ARMENIA

Time for Straight Talk: Are we chronic victims or do we have a vision?

The 30 years of Armenian independence have been at best bittersweet for the global Armenian nation. The euphoria of sovereignty was short lived as the geopolitical reality of Turkish aggression was immediately highlighted with the Artsakh liberation struggle. The windows of freedom for Armenians have been limited and unpredictable. Who would have forecast the First Republic in the vacuum of a concluding WWI during the Genocide? Incredibly, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent emergence of the Republic of Armenia were a liberation struggle with the withdrawal of the occupying forces. For a people with limited opportunities, the timing of these events was not optimal as the readiness for governing as a free state became less than perfect. The First Republic was plagued by the impact of the genocide, famine and resurgent aggressors. The current republic was unprepared for the market economy transition and resulted in migration, poverty and leadership. One of the unfortunate byproducts of a nation in almost a constant state of oppression is the emergence of a victim mentality in the core of our thinking. Some of the classic attributes are blaming others for our shortcomings, a lack of vision due to a survival mentality, an overdependence on others and a subordination of our thinking. If this sounds familiar, it is because it describes the rollercoaster of the last 30 years.

One lesson we have to learn if we are to grow as a nation is to look inward for the answers to our problems. Often we articulate the symptom, but not the cause. An example of this is our frustration with the lack of international support during the recent Artsakh War. It feels good (for about 10 seconds) to blame others, but the cause was really our inability to build a world class diplomatic network that cultivated our interests, military parity and acceptable compromises that protected Armenia/Artsakh while avoiding wars that we cannot win. The pain of the 44-day war was compounded by the depressing “blame game” that has followed, but none of these factions are truly willing to advocate for the changes required to solve these problems. We are truly at a crossroads. The victim bandwagon has taken us to the edge of the cliff. There are only two choices: continue to focus on excuses that will only delay our redemption or use this moment to embrace a new vision aligned with a prosperous future. As a hopeless optimist, I believe that moments of adversity are opportunities for growth. Most of our learning takes place when the challenges are the greatest. The dark clouds can sometimes produce life giving rain. In the depths of our current despair, we can also discover not just a silver lining but a gold vein. After 30 years of manipulation, subordination and estrangement, it is time to build a vision that embraces the entire global Armenian nation.

Prior to 1915, our nation and indigenous population on historic lands were essentially the same. There were Armenians living outside the homeland, but it was either considered temporary or was not organized into what we call today a diaspora. The crime of genocide committed by the Turkish government changed that definition.

The first several years of independence in the nineties were euphoric despite the transitional hardships. Our dream of an independent Armenia had been achieved in our lifetime. I subscribe to the vision that Armenia, whether on the current territory or on all of our historical lands, is a home to all Armenians. It is a place where all Armenians around the world and those living in the sovereign state can find identity. It is our answer to the unnatural state created by the Genocide when our people became separated from much of their historical land and became a majority dispersed people. Our recovery was quickly subordinated by our old enemy: not the Turks, but our craving for division. In the past, we were fueled by Ramgavar, Hunchag or Tashnagtsagan. The modern version became those from the diaspora (spyurk) or those living in the newly independent state. Other conflicts arose between the oligarchs who inherited the economic and political legacy of the former Soviet republic. After decades of survival and victim behavior, it seems our vision is simply to exist…nothing more, nothing less.

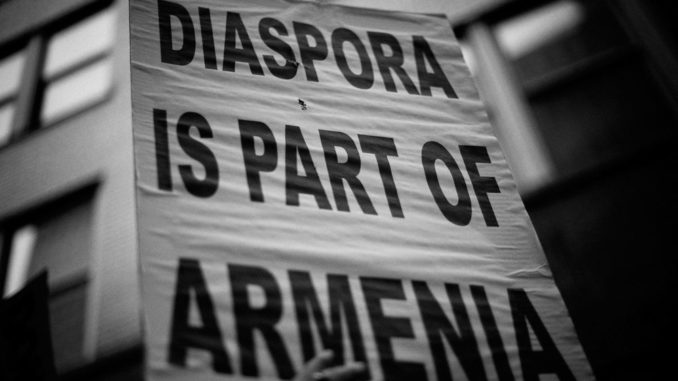

It’s obviously not quite as binary as that, as there are thousands in the diaspora and Armenia who have a greater vision for the homeland. The challenge remains whether they have the will and power to prevail. It is both amazing and frustrating that the diaspora and Armenia have been unable to unite in a collaboration of mutual need. How long can Armenia survive without the full capability of the diaspora, and how long can the diaspora remain vibrant with a fulfilling relationship with the homeland? We tease ourselves with rhetoric and pseudo visions when we are in crisis, only to recede to previous behavior when the “event” subsides. Our Catholicoi, for example, came “together” in 2015 and shared Holy Communion with all the people, yet have continued the power struggles to this day. During the Artsakh War, millions of dollars were raised in days to support our people in need. Shortly thereafter, the mistrust and accountability issues became the dominant theme. Pashinyan promised a free and open society, but has fallen into the political trappings of governing. I feel the diaspora taking a small step back and pondering the current chaos to determine whether their “investment” is appropriate. The problem lies in the lack of a unifying vision. You cannot expect the diasporan community to be all in when they are structurally outsiders. On the other hand, one cannot expect the people of Armenia to have their country run by diaspora remote control. The absence of trust and a unifying vision enables the extreme perceptions to become a reality. The one common thread is that these examples are not from external enemies; they are self-inflicted. Our only future is to build a unifying vision that all Armenians can identify with regardless of where they reside.

In order for Armenia to truly become the center of the global Armenian nation, we must all embrace change to create a new paradigm. Armenia’s laws should be amended to encourage repatriation, government service and most importantly erase the limitations. The trend in Armenian legislation over the last 25 years has been to liberalize the dual citizen requirements and rights, but there are still significant residency requirements for elected service. The issue is complex, but the main goal should be to give the homeland full access to the incredible talent base of the diaspora. It matters little if the constraint is a constitutional limitation, a legislative amendment or a reflection of behavioral bias. All the walls should be removed. If Armenia is the “homeland,” then it should be as welcoming as a home. Concerns about national security and loyalty can be resolved through normal vetting processes that should be applied equally to all who serve. Our achilles of mistrust must be surgically repaired. This matter has been debated and argued by distinguished legal and constitutional minds. The solution should be judged on its ability to bring the best resources to bear from the global Armenian nation. One of the great tragedies to date has been our collective inability to bring the national security, scientific, legal, economic, diplomatic and intelligence resources from around the globe into the republic. Armenians are renowned in every nation for their work ethic, resourcefulness and success in virtually every field known to mankind. In addition, generally Armenians are patriotic and care deeply about their heritage. It makes absolutely no sense that we are struggling to integrate our nation. Half of the equation of change is for the Armenian government and economic infrastructure to create more of a “pull” mentality. If Armenia begins behaving as the sacred gatekeeper of the 4,000+ year-old civilization, we can make remarkable progress and begin to erase our victim legacy of the Genocide.

The diaspora has an equal responsibility to make the marriage successful and eternal. If we wish to speak of the engagement of the “diaspora” with the homeland in a manner other than the presence of hundreds of nonprofits, NGOs and individuals investors, then we should make serious efforts to consolidate the communication and decision-making mechanisms to facilitate not only investing in the homeland but to make the best resources of the diaspora available. This will not be a popular notion as it connects to our eternal weakness: subordinating ourselves to a greater goal. It does not require a loss of identity but rather a mechanism to optimize the diaspora with the homeland. There has been occasional dialogue about a diaspora council or organization. I would advocate more of a confederation to channel and communicate effectively with the republic. The absence of sustained communication between parties has hampered progress. As citizens of the diaspora, we need to acknowledge this as a challenge that must be addressed. Any concerns in Armenia/Artsakh about a diaspora control can be easily quelled with an acknowledgement that rights and obligation must be balanced. There should be a tiered approach to the rights of those in the diaspora with residency and citizenship at the higher end. It is critical, however, that “rights” start with your heritage and continue from that point. This is the common denominator that all Armenians should be given to the homeland—a welcome mat that is constitutionally and legislatively based that will open the flow of participation in the life of Armenia/Artsakh, increase service in the government and mend the fabric torn apart by the Genocide. When we live a vision that all Armenians can identify with, we will be building not only a secure nation but a sustainable civilization. Our leaders both in the diaspora and Armenia can start with defining a common vision.

No comments:

Post a Comment