And the Four Day Week.

And the Four Day Week.

While surfing I came across this interesting site on an alternative to downsizing workers, downsizing the work day. See links below.

Not a new idea but one that resurfaces when whenever capitalism adopts new technology to reduce labour costs. As Dr. Marx pointed out the class struggle is all about reducing the work day.

This began with the 10 hour movement during the late 19th Century, and quickly grew into the 8 hour movement. You know the saying, "The Weekend,brought to you by the Labour Movement".

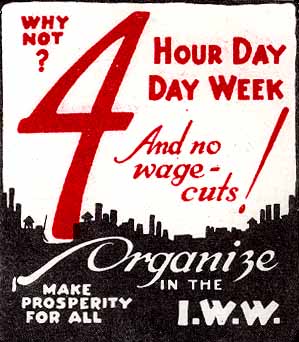

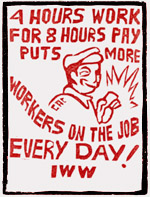

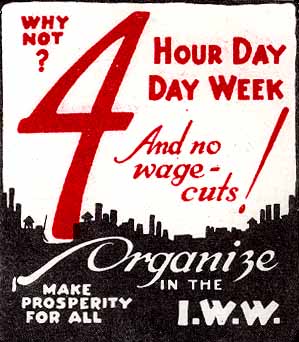

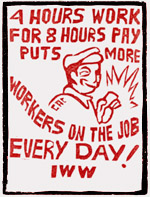

The Syndicalist movement in North America called for a 4 hour work day. This was advanced by the IWW in the 1920's!!!. In the 1920's folks. 75 years ago. And today folks are working two jobs and most are working 44-50 hours a week to make ends meet.

Work time has increased, while wages have decreased in real money, and work has become contracted out and precarious.

In the 1930's the Progressive Labour Party and others in the labour movement called for a 32 hour work week, in otherwords a four day week. Even this revisionist demand was met with capitalist distain. Today France has a 35 hour work week which was not without controversy.

Today as more workers are laid off, the Canadian Autoworkers Union has fought and bargianed against forced overtime in favour of increased jobs.

Today as more workers are laid off, the Canadian Autoworkers Union has fought and bargianed against forced overtime in favour of increased jobs.

We still hear from folks who offer the 32 hour week as their minimum demand, and thats the problem, its a minimum, and even then capitalism has not embraced it with anymore enthusiaism than the 4 hour day and the 4 day week.

Reducing Working Time

The European Union (EU) Directive on working time (Directive 93/104/EC) required member states to introduce national legislation that would reduce working time to a weekly average of forty eight (48) hours in a year. The 'Organisation of Working Time Act, 1997' has transposed the EU Directive into law in Ireland. This new law has impacted on the dependence that enterprises can have on excessive overtime working. It also reduces the maximum number of hours that employees are allowed to work. In this context both employers and unions are exploring the possible potential of combining changes in work organisation with changes in the pattern of working hours. While employers and unions can have different aims for any reorganisation of work and working time, a recognition of the interdependence of these aims should provide a basis for joint examination of what can be done. In short, the chances for employees to improve guaranteed earnings while working fewer hours are likely to be better if working time can be more effectively matched with the actual needs of the enterprise.

Another group influenced by the IWW and North American Syndicalism was Technocracy Inc. which also adopted the idea that the MAXIMUM labour required to maintain an advanced industrial society is wait for it, yep, a 4 hour day, 4 days a week.

The Price System be abolished, and be replaced with an Energy Credit”-system. The Energy Credit is an electronic distribution unit of which the value is determined by the resources which the system could distribute to it’s clients, and the costs is equivalent with the production costs – because profit is eliminated. The investments could instead be developed through the total independence and autarchy of the system, and in time, the system will be impossible to destroy. The Energy Credit could never be bartered, loaned, speculated, inflated, stolen or be misused for corrupt purposes, because it’s value and areas of legitimacy is fixated. All inhabitants within the borders of the Technate are given a standard income of energy credits, free residence of living, free means of communication, free clothes, free food, free healthcare, free education, and free recreation. The work time is 4 hours a day, 4 days a week, but it will in each case be a hard task to give everyone a job, but that is not a problem, because everyone will prosper and survive, work or no work. “Machines work, humans play”, as one of the mottos sound.

For a larger picture of this chart click here.

For a larger picture of this chart click here.

The Mystery of Money G. D. KOE, CHQ • 1938

The machine is here to stay. It is emancipating the wage slaves who in ever increasing numbers are becoming like the lilies of the field: they toil not, neither do they spin. The machine does not strike nor talk back and it requires no relief when unemployed. If you wish to continue your Price System you will have to breed a new race of men, men that can lie fallow for a season, or can be stored away in warehouses till they are required.

Human labor means wages. Wages means purchasing power. Purchasing power means profits and profits means savings. Savings mean more and more means of production. And so round and round the endless chain of the Price System. Men work so that they may consume, and consume so that they may have strength to work some more so that they may continue to consume, while close behind comes the grim spectre of scarcity. To protect themselves they saved themselves into the jaws of unemployment. Savings built machines.

When electric power came, human labor lost. Electric power works twenty-four hours and it draws no wages, but the owners pile up savings. More savings, more machines, more production, more machines, less wages, less purchasing power, less employment, larger relief rolls, over production. Still more dividends are being paid and still more savings are being added to the debt structure. A considerable part of the population have become paupers but they have to be clothed and fed that the Price System might still be operated and savings steadily increased. Production slowed down. Fewer new machines for a time and a steadily increasing liquidity in the banks and financial institutions.

Today, liquidity is approaching its maximum and soon the banks, insurance companies, and financial houses will fade quietly away, except as governmental institutions. They cannot earn enough to pay their overhead and must go into voluntary liquidation or they will fail. Any industrialist that does not modernize his equipment (and that means mechanize) must shut up shop. With an ever increasing velocity the Price System approaches its inevitable end. The Price System is a gigantic debt system and the cancellation of debt is but the foundations of that System crumbling into dust. It is wisdom to make your choice now, before you come to the parting of the ways. Then it may-be too late. Which will you have? Chaos or Science? Scarcity or abundance? Disorder or order? Death or life? The choice is yours; but the necessity for the choice cannot long be delayed. Technocracy alone, offers life.

Note this was written in 1938 when automobile production, called Fordism, was rapidly industrializing America as it is now doing in China and has done in the newly developing industrial economies of Korea and the post war development of Japan.

And speaking of Ford he already introduced the idea of increased wages for less work with his new mode of production, of course to encourage increased consumption of his product, and to control his workers by keeping the unions out.

We now face a political economy of outsourcing and contracting out work, flexible working conditions where you are expected to 'multi-task', which is deskilling of the workforce yet making us pliable for being multi use cogs in the machine of capital production. And yet we still have unemployment, and we are working more for less, and for longer hours.

Yet the society in which we live could provide abundance for all. Strange that.

As Dr. Marx points out in his work the Grundrisse, as automation increases, and allows for greater freedom of the worker, the capitalist system cannot adapt fast enough forcing the workers to give up their lesisure time, in favour of either wage slavery or unemployment.

Surplus value in general is value in excess of the equivalent. The equivalent, by definition, is only the identity of value with itself. Hence surplus value can never sprout out of the equivalent; nor can it do so originally out of circulation; it has to arise from the production process of capital itself.

The matter can also be expressed in this way: if the worker needs only half a working day in order to live a whole day, then, in order to keep alive as a worker, he needs to work only half a day. The second half of the labour day is forced labour; surplus-labour. What appears as surplus value on capital's side appears identically on the worker's side as surplus labour in excess of his requirements as worker, hence in excess of his immediate requirements for keeping himself alive. The great historic quality of capital is to create this

surplus labour, superfluous labour from the standpoint of mere use value, mere subsistence; and its historic destiny [

Bestimmung] is fulfilled as soon as, on one side, there has been such a development of needs that surplus labour above and beyond necessity has itself become a general need arising out of individual needs themselves—and, on the other side,

when the severe discipline of capital, acting on succeeding generations [Geschlechter], has developed general industriousness as the general property of the new species [Geschlecht]—and, finally, when the development of the productive powers of labour, which capital incessantly whips onward with its unlimited mania for wealth, and of the sole conditions in which this mania can be realized, have flourished to the stage where the possession and preservation of general wealth require a lesser labour time of society as a whole, and where the labouring society relates scientifically to the process of its progressive reproduction, its reproduction in a constantly greater abundance; hence where labour in which a human being does what a thing could do has ceased. Accordingly, capital and labour relate to each other here like money and commodity; the former is the general form of wealth, the other only the substance destined for immediate consumption.

