Trevor Harrison / March 23, 2023

LONG READ

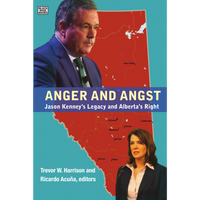

The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book, Anger and Angst: Jason Kenney’s Legacy and Alberta’s Right, edited by Trevor Harrison and Ricardo Acuña. At this book’s heart lies an account of how the United Conservative Party has governed; and the ideas, personalities, and social forces that have driven its agenda. The editors argue that an entrenched elite, based largely in the oil and gas sector, is increasingly fearful of losing its power; fearful, more broadly, of the province that Alberta is struggling to become.

Election night in Alberta April 16, 2019. Jason Kenney looked out on the gathering crowd of United Conservative Party supporters, and it was good. His supporters were loud, even ecstatic, if still angry, despite the party’s overwhelming victory: 63 of 87 seats and nearly 55 percent of the popular vote.

Kenney smiled broadly, basking in the belligerent energy. And why shouldn’t he? More than anyone else, this victory was his. Over the two previous years, he had knit together Alberta’s disparate conservative elements to defeat Rachel Notley’s New Democrats. Four years earlier, Notley’s “outsiders” had stolen the crown, a crown—as Kenney repeatedly implied—properly worn by conservatives. The NDP was, in the dismissive words used by its opponents, “an accidental government.”

Fomenting a fortress mentality in Alberta has long served conservative’s political interests. But the degree of anger directed at the province’s perceived enemies rose to new heights in the years after 2015, surging throughout the 2019 campaign, and finally consuming the party itself in the years after taking office.

Kenney stoked feelings of grievance, victimhood, and alienation, while offering himself up as a strong and decisive leader who would take on and win against the demonic forces attacking the province. Righteous vengeance would soon be visited upon Alberta’s enemies, within and without: teachers, labour unions, academics, environmentalists, Québec and British Columbia, the big city mayors—but especially, the federal Liberals led by Justin Trudeau, son of the long dead, but still despised, Pierre Trudeau.

The grievous accident of the NDP’s victory had now been redressed. For the moment, at least, the universe seemed once more to spin on its natural axis. Yet, three years later, Jason Kenney resigned as premier, rejected not only by the wider public but also half of UCP members. The leadership race that followed laid bare for all the public to see the party’s internal divisions. The election of Danielle Smith as party leader and premier in October 2022 papers over these divisions, while opening up even larger fault-lines in the province. The crisis grows.

This book examines critically the extraordinary years of the UCP’s time in office, 2019-2023; a period arguably the most chaotic in Alberta’s political history, challenged only perhaps by William Aberhart’s Social Credit during the immediate years after 1935. Inevitably, Jason Kenney and COVID-19 cast a large shadow over the story and are recounted in the chapters that follow, whether as foreground or background. But they are not the entire story, and then only a surface one. We argue the UCP’s problems of governance are a symptom of a long-term illness afflicting Alberta’s body politic, one nurtured by a political elite. Kenney, Smith, and the UCP could not have arrived on Alberta’s scene separate from a set of historical and material conditions.

Conventional (conservative) accounts view Alberta as struggling to escape the clutches of a colonialist Confederation bent on holding the province down. Irrespective of any historical truths these accounts might hold—Western Canada was indeed founded as a colonial extension of Central Canada—we argue instead that Alberta’s larger struggle over the past several decades has been an internal one. Central to this struggle has been an entrenched elite, based largely in the oil and gas sector, that is increasingly fearful of losing its power; fearful, more broadly, of the province that Alberta is struggling to become. Since the 1980s, the political coalition underpinning this historic bloc has been rent by a series of economic crises and broad social changes. In an effort to maintain its power, this elite has constructed an elaborate mythology based on a culture of grievance and victimhood. Both Kenney’s electoral victory in 2019 and Smith’s leadership win in 2022 successfully employed appeals to these myths. But while useful as a short-term, cynical, political tactic, it is a major obstacle to dealing with Alberta’s deep economic and social divisions, and to efforts to become a functioning democracy.

The Conservative Party’s long descent into dysfunction

When it was defeated in 2015, Alberta’s Progressive Conservative Party had been in office just short of 44 years, surpassing its Social Credit predecessor which had governed for a then-record 36 years. While travelling under the same name, the PCs had changed a great deal over that time in response to internal party dynamics, external pressures, and profound social changes within Alberta itself.

