The race to mine mining waste

Could metal-eating bacteria that break down mining waste be key to sustainable battery minerals?

For generations, the topography of Sudbury, Ontario, has been brutally defined by towering slag heaps and vast orange-hued tailings ponds – the physical legacy of almost 140 years of nickel mining and smelting by resource giants like Inco and Falconbridge. By 1910, in fact, Sudbury’s mines were supplying 80% of the world’s nickel. But by the late 20th century, the industrial fallout – corrosive air pollution, acid rain and a legacy of seemingly intractable contamination – revealed the extraordinary environmental cost of those resource riches.

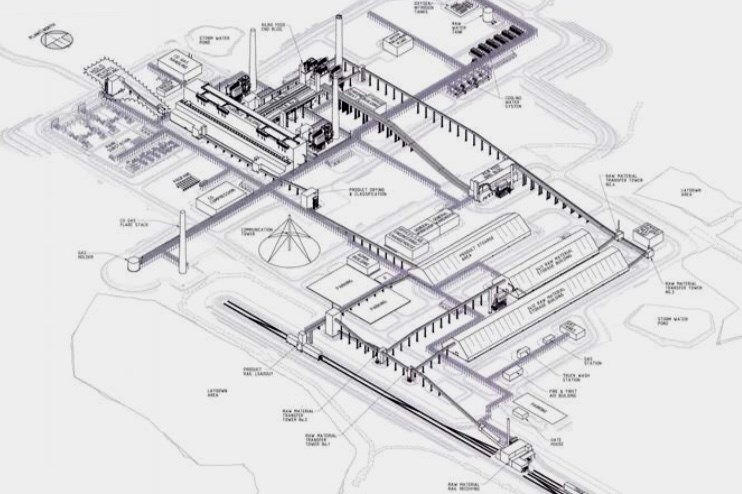

Fast forward to April 2022, when BacTech, a publicly traded Toronto remediation firm, launched plans to use naturally occurring bacteria and a “bioleaching” process to break down some of that mining waste and recover what it claims are billions of dollars in nickel, cobalt, green iron and sulphur that have long been buried in those tailings. Nickel and cobalt are now highly sought-after minerals in the accelerating race to build electric vehicle batteries, and this venture seems to offer a double climate bonus: remediation of a highly degraded landscape, as well as raw materials for transportation technology that weans society of its addiction to fossil fuels.

“The timing is right to mature these technologies off the bench,” says Laurentian University microbiologist Nadia Mykytczuk, interim president and CEO of MIRARCO (Laurentian’s Mining Innovation, Rehabilitation and Applied Research Corporation) and an advisor to BacTech. “The rapid electrification and move to battery electric vehicles is going to drive a lot of innovations, and bioleaching is one of those that will move forward quite quickly now.” A feasibility study has been completed, and a pilot facility, the Centre for Mine Waste Biotechnology, is being built on the Laurentian campus.

Mykytczuk points out that the notion of using microbes to essentially poop out recoverable minerals from tailings waste isn’t new, and has been applied for decades in settings like Chile’s copper mines. Over time, however, the processes have become more sophisticated; the demand for better forms of remediation, more intense. Acid drainage, a corrosive by-product that’s released from tailings ponds, continues to contaminate downstream watersheds. Tailings dam disasters in the past decade or so in countries such as Hungary, South Africa and Brazil have not only shone a harsh light on the grave human and ecological risks associated with accumulated mining waste, but also sparked activist investor groups, like the Church of England, to push for safer practices.

At the same time, the global growth of renewable energy and the push to electrify has revealed the extent to which fossil fuel extraction will be replaced in the coming decades by the dramatic growth in the mining of ores like nickel, copper or rare earth elements used in wind turbines and other clean technologies. Global demand for copper is projected to double by 2035, even as existing copper mines become less and less productive. Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency estimated that the global mining sector needs to build 60 nickel mines, 50 lithium mines and 17 cobalt mines by 2030 to meet global emissions goals.

But if all that new mining activity generates even more emissions, contaminates watersheds and produces mountains of toxic waste, we’ll have merely replaced one form of resource-driven environmental destruction with another. Case in point: the mining of lithium, a critical ingredient in EV batteries, consumes huge quantities of water, pollutes groundwater and poses a danger to flamingo habitats.

Conventional mining is not only energy intensive and ecologically scarring; it is also extraordinarily inefficient. By weight and volume, valuable ores like nickel, gold or cobalt account for a tiny fraction – sometimes even less than 1% – of all the material removed from a mine. (A sustainable-mining scholar in Chile has trenchantly described these epic inefficiencies as akin to using five kilograms of beef from a 500-kilo cow and discarding the rest.) What’s more, the structure and financing of the industry is such that individual mining companies traditionally produce only one or two substances; everything else is seen as waste.

From an emissions perspective, one of the core arguments in favour of biomining and remining (another approach to recovering marketable minerals from tailings) is that huge amounts of energy have already been consumed to extract, crush, separate and process all the material that comes out of a mine. “The total energy required for bioleaching is significantly lower by several orders of magnitude than if you were to build a high-energy smelter,” says Mykytczuk.

