Holidaymakers were turned away, police checked on visitors and those caught flouting the restrictions faced fines and even imprisonment. This is not 2020 but ‘Lockdown 1940’ in the Highlands.

By Alison Campsie

Friday, 18th September 2020

UpdatedSaturday, 19th September 2020,

By Alison Campsie

Friday, 18th September 2020

UpdatedSaturday, 19th September 2020,

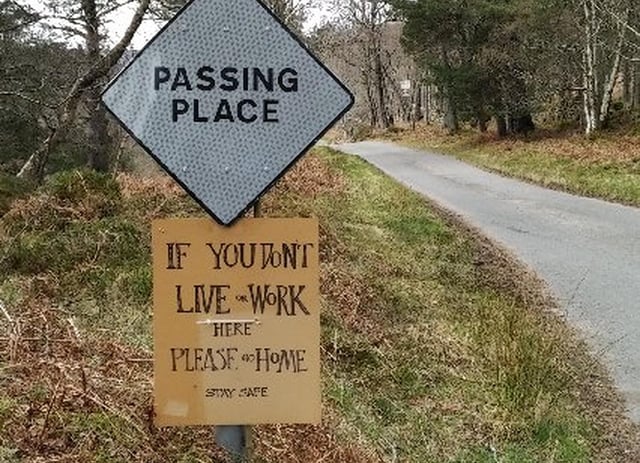

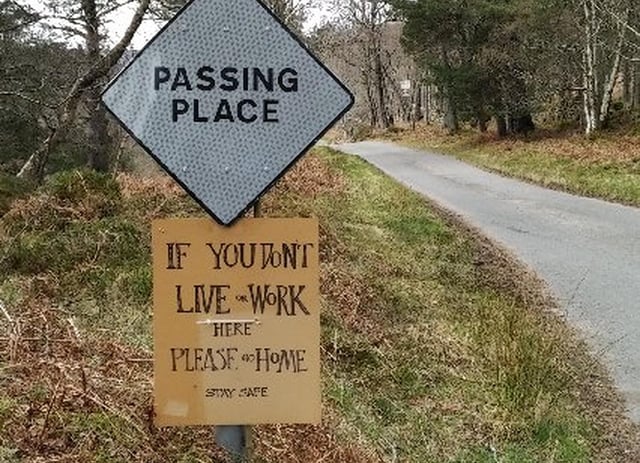

A sign at the Forest of Birse in Aberdeenshire which appeared in Spring 2020, warning visitors to stay away during the Covid-19 lockdown. Eighty years earlier, and restrictions were placed on the movement of thousands of people throughout the Highlands.

Eighty years ago and it was not a pandemic that restricted movement across 40 per cent of Scotland’s land mass, but the threat of invasion under World War Two.

Caithness , Sutherland , Ross and Cromarty and parts of the then counties of Inverness and Argyll were placed in a Protected Area by the War Office in March of that year in a bid to bid to safeguard the naval defences of the far north as well as prepare for the possibility of the enemy landing on Scotland’s shores

Queues formed around police stations by thousands of Highlanders seeking proof of residence documents that had to be pinned to their identity cards. Anyone who wanted to visit the area, whether it be on holiday or for some types of business – had to apply for a permit from either Edinburgh, Glasgow or the Passport Office in London.

Letters to newspapers complained about snags and delays in the system. Articles reported the fines given out to those found breaching the new regulations.

Checkpoints were placed throughout the north, with the army patrolling one main barrier built at Beauly.

Neil Bruce, of Banchory, a postgraduate of the history department at the University of Highlands and Islands, has researched the Protected Area introduced in 1940 and said the Highlands effectively became a "military controlled zone”. A similar scheme was introduced during World War One.

He said: “Restricting access in wartime resonates with 2020. What is striking is that in early 2020, communities really took matters much more into their own hands as restrictions were put in place. Communities felt they had to look after themselves. But in 1940, it was officialdom at work – with the help of the police and the military.”

Those who flouted the restrictions quickly ended up court as the 1940 Protected Area was enforced.

A Robert Michie was sentenced to a £2 fine or 10 days imprisonment at Inverness Sheriff Court for circumventing the army’s Beauly barrier which controlled the north road, research by Mr Bruce found.

Meanwhile, holidaymaker Jessie Macleod freely crossed the Beauly barrier several times before being found to be without permit. In her defence she said she believed her identification card was sufficient proof but it was not enough for her to escape a 10/- fine.

Meanwhile, John P. McGovern, a farm labourer in Caithness for 11 years, received more leniency. He was remanded in custody while Wick police obtained the necessary military permit.

Other reports detailed how one man was only allowed to attend his father’s funeral having “pulled certain very important wires which are not given to all men to reach”.

Mr Bruce said there were suspicions about preferential treatment being given in some cases, not least when Lord Redesdale and daughter Deborah Mitford holed up on the tiny island of Inch Kenneth, off Mull, which they bought just before the outbreak of war.

Secretary for War, Anthony Eden defended Redesdale’s ‘valid reason for finding it desirable and necessary to reside there during part of the year’ seeing no ‘reasonable grounds for disquiet throughout Scotland’.

Minister for Security and Home Secretary, Sir John Anderson, said the the island was ‘visited periodically by the police’, though he had no grounds ‘for prohibiting the present inhabitants from living there’.

Mr Bruce added: "In spring 2020, echoes reverberated when officials told citizens to stay at home, then ignored the same instruction. Elsewhere, police visited Lismore following concerns about a non-resident’s arrival.”

Meanwhile, residents from enemy countries required a specific permit and had to adhere to strict regulations, Mr Bruce said. Two Italian men, Enrico and Antonio Pizzamiglio, were fined £10, or the equivalent of around £560 at today’s values, for forgetting to report to their local police station before overnight curfew set in.

The restrictions created another issue familiar in 2020 – the struggle for tourism to survive in the Highlands.

Tourism was killed almost ‘stone dead’ in 1940 and the slow issue of visitor permits brought sparse Easter trade, research by Mr Bruce found.

A report in The Scotsman encouraged readers not to worry about food restrictions or petrol rationing, but warned that bed and breakfasts and other tourist businesses may be unable to continue under the restrictions.

Highlighted as particularly vulnerable were the small enterprises set up by the “Women of Ross”, from bed and breakfasts run out of lone shielings to overight accommodation offered above village shops.

Visitors with even the correct documents could find themselves stopped from boarding ferries or trains without warning with no compensation offered.

When Anthony Eden was pressed why some permit applications were refused. In his response, he said: “There may be reasons which I would rather not refer to in public.”

It it thought, however, they included an expected imminent invasion or the construction of defensive works to thwart the enemy.

As in 2020, the need for protection was ever real.

Eighty years ago and it was not a pandemic that restricted movement across 40 per cent of Scotland’s land mass, but the threat of invasion under World War Two.

Caithness , Sutherland , Ross and Cromarty and parts of the then counties of Inverness and Argyll were placed in a Protected Area by the War Office in March of that year in a bid to bid to safeguard the naval defences of the far north as well as prepare for the possibility of the enemy landing on Scotland’s shores

Queues formed around police stations by thousands of Highlanders seeking proof of residence documents that had to be pinned to their identity cards. Anyone who wanted to visit the area, whether it be on holiday or for some types of business – had to apply for a permit from either Edinburgh, Glasgow or the Passport Office in London.

Letters to newspapers complained about snags and delays in the system. Articles reported the fines given out to those found breaching the new regulations.

Checkpoints were placed throughout the north, with the army patrolling one main barrier built at Beauly.

Neil Bruce, of Banchory, a postgraduate of the history department at the University of Highlands and Islands, has researched the Protected Area introduced in 1940 and said the Highlands effectively became a "military controlled zone”. A similar scheme was introduced during World War One.

He said: “Restricting access in wartime resonates with 2020. What is striking is that in early 2020, communities really took matters much more into their own hands as restrictions were put in place. Communities felt they had to look after themselves. But in 1940, it was officialdom at work – with the help of the police and the military.”

Those who flouted the restrictions quickly ended up court as the 1940 Protected Area was enforced.

A Robert Michie was sentenced to a £2 fine or 10 days imprisonment at Inverness Sheriff Court for circumventing the army’s Beauly barrier which controlled the north road, research by Mr Bruce found.

Meanwhile, holidaymaker Jessie Macleod freely crossed the Beauly barrier several times before being found to be without permit. In her defence she said she believed her identification card was sufficient proof but it was not enough for her to escape a 10/- fine.

Meanwhile, John P. McGovern, a farm labourer in Caithness for 11 years, received more leniency. He was remanded in custody while Wick police obtained the necessary military permit.

Other reports detailed how one man was only allowed to attend his father’s funeral having “pulled certain very important wires which are not given to all men to reach”.

Mr Bruce said there were suspicions about preferential treatment being given in some cases, not least when Lord Redesdale and daughter Deborah Mitford holed up on the tiny island of Inch Kenneth, off Mull, which they bought just before the outbreak of war.

Secretary for War, Anthony Eden defended Redesdale’s ‘valid reason for finding it desirable and necessary to reside there during part of the year’ seeing no ‘reasonable grounds for disquiet throughout Scotland’.

Minister for Security and Home Secretary, Sir John Anderson, said the the island was ‘visited periodically by the police’, though he had no grounds ‘for prohibiting the present inhabitants from living there’.

Mr Bruce added: "In spring 2020, echoes reverberated when officials told citizens to stay at home, then ignored the same instruction. Elsewhere, police visited Lismore following concerns about a non-resident’s arrival.”

Meanwhile, residents from enemy countries required a specific permit and had to adhere to strict regulations, Mr Bruce said. Two Italian men, Enrico and Antonio Pizzamiglio, were fined £10, or the equivalent of around £560 at today’s values, for forgetting to report to their local police station before overnight curfew set in.

The restrictions created another issue familiar in 2020 – the struggle for tourism to survive in the Highlands.

Tourism was killed almost ‘stone dead’ in 1940 and the slow issue of visitor permits brought sparse Easter trade, research by Mr Bruce found.

A report in The Scotsman encouraged readers not to worry about food restrictions or petrol rationing, but warned that bed and breakfasts and other tourist businesses may be unable to continue under the restrictions.

Highlighted as particularly vulnerable were the small enterprises set up by the “Women of Ross”, from bed and breakfasts run out of lone shielings to overight accommodation offered above village shops.

Visitors with even the correct documents could find themselves stopped from boarding ferries or trains without warning with no compensation offered.

When Anthony Eden was pressed why some permit applications were refused. In his response, he said: “There may be reasons which I would rather not refer to in public.”

It it thought, however, they included an expected imminent invasion or the construction of defensive works to thwart the enemy.

As in 2020, the need for protection was ever real.

No comments:

Post a Comment