Peter Lougheed’s PCs, elected in 1971, were a collective of young, urban—and urbane—politicians. They heartily disliked Social Credit’s overt religiosity, parochial thinking, and rentier attitude to economic development. The Lougheed government sought to modernize Alberta through state-driven investments. The OPEC crisis of 1973 provided the financial heft necessary to meet these aims.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 at first provided a further boost to Alberta’s Treasury. Lougheed had famously argued that Albertans were the owners of the resource, and deserved a fair share of the revenues, at least 35 percent. The prospect of US$100 per barrel oil made PC politicians and oil producers drool with anticipation.

In a world dominated by oil scarcity and restricted options, higher prices are a good thing for oil producers, oilfield suppliers, and labourers. But they are a decidedly bad thing for consumers and manufacturers faced with rising inflation, and employees not tied to the industry’s fortunes. In order to ward off a potentially massive destabilization of Canada’s economy—boom in one region, bust in another—Pierre Trudeau’s federal Liberal government introduced the National Energy Program which set a ceiling, but also a floor, on the price of energy, while encouraging Canadian ownership of the oil and gas industry, as well as resource exploration and conservation. But the Lougheed government, and those of other oil producing regions, complained the program trod on provincial jurisdiction.

As the economy declined, public anger also increasingly focused on the Alberta government. Amidst eroding support, and growing populist anger, Lougheed stepped down in 1984, and was succeeded by Don Getty. Getty attempted to revive the economy through a combination of public sector austerity, direct investments in diversification, and loans to business. The oil and gas sector remained favoured, however, in the form of subsidies, foregone taxes, and reduced royalty rates. Where the Alberta government had previously operated with a modicum of control over the oil industry, the situation was now reversed. The economy’s dependence upon the oil industry was replicated at the political level by the PC’s growing dependence upon the same industry to remain in office.

The Getty government’s efforts at diversification failed spectacularly, leaving Alberta taxpayers on the hook, and putting to an end—at least for a time—notions of direct government ownership. Getty resigned the fall of 1992, amidst another economic downturn.

On the political ropes, the Progressive Conservative party morphed into a new version of itself. The party anointed a new leader, Ralph Klein. Klein’s populist appeal resuscitated the party’s fortunes. His party rode to victory in 1993 on one of Alberta’s now recurrent waves of anger, and a platform of harsh austerity. The Klein government adopted en masse the emergent neoliberal orthodoxy of privatization, deregulation, low taxes, and small government. The mantra of small government and low taxes was music to the ears of Alberta’s entrenched corporate elite, but also found support among conservative rural voters.

How long Albertans would have tolerated a ratchetting down of provincial services and the wholesale selling off of public assets, we will never know. Within two years, the price of oil and natural gas rebounded. Budget surpluses of $7-10 billion per year became an annual, and anticipated, event, like the coming of Christmas. Flush once more with money, the Klein government was able to assuage discontent while claiming a wholly unearned reputation for fiscal competence. A political catchphrase—“The Alberta Advantage”—was coined alleging the province’s wealth was a product of low tax rates, and not the reverse. The day of reckoning for both the party and Alberta’s finances was thus put off a little longer.

Klein’s disinterested and increasingly desultory performance as premier came to a head in 2006. He resigned after delegates to the party convention gave him a less than overwhelming show of confidence. The search for a successor began. Alberta’s corporate leaders viewed only two candidates as acceptable: Jim Dinning and Ted Morton, both former Alberta finance ministers, both Calgary-based. In a surprise vote, however, the party’s rural constituents threw their support behind Ed Stelmach, an unassuming MLA from the farming community of Vegreville, north-east of Edmonton.

The 2006 PC leadership race happened at the height of one of Alberta’s most significant oil booms. Inflation was running rampant, small and large businesses were having difficulty finding or affording staff, and the gap between the outrageous profits of the oil companies and provincial revenue from royalties was astounding, even for Albertans; so much so, that the issue of reviewing royalty rates became an important part of debates and discussions during the race. Stelmach promised that, should he become premier, he would take steps to ensure Albertans were receiving a fair share of oil wealth in the province. That promise boosted his fortunes, and helped him win the leadership.

Soon after taking office, Premier Stelmach launched a royalty review. That review recommended some significant changes to the structure and amount of provincial royalties. Faced with an aggressive campaign of protests, lobbying, and electoral threats, Stelmach stopped short of fully embracing the panel’s recommendations. He did, however, make some moderate changes that made royalty rates more sensitive to oil prices than they had been in the past. Despite Stelmach’s compromise, the oil industry was apoplectic and decided to send him a message. It found a messenger in the form of the Wildrose Alliance Party of Alberta, a right-wing fringe party founded in early January 2008 from remnants of several other fringe parties. Corporate donations to the Wildrose Alliance surged, especially during the 2008 provincial election.

