By Jonathan Amos

BBC Science Correspondent

APRIL 30, 2020

What happens to microplastics in the ocean?

VIDEOS AT THE END

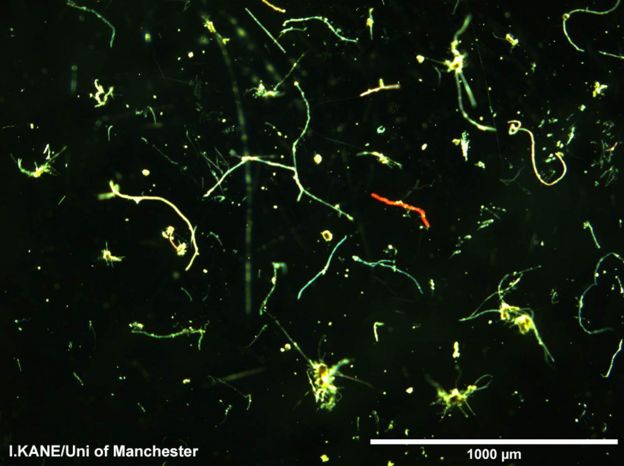

Scientists have identified the highest levels of microplastics ever recorded on the seafloor.

The contamination was found in sediments pulled from the bottom of the Mediterranean, near Italy.

The analysis, led by the University of Manchester, found up to 1.9 million plastic pieces per square metre.

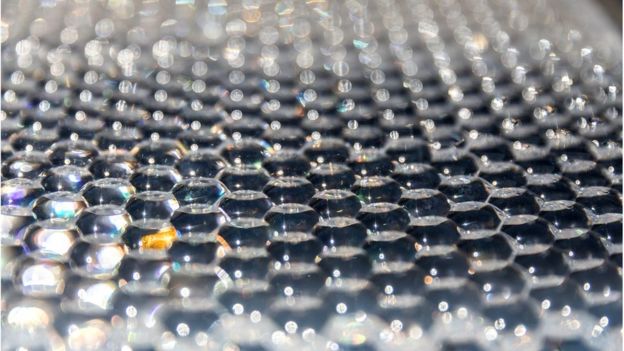

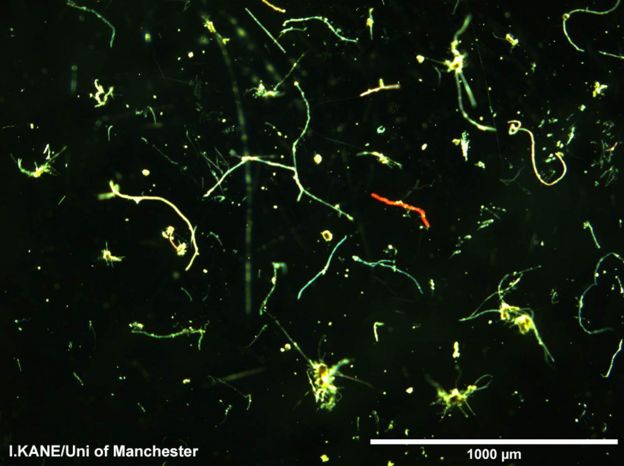

These items likely included fibres from clothing and other synthetic textiles, and tiny fragments from larger objects that had broken down over time.

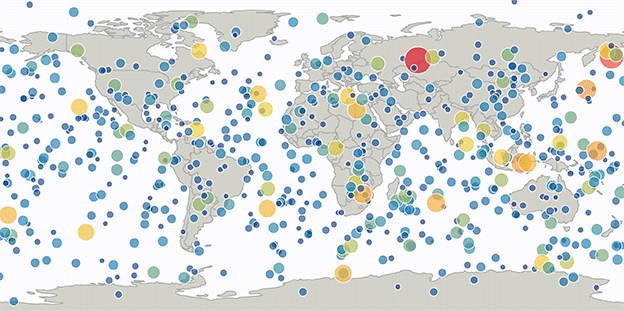

The researchers' investigations lead them to believe that microplastics (smaller than 1mm) are being concentrated in specific locations on the ocean floor by powerful bottom currents.

"These currents build what are called drift deposits; think of underwater sand dunes," explained Dr Ian Kane, who fronted the international team.

"They can be tens of kilometres long and hundreds of metres high. They are among the largest sediment accumulations on Earth. They're made predominantly of very fine silt, so it's intuitive to expect microplastics will be found within them," he told BBC News.

APRIL 30, 2020

What happens to microplastics in the ocean?

VIDEOS AT THE END

Scientists have identified the highest levels of microplastics ever recorded on the seafloor.

The contamination was found in sediments pulled from the bottom of the Mediterranean, near Italy.

The analysis, led by the University of Manchester, found up to 1.9 million plastic pieces per square metre.

These items likely included fibres from clothing and other synthetic textiles, and tiny fragments from larger objects that had broken down over time.

The researchers' investigations lead them to believe that microplastics (smaller than 1mm) are being concentrated in specific locations on the ocean floor by powerful bottom currents.

"These currents build what are called drift deposits; think of underwater sand dunes," explained Dr Ian Kane, who fronted the international team.

"They can be tens of kilometres long and hundreds of metres high. They are among the largest sediment accumulations on Earth. They're made predominantly of very fine silt, so it's intuitive to expect microplastics will be found within them," he told BBC News.

SOURCE: I.KANE/UNI OF MANCHESTER

It's been calculated that something in the order of four to 12 million tonnes of plastic waste enter the oceans every year, mostly through rivers.

Media headlines have focussed on the great aggregations of debris that float in gyres or wash up with the tides on coastlines.

But this visible trash is thought to represent just 1% of the marine plastic budget. The exact whereabouts of the other 99% is unknown.

Some of it has almost certainly been consumed by sea creatures, but perhaps the much larger proportion has fragmented and simply sunk.

It's been calculated that something in the order of four to 12 million tonnes of plastic waste enter the oceans every year, mostly through rivers.

Media headlines have focussed on the great aggregations of debris that float in gyres or wash up with the tides on coastlines.

But this visible trash is thought to represent just 1% of the marine plastic budget. The exact whereabouts of the other 99% is unknown.

Some of it has almost certainly been consumed by sea creatures, but perhaps the much larger proportion has fragmented and simply sunk.

A lot of the fibres will come from clothing and other textiles

Dr Kane's team has already shown that deep-sea trenches and ocean canyons can have high concentrations of microplastics in their sediments.

Indeed, water tank simulations run by the group have demonstrated just how efficiently flows of mud, sand and silt of the type occurring in canyons will entrain and move fibres to even greater depths.

"A single one of these underwater avalanches ('turbidity currents') can transport tremendous volumes of sediment for 100s of kilometres across the ocean floor," said Dr Florian Pohl from Durham University.

"We're just starting to understand from recent laboratory experiments how these flows transport and bury microplastics."

Tank experiments show how underwater avalanches could transport plastic particles into the deep

There is nothing atypical about the study area in the Tyrrhenian basin between Italy, Corsica and Sardinia.

Many other parts of the globe have strong deep-water currents that are driven by temperature and salinity contrasts. The issue of concern will be that these currents also supply oxygen and nutrients to deep-sea creatures. And so by following the same route, the microplastics could be settling into biodiversity hotspots, increasing the chance of ingestion by marine life.

GETTY IMAGE

Beach plastic may be a very small fraction of the waste out there

Prof Elda Miramontes from the University of Bremen, Germany, is a co-author on the Science journal paper describing the Mediterranean discovery.

She says the same effort shown in the battle against coronavirus must now take on the scourge of ocean plastic pollution.

"We're all making an effort to improve our safety and we are all staying at home and changing our lives - changing our work life, or even stopping work," she told BBC News. "We're doing all this so that people are not affected by this sickness. We have to think in the same way when we protect our oceans."

Roland Geyer is professor of industrial ecology at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California at Santa Barbara.

He has been at the forefront of investigating and describing the waste streams through which plastic gets into the oceans.

He commented: "We still have a very poor understanding of how much total plastic has accumulated in the oceans. There seems to be one emerging scientific consensus, which is that most of that plastic is not floating on the ocean surface.

"Many scientists now think that most of the plastic is likely to be on the ocean floor, but the water column and the beaches are also likely to contain major quantities.

"We really should all be completely focused on stopping plastic from entering the oceans in the first place."

Prof Elda Miramontes from the University of Bremen, Germany, is a co-author on the Science journal paper describing the Mediterranean discovery.

She says the same effort shown in the battle against coronavirus must now take on the scourge of ocean plastic pollution.

"We're all making an effort to improve our safety and we are all staying at home and changing our lives - changing our work life, or even stopping work," she told BBC News. "We're doing all this so that people are not affected by this sickness. We have to think in the same way when we protect our oceans."

Roland Geyer is professor of industrial ecology at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California at Santa Barbara.

He has been at the forefront of investigating and describing the waste streams through which plastic gets into the oceans.

He commented: "We still have a very poor understanding of how much total plastic has accumulated in the oceans. There seems to be one emerging scientific consensus, which is that most of that plastic is not floating on the ocean surface.

"Many scientists now think that most of the plastic is likely to be on the ocean floor, but the water column and the beaches are also likely to contain major quantities.

"We really should all be completely focused on stopping plastic from entering the oceans in the first place."

I.KANE/UNI OF MANCHESTER

The sediments were brought up as part of work on a seafloor pipeline

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter:.