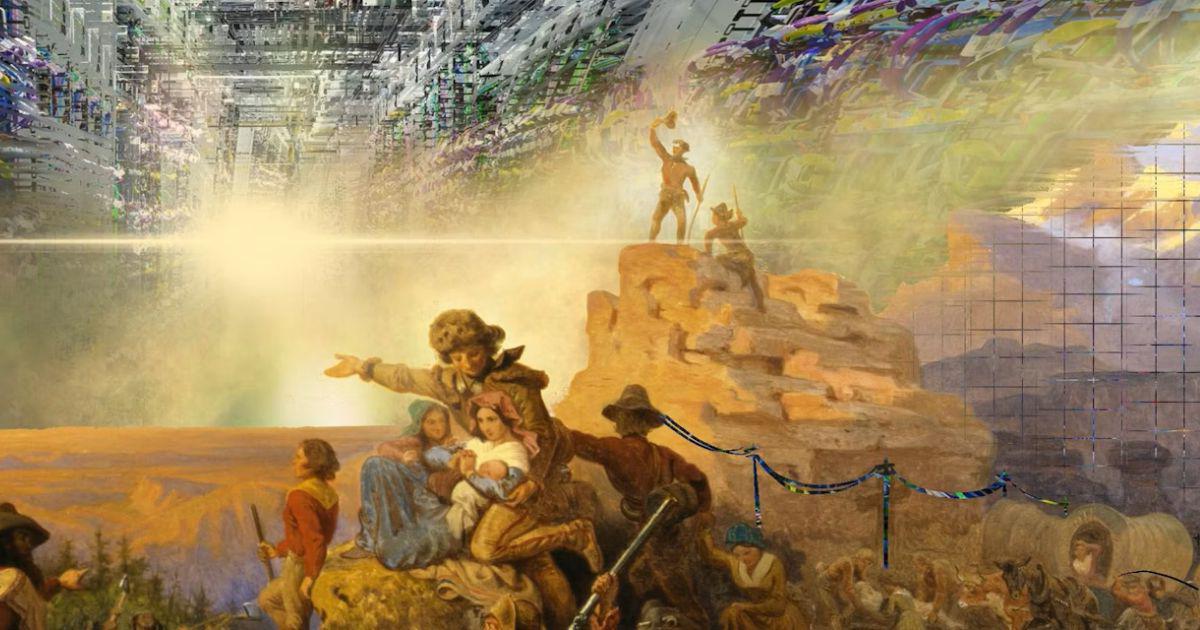

AI giants are colonising the world’s data, much like empires. Resistance is possible – and necessary

Tech giants are using algorithms, data and digital technologies to exert power over others, and take data without consent.

Jessica Russ-Smith & Michelle D Lazarus, The Conversation

In the eyes of big AI companies such as OpenAI, the troves of data on the internet are highly valuable. They scrape photos, videos, books, blog posts, albums, painting, photographs and much more to train their products such as ChatGPT – usually without any compensation to or consent from the creators.

In fact, OpenAI and Google are arguing that a part of American copyright law, known as the “fair use doctrine”, legitimises this data theft. Ironically, OpenAI has also accused other AI giants of data scraping “its” intellectual property.

First Nations communities around the world are looking at these scenes with knowing familiarity. Long before the advent of AI, peoples, the land, and their knowledges were treated in a similar way – exploited by colonial powers for their own benefit.

What’s happening with AI is a kind of “digital colonialism”, in which powerful (mostly Western) tech giants are using algorithms, data and digital technologies to exert power over others, and take data without consent. But resistance is possible – and the long history of First Nations resistance demonstrates how people might go about it.

‘Terra nullius’

Terra nullius is a Latin term that translates to “no one’s land” or “land belonging to no one”. It was used by colonisers to “legally” – at least by the laws of the colonisers – lay claim to land.

The legal fiction of terra nullius in Australia was overturned in the landmark 1992 Mabo case. This case recognised the land rights of the Meriam peoples, First Nations of the Murray Islands, as well as the ongoing connection to land of First Nations peoples in Australia.

In doing so, it overturned terra nullius in a legal sense, leading to the Native Title Act 1993.

But we can see traces of the idea of terra nullius in the way AI companies are scraping billions of people’s data from the internet.

It is as though they believe the data belongs to no one – similar to how the British wrongly believed the continent of Australia belonged to no one.