Capital's ceaseless striving towards the general form of wealth drives labour beyond the limits of its natural paltriness [Naturbedürftigkeit], and thus creates the material elements for the development of the rich individuality which is as all-sided in its production as in its consumption, and whose labour also therefore appears no longer as labour, but as the full development of activity itself, in which natural necessity in its direct form has disappeared; because a historically created need has taken the place of the natural one. This is why capital is productive; i.e. an essential relation for the development of the social productive forces. It ceases to exist as such only where the development of these productive forces themselves encounters its barrier in capital itself. The Times of November 1857 contains an utterly delightful cry of outrage on the part of a West-Indian plantation owner. This advocate analyses with great moral indignation—as a plea for the re-introduction of Negro slavery—how the Quashees (the free blacks of Jamaica) content themselves with producing only what is strictly necessary for their own consumption, and, alongside this 'use value', regard loafing (indulgence and idleness) as the real luxury good; how they do not care a damn for the sugar and the fixed capital invested in the plantations, but rather observe the planters' impending bankruptcy with an ironic grin of malicious pleasure, and even exploit their acquired Christianity as an embellishment for this mood of malicious glee and indolence. They have ceased to be slaves, but not in order to become wage labourers, but, instead, self-sustaining peasants working for their own consumption. As far as they are concerned, capital does not exist as capital, because autonomous wealth as such can exist only either on the basis of direct forced labour, slavery, or indirect forced labour, wage labour. Wealth confronts direct forced labour not as capital, but rather as relation of domination [Herrschaftsverhältnis]; thus, the relation of domination is the only thing which is reproduced on this basis, for which wealth itself has value only as gratification, not as wealth itself, and which can therefore never create general industriousness. (We shall return to this relation of slavery and wage labour.)

It is time to take back our time from the machine, not through reforms like increased paternity leaves paid for out of EI, but in actual time to be with our families and friends by reducing our work time. Not adapting to flexible organisation of the workplace, where we 'job shre', that is share our poverty, our waged work. But rather the fight for the 4 hour day in the 4 hour week for 40 hours pay, is not a utopian ideal but a radical demand upon the system of capitalism.

Capital adapts such demands with its illusionary flexible working conditions for the professional classes. These are based on salaried wages, and give the illusion of a beneficient and paternalistic management in the workplace. In reality it is NOT the reduction of work time, nor its radical transformation into playtime. It is simply the sharing of surplus value time, at our own expense.

Or in the case of working from home, here the benefits of daycare, etc. are absorbed by the worker, costs that would normally acrue to the capitalist and his state.

Just as in self employment, the very basis of the wage slavery of the mercantile classes, which includes trades men, white collar managers, owners of fast food franchises, etc. the classic petit-bourgoise, here we now have the contracting out and privatization of public sector jobs to a sector that now must pay the burden of benefits and insurance, and pensions, out of their own pocket with not employer contribution. Hence most don't and end up destitute later on due to accidents, health problems, or catastrophic personal financial burderns. Thus the self employed are the self deluded, thinking they are no longer wage slaves.

This is one of the consequences of downsizing. The other is the quick capitalization and valorization of the business as the workers are disposed of but their surplus value is kept. Wages, benefits, pension funds, all are disposed of as liquid capital, which is why after downsizing corporations see their share price rise on Wall Street. Regardless of the socio economic grouping that gets laid off, waged employees, salaried employees, white collar, blue collar, support staff, production staff, distribution staff, or management.

All are one class; the wage slaves to the machine of capital.

New Study Reveals One in Three Americans Are Chronically Overworked

Triggers for Overwork and Solutions for Workplace Stress are Explored

Key Study Data

- One in three American employees are chronically overworked.

- 54 percent of American employees have felt overwhelmed at some time in the past month by how much work they had to complete.

- 29 percent of employees spend a lot of time doing work that they consider a waste of time. These employees are more likely to be overworked.

- 79 percent of employees had access to paid vacations in 2004.

- More than one-third of employees (36 percent) had not and were not planning to take their full vacation.

- On average, American workers take 14.6 vacation days annually.

- Most employees take short vacations, with 37 percent taking fewer than seven days.

- Only 14 percent of employees take vacations of two weeks or more.

- Among employees who take one to three days off (including weekends), 68 percent return feeling relaxed compared with 85 percent who take seven or more days (including weekends).

- Only 8 percent of employees who are not overworked experience symptoms of clinical depression compared with 21 percent of those who are highly overworked.

Study: Reducing hours isn’t always a career killer

By Kathy Gurchiek

Choosing to cut your workload to three or four days a week is not a career killer for top-level employees, according to Crafting Lives that Work: A Six-Year Retrospective on Reduced-Load Work in the Careers and Lives of Professionals and Managers, a study that was released Feb. 16. 2005

“Many leading employers have been formally and informally offering alternative work arrangements such as reduced-load work for many years,” according to the executive summary of the report by McGill State University, Canada’s leading research-intensive university, and Michigan State University (MSU).

“However, little research has been conducted on how choosing to use these new ways of working affects individuals, their careers, and their families over time.”

The study followed up with 81 of the original 87 salaried, nonunionized participants interviewed in 1996 to 1998 who voluntarily cut back from full-time to part-time status at 43 companies in the United States and Canada. Ages ranged from 33 to 58. Men were included, but most participants were women, and the typical one was 45, married, a manager, and had reduced her workload to 66 percent of full time.

