Myanmar polls open amid civil war, junta-backed party tipped to win

Button LabelListen

By Reuters

Button LabelListen

By Reuters

Dec 28, 2025

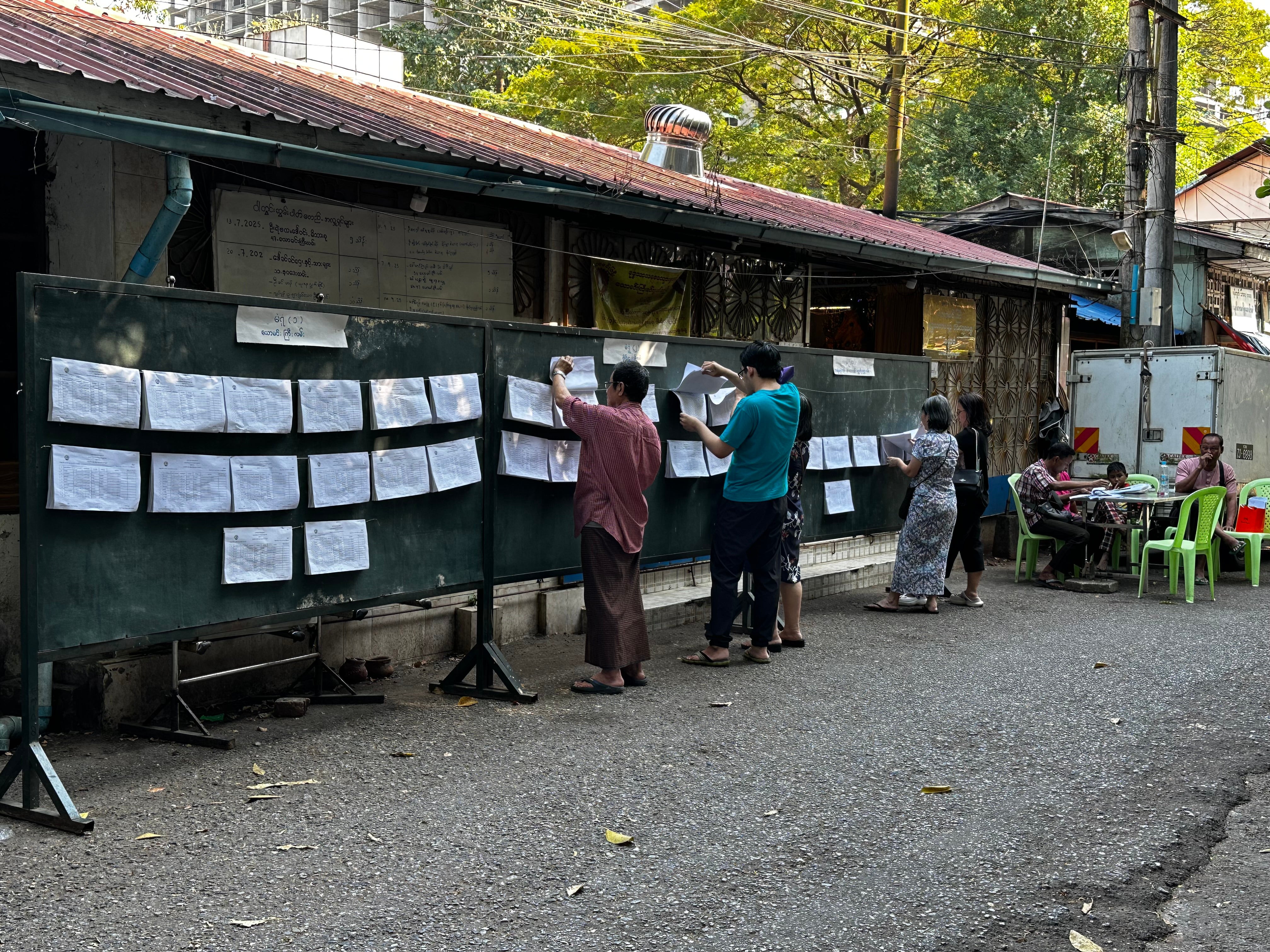

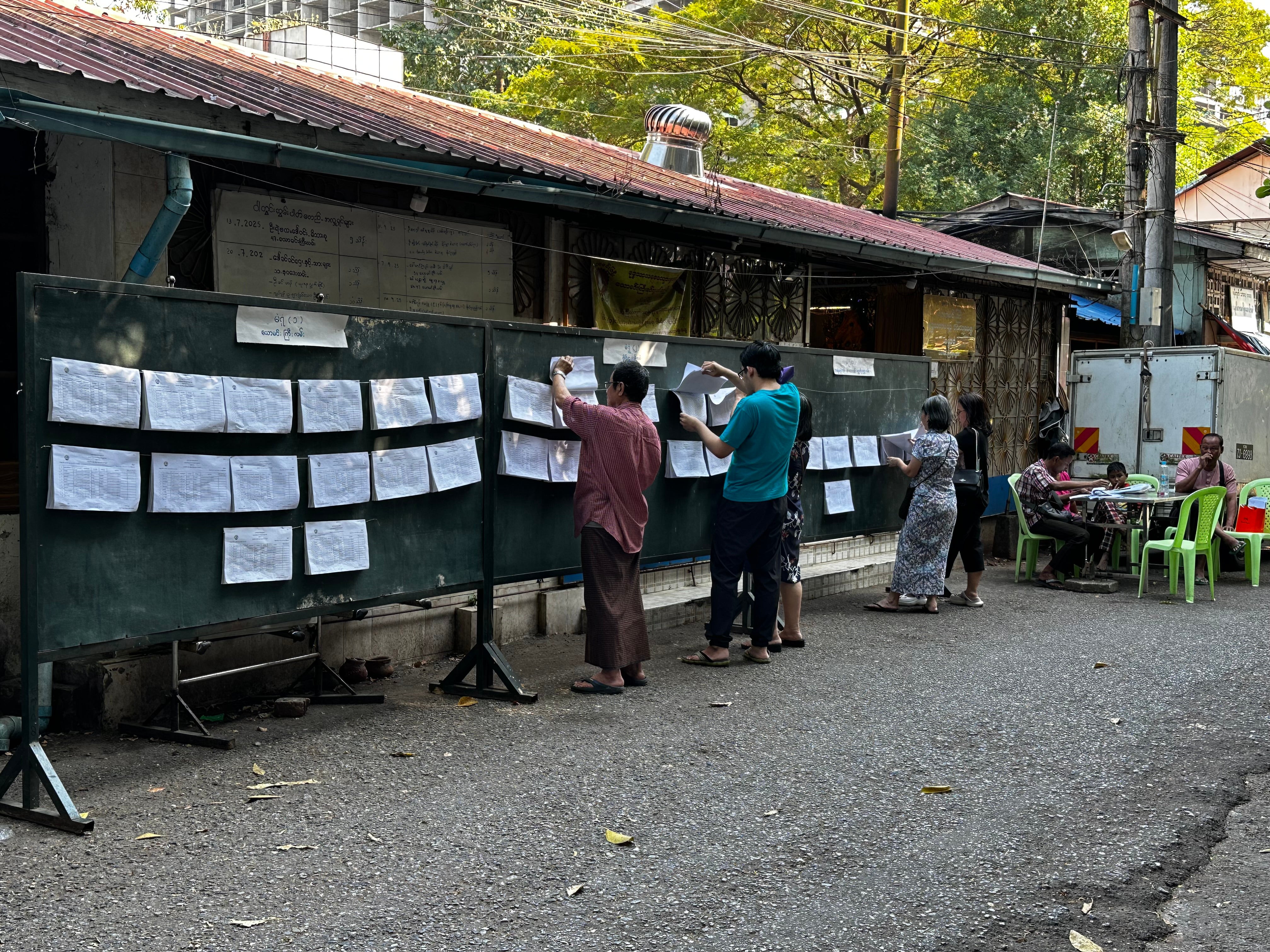

Members of Myanmar's Union Election Commission (UEC) prepare a polling station during the first phase of Myanmar's general election in Yangon, Dec. 28. AFP-Yonhap

YANGON, Myanmar — Overshadowed by civil war and doubts about the credibility of the polls, voters in Myanmar were casting their ballots in a general election starting on Sunday, the first since a military coup toppled the last civilian government in 2021.

The junta that has since ruled Myanmar says the vote is a chance for a fresh start politically and economically for the impoverished Southeast Asian nation.

But the election has been derided by critics — including the United Nations, some Western countries and human rights groups — as an exercise that is not free, fair or credible, with anti-junta political parties not competing.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, deposed by the military months after her National League for Democracy won the last general election by a landslide in 2020, remains in detention, and the political party she led to power has been dissolved.

Polls to prolong junta's 'power of slavery,' academic says

Mass protests followed the ouster of Suu Kyi's party, only to be violently suppressed by the military. Many protesters then took up arms against the junta in what became a nationwide rebellion.

In this election, the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, led by retired generals and fielding one-fifth of all candidates against severely diminished competition, is set to return to power, said Lalita Hanwong, a lecturer and Myanmar expert at Thailand's Kasetsart University.

"The junta's election is designed to prolong the military's power of slavery over people," she said. "And USDP and other allied parties with the military will join forces to form the next government."

Following the initial phase on Sunday, two rounds of voting will be held on January 11 and January 25, covering 265 of Myanmar's 330 townships, although the junta does not have complete control of all those areas as it fights in the war that has consumed the country since the coup.