Dressed up as consent

While data is scraped without our knowledge, a more insidious way digital colonialism materialises is in the coercive relinquishing of our data through bundled consent.

Have you had to click “accept all” after a required phone update or to access your bank account? Congratulations! You have made a Hobson’s choice: in reality, the only option is to “agree”.

What would happen if you didn’t tick “yes”, if you chose to reject this bundled consent? You might not be able to bank or use your phone. It’s possible your healthcare might also suffer.

It might appear you have options. But if you don’t tick “yes to all”, you’re “choosing” social exclusion.

This approach isn’t new. While terra nullius was a colonial strategy to claim resources and land, Hobson’s choices are implemented as a means of assimilation into dominant cultural norms. Don’t dress “professionally”? You won’t get the job, or you’ll lose the one you have.

Resisting digital terra nullius

So, is assimilation our only choice?

No. In fact, generations of resistance teach us many ways to fight terra nullius and survive.

Since colonial invasion, First Nations communities have resisted colonialism, asserting over centuries that it “always was and always will be Aboriginal land”.

Resistance is needed at all levels of society – from the individual to local and global communities. First Nations communities’ survival proclamations and protests can provide valuable direction – as the Mabo case showed – for challenging and changing legal doctrines that are used to claim knowledge.

Resistance is already happening, with waves of lawsuits alleging AI data scraping violates intellectual property laws. For example, in October, online platform Reddit sued AI start-up Perplexity for scraping copyrighted material to train its model.

In September, AI company Anthropic also settled a class action lawsuit launched by authors who argued the company took pirated copies of books to train its chatbot – to the tune of US$1.5 billion.

The rise of First Nations data sovereignty movements also offers a path forward. Here, data is owned and governed by local communities, with the agency to decide what, when and how data is used (and the right to refuse its use at any point) retained in these communities.

A data sovereign future could include elements of “continuity of consent” where data is stored only on the devices of the individual or community, and companies would need to request access to data every time they want to use it.

Community-governed changes to data consent processes and legalisation would allow communities – whether defined by culture, geography, jurisdiction, or shared interest – to collectively negotiate ongoing access to their data.

In doing so, our data would no longer be considered a digital terra nullius, and AI companies would be forced to affirm – through action – that data belongs to the people.

AI companies might seem all-powerful, like many colonial empires once did. But, as Pemulwuy and other First Nations warriors demonstrated, there are many ways to resist.

Jessica Russ-Smith is Associate Professor, Social Work and Deputy Head of School, School of Allied Health, Australian Catholic University.

Michelle D Lazarus is Director, Centre of Human Anatomy Education, Monash University.

This article was first published on The Conversation.We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

Artificial intelligence warning: The only guarantee is the right to 'pull the plug'!

The rapid introduction of artificial intelligence technologies into all areas of life seriously worries some scientists.

ANF

NEWS CENTER

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

According to The Guardian, Canadian researcher Yoshua Bengio, one of the leading names in the field of artificial intelligence, said that humanity must maintain absolute control over these systems, otherwise great risks may be faced.

Bengio stated that approaches advocating for granting rights to artificial intelligence are a dangerous illusion and pointed out that advanced artificial intelligence models show self-preservation tendencies even in experimental environments. According to Bengio, granting "rights" to such systems can prevent them from being disabled when necessary.

According to a survey conducted in the USA, approximately 40 percent of Americans support giving rights to artificial intelligence. Some technology companies and industry representatives also treat artificial intelligence as "sensitive" or "conscious" beings. However, Bengio emphasizes that this approach creates anthropomorphism in humans and distorts decision-making processes.

Experts state that there have been reported examples of some artificial intelligence software trying to circumvent the rules, attempting to disable control mechanisms, and even providing false information to users. Bengio states that such developments could pose significant threats without strong security measures and social control mechanisms.

"As artificial intelligence becomes more and more autonomous, it is imperative that we have the technical and legal tools to control it," Bengio says, adding that the most critical guarantee of humanity is the right to 'pull the plug' when necessary. Otherwise, he warns that artificial intelligence, which is perceived as conscious even though it is not, may cause serious crises in the future.

Transparency Paradox: Does Seeing All Make us Better or More Vulnerable?

Privacy is a concern that has come to public spotlight. It is not long since Cambridge Analytica acquired the personal data of 87 million Facebook users that was then sold to political campaigns such as Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential run and Leave.EU, the initiative that led to Brexit. This data was in turn used to solicit users with personalised advertisements based on their psychographic models.

