Moral philosophy professor James Beattie of Marischal College accused David Hume of Eurocentric arrogance, ignorance and victim-blaming, writes Dr Robin Mills

By Robin Mills

Friday, 18th September 2020,

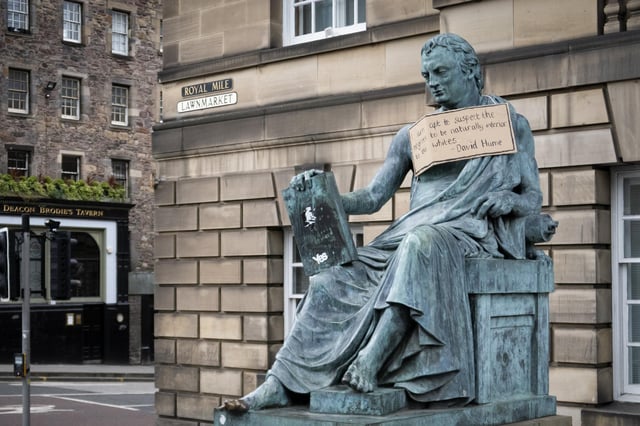

Racist remarks by the 18th-century philosopher David Hume have come under attack amid the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests, but he was also heavily criticised at the time (Picture: Jane Barlow/PA)

Edinburgh University has decided to remove philosopher David Hume’s name from its tower block at 40 George Square. The university claimed Hume’s views, while characteristic of his time, were abhorrent now and were causing some students distress. Were Hume’s racist beliefs commonplace? No doubt. But across late 18th-century western Europe, including Scotland, abolitionist movements were garnering popular support and informing political decision-making.

One widely disseminated passage was Beattie’s assault on Hume’s infamous footnote in which he claimed all non-white civilizations were intellectually inferior, and black Africans especially so. Beattie slung a barrage of arguments Hume’s way, accusing him of Eurocentric arrogance, ignorance of other civilisations, and failing to reflect critically on his own society’s problems. Beattie’s central challenge, however, was that Hume was blaming the victim. If African slaves did not demonstrate “ingenuity” or “genius”, this could hardly be said to be their fault.

Hume’s footnote was greedily deployed by pro-slavery campaigners. They used his fame – the footnote itself hardly counted as sustained argument – as evidence of the correctness of their cause. But Beattie’s refutation and celebrity were likewise used by abolitionists. The leading anti-slavery advocate of the 1770s, Granville Sharp, used Beattie’s attack in an influential campaign, fascinatingly described by modern historian David Olusoga. And throughout his anti-slavery activism, Beattie researched what he was talking about, whereas Hume hardly seemed to care.

Beattie was an activist professor of sorts. He ended his attack on Hume’s racism with a call to Britons to live up to their self-images as lovers of liberty and to fight to stop slavery.

Prompted by disgust at Hume’s opinions, Beattie lectured his students at Marischal College on slavery’s horrors and their need to act in humane and Christian ways to their fellow human. He organised petitions sent from Aberdeen during the height of abolitionist campaigning in 1788.

Edinburgh University has decided to remove philosopher David Hume’s name from its tower block at 40 George Square. The university claimed Hume’s views, while characteristic of his time, were abhorrent now and were causing some students distress. Were Hume’s racist beliefs commonplace? No doubt. But across late 18th-century western Europe, including Scotland, abolitionist movements were garnering popular support and informing political decision-making.

The most well-known contemporary critic of Hume’s racism was James Beattie, a moral philosophy professor at Marischal College Aberdeen from 1760 until 1797. Beattie was Hume’s bête noire. He shot to fame in 1770 with An Essay on Truth, a pugilistic takedown of Hume’s philosophical writings, which Beattie claimed denied the existence of all truth. The essay was one of the bestsellers of the Scottish Enlightenment.

One widely disseminated passage was Beattie’s assault on Hume’s infamous footnote in which he claimed all non-white civilizations were intellectually inferior, and black Africans especially so. Beattie slung a barrage of arguments Hume’s way, accusing him of Eurocentric arrogance, ignorance of other civilisations, and failing to reflect critically on his own society’s problems. Beattie’s central challenge, however, was that Hume was blaming the victim. If African slaves did not demonstrate “ingenuity” or “genius”, this could hardly be said to be their fault.

Hume’s footnote was greedily deployed by pro-slavery campaigners. They used his fame – the footnote itself hardly counted as sustained argument – as evidence of the correctness of their cause. But Beattie’s refutation and celebrity were likewise used by abolitionists. The leading anti-slavery advocate of the 1770s, Granville Sharp, used Beattie’s attack in an influential campaign, fascinatingly described by modern historian David Olusoga. And throughout his anti-slavery activism, Beattie researched what he was talking about, whereas Hume hardly seemed to care.