But for the Great Recession that began in 2008, Stelmach’s PCs might have weathered the discontent. At first, Alberta seemed to escape the worst impacts of the crisis, but the recession caused a downturn in global oil consumption, resulting in a drop in Alberta’s revenues. In the spring of 2009, Stelmach’s government announced it would run a record deficit for the year. Despite the fact the new royalty regime only kicked in on January 1, 2009, at which point, due to low prices, no one in the province was paying higher royalties than they had the day before, Alberta’s petroleum industry blamed the new royalty regime for the deficit. No government since, including the NDP, has seriously attempted to raise royalty rates on oil and gas.

There are two political certainties arising from any economic downturn in Alberta. First, many Albertans will turn their anger against a grab-bag of perceived enemies, mainly the federal government and Central Canada elites, resulting in the rise of populist parties and protest movements. Second, Alberta’s governing coalition will unravel, giving rise to internal protest movements or third parties upset with their own government. Pummeled politically from all sides, Stelmach stepped down in October 2011.

Once again, Alberta’s corporate elite had its choice as successor: Gary Mar, a career politician who had held numerous posts in the Klein government and had strong business connections. But, instead, a newly-minted MLA, Alison Redford, cobbled together a coalition of urban liberals and progressives to win the leadership. The coalition held together long enough to defeat the Danielle Smith-led libertarian-populist Wildrose party in the April 2012 election that followed, but a fault-line had emerged in the broader conservative coalition. While the PCs won, taking 61 seats, the Wildrose party took 17 seats, mainly in rural Alberta. More worrying for the PCs, the party garnered only 44 percent of the vote compared to Wildrose’ 34 percent, a fissure that grew larger over the next year. Redford already had little support within caucus, which had favoured Mar. The knives quickly came out after a series of political blunders saw her poll numbers fall to Stelmach-like levels.

Redford’s resignation in March 2014 sent the PCs once more searching for a saviour. He was found this time in the person of Jim Prentice. Prentice was a prominent Conservative MP who had held several distinguished ministries in Stephen Harper’s government. Prentice exuded something of the aura of Lougheed. He promised a new style of politics, one that would be honest and devoid of scandal. Above all, he promised to heal the split on the right between the PCs, Wildrose, and other fringe elements.

In December 2014, Prentice and Smith made a secret agreement whereby she and eight other Wildrose members crossed the floor to join the PCs. Far from being a brilliant political maneuver, many Albertans—Wildrose supporters in particular—viewed the unprecedented action as an example of cynical and corrupt politics. Both Prentice’s and Smith’s lustre dimmed, while the remainder of the Wildrose faction held firm under a new leader, Brian Jean, a former Conservative MP from Fort McMurray-Athabasca. The subsequent election of May 5, 2015, saw Rachel Notley’s New Democrat’s take 54 of 87 seats (nearly 41 percent of the vote), compared to 21 seats (24 percent) for Wildrose, which had rebuilt itself under a new leader, Brian Jean, and nine seats (28 percent) for the PCs. Prentice immediately resigned as party leader.

The New Democrat Interregnum

To paraphrase Marc Antony (via Shakespeare), the alleged harm that governments do is later repeated ad nauseum by their opponents, while the good they do is later forgotten, erased, or adopted without attribution. Reviewing the NDP’s time in office, Ricardo Acuña termed the NDP the most “activist government in recent Alberta history,” yet far from radical. Among its first acts, the new government banned corporate and union donations to political parties, replaced the 10 percent flat rate tax with a progressive tax featuring four new rates, and approved interim spending in the key areas of health, education, and social services. Though facing an enormous drop in revenue, due to shrunken oil prices, it declined to slash public services, and later increased the minimum wage to $15 per hour—fairly standard Keynesian practices during a recession. The new government also revised the Alberta Labour Relations Code and the Employment Standards Code, created Alberta’s first ministry for the status of women, increased funding for women’s shelters, introduced a pilot project for $25-a-day daycare, and introduced protections for gay-straight alliances in schools.

The NDP’s time in office was not without controversy. Though there were no major scandals, and little discord—Notley ran a tight and focused ship—there were policy mistakes and errors in judgement. An effort to extend occupational health and safety provisions, and WCB coverage, to farm workers failed to adequately consult the farming community. Following a review headed by the former head of ATB Financial, the government did not raise oil and gas royalty rates, a decision that confused and angered many of the party’s supporters. While the party’s climate plan had some bold elements—the accelerated phasing-out of coal-fired plants to 2023, setting an absolute cap on oil sands emissions, and introducing a carbon levy—the energy sector’s usual suspects condemned it as going too far, while some party supporters complained it did not go far enough. Finally, the NDP’s policies on long-term care proved inadequate during the pandemic of 2020-22.