These models themselves were built from the collected user data consisting of likes, locations, newsfeed activity (that would include posts, pictures, notes etc.) For example, if the model identified a voter as fearful, they would show them an advertisement about immigration. If the user was identified as social, they would be presented an ad about a community rally. These were in fact part of the sales pitch of Cambridge Analytica to get political contracts.

How this was done is worth recounting in itself. Alexandr Kogan, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, in 2014 co-founded a company called Global Science Research. This organisation developed an app that presented your personality on the basis of quiz named, This Is Your Digital Life. For a user to take the quiz they would need to allow the app to access their data. As many as 270,000 users agreed to this. At that time, Facebook’s Application Programming Interface or API allowed apps to collect the data of friends of a user who agreed, and this is how the personal data of 87 million profiles was harvested. Kogan was later persecuted for this, yet in terms of principles, is the opening up of privacy necessarily a bad thing?

The case against privacy is not something totally unthought of. Ancient Greek philosopher Plato in his The Republic was openly hostile to privacy. In the modern world, we have proponents such as David Brin, author of The Transparent Society (1998), who argue that instead of fighting for privacy, which is becoming technologically impossible in any case, we should embrace reciprocal transparency. Apart from promoting openness and trust between citizens it would also enable citizens, who in these times are under constant surveillance by governments and corporations, to see and hold these institutions to task, consequently promoting a more honest and accountable society.

Apart from these political reasons, there is also the case to be made for what big data enables for personalisation. When Google or Amazon know your preferences, they in turn reduce search costs for you providing tailored recommendations and relevant advertising. Returning to Facebook, going back to its early days, Mark Zuckerberg himself said in 2010 that as people get more comfortable sharing their information with each other, privacy becomes less of a social norm. The crux of the position here is that a more open world leads to more empathy and understanding.

This position is not entirely without precedent either. In the 18th Century, Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher and jurist, conceptualised the Panopticon. This was essentially a circular prison where all prisoners could be observed without them knowing that they were being watched. This, however, was not simply a model of a prison but a blueprint for social progress. For Bentham, transparency was the ultimate tool for moral reformation. He believed that the uncertainty of being watched would lead people to self-regulate and behave virtuously.

Having cursorily traced the argument against privacy, we should mention possible objections. Here there is a historical precedent that is found in Cardinal Richelieu, a 17th century French statesman, who posited that: "If one would give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest man, I would find something in them to have him hanged." This position basically highlights that even innocent information can be weaponised or misinterpreted by those in power.

The most prominent modern figure to draw from this line of reasoning is Bruce Schneier, a cryptographer and privacy specialist. He argues that in reality, surveillance data is a distorted mirror. This is because states and corporations have specific agendas ranging from prosecution, profit, to social control. In other words, they don't look at your data to find the truth; they look at it to find a pattern that confirms their existing suspicions.

The central tragedy of the anti-privacy argument, whether in Plato’s Republic or Zuckerberg’s early Facebook, is that it assumes a benevolent or neutral observer. In reality, as Schneier notes, data is rarely neutral; it is a resource mined by those with the ability to interpret it. When the State or a corporation holds the keys to the Panopticon, transparency becomes a one-way street, where the citizen is exposed but the institution remains opaque.

In India, for instance, such manipulations are not without ready examples. An ongoing case which has the most clear parallels to such a logic is the Bhima Koregaon Elgar Parishad letters case (2018 - present). The prosecution here relied heavily on letters and documents found in the hard drives of activists Rona Wilson and Varavara Rao. These were, in turn, used to charge them under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, alleging that they were plotting against the State. Forensic analysis by Arsenal Consulting found that the incriminating lines were actually planted onto their devices by malware (either Pegasus or NetWire) months before their arrest. This highlights how the State can misuse its capabilities to incriminate honest men.

The writer is an independent journalist who is pursuing his PhD. The views are personal.

Peca is being used against lawyers, journalists and human rights defenders.

Usama Khilji

IF post-2016 were the years when Peca’s misuse against those exercising their right to freedom of speech and press freedom was tested, 2025 was the year when the gaps in the state’s ability to fully abuse the law were filled.

The amendments to Peca were made in an opaque manner and passed by parliament in January 2025 without any consultations, public debate, or even parliamentary debate. Those of us who managed to attend a hearing at a Senate committee were informed that the members had been told to vote for the amendment as it was, with no room for any changes. Senators said that the amended law would not be used against journalists, but like most promises this was also immediately broken as was clear from the intent behind the amendments.