Beattie was an activist professor of sorts. He ended his attack on Hume’s racism with a call to Britons to live up to their self-images as lovers of liberty and to fight to stop slavery.

Prompted by disgust at Hume’s opinions, Beattie lectured his students at Marischal College on slavery’s horrors and their need to act in humane and Christian ways to their fellow human. He organised petitions sent from Aberdeen during the height of abolitionist campaigning in 1788.

Beattie compiled a book arguing against the slave trade and substantiating the claim, as he wrote to a friend in 1788, that slavery must cease “to clear the British character of a stain which is indeed of the blackest dye”. It was never published, but the crux of Beattie’s position appeared in a sustained attack on slavery in his student textbook Elements of Moral Science (1793). Here an impassioned Beattie described slavery as “utterly repugnant to every principle of reason, religion, humanity, and conscience”

The opposition of Hume and Beattie reflected the divisions within Scottish society over slavery. One event in Aberdeen epitomises this. In 1792 professors at Beattie’s employer Marischal College drew up another abolitionist petition to the British Government. The rival King’s College, by contrast, was studiously silent. Beattie noted with pleasure to William Wilberforce that Aberdeen’s town council had voted to send a petition to London.

Like many abolitionists, Beattie believed the campaign needed to be realistic about slavery’s end. Sudden cessation was a political impossibility given the slavery lobby’s clout. Likewise, one-off abolition would leave the wretched trade’s dehumanised victims without the means to survive. Nor was Beattie pushing for the abandonment of Britain’s colonies.

Beattie’s proposals will seem piecemeal, even immoral by our standards. Slavery, he thought, would wither away without major intervention if wage incentives and education were introduced. Education would bring slaves back up the level of dignified rational humans, which their oppression had denied to them. Granting freedom to the most productive slaves would encourage self-sufficiency and independence. It would demonstrate to plantation owners that it was more profitable to abandon the practice.

Beattie was part of an ongoing conversation within the Scottish abolition movement. He discussed slavery repeatedly with his old friend from student days in Aberdeen, James Ramsay. Ramsay was a naval surgeon turned Anglican priest who worked in St Kitts. Upon his return in the mid-1780s Ramsay campaigned fearlessly, despite vicious attacks, against the slavery he had witnessed first-hand. Beattie was not alone.

What does all of this tell us? Sure, Hume’s position was reprehensible to many contemporaries, like it is to our sensibilities. On racial issues at least, Beattie is a more amenable figure. Even then, many of his opinions will strike us as debatable, if not deplorable.

The study of the past, however, is not therapy. Viewing history as a storehouse of laudables and deplorables infantilises us. If we go to the past looking for ammunition for contemporary battles, we will fail to understand what has gone before. We apply our standards and get the answers we already wanted. We remain steadfast in our mindset and we do not learn anything.

While a tiny part of the story, thinking about Beattie’s and Hume’s attitudes helps us understand how slavery endured and how it ended. It is the sort of thing that universities should be encouraging, rather than seeking symbolic erasure of the uncomfortable past. This could be an opportunity for debate, nuance, and understanding. But if we approach the past as victims, we might get protection, but we will not get insight.

Dr Robin Mills is a Leverhulme early career fellow at Queen Mary University of London

David Hume was a brilliant philosopher but also a racist involved in slavery – Dr Felix Waldmann

David Hume advised his patron, Lord Hertford to buy a slave plantation, facilitated the deal and lent £400 to one of the principal investors. And when criticised for racism in 1770, he was unmoved, writes Dr Felix Waldmann

By Felix Waldmann

Friday, 17th July 2020, 7:30 am

A petition by a student of the University of Edinburgh has called for the re-naming of its David Hume Tower, drawing attention to the philosopher’s 1753 essay, Of National Characters, in which he voiced his suspicion that “negroes” are “naturally inferior to the whites”. These “racist epithets”, the petition notes, justify the removal of Hume’s name from the building. It has gathered 1,750 signatures.

As a historian who specialises in Hume’s life and works, I was not surprised to find Hume’s views discussed in the weeks after the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol. Hume’s own statue on the Royal Mile was recently targeted by a protestor, who fixed a placard to it bearing Hume’s notorious statement from Of National Characters.

As debate over Henry Dundas’s statue has grown in recent weeks, it was inevitable that the commemoration of Hume in Edinburgh would fall under suspicion.

There is no question that Hume was a brilliant philosopher, whose writings have shaped modern philosophy and Scottish culture. His Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40) may be the most significant work of philosophy published in English before the 20th century. His puckish scepticism about the existence of religious miracles played a significant part in defining the critical outlook which underpins the practice of modern science.