Dealt a difficult hand, Notley’s NDP was a generally moderate and capable government. Arguably, it was similar to the early Lougheed PCs (the latter was more leftwing on economic policy, for example, in enacting public ownership of key sectors, as in the case of Pacific Airline, but less supportive of labour). Both Lougheed and Klein benefited from rapidly rising oil revenues early in their terms, but Notley’s government received no such advantage. The price of Western Canada Select oil remained low throughout her term. Her party received no credit either for holding Alberta steady in the face of the resultant rise in unemployment and provincial debt. Once again, despite the fact that oil and gas markets are global, and that the oil sands in particular are a less attractive long-term financial investment, radio talk shows and Postmedia–which owns all of Alberta’s major newspapers—blamed the province’s difficulties on socialism, an epithet directed not only at the NDP but previous Conservative governments. The anger provoked by social media and politicians found its apogee in physical threats made to Notley and several of her cabinet ministers, especially women MLA’s, requiring the RCMP to provide police protection. As during past economic downturns, conspiracy theories flourished.

In late 2018, a few hundred yellow-vested protestors, drawn primarily from the oil and gas sector, took to Alberta’s streets. The orchestrated protests gained traction just before Christmas when some of the same yellow vests joined a convoy of 1,200 trucks, driven by oil patch workers and their supporters, that had assembled in the town of Nisku, just south of Edmonton. Blocking traffic as they went, the convoy drove slowly to the capital, making known as they did their demand that oil pipelines be built to “free” the resource from its land-locked status. The spectacle gave birth three days later to similar pro-pipeline protests in other Alberta towns and cities, including Calgary, Brooks, Edson, Grande Prairie, and Medicine Hat. Hopping the provincial border, a trucker protest also took place in Estevan, Saskatchewan that same day. The protests were a dry run for the Freedom Convoy occupations of Ottawa and several border crossings in early 2022.

While blocked pipelines were the immediate cause of fear and loathing, the narrative echoed a familiar search for enemies who—so the argument goes—are bent on keeping “the West” in perpetual servitude. Similarly, the NDP’s introduction of a carbon tax, a measure recommended by most economists, including those of a conservative bent, further added to a chorus of theft orchestrated by external enemies. Despite its aggressive and unapologetic cheerleading for pipelines and for the oil industry—a stance much criticized by many of its own supporters—the NDP continued to be blamed for its handling of the economy and for simply being the NDP. For many conservative voters, the NDP was merely one of a host of usual enemies, the federal Liberals, and Quebec, to which some now added Canada’s Supreme Court and the United Nations, attempting to take away Alberta’s economic and political birth-right.

The protesters’ arguments were rarely coherent, and often contradictory; anger, the common glue. The protesters received sympathetic support from some high-profile individuals, like Danielle Smith, Ted Morton, and University of Calgary economist, Jack Mintz. But the rallies also frequently attracted members of far-right hate groups, such as the Proud Boys and the Soldiers of Odin. A whirlwind of anger and angst swept the province.

Yellow vest protesters in Calgary, January 2019. Photo by Gabrielle Pyska.

Re-uniting the right

To say that Alberta conservatives were stunned by the New Democrat win in 2015 is an understatement. Not only was Alberta viewed as a safely conservative place provincially, since the late 1980s it had also been the beachhead for the New Right’s transformation of conservatism federally. Through first the Reform Party and later the Canadian Alliance Party, the New Right in 2003 had orchestrated a hostile takeover of the Progressive Conservatives. With the exception of a few urban ridings, the rebuilt federal Conservatives could count on winning—often without bothering to campaign in the province—nearly every Alberta seat. The 2015 provincial election shook this confidence. If the NDP could win provincially, might the federal party’s hold on the province also be waning?

It was comforting for conservatives to believe the NDP’s victory was the result of vote-splitting between Wild Rose and PC supporters, and not deeper social and political changes occurring within the province. The solution was thus to broker a marriage between the conservative factions, a solution for which there was already a blueprint: the merger/takeover of the federal Alliance and Progressive Conservative parties fourteen years earlier. A prominent federal politician, Jason Kenney, played a major role in that event.

As the party had when it welcomed a prominent federal Conservative, Jim Prentice, in 2014, Alberta’s conservative brain-trust turned to Kenney in its hour of desperation. It had long been thought he harbored ambitions of succeeding Stephen Harper as federal Conservative leader, a belief that grew following the latter’s resignation after the party’s defeat in the fall 2015 election. Instead, Kenney announced in July 2016 that he would run for leadership of Alberta’s Progressive Conservatives. He seemed an inspired choice. He had the kind of background that spelled “winner.”

Like many prominent Alberta conservative politicians, Kenney was actually born elsewhere — Oakville, Ontario in 1968—though raised in nearby Wilcox, Saskatchewan. He graduated from Athol Murray College of Notre Dame, a private Catholic High School (he remains a devout Catholic). Kenney later attended St. Michael’s University School in Victoria, BC, and still later the University of San Francisco, a Jesuit-university where he was attracted to the ideas of prominent neo-conservative theorists. He became a noted anti-abortionist and opponent of Gay rights and free speech on campus, but left after one year without completing a degree. Kenney is a “movement conservative,” meaning that he sees the role of government being to radically transform society; in the case of Alberta, following an ideologically-driven agenda of corporatism mixed with social conservatism.

Still in his early twenties, Kenney got a job as executive assistant to Ralph Goodale, the Saskatchewan Liberal party’s leader at the time. He soon left, however, to become the Alberta Taxpayer’s Federation’s first executive director, followed the next year (1989) by being named president and chief executive of the newly minted Canadian Taxpayer’s Federation. In his role with the CTF, Kenney made a name for himself in a shouting match with then Alberta Premier Ralph Klein in 1993 when he confronted Klein over MLA’s “gold-plated pensions.” Facing an election, Klein relented; days later, the pension plan was eliminated. Kenney’s political star was ascendant.

In 1997, at the age of 29, Kenney was elected to the House of Commons as a member of the Reform Party for the riding of Calgary Southeast. Three years later, he became chief advisor and speech-writer for Stockwell Day during Day’s successful bid for the leadership of the Canadian Alliance party. Kenney remained a key Day supporter and alleged speech-writer during the Alliance party’s much less successful federal election campaign that same year.

To a remarkable degree, Kenney’s political trajectory and later problems mirror that of Day’s rise and eventual fall, which paved the way for Stephen Harper taking the Alliance party’s helm in the spring of 2002, and a year-and-a-half later becoming leader of the newly-formed Conservative Party of Canada. By this time, Kenney had established himself as a loyal foot-soldier for the party.

Like Harper, Kenney was a vocal supporter of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 and remains an equally staunch supporter of Israel. Known for his dedication and hard work, it was expected that Kenney might be given a cabinet post when the Conservatives won office in 2006, but Harper instead assigned him the task of building party support within the ethnic communities. That community was traditionally viewed as part of the Liberal support base due to its long-established support for immigration, but many conservatives viewed the religious background of many immigrants as fertile ground for recruitment. Kenney took on the task of political conversion with enthusiasm and some success.

Now, in 2016, Kenney—the prototype of a career politician—was called upon to take on another task: to re-unite Alberta’s conservative factions and thus save the party—and the province—from the socialist threat. The task proceeded with military precision. Kenney declared he would run for leadership of the PC party. Given his existing profile, and the fact the demoralized PCs were devoid of any genuine challengers, he easily won the leadership the following March.

Following brief negotiations, Kenney and Brian Jean agreed upon a plan to unite the PC and Wildrose parties. In July 2017, members of both the Progressive Conservative and Wildrose parties voted overwhelmingly in support of a merger. The leadership race quickly followed.

Despite Kenney’s credentials, it seemed at least possible that Jean might defeat him. A ThinkHQ poll released in May 2017 showed that Jean was heavily preferred over Kenney by Albertans and that Jean held a substantial lead even among likely UCP voters.

The leadership race was bitter. Kenney, like Dinning, Mar, and Prentice before him, was the establishment candidate; Jean was the candidate of the rural populists. Rumours of dirty tricks by the Kenney team abounded, rumours that continued to dog the party in the years that followed. But, on October 28, 2017, Kenney secured an easy first ballot victory over Jean to take the UCP leadership. The final tally showed he took 61 percent of the vote to Jean’s almost 32 percent, with third place finisher Doug Schweitzer taking just seven percent. Kenney’s path to the premiership was set.

Conservative voters in Alberta like a winner, and Kenney seemed best positioned to deliver victory. Besides his political background in federal politics, Kenney—as described by journalist Don Martin—was “brilliantly analytical,” “fiercely articulate,” “flawlessly bilingual,” and “tirelessly energetic,” while keeping “his social conservative beliefs under a kimono that’s never to be lifted.”

Even at that time, however, many UCP party supporters had concerns about Kenney. They viewed him as something of an outsider, even a carpetbagger, insufficiently disposed to grassroots democracy. It was widely believed that he was simply using Alberta as a launching pad for his federal ambitions. In a province, moreover, whose political culture embraces genuineness, Kenney seemed profoundly inauthentic. He was clearly uncomfortable wearing a cowboy hat or sitting in the cab of a Ford F-150. While he talked endlessly about “the people,” he did not seem one of them.

For the moment, however, any such concerns were set aside. Over the next year and a half, Kenney travelled the province polishing his and the party’s profile. In his speeches, Kenney gave no quarter. Alberta was beset with enemies, both within and without, but he would slay them. A vote for the UCP meant a return to prosperity. A majority of Albertans believed Kenney’s promises.

The UCP’s victory came as conservatism in Canada was reaching its high-water mark. Following the spring 2019 election, six of Canada’s ten provinces were led by Conservative governments, including not only Alberta, but Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. Only months earlier, in December 2018, the cover of Maclean’s showed Rob Ford, Brian Palliser, Jason Kenney, and Scott Moe, bracketing federal leader Andrew Scheer, under the title, “The Resistance.” The sunny ways of Justin Trudeau’s victory four years earlier had given way to growing clouds, giving conservatives hopes of having another powerful ally in confronting Ottawa.

But the UCP’s relatively easy victory in 2019 papered-over some hard realities that Jason Kenney’s self-satisfied smile on election night could not hide. Kenney returned to an Alberta of his imagination; indeed, one that conservative elites, comfortable in their idea of the province’s unchanging nature, had not taken time to recognize or understand. Kenney returned to an Alberta that is largely urban, young, and socially liberal; an Alberta that, if fitfully, is trying to come to terms with the decline of oil and gas dependency; an Alberta in which issues of climate change and Indigenous rights increasingly hold centre stage; an Alberta where even rebounding oil prices are no guarantee of increased employment; and an Alberta that would soon face a pandemic that shook the province’s economy and conservative notions of small government, even as it drove a spike down the centre of definitions of what “is” conservatism.

The United Conservative Party takes the reins

The UCP quickly appointed a cabinet. It consisted of 22 members (seven women and 15 men). A dearth of elected members from Edmonton meant a severe over-representation of Calgary MLAs in cabinet. While the next few years saw the cabinet’s expansion, frequent recycling, and some departures, the key members of that first cabinet—those whom Kenney trusted—remained largely in place throughout. Those key members included Kenney’s former leadership opponent, Schweitzer (Calgary-Elbow), a lawyer, appointed to the ministry of justice and solicitor general; Tyler Shandro (Calgary-Acadia), a lawyer, minister of health; Ric McIver (Calgary-Hays), a former Calgary counsellor, minister of transportation; Adriana LaGrange (Red Deer-North), a Catholic School division trustee and rehab practitioner, minister of education; Travis Toews (Grande-Prairie-Wapiti, an accountant, minister of finance; Jason Nixon (Rimby-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre), non-profit sector, minister of environment and parks; Sonya Savage (Calgary North-West), oil and gas executive, minister of energy; Demetrios Nicolaides (Calgary-Bow), communication background, minister of advanced education; Jason Copping (Calgary Varsity), lawyer, minister of labour and immigration; Rebecca Schulz (Calgary-Shaw), minister of children’s services; and Kaycee Madu (Edmonton-South West), lawyer, minister of municipal affairs. Of these key ministers, LaGrange, Toews, Nixon, Nicolaides, Schulz, and Savage held their posts throughout the UCP mandate. A few played musical ministries; Schweitzer, Shandro, and Copping, in particular. Others, for reasons of scandal (Devin Dreeshen, minister of agriculture and forestry, and Tracy Allard, minister of municipal affairs) or disloyalty to Kenney (Leela Aheer, minister of culture, multiculturalism, and status of women) were dropped.

The UCP’s first hundred days in office saw a whirlwind of legislation designed to polish the government’s activist agenda but also to erase, in policy if not memory, all traces of the NDP; for example, reversing changes to Alberta’s labour laws. Much of the legislation (repealing the carbon tax, declaring Alberta open for business, reducing red tape, restoring the election of senators) was meant to appeal to the UCP’s base. Several other measures were directed at the party’s supporters in the corporate sector; for example, a drop in corporate taxes, later speeded up, from 12 to eight percent. The energy sector, in particular, was assisted by allowing municipalities to give property tax exemptions to energy companies and guaranteeing that no changes to the oil and gas royalty structure would occur for ten years. In a measure directed at its social conservative base, the government amended legislation regarding gay-straight alliances in schools and embarked on a curriculum review. The new government also created a “war room”—later formally named the Canadian Energy Centre—to combat the bad press generated, in the eyes of government supporters, by anti-oil, anti-Alberta environmentalists. In the same vein, the government also launched an investigation into foreign funding received by those anti-oil, anti-Alberta environmentalists for the purpose of “landlocking Alberta’s oil.” Much of its legislation was bathed in symbolism, as was the government’s rhetoric which, when not attacking the former NDP government, was focused on the Liberal government in Ottawa.

Kenney’s own focus on the federal Liberals bordered on an obsession, leading to renewed speculation that he viewed the premiership as a stepping stone to becoming prime minister. His hatred of the Trudeau government precluded giving Ottawa any credit, even when it provided controversial support for the TransMountain pipeline and financial assistance for cleaning up orphan wells; or provided Albertans with more financial support per capita during the COVID-19 pandemic than given to people in any other province—$11,410 per person, compared to Ontario, the second highest, at $9,940. Kenney’s reluctance to engage with the Trudeau Liberals often harmed Albertans, as when his government refused for nine months to participate in a cost-share agreement with Ottawa to provide a one-time payment of $1,200 to frontline workers or to participate in the federal government’s national child care program. Beyond personal animus, ambition, or stubbornness, however, Kenney’s relentless attack on the federal Liberals played well with the UCP’s base, reinforcing the belief they are an isolated and persecuted victim of Confederation.

The political attacks were directed not only at the Trudeau Liberals, however. The UCP also kept focused on a host of perceived enemies at home. It is traditional political practice to attack and hobble one’s real and imagined political enemies. The UCP quickly set its sights on public institutions and public sector workers within them, as well as K-12 teachers and faculty within post-secondary institutions. Remarkably, even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government continued its assault on the public health care system and its nurses and doctors whose support was essential to dealing with the crisis.

Kenney’s own pugnacious character found its echo in several ministers. Kaycee Madu, Jason Nixon, Sonya Savage, and Tyler Shandro, in particular, tended to angrily ignore criticisms and view everything through a political lens. In short order, the government made enemies not only of the usual suspects, but also ranchers (over coal development in the Rockies), farmers, municipal politicians (over EMS restructuring and policing), and doctors (cancellation of a contract). As Mueller relates, the government’s actions also increasingly alienated young people who no longer saw a future in the province. The list of organizations angry and distrustful of the government grew steadily, as did the number of pointless issues whose chief appeal was that they were favoured by the UCP’s narrow base. Scarce were the government’s major files that did not rile some group. Former allies—like the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms and conservative journalists Licia Corbella and Rick Bell—increasingly found Jason Kenney’s leadership wanting.

Alberta’s economy remained a key part of the story. The election campaign’s slogan was “jobs, economy, pipelines,” accompanied by a frequent choral background of “build that pipe, build that pipe.” But the price of oil did not immediately recover, nor did the jobs return. As in the past, the harsh realities were brought home of living in a single-resource economy, dependent upon external forces, and—for political reasons—reluctant to examine its finances. As the hopes and dreams of election night began fading, old divisions reemerged. Like topsoil in a Prairie windstorm, the idea that replacing the NDP would return Alberta to prosperity quickly vanished. By the fall of 2019, Kenney’s—and the party’s—appeal was already in decline. Over the course of three years, the party stumbled repeatedly on those areas in which it showed particular interest, such as education, energy, and health, while ignoring other important areas, such as housing and race relations, especially the rise in hate speech during the pandemic that followed. The issues of some specific groups—women and Indigenous peoples—disappeared almost entirely from the government’s agenda.

In the midst of everything, COVID-19 came along. The two years from spring 2020 until spring 2022 saw infection and death rates soar throughout much of the world, its variations remaining still a threat. Though Canada as a whole did better than most countries in dealing with the pandemic waves washing its shores, Alberta’s efforts proved weak, vacillating, and desultory.

From the pandemic’s start, Kenney placed himself squarely at the centre of its handling. More than any Canadian premier or even Prime Minister Trudeau, Kenney chose to dominate the COVID-19 updates, though some noticed he tended to show up only when there was good news. Early on, Kenney often held a pointer to alert viewers to numbers on a graph. Other times, he expounded on the virus’ causes, virality, and lethality. Soon, he acquired the epithet, “Professor Kenney.” Viewers sometimes wondered whether health officials, as they stepped to the podium, were left anything to say except, “What he said.”