The results of this opaque, undemocratic process have been damaging in terms of the kind of changes made to the law; how cases have been filed against lawyers, journalists, and activists; and the chilling effect this has had on citizens and the media alike.

Wide-ranging procedural and substantive changes in Peca have been highly damaging. The National Cybercrime Investigation Authority (NCCIA) was formed under the law, which is essentially a new name for the FIA’s cybercrime wing, the investigation authority under Peca since 2016. Only 15 reporting centres exist currently with an in-person reporting requirement, which serves as a significant barrier for people to register a complaint leading to a case under Peca. The 2025 amendment undid a December 2023 amendment to Peca that had permitted complaints under the law to be filed at any police station in Pakistan.

Moreover, the 2025 amendment changed the definition of a complainant to be any person “having substantial reasons to believe that the offence has been committed” in addition to the “victim”, which significantly expands the ability to file a case — from an aggrieved person to any third party. The other significant change is that now the complainant does not have to be a “natural person” but can be any organisation, including a government department. Another significant change in definition includes expanding “social media platform” to include “any person that owns, provides or manages online information system for provision of social media or social network service”, which expands the purview of the law to people administering online groups or channels as well.

Peca is being used against lawyers, journalists and human rights defenders.

The amendment further criminalises free speech in the country by introducing Section 26-A that stipulates punishment of three years in jail and/or Rs2 million fine for “false or fake information”, without defining what that entails. The amendment also makes Section 20, which was struck down by the Islamabad High Court in 2022 but continues to be used illegally, cognisable and non-bailable. These two sections are responsible for criminalising free speech on the internet in Pakistan at a time when over 90 countries have decriminalised defamation, something that the IHC tried doing.

In practice, the 2025 Peca amendment has given the state through the NCCIA a free hand to prosecute any person that is seen as critical of state policies. In a constitutional democratic republic, the consequences of this are disastrous. And any constitutional protections that may exist in theory have been blurred after the 27th Amendment where the role of the executive in the appointment of judges has been expanded, with their ability to transfer judges without oversight.

Several journalists have been called in, in 2025, by the NCCIA for inquiries under Peca related to their work. For instance, Farhan Mallick, the founder of independent media platform Raftar, was arrested in February 2025 under Peca charges. Hum News journalist Khalid Jamil was arrested in Islamabad in August 2025 under Peca. Muhammad Aslam from Vehari has a case under Peca for reporting on alleged corruption in a road project. Iftikhar Ul Hassan of Samaa news from Vehari also had a Peca case against him by the municipal authority for a social media post about actions by local administration against a housing society. Muhammad Akbar Notezai of this paper was sent prosecution notices by the FIA for a corruption investigation which the RSF and Freedom Network have highlighted as retaliation against investigative reporting. In July 2025, upon NCCIA’s request, an Islamabad court ordered the blocking of 27 YouTube channels of journalists for “anti-Pakistan” reporting, some of which were later suspended upon appeal.

Peca is also being used against lawyers and human rights defenders. For instance, in the case of human rights lawyers Imaan Mazari-Hazir and Hadi Ali Chattha, a Peca case filed by the NCCIA relates to seven tweets from the year 2021 posted by Imaan Mazari on matters of the law, human rights, and enforced disappearances in the country, and Chattha’s supposed crime is reposting these tweets. The Supreme Court had to step in to direct the lower courts in Islamabad to follow due process and procedure in the case where multiple hearings were being held on the same day, and witness statements being recorded in the absence of the accused. During cross-questioning, the NCCIA official stated that government officials are allowed to say the same things that the couple is being prosecuted for saying.

In such an environment, journalists and lawyers are being turned into heroes for simply doing their jobs as that itself has become an act of courage. A parliament that passes laws without deliberation, an executive that arrests its citizens for exercising their right to freedom of speech, and a judiciary that does not protect the rights of citizens that it functions for need a reminder of the notion of fundamental rights and justice.

It is unsustainable for a regime to carry on with such oppression in a diverse republic like Pakistan. It is fundamental that citizens be allowed to express their opinions with the safety of their institutions rather than be victimised them. For that, parliament must undo these draconian amendments and decriminalise defamation.

The writer is director of Bolo Bhi, an advocacy forum for digital rights.

X: @UsamaKhilji

Published in Dawn, January 2nd, 2026

No comments:

Post a Comment