But his views served to reinforce the institution of racialised slavery in the later 18th century. More importantly, the fact that he was involved in the slave trade is now a matter of record, thanks to a discovery in Princeton University Library. It was there that I recently found an unknown letter of March 1766 by Hume, in which he encouraged his patron Lord Hertford to purchase a slave plantation in Grenada.

This is the only surviving evidence of Hume’s involvement in the slave trade, and it was completely unknown to scholars until I published it in my 2014 book Further Letters of David Hume.

Through additional archival research, I discovered that Hume had not only contacted Hertford; he had facilitated the purchase of the plantation by writing to the French Governor of Martinique, the Marquis d’Ennery, in June 1766. Indeed, he lent £400 to one of the principal investors earlier in the same year.

Hume denounced slavery – in ancient Rome

It did not surprise me that this information was omitted from the student’s petition, since it is known only to the specialist audience which read Further Letters of David Hume.

But it was a discovery which I expected would one day force scholars to re-evaluate their judgement of Hume, who was not otherwise known to have participated in the slave trade and who devoted a considerable part of an essay in 1748 denouncing the practice of slavery in ancient Rome.

Some may attribute Hume’s conduct in this affair to the social conventions of his time. Eighteenth-century Scotland was a racist society.

Many of its most prominent figures were direct beneficiaries of the slave trade. Scotland in general reaped the advantages of slavery in Britain’s colonies. It could be argued that holding Hume to the standard of a later age would be unfair. We should acknowledge, instead, that Hume could not criticise racism and slavery without upsetting social conventions.

But this argument is absurd. Hume was a genius by the standards of the 18th century. He was not deferential to convention. In fact, he was the antonym of convention. He was sufficiently wealthy in 1766 not to assist in this scheme. And he was aware of the widespread denunciation of slavery by his contemporaries, including in books by his friends and correspondents.

One of world’s most important philosophers

Anyone with Hume’s intelligence would recognise the enormity of slavery. But Hume sought to benefit from it. In Of National Characters, he justified it. When James Beattie of Aberdeen criticised Hume’s racist comments in 1770, Hume was unmoved. The last authorised edition of the essay, published in 1777, repeats the same sentiments, almost verbatim.

Where does this leave Hume’s reputation? The irony in his matter is that Hume was always an unlikely candidate for celebration by the University of Edinburgh. Although he studied at the University between about 1722 and 1725, the institution refused to employ him as a professor of moral philosophy in 1745 because of his religious scepticism, and it was this – in part – which prompted his departure from Edinburgh for four years.

It was only in the 20th century that Hume’s status as one of the university’s most eminent alumni was commemorated. This is because Hume was then, rightly, regarded as one of the most important philosophers ever to have lived. His works found an eager audience in an increasingly secularised society.

The posthumous celebration of Adam Smith’s legacy is similar. As Smith became an apostle of free-market capitalism, interest in his works grew. His face now appears on the £20 note in England and his statue accompanies Hume’s on the Royal Mile.

Wagner, a vicious anti-semite and brilliant composer

It is important, however, to distinguish between studying an individual and venerating him. As an observant Jew and fan of classical music, it pains me to admit that Richard Wagner – a vicious anti-semite – is one of the most important composers ever to have lived. His genius and influence are impossible to deny.

The question is whether this importance needs to be celebrated by the use of statues or the emblazoning of names on buildings. If I had to work in a building named after Wagner, or if I had to walk past a statue of the man, I would find it preposterous. But if you asked me to stop listening to his music, I would object. Listening to his music is a personal choice, which I would not impose upon others.

There are many questions to consider when removing a statue or expunging name from a building. As we have found with the debate over the Melville Monument, these questions are aesthetic, moral, and historical. In Hume’s case, the history and morality of the matter is clear: Hume was an unashamed racist, who was directly involved in the slave trade.

Dr Felix Waldmann is a Fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge. He was the David Hume Fellow at the University of Edinburgh in 2016.

David Hume advised his patron, Lord Hertford to buy a slave plantation, facilitated the deal and lent £400 to one of the principal investors. And when criticised for racism in 1770, he was unmoved, writes Dr Felix Waldmann

By Felix Waldmann

Friday, 17th July 2020, 7:30 am

A petition by a student of the University of Edinburgh has called for the re-naming of its David Hume Tower, drawing attention to the philosopher’s 1753 essay, Of National Characters, in which he voiced his suspicion that “negroes” are “naturally inferior to the whites”. These “racist epithets”, the petition notes, justify the removal of Hume’s name from the building. It has gathered 1,750 signatures.