Dates for counting votes and announcing election results have not been declared.

With fighting still raging in parts of the country, the elections are being held in an environment of violence and repression, U.N. human rights chief Volker Turk said last week.

"There are no conditions for the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, association or peaceful assembly that allow for the free and meaningful participation of the people," said Turk, the high commissioner for human rights.

Voters wait for a polling station to open in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, Dec. 28. AP-Yonhap

Election to 'turn new page for Myanmar,' state media says

The junta maintains that the elections provide a pathway out of the conflict, pointing to previous military-backed polls, including one in 2010 that brought in a quasi-civilian government that pushed through a series of political and economic reforms.

The polls "will turn a new page for Myanmar, shifting the narrative from a conflict-affected, crisis-laden country to a new chapter of hope for building peace and reconstructing the economy," an opinion piece in the state-run Global New Light of Myanmar said on Saturday.

On the streets of Myanmar's largest cities, there has been none of the energy and excitement of previous election campaigns, residents said, although they did not report any coercion by the military administration to push people to vote.

In the lacklustre canvassing, the USDP was the most visible. Founded in 2010, the year it won an election boycotted by the opposition, the party ran the country in concert with its military backers until 2015, when it was swept away by Suu Kyi's NLD.

The junta's attempt to establish a stable administration in the midst of an expansive conflict is fraught with risk, analysts say, and significant international recognition is unlikely for any military-controlled government — even if it has a civilian veneer.

Myanmar's weakened economy, relentless conflict and a seemingly preordained political route have left some voters dejected, including a 31-year-old man who lives in the commercial capital Yangon.

"No matter who I vote for, the USDP will win," he said, asking not to be named for fear of retribution from junta authorities. "So, I will just vote USDP."

Members of Myanmar's Union Election Commission (UEC) prepare a polling station during the first phase of Myanmar's general election in Yangon, Dec. 28. AFP-Yonhap

YANGON, Myanmar — Overshadowed by civil war and doubts about the credibility of the polls, voters in Myanmar were casting their ballots in a general election starting on Sunday, the first since a military coup toppled the last civilian government in 2021.

The junta that has since ruled Myanmar says the vote is a chance for a fresh start politically and economically for the impoverished Southeast Asian nation.

But the election has been derided by critics — including the United Nations, some Western countries and human rights groups — as an exercise that is not free, fair or credible, with anti-junta political parties not competing.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, deposed by the military months after her National League for Democracy won the last general election by a landslide in 2020, remains in detention, and the political party she led to power has been dissolved.

Polls to prolong junta's 'power of slavery,' academic says

Mass protests followed the ouster of Suu Kyi's party, only to be violently suppressed by the military. Many protesters then took up arms against the junta in what became a nationwide rebellion.

In this election, the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, led by retired generals and fielding one-fifth of all candidates against severely diminished competition, is set to return to power, said Lalita Hanwong, a lecturer and Myanmar expert at Thailand's Kasetsart University.

"The junta's election is designed to prolong the military's power of slavery over people," she said. "And USDP and other allied parties with the military will join forces to form the next government."

Following the initial phase on Sunday, two rounds of voting will be held on January 11 and January 25, covering 265 of Myanmar's 330 townships, although the junta does not have complete control of all those areas as it fights in the war that has consumed the country since the coup.

Dates for counting votes and announcing election results have not been declared.

With fighting still raging in parts of the country, the elections are being held in an environment of violence and repression, U.N. human rights chief Volker Turk said last week.

"There are no conditions for the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, association or peaceful assembly that allow for the free and meaningful participation of the people," said Turk, the high commissioner for human rights.

Voters wait for a polling station to open in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, Dec. 28. AP-Yonhap

Election to 'turn new page for Myanmar,' state media says

The junta maintains that the elections provide a pathway out of the conflict, pointing to previous military-backed polls, including one in 2010 that brought in a quasi-civilian government that pushed through a series of political and economic reforms.

The polls "will turn a new page for Myanmar, shifting the narrative from a conflict-affected, crisis-laden country to a new chapter of hope for building peace and reconstructing the economy," an opinion piece in the state-run Global New Light of Myanmar said on Saturday.

On the streets of Myanmar's largest cities, there has been none of the energy and excitement of previous election campaigns, residents said, although they did not report any coercion by the military administration to push people to vote.

In the lacklustre canvassing, the USDP was the most visible. Founded in 2010, the year it won an election boycotted by the opposition, the party ran the country in concert with its military backers until 2015, when it was swept away by Suu Kyi's NLD.

The junta's attempt to establish a stable administration in the midst of an expansive conflict is fraught with risk, analysts say, and significant international recognition is unlikely for any military-controlled government — even if it has a civilian veneer.

Myanmar's weakened economy, relentless conflict and a seemingly preordained political route have left some voters dejected, including a 31-year-old man who lives in the commercial capital Yangon.

"No matter who I vote for, the USDP will win," he said, asking not to be named for fear of retribution from junta authorities. "So, I will just vote USDP."

With only parties vetted by the military allowed to contest Myanmar’s first election in five years, Sara Perria speaks to people in Yangon and Mandalay who are heading out to vote because they are being forced – not out of any hope for a better future

THE INDEPENDENT

Saturday 27 December 2025

open image in galleryVolunteers with the junta-backed USDP party out campaigning in Thaketa township, Yangon on Friday morning (Sara Perria)

As Myanmar goes to the polls on Saturday in the first of three phases in a tightly controlled election, brightly coloured campaign posters loom over families with children still hacking a living from the rubble of buildings destroyed in Mandalay’s devastating earthquake nine months ago.

People here in Mandalay and in the commercial capital Yangon express a mix of anger and resignation over this so-called democratic exercise, in stark contrast to the enthusiasm seen in the votes of 2020 and 2015, when Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy defeated the military’s proxy party and its allies by a landslide.

Bulldozers throw up clouds of dust over streets now packed with traffic and people, as well as the billboards advertising the few parties vetted by the junta and allowed to stand in the polls, the first since the generals ousted Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government in a coup nearly five years ago.

The earthquake killed thousands of people and propelled Myanmar back onto the international stage, as many countries contributed to the regime’s relief efforts. But if the junta thought that spelled its reintegration into the global fold then it was mistaken; many of those same countries, as well as the resistance forces across Myanmar, have denounced these elections as far from free and fair in the midst of civil war.

“We are forced to go and vote this time. We don’t know what could happen to us if we don’t,” says Khin Nang* in Mandalay. Her brother is a political prisoner and she has to be careful. “We hope for an amnesty after the elections,” she says, as she fills a bag with avocados, oranges, biscuits, cooked meat and prawns to take to him. “Prison food is not good,” she adds.

open image in galleryAn election sign in front of a pile of rubble in Mandalay, Myanmar (Sara Perria)

“I’ll go and vote because I have to. The system is electronic for the first time and it’s not even possible to leave a blank,” says Zaw Zaw. “I don’t even know the names of the people running or their parties.”

In Yangon, close to Bokyoke Aung San market, named after Aung San Suu Kyi’s father and independence leader, people check their names on electoral lists posted in public.

Many say they will vote out of fear of punishment, others openly declare they will boycott the process. A few families are divided, with some mostly older members saying they will choose the military’s political proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

open image in galleryFile: In this photo taken on 14 March, 2016 Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi (R) is accompanied by Lower House speaker Win Myint (L) after a meeting of National League for Democracy (NLD) members of parliament in Naypyidaw (AFP via Getty Images)

Myanmar’s main regime-controlled cities in the heart of the country are relatively insulated from the conflict that has raged between the military and a combination of long-standing ethnic armed groups and the People’s Defence Forces, which formed after the 2021 coup. The military has been able to hold on in the centre largely thanks to its artillery and air power, often striking civilian targets like hospitals and schools in an attempt to weaken grassroots support for resistance groups.

A heavily weakened economy somehow still functions, but soaring food prices and extreme housing difficulties weigh on the urban centres swollen with people seeking refuge from the fighting and natural disasters. While most of the country struggles, wealthier Burmese can enjoy well-stocked markets, imported food, and a night scene of live music and restaurants, five-star hotels filled with Christmas decorations and few military uniforms in sight.

open image in galleryThe USDP junta-backed party out campaigning in Thaketa township, Yangon on Friday morning (Sara Perria)

Largely thanks to direct intervention by neighbouring China and drone technology and other military support supplied by Russia, the regime has regained substantial territory it lost following an October 2023 offensive launched in Shan State in the west and in eastern Rakhine by an alliance of ethnic groups. The rebel advance was initially endorsed by China, partly with the aim of cracking down on a vast complex of scam centres, some operated by Chinese criminal gangs close to its border and targeting Chinese citizens.

In a clear demonstration of how Beijing is now firmly backing the junta, China in August hosted Myanmar’s coup leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, during 80th anniversary celebrations of victory over Japan, alongside Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

“There has been a turning point in the country, since China’s more explicit siding with the regime,” says a diplomat in Yangon. “They are more in control. With these elections they just want to show their strength.”

Thousands of civilians have died in the conflict – the exact toll is not known – and over 20,000 political prisoners are still held in abysmal conditions, including Aung San Suu Kyi, of whom little information emerges.

open image in galleryA family works on the site of a building destroyed by the earthquake in Mandalay (Sara Perria)

Opposition to the elections is a new crime and more than 200 people have been arrested since July for related offences, such as critical social media posts and distributing anti-vote leaflets. Jail terms over 40 years have been imposed.

Aung San Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence for alleged corruption, charges which have been widely condemned as politically motivated. Her NLD and other anti-regime parties that refused to apply to register for the elections have been dissolved by the regime.

A lawyer in Bangkok familiar with Aung San Suu Kyi’s situation says she recently had dental trouble but does not receive proper medical assistance. There is some speculation that the elections will lead to an amnesty, but few believe her release is on the cards.

And while her reputation has been heavily dented outside Myanmar for defending the military’s onslaught against the Rohingya in 2017 – the subject of an Independent documentary released at this time a year ago – inside Myanmar she remains widely revered.

open image in galleryThe electoral list displayed alongside a poster in Myanmar (Sara Perria)

“We keep praying for her,” said Mya Hlaing, a teacher in Yangon, highlighting widespread affection for their former leader. “People go to Shwedagon Pagoda to pray for her on her birthday and take a red rose. Last time my sister said to be careful, it was too dangerous a political statement.”

There are, however, two factors making it less likely she could regain her pivotal role even if she survives detention: her age – she turned 80 in prison last June – and the emergence of a new generation of the Bamar majority leading the fight against the regime.

“Gen Z still respect her, but they wouldn’t listen to her,” says the lawyer.

“The country has to move on,” says Win Htet, a journalist and analyst in Yangon.

open image in galleryAn election poster on a street in Yangon, Myanmar (Sara Perria)

A garment factory owner in Yangon’s industrial zone hopes the elections will bring stability and more foreign investment. “We had to stop operations last month as all orders were cancelled because people are afraid of what’s happening.”

But few seem to believe that the junta’s installation of a nominally civilian government will put an end to a brutal civil war that involves not just ethnic armed groups concentrated in borderlands but now also the Bamar majority in the heartlands around Mandalay.

“What will change after these elections? Nothing,” replies Thiri.

* Names of people interviewed in Myanmar have been changed to protect their identities

Saturday 27 December 2025

open image in galleryVolunteers with the junta-backed USDP party out campaigning in Thaketa township, Yangon on Friday morning (Sara Perria)

As Myanmar goes to the polls on Saturday in the first of three phases in a tightly controlled election, brightly coloured campaign posters loom over families with children still hacking a living from the rubble of buildings destroyed in Mandalay’s devastating earthquake nine months ago.

People here in Mandalay and in the commercial capital Yangon express a mix of anger and resignation over this so-called democratic exercise, in stark contrast to the enthusiasm seen in the votes of 2020 and 2015, when Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy defeated the military’s proxy party and its allies by a landslide.

Bulldozers throw up clouds of dust over streets now packed with traffic and people, as well as the billboards advertising the few parties vetted by the junta and allowed to stand in the polls, the first since the generals ousted Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government in a coup nearly five years ago.

The earthquake killed thousands of people and propelled Myanmar back onto the international stage, as many countries contributed to the regime’s relief efforts. But if the junta thought that spelled its reintegration into the global fold then it was mistaken; many of those same countries, as well as the resistance forces across Myanmar, have denounced these elections as far from free and fair in the midst of civil war.

“We are forced to go and vote this time. We don’t know what could happen to us if we don’t,” says Khin Nang* in Mandalay. Her brother is a political prisoner and she has to be careful. “We hope for an amnesty after the elections,” she says, as she fills a bag with avocados, oranges, biscuits, cooked meat and prawns to take to him. “Prison food is not good,” she adds.

open image in galleryAn election sign in front of a pile of rubble in Mandalay, Myanmar (Sara Perria)

“I’ll go and vote because I have to. The system is electronic for the first time and it’s not even possible to leave a blank,” says Zaw Zaw. “I don’t even know the names of the people running or their parties.”

In Yangon, close to Bokyoke Aung San market, named after Aung San Suu Kyi’s father and independence leader, people check their names on electoral lists posted in public.

Many say they will vote out of fear of punishment, others openly declare they will boycott the process. A few families are divided, with some mostly older members saying they will choose the military’s political proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

open image in galleryFile: In this photo taken on 14 March, 2016 Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi (R) is accompanied by Lower House speaker Win Myint (L) after a meeting of National League for Democracy (NLD) members of parliament in Naypyidaw (AFP via Getty Images)

Myanmar’s main regime-controlled cities in the heart of the country are relatively insulated from the conflict that has raged between the military and a combination of long-standing ethnic armed groups and the People’s Defence Forces, which formed after the 2021 coup. The military has been able to hold on in the centre largely thanks to its artillery and air power, often striking civilian targets like hospitals and schools in an attempt to weaken grassroots support for resistance groups.

A heavily weakened economy somehow still functions, but soaring food prices and extreme housing difficulties weigh on the urban centres swollen with people seeking refuge from the fighting and natural disasters. While most of the country struggles, wealthier Burmese can enjoy well-stocked markets, imported food, and a night scene of live music and restaurants, five-star hotels filled with Christmas decorations and few military uniforms in sight.

open image in galleryThe USDP junta-backed party out campaigning in Thaketa township, Yangon on Friday morning (Sara Perria)

Largely thanks to direct intervention by neighbouring China and drone technology and other military support supplied by Russia, the regime has regained substantial territory it lost following an October 2023 offensive launched in Shan State in the west and in eastern Rakhine by an alliance of ethnic groups. The rebel advance was initially endorsed by China, partly with the aim of cracking down on a vast complex of scam centres, some operated by Chinese criminal gangs close to its border and targeting Chinese citizens.

In a clear demonstration of how Beijing is now firmly backing the junta, China in August hosted Myanmar’s coup leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, during 80th anniversary celebrations of victory over Japan, alongside Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

“There has been a turning point in the country, since China’s more explicit siding with the regime,” says a diplomat in Yangon. “They are more in control. With these elections they just want to show their strength.”

Thousands of civilians have died in the conflict – the exact toll is not known – and over 20,000 political prisoners are still held in abysmal conditions, including Aung San Suu Kyi, of whom little information emerges.

open image in galleryA family works on the site of a building destroyed by the earthquake in Mandalay (Sara Perria)

Opposition to the elections is a new crime and more than 200 people have been arrested since July for related offences, such as critical social media posts and distributing anti-vote leaflets. Jail terms over 40 years have been imposed.

Aung San Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence for alleged corruption, charges which have been widely condemned as politically motivated. Her NLD and other anti-regime parties that refused to apply to register for the elections have been dissolved by the regime.

A lawyer in Bangkok familiar with Aung San Suu Kyi’s situation says she recently had dental trouble but does not receive proper medical assistance. There is some speculation that the elections will lead to an amnesty, but few believe her release is on the cards.

And while her reputation has been heavily dented outside Myanmar for defending the military’s onslaught against the Rohingya in 2017 – the subject of an Independent documentary released at this time a year ago – inside Myanmar she remains widely revered.

open image in galleryThe electoral list displayed alongside a poster in Myanmar (Sara Perria)

“We keep praying for her,” said Mya Hlaing, a teacher in Yangon, highlighting widespread affection for their former leader. “People go to Shwedagon Pagoda to pray for her on her birthday and take a red rose. Last time my sister said to be careful, it was too dangerous a political statement.”

There are, however, two factors making it less likely she could regain her pivotal role even if she survives detention: her age – she turned 80 in prison last June – and the emergence of a new generation of the Bamar majority leading the fight against the regime.

“Gen Z still respect her, but they wouldn’t listen to her,” says the lawyer.

“The country has to move on,” says Win Htet, a journalist and analyst in Yangon.

open image in galleryAn election poster on a street in Yangon, Myanmar (Sara Perria)

A garment factory owner in Yangon’s industrial zone hopes the elections will bring stability and more foreign investment. “We had to stop operations last month as all orders were cancelled because people are afraid of what’s happening.”

But few seem to believe that the junta’s installation of a nominally civilian government will put an end to a brutal civil war that involves not just ethnic armed groups concentrated in borderlands but now also the Bamar majority in the heartlands around Mandalay.

“What will change after these elections? Nothing,” replies Thiri.

* Names of people interviewed in Myanmar have been changed to protect their identities

The UN has warned the military-controlled election is unfolding amid violence, intimidation and arrests. The country’s former leader has not been heard from in two years

Saturday 27 December

THE INDEPENDENT

Watch the trailer for Independent TV’s Aung San Suu Kyi documentary

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.Your support makes all the difference.Read more