To date, biomining remains a tiny fragment of the industry, but the potential has garnered attention from researchers, cleantech start-ups and established mining giants. For example, Teck Resources and Rio Tinto, both global firms, have teamed up with researchers at the University of British Columbia and other organizations to launch a project called M-MAP, or the Mining Microbiome Analytics Platform. The organization is building a genome library of microbes found in tailings ponds around the world, which will allow labs to sequence genetic material to engineer bacteria that is essentially tailor-made to digest minerals in particular tailings ponds.

As a Teck spokesperson explains, “M-MAP is the first integrated online platform which aims to extract the DNA from more than 15,000 mining site samples over the next two years to identify microbes that can be used to replace chemical and other legacy extraction methods for minerals and metals, and to perform safer, more effective remediation of legacy and operational mine sites.”

Bryne Gramlich, vice-president of business development at Allonnia, a Boston bio-engineering firm that is part of the M-MAP consortia, adds that while the project is in its infancy, the mining sector is “aggressively looking at how to accelerate the use of biology” in its reclamation efforts.

The rapid electrification and move to battery electric vehicles is going to drive a lot of innovations, and bioleaching is one of those that will move forward quite quickly now.

-Nadia Mykytczuk, interim president and CEO of MIRARCO

The critical question, of course, is whether the introduction of specially engineered microbes in tailings ponds, such as those enabled by M-MAP’s genome library, could further exacerbate environmental damage downstream of such facilities. “In order to get any type of technology like this approved and indeed used,” says Anita Parbhakar-Fox, an associate professor at Australia’s University of Queensland who runs a mine-waste-transformation research group, “a rigorous environmental impact assessment, including demonstration testing, risk evaluation and impact modelling, would be undertaken to ensure a decision on whether to use the technology was made based on a full evaluation of the socio-environmental risks.”

But Radhakrishnan Mahadevan, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Toronto and a Canada Research Chair specializing in bio-engineering applications, says there are existing techniques for ensuring that such microbes don’t have what he describes as “exogenous impacts,” such as increasing the risk of antibiotic resistance. “You can engineer the environment in such a way that the microbes do what you want them to do.”

The potential for using new technologies to upcycle mining waste has attracted other remining start-ups. Phoenix Tailings, a four-year-old Boston firm with venture capital backing, has developed a set of chemical processes to extract value from tailings, including rare earth elements, cobalt and nickel. According to co-founder Anthony Balladon, the firm’s business strategy with mine waste sites is to recover two types of materials: large volumes of inert bulk substances that can be used like aggregates in concrete production, and smaller volumes of valuable ores. To make the math work, he says, “we need both components.”

He points out that some waste sites are quite old and date to a time when there was little market for the metals that are now driving the electrification economy. “You often find that you have a tailings pile or tailings pond somewhere in Canada, Australia or the U.S. that has a higher grade of cobalt or copper or rare earths than what is currently considered the kind of grade for operating a new mine,” he says. “You have to find the right sites.”

Phoenix, Balladon notes, has tapped into an eager source of capital looking for sustainable solutions to mining waste and a way of averting tailings dam disasters. But global investor appetite for EV-related metals is voracious and also a major driver of these technologies. “It’s a very exciting time,” he says, noting that governments in Canada, the U.S. and Australia are all looking to invest in these approaches.

You often find that you have a tailings pile or tailings pond somewhere in Canada, Australia or the U.S. that has a higher grade of cobalt or copper or rare earths than what is currently considered the kind of grade for operating a new mine.

-Anthony Balladon, co-founder, Phoenix Tailings

Parbhakar-Fox agrees. “In Australia in the past three to five years, we have seen a great deal of state and federal government investment into the development of mineral processing methodologies, particularly to recover critical metals in order to grow this sector in Australia,” she says. “The University of Queensland is involved in a project to bioleach and recover [rare earth elements] from Mary Kathleen mine tailings, potentially containing AU$4 billion worth, as well as cobalt from the Old Tailings Dam and Savage River mine tailings [in western Tasmania].” BacTech sees even larger economic windfall from recovering copper and cobalt from the tailings in Sudbury – it estimates that there’s $27 billion in nickel alone sitting in those ponds.

Researchers say these processes also promise a climate benefit beyond energy savings. “The bioleaching process itself is carbon capturing,” says Mykytczuk. “We are capturing atmospheric CO2, and the bacteria fix that to their biomass [so] you can actually have an offset from your carbon cost in the bioleaching process. It’s a benefit on the carbon side of things.”

There is, of course, plenty of reason to be skeptical, not just about the science, which is nascent and not yet deployed at commercial scale, but also about the promise of alchemizing all that slag into valuable ore and billions of dollars in profits.

Yet advocates point out that emerging research and the climate imperative should be encouraging us to think differently about the largely unseen by-products of an extractive industry that hasn’t changed its ways in generations.

“Mining tailings and other mine wastes are multifaceted when it comes to the potential positive outcomes,” says Parbhakar-Fox. “Provided the mine waste has been well characterized and the right technologies are used to extract and recover the most value, there are positive outcomes for companies, the environment, the future, and for our governments to grow circular economy businesses. These are exciting times if we dare to dream and think outside the box.”