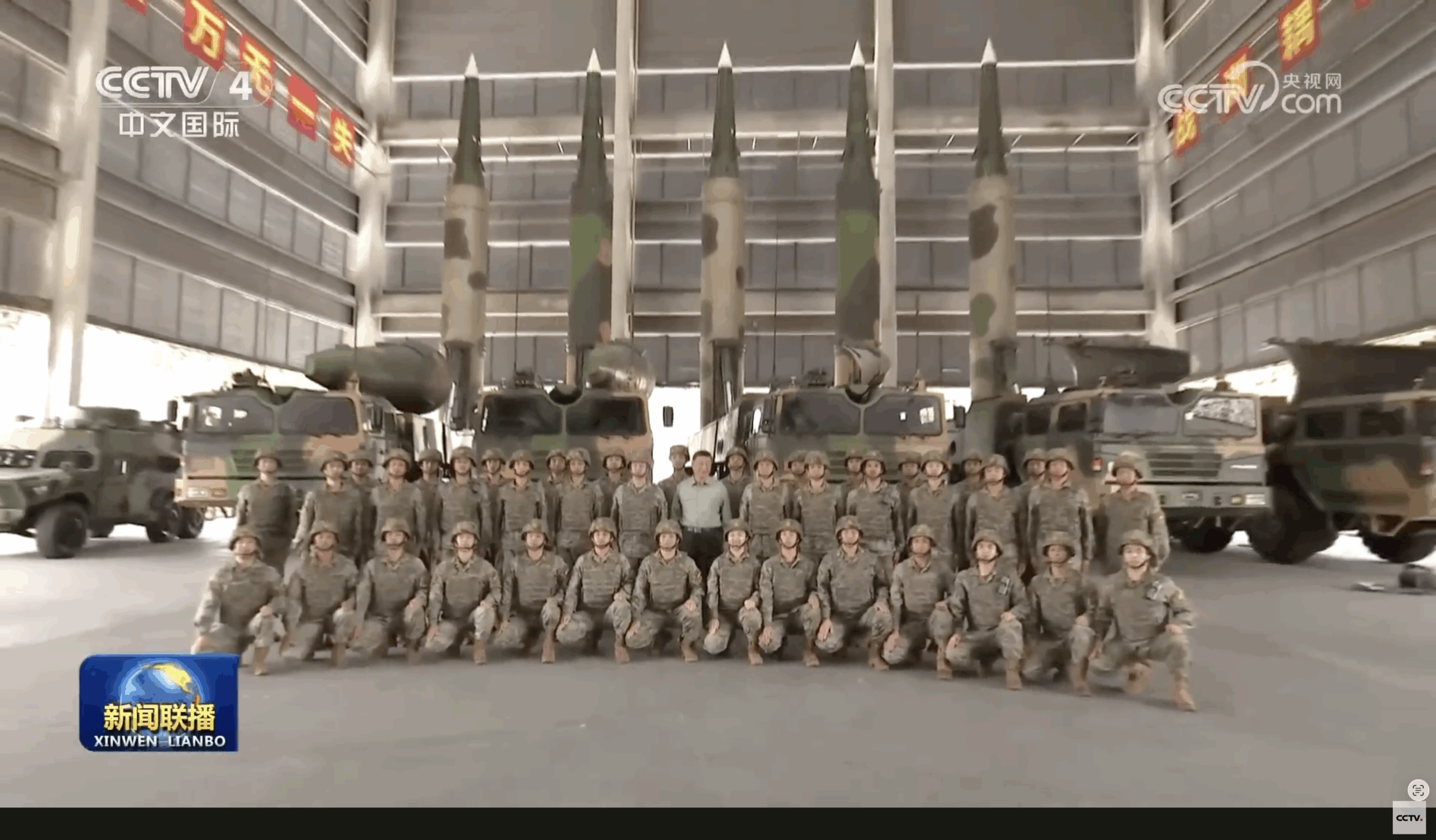

Eyes on the Prize: Xi’s Personal Involvement and Pursuit of 2027 Goal

The report underscores that Xi is personally engaged in managing these risks while pushing to achieve his 2027 goals. In addition to inherent churn, the Pentagon’s 2025 report suggests, the extensive PLARF removals and underlying reasons for them “may be raising questions among leadership about force readiness.” The issue clearly has Xi’s personal attention and prioritization: in October 2024, in his first visit to the PLARF since the recent fusillade of corruption allegations surfaced, Xi inspected the service’s 611th Brigade (in Chizhou, Anhui Province). He addressed Brigade leaders regarding the importance of “military policy, commitment to deterrence, and showing strength and preparedness.” Photos of Xi’s October 2024 visit, not included in the 2025 Pentagon report, follow below.[13]