As a historian who specialises in Hume’s life and works, I was not surprised to find Hume’s views discussed in the weeks after the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol. Hume’s own statue on the Royal Mile was recently targeted by a protestor, who fixed a placard to it bearing Hume’s notorious statement from Of National Characters.

As debate over Henry Dundas’s statue has grown in recent weeks, it was inevitable that the commemoration of Hume in Edinburgh would fall under suspicion.

There is no question that Hume was a brilliant philosopher, whose writings have shaped modern philosophy and Scottish culture. His Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40) may be the most significant work of philosophy published in English before the 20th century. His puckish scepticism about the existence of religious miracles played a significant part in defining the critical outlook which underpins the practice of modern science.

But his views served to reinforce the institution of racialised slavery in the later 18th century. More importantly, the fact that he was involved in the slave trade is now a matter of record, thanks to a discovery in Princeton University Library. It was there that I recently found an unknown letter of March 1766 by Hume, in which he encouraged his patron Lord Hertford to purchase a slave plantation in Grenada.

This is the only surviving evidence of Hume’s involvement in the slave trade, and it was completely unknown to scholars until I published it in my 2014 book Further Letters of David Hume.

Through additional archival research, I discovered that Hume had not only contacted Hertford; he had facilitated the purchase of the plantation by writing to the French Governor of Martinique, the Marquis d’Ennery, in June 1766. Indeed, he lent £400 to one of the principal investors earlier in the same year.

Hume denounced slavery – in ancient Rome

It did not surprise me that this information was omitted from the student’s petition, since it is known only to the specialist audience which read Further Letters of David Hume.

But it was a discovery which I expected would one day force scholars to re-evaluate their judgement of Hume, who was not otherwise known to have participated in the slave trade and who devoted a considerable part of an essay in 1748 denouncing the practice of slavery in ancient Rome.

Some may attribute Hume’s conduct in this affair to the social conventions of his time. Eighteenth-century Scotland was a racist society.

Many of its most prominent figures were direct beneficiaries of the slave trade. Scotland in general reaped the advantages of slavery in Britain’s colonies. It could be argued that holding Hume to the standard of a later age would be unfair. We should acknowledge, instead, that Hume could not criticise racism and slavery without upsetting social conventions.

But this argument is absurd. Hume was a genius by the standards of the 18th century. He was not deferential to convention. In fact, he was the antonym of convention. He was sufficiently wealthy in 1766 not to assist in this scheme. And he was aware of the widespread denunciation of slavery by his contemporaries, including in books by his friends and correspondents.

One of world’s most important philosophers

Anyone with Hume’s intelligence would recognise the enormity of slavery. But Hume sought to benefit from it. In Of National Characters, he justified it. When James Beattie of Aberdeen criticised Hume’s racist comments in 1770, Hume was unmoved. The last authorised edition of the essay, published in 1777, repeats the same sentiments, almost verbatim.

Where does this leave Hume’s reputation? The irony in his matter is that Hume was always an unlikely candidate for celebration by the University of Edinburgh. Although he studied at the University between about 1722 and 1725, the institution refused to employ him as a professor of moral philosophy in 1745 because of his religious scepticism, and it was this – in part – which prompted his departure from Edinburgh for four years.

It was only in the 20th century that Hume’s status as one of the university’s most eminent alumni was commemorated. This is because Hume was then, rightly, regarded as one of the most important philosophers ever to have lived. His works found an eager audience in an increasingly secularised society.

The posthumous celebration of Adam Smith’s legacy is similar. As Smith became an apostle of free-market capitalism, interest in his works grew. His face now appears on the £20 note in England and his statue accompanies Hume’s on the Royal Mile.

Wagner, a vicious anti-semite and brilliant composer

It is important, however, to distinguish between studying an individual and venerating him. As an observant Jew and fan of classical music, it pains me to admit that Richard Wagner – a vicious anti-semite – is one of the most important composers ever to have lived. His genius and influence are impossible to deny.

The question is whether this importance needs to be celebrated by the use of statues or the emblazoning of names on buildings. If I had to work in a building named after Wagner, or if I had to walk past a statue of the man, I would find it preposterous. But if you asked me to stop listening to his music, I would object. Listening to his music is a personal choice, which I would not impose upon others.

There are many questions to consider when removing a statue or expunging name from a building. As we have found with the debate over the Melville Monument, these questions are aesthetic, moral, and historical. In Hume’s case, the history and morality of the matter is clear: Hume was an unashamed racist, who was directly involved in the slave trade.

Dr Felix Waldmann is a Fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge. He was the David Hume Fellow at the University of Edinburgh in 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment