The wave of protests across the Arab world that began a decade ago will continue to be a long, uncertain and painful ordeal

Alain Gabon

1 January 2020

An Iraqi protester walks past graffiti in Baghdad on 20 December (AFP)

Applied to a region as volatile, combustible and uncertain as the Middle East and North Africa, the forecasting exercise is always tricky and risky. No analyst who specialised in the region saw the 2011 Arab Spring coming.

Those momentous events, which continue to structure the region both politically and symbolically, took everyone by surprise - including both local and foreign governments, as well as the demonstrators themselves, who often declared how they did not think anything like this could really happen.

Now, they know it can.

No return to the status quo

This new awareness of their own revolutionary or reformist capabilities - the knowledge that they can exist as powerful non-state actors capable of toppling even the most apparently stable regimes, such as Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt or Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s Tunisia - will remain a major factor in the years and decades to come.

In a region where the “Arab street” never had any real say, and where the political order was always determined by forces well beyond their control, including powerful imperialist foreign governments, it is no exaggeration to liken the 2011 Arab Spring and its continuing aftermath to the 1789 French Revolution. Such a momentous change cannot be erased, no matter how hard repressive regimes and their Western or Russian backers - which typically support them unconditionally, regardless of the atrocities they commit - will try.

They will cling to their privilege at any cost, including brutal police and military repression, and massacres of their own populations

In 2020, as in the preceding, restless two years, there will be no return to the old status quo, because people - especially younger generations - have now become agents of history, fully aware of themselves as a force for change.

Besides this recent Arab awakening, persistent structural conditions, including stagnant, sluggish or regressive economies; declining living standards among large segments of MENA populations, including the educated middle class; and repressive governments, will continue to make genuine human development impossible, denying these populations a true place as full citizens in their own countries. These factors will continue to fuel the new culture of protest and dissent.

Contrary dynamics

These countries will remain dominated by the conflict that for years has pitted against each other - in a direct, frontal and often violent clash - two antagonistic, uncompromising and irreconcilable forces: the dynamic of popular democratisation through never-ending waves of mass protest, and the contrary dynamic of autocratic restoration.

The latter is best exemplified by the post-2011 rise of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt, the surprising comeback of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, the autocratic turn of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, or the new assertiveness of the Saudi and Emirati regimes.

Those regimes, backed by Western allies who have chosen to remain firmly on the side of the oppressors - and Israel, of course, should be on that list - will fight tooth and nail “until the last Syrian” (or Iraqi, or Lebanese, or Algerian) to preserve whatever they can of the old, obsolete status quo. They will cling to their privilege at any cost, including brutal police and military repression, and massacres of their own populations.

In the least violent cases, such as Lebanon or Algeria, the powers-that-be will offer a few minor or cosmetic reforms, such as changing a prime minister or president, in hopes of appeasing protesters. But given the new political culture and historical awareness that has taken root, especially among the young, globalised generations, this will not work.

There is no returning to the old status quo. The Arab revival will continue to be a long, uncertain and painful ordeal, well beyond 2020.

What is certain is that the process will continue, in particular because of the new culture of political protest and pro-democracy activism, coupled with an admirable absence of fear on the part of the younger generations, even in the face of the worst forms of regime violence and repression. They have seen and experienced it for years now, in Syria, Egypt and elsewhere - and yet they still take to the streets.

Regional geopolitical forces

Geopolitically, there are a few more things that can be relatively safely predicted, despite the looming question of whether US President Donald Trump will remain in office beyond 2020.

Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Israel will remain the most powerful regional hegemons, while the Egyptian, Syrian and Algerian regimes will remain reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces of stagnation or regression, stubbornly standing in the way of democratisation and human development.

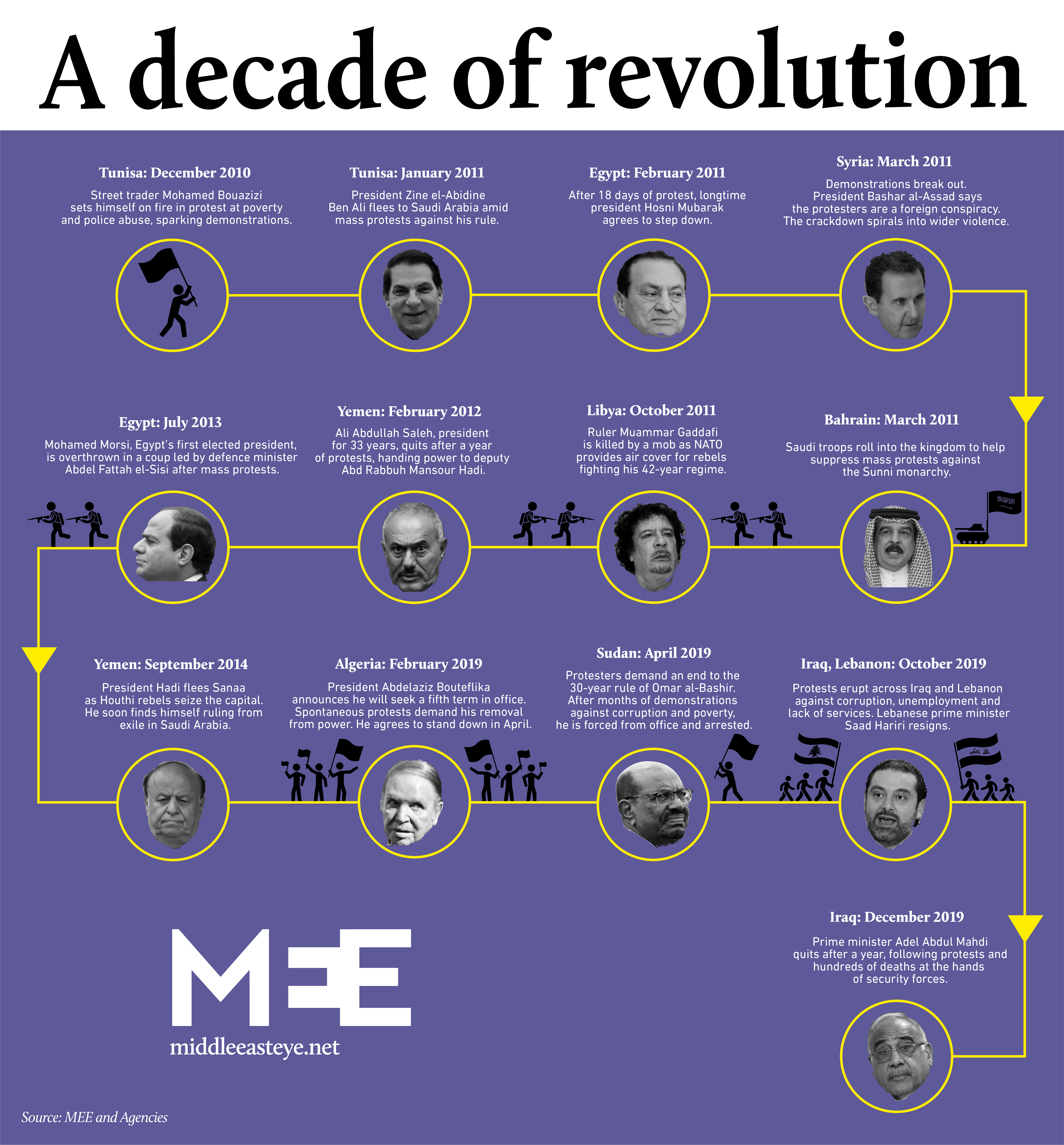

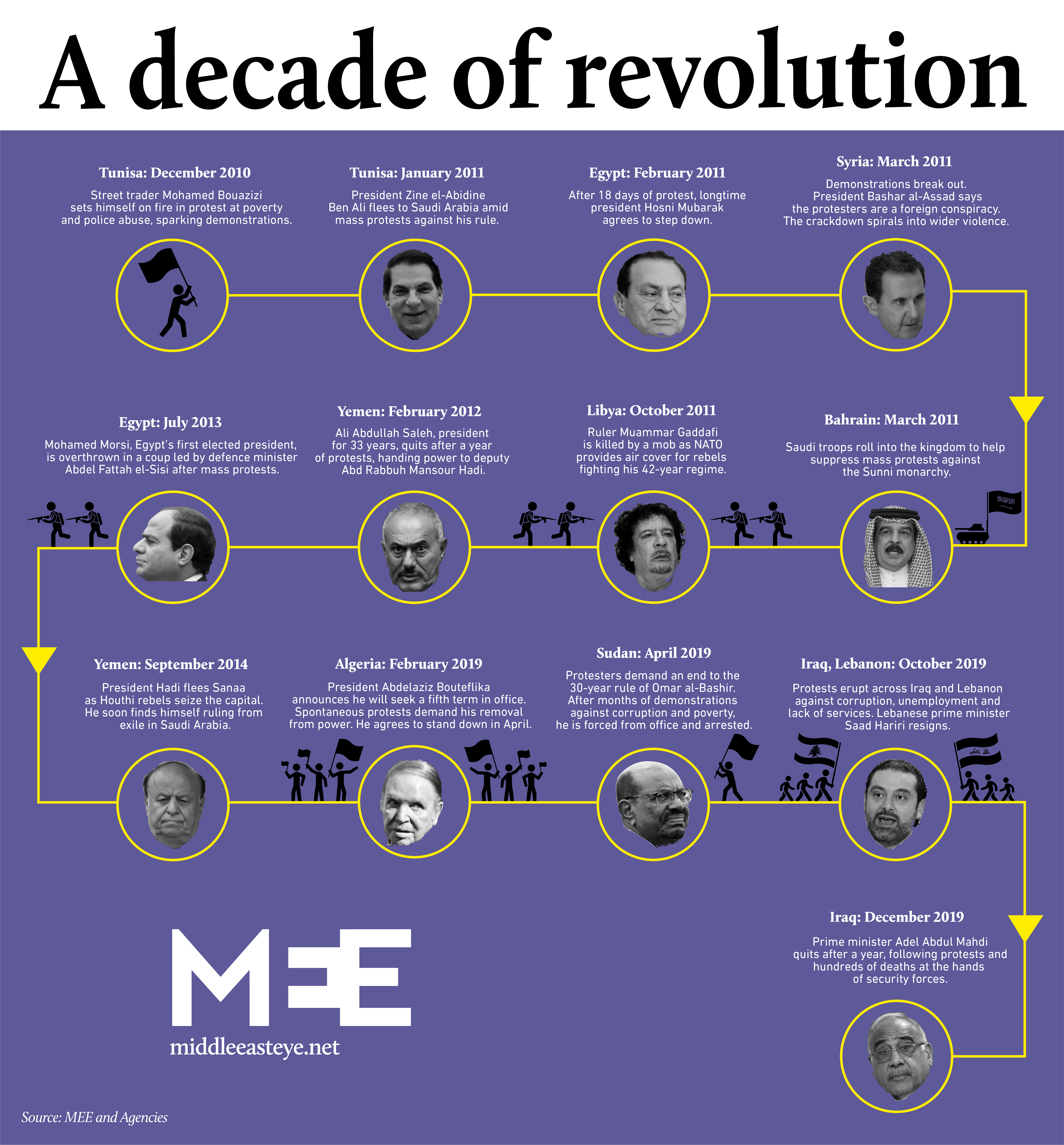

2010-2019: The Middle East's decade of revolutionRead More »

Syria under Assad will continue the surprising comeback on the regional and world stage that it started this year. It is likely that Assad himself, who committed war crimes, will be increasingly recognised again as Syria’s sole and legitimate president for pragmatic reasons; everybody, even foes such as Turkey, the US and the EU, now understand he is apparently invincible and will not be removed.

Despite its domestic political problems, Israel, now fully a right-wing, nationalist ethno-state of the worst kind, will continue its colonialist policies, including the annexation of Palestinian land through settlements and oppression of Palestinians. This is likely to continue with complete impunity and the continuing support of the US, whether Trump is reelected or not; and with the cowardly silence and passive complicity of the EU and other Arab states, notably Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia and Sisi’s Egypt.

The brave Tunisia will pursue its relatively lonely democratic journey, despite an awful economic situation and little help from Western and other Arab states, while flareups will continue in Iraq and Lebanon, which have witnessed two of the most active pro-democracy uprisings of the past two years.

De-escalation of armed conflicts

One can also make the daring bet that two of the worst, most violent conflicts of the past several years, in Syria and Yemen, will be scaled back substantially and possibly move towards a resolution. We are already seeing various diplomatic initiatives, notably the agreement between Russia and Turkey to create a buffer zone in northeastern Syria.

The determining factor for a possible resolution in Syria is the military victory on the ground by Assad’s forces, backed by their Russian and Iranian allies.

Sadly, the fates of the two stateless peoples of the region, Palestinians and Kurds, will not improve and are likely to get even worse

In Yemen, it is the utter failure of Saudi Arabia’s aggression and the mounting pressure from its allies, including the US, to stop this horrible and useless war. The costs of the war amid serious economic and social issues at home, including youth unemployment and declining standards of living, could also push Riyadh to finally pull out.

Sadly, the fates of the two stateless peoples of the region, Palestinians and Kurds, will not improve and are likely to get even worse - especially for Palestinians, now that they have been openly abandoned by the US and EU, and have become an obvious embarrassment for Arab regimes, several of which (including Saudi Arabia and Egypt) have switched to Israel’s side.

Mounting domestic turmoil

On a more optimistic note, despite alarmist talk about a possible major regional or international military conflagration (Israel-Iran, US-Russia, etc), that remains unlikely. The main reason is that all the major actors - Israel, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US - are fully aware they would have little to gain, but a lot to lose. So far, they have carefully calibrated their military operations to avoid a major escalation that could lead to an all-out war.

Turkey’s offensive in northern Syria, limited in geographic scope, duration and number of civilian casualties, is a good recent example. Meanwhile, Israel has resisted the temptation to reinvade Lebanon to target Hezbollah, while its strikes against Syria and Iran have also been limited.

1 January 2020

An Iraqi protester walks past graffiti in Baghdad on 20 December (AFP)

Applied to a region as volatile, combustible and uncertain as the Middle East and North Africa, the forecasting exercise is always tricky and risky. No analyst who specialised in the region saw the 2011 Arab Spring coming.

Those momentous events, which continue to structure the region both politically and symbolically, took everyone by surprise - including both local and foreign governments, as well as the demonstrators themselves, who often declared how they did not think anything like this could really happen.

Now, they know it can.

No return to the status quo

This new awareness of their own revolutionary or reformist capabilities - the knowledge that they can exist as powerful non-state actors capable of toppling even the most apparently stable regimes, such as Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt or Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s Tunisia - will remain a major factor in the years and decades to come.

In a region where the “Arab street” never had any real say, and where the political order was always determined by forces well beyond their control, including powerful imperialist foreign governments, it is no exaggeration to liken the 2011 Arab Spring and its continuing aftermath to the 1789 French Revolution. Such a momentous change cannot be erased, no matter how hard repressive regimes and their Western or Russian backers - which typically support them unconditionally, regardless of the atrocities they commit - will try.

They will cling to their privilege at any cost, including brutal police and military repression, and massacres of their own populations

In 2020, as in the preceding, restless two years, there will be no return to the old status quo, because people - especially younger generations - have now become agents of history, fully aware of themselves as a force for change.

Besides this recent Arab awakening, persistent structural conditions, including stagnant, sluggish or regressive economies; declining living standards among large segments of MENA populations, including the educated middle class; and repressive governments, will continue to make genuine human development impossible, denying these populations a true place as full citizens in their own countries. These factors will continue to fuel the new culture of protest and dissent.

Contrary dynamics

These countries will remain dominated by the conflict that for years has pitted against each other - in a direct, frontal and often violent clash - two antagonistic, uncompromising and irreconcilable forces: the dynamic of popular democratisation through never-ending waves of mass protest, and the contrary dynamic of autocratic restoration.

The latter is best exemplified by the post-2011 rise of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt, the surprising comeback of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, the autocratic turn of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, or the new assertiveness of the Saudi and Emirati regimes.

Those regimes, backed by Western allies who have chosen to remain firmly on the side of the oppressors - and Israel, of course, should be on that list - will fight tooth and nail “until the last Syrian” (or Iraqi, or Lebanese, or Algerian) to preserve whatever they can of the old, obsolete status quo. They will cling to their privilege at any cost, including brutal police and military repression, and massacres of their own populations.

In the least violent cases, such as Lebanon or Algeria, the powers-that-be will offer a few minor or cosmetic reforms, such as changing a prime minister or president, in hopes of appeasing protesters. But given the new political culture and historical awareness that has taken root, especially among the young, globalised generations, this will not work.

There is no returning to the old status quo. The Arab revival will continue to be a long, uncertain and painful ordeal, well beyond 2020.

What is certain is that the process will continue, in particular because of the new culture of political protest and pro-democracy activism, coupled with an admirable absence of fear on the part of the younger generations, even in the face of the worst forms of regime violence and repression. They have seen and experienced it for years now, in Syria, Egypt and elsewhere - and yet they still take to the streets.

Regional geopolitical forces

Geopolitically, there are a few more things that can be relatively safely predicted, despite the looming question of whether US President Donald Trump will remain in office beyond 2020.

Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Israel will remain the most powerful regional hegemons, while the Egyptian, Syrian and Algerian regimes will remain reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces of stagnation or regression, stubbornly standing in the way of democratisation and human development.

2010-2019: The Middle East's decade of revolutionRead More »

Syria under Assad will continue the surprising comeback on the regional and world stage that it started this year. It is likely that Assad himself, who committed war crimes, will be increasingly recognised again as Syria’s sole and legitimate president for pragmatic reasons; everybody, even foes such as Turkey, the US and the EU, now understand he is apparently invincible and will not be removed.

Despite its domestic political problems, Israel, now fully a right-wing, nationalist ethno-state of the worst kind, will continue its colonialist policies, including the annexation of Palestinian land through settlements and oppression of Palestinians. This is likely to continue with complete impunity and the continuing support of the US, whether Trump is reelected or not; and with the cowardly silence and passive complicity of the EU and other Arab states, notably Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia and Sisi’s Egypt.

The brave Tunisia will pursue its relatively lonely democratic journey, despite an awful economic situation and little help from Western and other Arab states, while flareups will continue in Iraq and Lebanon, which have witnessed two of the most active pro-democracy uprisings of the past two years.

De-escalation of armed conflicts

One can also make the daring bet that two of the worst, most violent conflicts of the past several years, in Syria and Yemen, will be scaled back substantially and possibly move towards a resolution. We are already seeing various diplomatic initiatives, notably the agreement between Russia and Turkey to create a buffer zone in northeastern Syria.

The determining factor for a possible resolution in Syria is the military victory on the ground by Assad’s forces, backed by their Russian and Iranian allies.

Sadly, the fates of the two stateless peoples of the region, Palestinians and Kurds, will not improve and are likely to get even worse

In Yemen, it is the utter failure of Saudi Arabia’s aggression and the mounting pressure from its allies, including the US, to stop this horrible and useless war. The costs of the war amid serious economic and social issues at home, including youth unemployment and declining standards of living, could also push Riyadh to finally pull out.