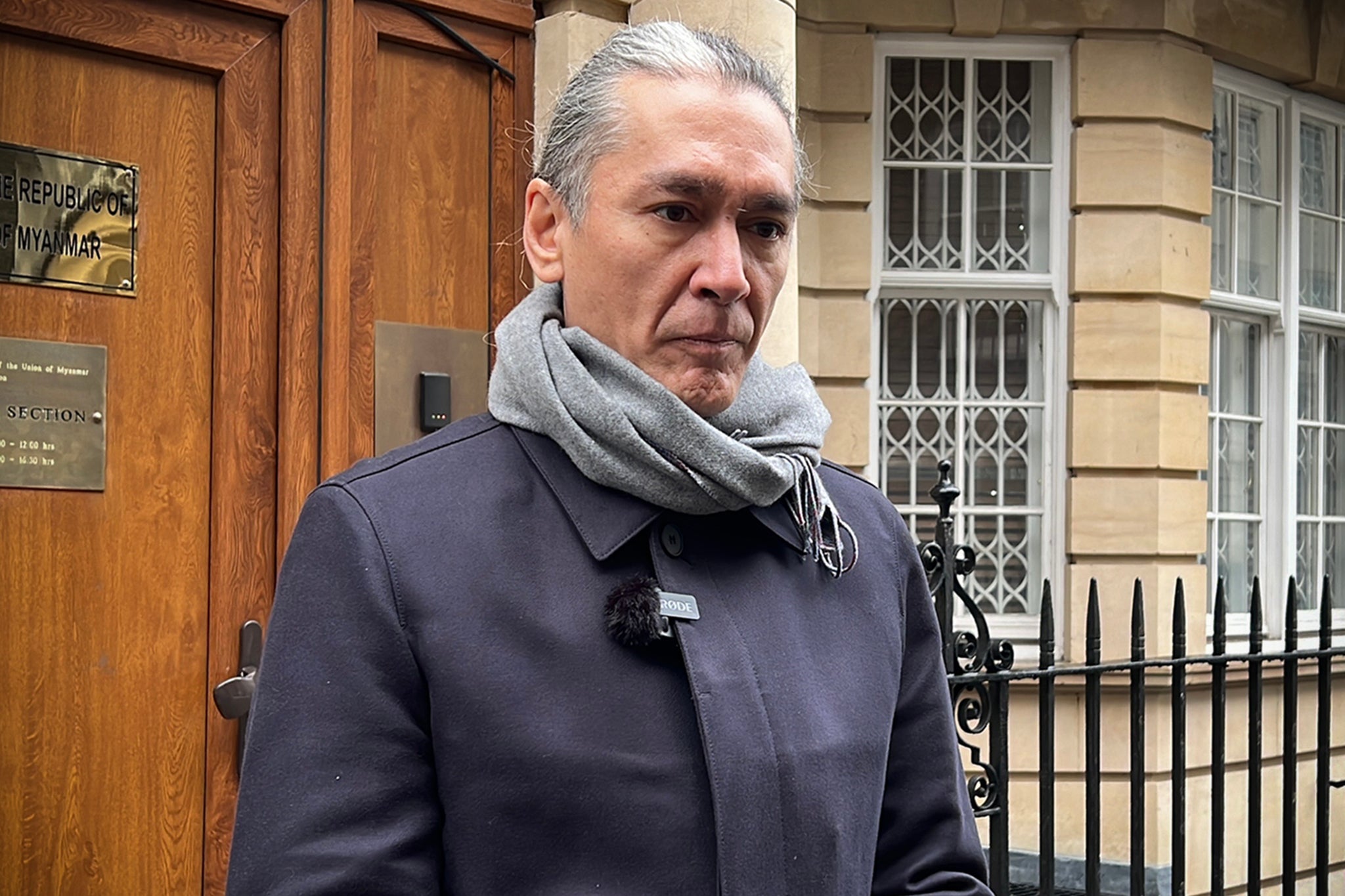

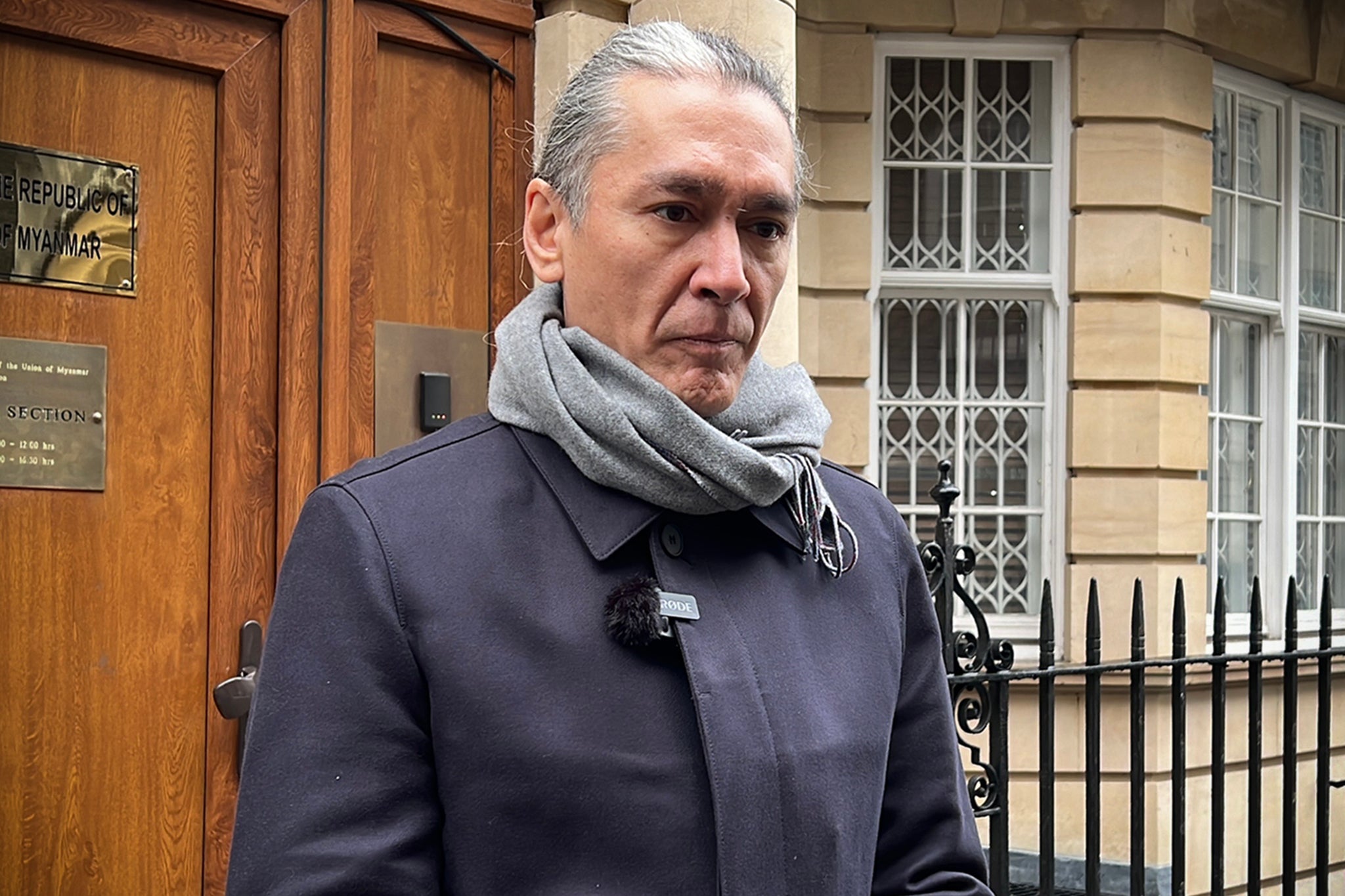

The UK’s foreign secretary, Yvette Cooper, is leading a new push to free Myanmar’s former leader Aung San Suu Kyi as sham elections in the country are set to begin.

The Foreign Office (FCDO) has issued a demand for Ms Suu Kyi to be released as the military junta in the country formerly known as Burma attempts to justify its rule with elections, which have excluded most of the opposition.

It comes as the UN has warned the military-controlled ballot is unfolding amid “intensified violence, intimidation and arbitrary arrests, leaving no space for free or meaningful participation”.

No political parties hostile to the junta have been permitted to run, with Ms Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) banned despite landslide victories in 2015 and 2020.

Ms Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence in Naypyidaw, the junta’s remote capital, on charges including alleged corruption, election fraud and several other charges, which have been widely condemned as politically motivated. A lawyer in Bangkok says she recently had dental trouble but did not receive proper medical assistance.

Her family have not heard from her directly in two years and fear that she may already be dead. The 80-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner has not been seen in public since the coup that overthrew the government in 2021.

open image in galleryAung San Suu Kyi was jailed after a series of show trials (Getty)

The Independent has been told that Ms Cooper is deeply concerned about the situation in the country and Ms Suu Kyi’s ongoing imprisonment.

An FCDO spokesperson told The Independent: “The UK government continues to condemn the detention of Aung San Suu Kyi. The military regime must release her and all those who are arbitrarily detained.

“The UK continues to shine a spotlight on Myanmar, including through our role at the UN Security Council.”

Sean Turnell, Ms Suu Kyi’s former economic policy adviser, spent 650 days in custody after the coup and branded the election “an utter sham.”

“It’s not even close to being a fair election,” he told The Independent. “I wish we were using a different word than ’election’ – a label that conveys nothing about this act of public intimidation that seeks to put lipstick on a particularly grotesque pig.

“The military are planning to stay absolutely in control. It’s very important for the international community right at the get-go to call the election out for what it is. Because this is really nothing but theatre.”

Ms Suu Kyi was sentenced to 33 years in jail after a series of show trials, later reduced to 27 years, and is being held in solitary confinement. A deeply controversial figure after refusing to speak out against her country’s extreme violence against its Rohingya Muslim minority, she is still seen by some as “Myanmar’s one great hope”.

open image in galleryMyanmar’s military junta will oversee the election (AFP/Getty)

The junta has insisted, without providing evidence, that the former leader “is in good health”, but her family fear the worst.

“She has ongoing health issues,” her son Kim Aris said in a recent interview. “Nobody has seen her in over two years.

“She hasn’t been allowed contact with the legal team, let alone the family. For all I know, she could be dead already. I don’t think she would consider these elections to be meaningful in any way.”

The first phase of the vote, scheduled for 28 December, comes amid a climate of armed conflict, mass displacement and economic collapse, the UN said.

Since 18 August, when the junta announced the election dates, at least 862 airstrikes have been conducted in 121 townships. Most recently, a hospital in Rakhine state was bombed, killing more than 30 people, while 18 more were killed when bombs fell on a teashop in the central Sagaing region while they were watching a football match.

open image in galleryDebris in an area allegedly hit by an airstrike in Mayakan village, Myanmar, in early December (AP)

The official election map shows large areas in the east, west and north where no polls will be held, while the entire map is dotted with large expanses where, the junta claims, “elections will take place at a later date”.

“These elections are clearly taking place in an environment of violence and repression,” the UN’s high commissioner for human rights, Volker Türk, warned this week. “There are no conditions for the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, association or peaceful assembly.”

Thousands of opponents were jailed after the coup, all protests have been criminalised, and dissenters face harsh punishment.

Three young artists in Yangon who put up anti-election posters were sentenced to 42 and 49 years. Elsewhere, a man who tore down a candidate list was jailed for 17 years.

Ms Suu Kyi’s son Kim Aris has called on the military junta in Myanmar to release his mother (The Independent)

A young man called Ko Nay Thway, in the city of Taunggyi, wrote on Facebook: “If [the junta] want the votes from the people, [they should] think of serving the people”. In response, he was sentenced to seven years under the new Election Protection Law.

Hanthar Nyein, a Myanmar journalist released after four years in jail in Yangon, said: “The military has just three ways of getting and remaining in power: seizing power in a coup, establishing an appearance of legitimacy through a fake party, then ruling permanently from behind the scenes using a puppet parliament.