In sum, the Pentagon’s 2025 report suggests, Xi’s “ongoing anticorruption campaign could have short-term effects on readiness while potentially setting the stage for long-term PLA improvements overall.” Despite the breadth and depth of removals, China under Xi “remains committed” to its 2027 modernization objectives. The 2025 report invokes this bifurcated theme repeatedly when juxtaposing removals in other PLA services with progress toward Xi’s 2027 goal. Relatedly, the Pentagon’s 2024 report seems to further suggest that the PLARF has had serious problems; but, through drastic efforts, has already been strengthened with their being addressed. On the one hand, the 2024 report recapitulates, “The wholesale dismissal of senior PLARF leadership may be connected to fraud cases involving the construction of underground silos for ballistic missiles during a period of rapid expansion for the PLARF and the PRC’s missile industry. The impact on PRC leaders’ confidence in the PLA after discovering corruption on this scale is probably elevated by the PLARF’s uniquely important nuclear mission.” On the other hand, the 2024 report concludes, “This investigation likely resulted in the PLARF repairing the silos, which would have increased the overall operational readiness of its silo-based force.”

As with other aspects of PLA development, multiple things are true at once: short-term readiness risks coexist with the possibility of future advancement if China proves successful in fixing what have clearly been identified as systemic problems. Discoveries of disciplinary violations within the PLARF and its supporting industry have clearly shaken PRC leadership confidence and generated organizational churn. Yet the Pentagon’s 2025 report explicitly warns against assuming long-term weakness: it states that while these purges “very likely” create short-term disruptions to operational effectiveness, China’s nuclear forces could very well emerge more reliable and capable than ever before.

Endnotes

[1] Office of the Secretary of War, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2025 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense/War, 23 December 2025), 28, https://media.defense.gov/2025/Dec/23/2003849070/-1/-1/1/ANNUAL-REPORT-TO-CONGRESS-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2025.PDF.

[2] Andrew S. Erickson, “PRC Pursuit of 2027 ‘Centennial Military Building Goal’ (建军一百年奋斗目标): Sources & Analysis,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 19 December 2021, updated 18 April 2023, https://www.andrewerickson.com/2021/12/prc-pursuit-of-2027-centennial-military-building-goal-sources-analysis/.

[3] Chris Buckley, “China Expands Nuclear Arsenal Under Xi, Bracing for Growing Rivalry With U.S.: Fear and Ambition Propel Xi’s Nuclear Acceleration,” New York Times, 4 February 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/04/world/asia/china-nuclear-missiles.html.

[4] John Wilson and Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), 107–08.

[5] John Wilson and Lewis and Xue Litai, China’s Strategic Seapower: The Politics of Force Modernization in the Nuclear Age (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995), 18.

[6] Greg Torode, “Beyond the Politics, China’s Missile Test Reflects Military Need,” Reuters, 9 October 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/beyond-politics-chinas-missile-test-reflects-military-need-2024-10-09/.

[7] See Andrew S. Erickson and Christopher H. Sharman, “Replacement Removed: VADM/General Wang Houbin—Naval Star Turned Rocket Force Commander’s Terminal Trajectory,” CMSI Note 17 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, 20 October 2025; officially published 13 November 2025), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-notes/17/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 18 December 2024), 159, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Dec/18/2003615520/-1/-1/0/MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2024.PDF.

[10] Yuanyue Dang, Alcott Wei, and William Zheng, “PLA Anti-Graft Chief Zhang Shengmin Promoted to Vice-Chair of Central Military Commission,” South China Morning Post, 23 October 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3330061/china-makes-anti-graft-chief-zhang-shengmin-vice-chair-central-military-commission.

[11] “张升民升任中共中央军委副主席” [Zhang Shengmin Has Been Promoted to Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 23 October 2025, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/china/story20251023-7706798.

[12] 林韵诗 [Lin Yunshi], “⼈事观察|上将张升⺠获任中华⼈⺠共和国中央军委副主席” [Personnel Watch | General Zhang Shengmin Appointed Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China], 财新 [Caixin], 28 October 2025, https://china.caixin.com/2025-10-28/102376607.html.

[13] For details that the Pentagon’s report lacked the space to provide, see “习近平在视察火箭军某旅时强调 坚持政治引领 强化使命担当埋头苦干实干 提升战略导弹部队威慑和实战能力” [During His Inspection of a Brigade of the Rocket Force, Xi Jinping Emphasized the Importance of Adhering to Political Guidance, Strengthening Mission Responsibility, And Working Diligently to Enhance the Deterrence and Combat Capabilities of the Strategic Missile Force], 新闻联播」[News Broadcast], CCTV, 19 October 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLdvaIqYzDU.

No comments:

Post a Comment