Sadly, the fates of the two stateless peoples of the region, Palestinians and Kurds, will not improve and are likely to get even worse - especially for Palestinians, now that they have been openly abandoned by the US and EU, and have become an obvious embarrassment for Arab regimes, several of which (including Saudi Arabia and Egypt) have switched to Israel’s side.

Mounting domestic turmoil

On a more optimistic note, despite alarmist talk about a possible major regional or international military conflagration (Israel-Iran, US-Russia, etc), that remains unlikely. The main reason is that all the major actors - Israel, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US - are fully aware they would have little to gain, but a lot to lose. So far, they have carefully calibrated their military operations to avoid a major escalation that could lead to an all-out war.

Turkey’s offensive in northern Syria, limited in geographic scope, duration and number of civilian casualties, is a good recent example. Meanwhile, Israel has resisted the temptation to reinvade Lebanon to target Hezbollah, while its strikes against Syria and Iran have also been limited.

Lebanese protesters set an Israeli flag ablaze during demonstrations on 21 October in Beirut (AFP)

The US has learned its Iraq lesson the hard way, and Trump, despite his bravado and military threats against Iran and Turkey, has not started a new war - unlike his predecessors. His non-interventionist, withdrawal policy is also very much congruent with that of the Obama administration.

Indeed, there is much more policy continuity between Trump and former President Barack Obama than analysts and media have been willing to acknowledge. Militarily, Trump has been even more moderate than Obama, who not only took drone killings, assassinations, and transnational secret forces operations to a whole new level, but also foolishly - though reluctantly - dragged the US into the Sarkozy-led NATO adventure in Libya, with the consequences including the destruction of that state, reminiscent of Iraq in 2003.

At least Trump has done nothing of that kind, and has often proven to be less hawkish than the Democrats, including the neocon Hillary Clinton and his own political-military establishment, which has been roasting him for pulling out of Syria.

Multiple fault lines

As the new decade begins, the region will remain riven by multiple faultlines, power plays for regional or religious domination, and intersecting conflicts, by which even a minor local conflict can quickly acquires a regional - and then international - dimension, sucking in multiple foreign powers to prolong the conflict and make it even more deadly, as we have seen in Yemen.

As a new decade begins, the region will continue to be a major playground for regional and international power plays

Similarly, in Syria, what started as a domestic civil war between Assad and his opposition quickly took on a regional and international dimension, sucking in Russia, the US, Turkey, Iran, Israel, the EU and more. The same is true of Libya, which has seen interventions of various types by Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the UAE, Russia and the US.

Alas, there is no reason to believe those specificities of the Middle East will somehow cease to produce their debilitating and violent effects. As a new decade begins, the region will continue to be a major playground for regional and international power plays, hegemonic competition and proxy wars.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

The US has learned its Iraq lesson the hard way, and Trump, despite his bravado and military threats against Iran and Turkey, has not started a new war - unlike his predecessors. His non-interventionist, withdrawal policy is also very much congruent with that of the Obama administration.

Indeed, there is much more policy continuity between Trump and former President Barack Obama than analysts and media have been willing to acknowledge. Militarily, Trump has been even more moderate than Obama, who not only took drone killings, assassinations, and transnational secret forces operations to a whole new level, but also foolishly - though reluctantly - dragged the US into the Sarkozy-led NATO adventure in Libya, with the consequences including the destruction of that state, reminiscent of Iraq in 2003.

At least Trump has done nothing of that kind, and has often proven to be less hawkish than the Democrats, including the neocon Hillary Clinton and his own political-military establishment, which has been roasting him for pulling out of Syria.

Multiple fault lines

As the new decade begins, the region will remain riven by multiple faultlines, power plays for regional or religious domination, and intersecting conflicts, by which even a minor local conflict can quickly acquires a regional - and then international - dimension, sucking in multiple foreign powers to prolong the conflict and make it even more deadly, as we have seen in Yemen.