“The 2008 constitution states that the army must play the leading role in national politics. The army claims that only its ‘guardianship’ prevents the nation, with its numerous ethnic minorities, from disintegrating.”

Critics argue it is military rule itself which has shattered the nation.

Sir John Jenkins, a former UK ambassador to Myanmar, told The Independent: “The generals may think they can solidify their tyranny on the back of a rigged win and perhaps even pretend to be magnanimous in the phoney aftermath.

“I wish it could be an opportunity for international actors to refocus on what matters: justice for all the people of Burma. I’m not holding my breath.”

Watch the trailer for Independent TV’s Aung San Suu Kyi documentary

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.Your support makes all the difference.Read more

The UK’s foreign secretary, Yvette Cooper, is leading a new push to free Myanmar’s former leader Aung San Suu Kyi as sham elections in the country are set to begin.

The Foreign Office (FCDO) has issued a demand for Ms Suu Kyi to be released as the military junta in the country formerly known as Burma attempts to justify its rule with elections, which have excluded most of the opposition.

It comes as the UN has warned the military-controlled ballot is unfolding amid “intensified violence, intimidation and arbitrary arrests, leaving no space for free or meaningful participation”.

No political parties hostile to the junta have been permitted to run, with Ms Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) banned despite landslide victories in 2015 and 2020.

Ms Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence in Naypyidaw, the junta’s remote capital, on charges including alleged corruption, election fraud and several other charges, which have been widely condemned as politically motivated. A lawyer in Bangkok says she recently had dental trouble but did not receive proper medical assistance.

Her family have not heard from her directly in two years and fear that she may already be dead. The 80-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner has not been seen in public since the coup that overthrew the government in 2021.

open image in galleryAung San Suu Kyi was jailed after a series of show trials (Getty)

The Independent has been told that Ms Cooper is deeply concerned about the situation in the country and Ms Suu Kyi’s ongoing imprisonment.

An FCDO spokesperson told The Independent: “The UK government continues to condemn the detention of Aung San Suu Kyi. The military regime must release her and all those who are arbitrarily detained.

“The UK continues to shine a spotlight on Myanmar, including through our role at the UN Security Council.”

Sean Turnell, Ms Suu Kyi’s former economic policy adviser, spent 650 days in custody after the coup and branded the election “an utter sham.”

“It’s not even close to being a fair election,” he told The Independent. “I wish we were using a different word than ’election’ – a label that conveys nothing about this act of public intimidation that seeks to put lipstick on a particularly grotesque pig.

“The military are planning to stay absolutely in control. It’s very important for the international community right at the get-go to call the election out for what it is. Because this is really nothing but theatre.”

Ms Suu Kyi was sentenced to 33 years in jail after a series of show trials, later reduced to 27 years, and is being held in solitary confinement. A deeply controversial figure after refusing to speak out against her country’s extreme violence against its Rohingya Muslim minority, she is still seen by some as “Myanmar’s one great hope”.

open image in galleryMyanmar’s military junta will oversee the election (AFP/Getty)

The junta has insisted, without providing evidence, that the former leader “is in good health”, but her family fear the worst.

“She has ongoing health issues,” her son Kim Aris said in a recent interview. “Nobody has seen her in over two years.

“She hasn’t been allowed contact with the legal team, let alone the family. For all I know, she could be dead already. I don’t think she would consider these elections to be meaningful in any way.”

The first phase of the vote, scheduled for 28 December, comes amid a climate of armed conflict, mass displacement and economic collapse, the UN said.

Since 18 August, when the junta announced the election dates, at least 862 airstrikes have been conducted in 121 townships. Most recently, a hospital in Rakhine state was bombed, killing more than 30 people, while 18 more were killed when bombs fell on a teashop in the central Sagaing region while they were watching a football match.

open image in galleryDebris in an area allegedly hit by an airstrike in Mayakan village, Myanmar, in early December (AP)

The official election map shows large areas in the east, west and north where no polls will be held, while the entire map is dotted with large expanses where, the junta claims, “elections will take place at a later date”.

“These elections are clearly taking place in an environment of violence and repression,” the UN’s high commissioner for human rights, Volker Türk, warned this week. “There are no conditions for the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, association or peaceful assembly.”

Thousands of opponents were jailed after the coup, all protests have been criminalised, and dissenters face harsh punishment.

Three young artists in Yangon who put up anti-election posters were sentenced to 42 and 49 years. Elsewhere, a man who tore down a candidate list was jailed for 17 years.

Ms Suu Kyi’s son Kim Aris has called on the military junta in Myanmar to release his mother (The Independent)

A young man called Ko Nay Thway, in the city of Taunggyi, wrote on Facebook: “If [the junta] want the votes from the people, [they should] think of serving the people”. In response, he was sentenced to seven years under the new Election Protection Law.

Hanthar Nyein, a Myanmar journalist released after four years in jail in Yangon, said: “The military has just three ways of getting and remaining in power: seizing power in a coup, establishing an appearance of legitimacy through a fake party, then ruling permanently from behind the scenes using a puppet parliament.

“The 2008 constitution states that the army must play the leading role in national politics. The army claims that only its ‘guardianship’ prevents the nation, with its numerous ethnic minorities, from disintegrating.”

Critics argue it is military rule itself which has shattered the nation.

Sir John Jenkins, a former UK ambassador to Myanmar, told The Independent: “The generals may think they can solidify their tyranny on the back of a rigged win and perhaps even pretend to be magnanimous in the phoney aftermath.

“I wish it could be an opportunity for international actors to refocus on what matters: justice for all the people of Burma. I’m not holding my breath.”

No comments:

Post a Comment