Nearly half of those working part time were still doing so six years later, and most of those no longer working a reduced schedule wanted to return to it, according to the study, funded by the nonprofit philanthropic Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

In addition, it found that a significantly higher percentage of those working reduced work schedules had elder care responsibilities, family health problems or major personal health problems compared to those working full time. A high commitment to family and the need or desire to spend time with their children were the reasons why more than half of the participants continued working a reduced schedule.

Timesizing versus Downsizing

we address the two biggest questions of our times:(1) When introducing technology, how, without makework, can CEOs avoid downsizing employees & the consumer markets they represent? (2) Then how do we shift from maximizing consumption to save the economy, to minimizing consumption to save the planet?

Two answers, two 'gears'. (1) Timesizing = trim workweeks, not workforce & consumer base; make not taxpayer-support but self-support easier; re-employ & re-activate all marginalized consumers. (2) Once everyone is included in the worksharing system, economic growth becomes optional instead of desperately needed, because for the first time growth can be limited without starving the now well-employed 'poor'. So we then cut the workweek further to downshift production & consumption and "save the planet," that is, ecosystems and the whole biosphere.

The big picture & the-time-trilogy

The big picture & the-time-trilogyWe had a lot of help, but not from standard economists. They hate people like us. We're mavericks. Most of us are indeed dreaded "autodidacts" - self-taught people with no particular stake in any particular economic conclusion - except that maybe our whole economic juggernaut could be a lot more "win-win" than it is. Charlie Kindleberger, despite being personally a nice Ray Bolger-type of guy and a bit of an outsider himself (an American historical economist is a rare bird), said, with reference to Jane Jacobs, "All of us hate these autodidacts." (Warsh, Economic Principles, 396.) One of us autodidacts didn't get translated into English for 162 years (Sismondi).

OK, part of our problem is that we're not win-win with standard economists. We badmouth them. Jane Jacobs says economics is a "fool's paradise" and what's needed now is a wholesale rethinking of the field, a "trip back to reality." (Warsh, 396.) Joan Robinson called economics a branch of theology! And Sismondi opposed economic systems and all forms of dogmatism. But let's face it, standard economists deserve it.

We discovered that over the years, indeed the centuries, there were other autodidacts and mavericks who went over much of the same ground as us ("us" is maverick-correct here, an English disjunctive attested in Chaucer) and they laid down a pretty good foundation. In the last 20 years, Ben Hunnicutt. In the 1950s, Nobel-reject John Kenneth Galbraith. Art Dahlberg and Ed Filene in the 1930s. Lord Leverhulme (a "Lever Brother") and Stephen Leacock (a Canadian Mark Twain) in the nineteen-teens. Thorstein Veblen in the 1890s. Jean-Charles Sismondi in the early 1800s and Sir William Petty in the 1600s - see our bibliography. There are probably a lot more but they're tough to find because the mainstream does little or nothing to publicize them. None of these people get Nobels. Guess they make in-the-box thinkers uneasy. Kindleberger went on to say, "We are in the business of teaching people, and we want them to learn our stuff, not make it up." Sounds like primitive territoriality.

Another Canadian Site is:

Welcome to the TimeWork Web: the limitation of the working day is a preliminary condition without which all further attempts at improvement and emancipation must prove abortive.

And of course they have created a Workless Party, Parteee..the site is located in BC which is a wonderful land to want to work less in and play more.

I could party for that.

"Workers of the world - RELAX !!!!"

Work Less Party

Work Less, Consume Less, Live More!!!

240-Minute Man

Gabe Sinclair Has Seen the Future, and It Includes a Four-Hour Workday

By Michael Anft

Baltimore City Paper: 240-Minute Man (March 21 - March 27, 2001)

THE IDEA

At the beginning of the last century, the tractor and the assembly line revolutionized the American economy. The eight-hour workday and the forty-hour week soon prevailed as a natural consequence of these innovations.

The computer and other minor miracles have since opened glorious opportunities for a further reduction of our drudgery, yet nothing of the kind has happened. Modern life remains a headlong rush into long commutes, two-income families, late nights at work, and exhausting recreation. How could this be? What is it about our collective personality that drives us over this cliff of endless rat race?

The Four-hour Day Foundation exists to assemble a particular coalition of people prepared to question the fundamental assumptions of how we labor and how we distribute our immense wealth. Two percent of Americans now grow all of our food and then some. Another thirty million or so do all the mining, manufacturing, and construction. If this minority can produce our modern cornucopia, then the four-hour day is within easy reach. If we can rearrange world politics so as to honestly collaborate with other nations, anything is possib