As a new decade begins, the region will continue to be a major playground for regional and international power plays

Similarly, in Syria, what started as a domestic civil war between Assad and his opposition quickly took on a regional and international dimension, sucking in Russia, the US, Turkey, Iran, Israel, the EU and more. The same is true of Libya, which has seen interventions of various types by Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the UAE, Russia and the US.

Alas, there is no reason to believe those specificities of the Middle East will somehow cease to produce their debilitating and violent effects. As a new decade begins, the region will continue to be a major playground for regional and international power plays, hegemonic competition and proxy wars.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Alain Gabon

Dr. Alain Gabon is Associate Professor of French Studies and Chair of the Department of Foreign Languages & Literatures at Virginia Wesleyan University in Virginia Beach, USA. He has written and lectured widely in the US, Europe and beyond on contemporary French culture, politics, literature and the arts and more recently on Islam and Muslims. His works have been published in several countries in academic journals, think tanks, and mainstream and specialized media such as Saphirnews, Milestones. Commentaries on the Islamic World, and Les Cahiers de l'Islam. His recent essay entitled “The Twin Myths of the Western ‘Jihadist Threat’ and ‘Islamic Radicalisation ‘” is available in French and English on the site of the UK Cordoba Foundation.

Cardiology resident Alexandra Crooks and cardiologist Anna Gelzer of the School of Veterinary Medicine headed up care for 9-year-old Sophie, the beloved pet of Karen Cortellino, pictured here with her son Alex Peña. Not long after the ablation procedure, Cortellino says the boxer was “back to her perky self.” (Image: John Donges/Penn Vet)

Cardiology resident Alexandra Crooks and cardiologist Anna Gelzer of the School of Veterinary Medicine headed up care for 9-year-old Sophie, the beloved pet of Karen Cortellino, pictured here with her son Alex Peña. Not long after the ablation procedure, Cortellino says the boxer was “back to her perky self.” (Image: John Donges/Penn Vet) Sophie’s diagnosis of ARVC meant she could suffer a life-threatening arrhythmia, despite starting medications to reduce that risk. (Image: John Donges/Penn Vet)

Sophie’s diagnosis of ARVC meant she could suffer a life-threatening arrhythmia, despite starting medications to reduce that risk. (Image: John Donges/Penn Vet) Performing the mapping of Sophie’s heart and the ablation procedure was a team effort, involving experts from both the School of Veterinary Medicine and the Perelman School of Medicine. “I think the openness and enthusiasm for this type of multidisciplinary collaboration is a major strength of this University,” says Cory Tschabrunn (to right of Sophie, with black glasses around neck), who directs the translational electrophysiology lab where it happened. (Image: Anna Gelzer)

Performing the mapping of Sophie’s heart and the ablation procedure was a team effort, involving experts from both the School of Veterinary Medicine and the Perelman School of Medicine. “I think the openness and enthusiasm for this type of multidisciplinary collaboration is a major strength of this University,” says Cory Tschabrunn (to right of Sophie, with black glasses around neck), who directs the translational electrophysiology lab where it happened. (Image: Anna Gelzer) The technology Tschabrunn and Gelzer and colleagues used during the procedure mirrors that employed during a human intervention. At right, a map of Sophie’s heart guided the clinicians in making tiny burns to eliminate damaged heart tissue. (Image: Eva Larouche-Lebel)

The technology Tschabrunn and Gelzer and colleagues used during the procedure mirrors that employed during a human intervention. At right, a map of Sophie’s heart guided the clinicians in making tiny burns to eliminate damaged heart tissue. (Image: Eva Larouche-Lebel) From Sophie’s case and others that follow, researchers hope to glean information that could benefit both human and veterinary patients in the future. (Image: Alexandra Crooks)

From Sophie’s case and others that follow, researchers hope to glean information that could benefit both human and veterinary patients in the future. (Image: Alexandra Crooks)