The pandemic continued. The UCP’s handling of the pandemic, now centred on Kenney, was increasingly condemned on all sides as slow, weak, uneven, and contradictory. Many Albertans wanted tougher measures; many UCP backbenchers and supporters in rural communities, mistrustful of government and of science, wanted few, if any. The UCP, itself, manifested the split. Worse, several UCP MLA’s, including members of cabinet, were caught flaunting health care restrictions, resulting in accusations of entitlement that had brought down earlier conservative regimes. Kenney, who exuded a sense of righteous authority and resolve when denouncing Alberta’s illusory enemies, proved weak and indecisive when tasked with handling actual problems within his caucus and his own office.

As 2020 turned to 2021, Alberta’s economy still languished, the pandemic still lingered, and Kenney’s leadership leaked support. A palace revolt stirred. By spring 2021, the revolt was in full bloom.

The insurrection grows

In early April 2021, 17 UCP MLAs wrote a public letter denouncing the imposition of new lockdowns. A month later, some members openly called for Kenney to resign. Two rural MLA’s, Todd Loewen and Drew Barnes, were removed from caucus, but the action did not stem the revolt. Calls for Kenney to step down as leader grew throughout the summer and fall of 2021, with the result that the UCP ceased almost entirely to govern during the year that followed, consumed instead by internal conflicts and the premier’s efforts to hold on to his leadership.

Amidst growing internal discontent, the UCP board decided in December to move up a leadership review to the spring of 2022. Party dissidents wanted a provincewide virtual vote open to all UCP members to be held by early March. It was agreed instead that an in-person leadership review would be held at a Special General Meeting in Red Deer on April 9. On March 15, however, Brian Jean—former Wildrose leader, and co-founder of the UCP—won a byelection victory in Fort McMurray-Lac La Biche. Jean immediately called for Kenney to resign, saying that he was prepared to take on the leadership of a renewed party.

As April 9 drew closer, the vote to remove Kenney as leader gained steam. A delegate attendance in Red Deer of perhaps 20,000 people was predicted. Citing logistical problems, UCP President Cynthia Moore announced on March 23 that the in-person leadership vote was changed to a mail-in vote of all party members, the results of which would be announced on May 11.

Kenney was clearly rattled. In a secretly recorded speech to his party’s caucus staff in March 2022, he said he would not let “the mainstream conservative party become an agent for extreme, hateful, intolerant, bigoted and crazy views,” adding that, “The lunatics are trying to take over the asylum. And I’m not going to let them.” The leaked recording solidified opposition to Kenney among those who viewed his leadership as top-down and disrespectful of grassroots members.

On April 9, the original date for the leadership review, Kenney spoke in Red Deer to a small gathering of hand-picked supporters, recounting a litany of “promises made, promises kept” and, as he saw it, the UCP’s successes under his leadership. He warned against division, what would happen if the NDP were ever returned to power, and—by implication—the need to support him in the leadership review.

In the weeks leading up to May 11, some members spoke openly of a culture of fear and intimidation that Kenney and his staff had created within the party. Still, or perhaps because of this, many observers thought Kenney would squeak out a victory; and, in any case, would not step down as leader. But when the final votes were announced on May 11, he received only 51.4 percent support, and immediately said he was quitting as leader. Kenney later blamed his demise on “a small but highly motivated, well-organized and very angry group of people who believe that I and the government have been promoting a part of some globalist agenda, and vaccines are at the heart of that.” In the eyes of many, that explanation left out much. While there was surprise, there were few tears shed; in the backrooms of UCP detractors to his leadership, happiness reined.

The UCP’s executive decided the new leader would be chosen by a vote of party members using a preferential voting system whereby the new leader would have to achieve the support of at least 51 percent plus one of the members. The new leader would be announced on October 6. In the meantime, Kenney remained as party leader and premier. Polls showed a sudden bump in support for the UCP who—even absent a decided leader—would defeat the NDP.

The search began for a new saviour of Alberta’s dis-united right.

Danielle Smith reacts with a smile after she lost a provincial election in High River, Alberta, April 23, 2012. Photo by Mike Sturk/Reuters.

The race and Smith’s coronation

Seven candidates vied for the UCP leadership: five UCP MLA’s (Leela Aheer, Brian Jean, Rajan Sawhney, Rebecca Shulz, and Travis Toews), one independent MLA, Todd Loewan, and one unelected individual, former Wildrose leader, Danielle Smith. Despite the large number of entries, however, most observers quickly viewed the race as likely to come down to a choice of Jean, Smith, or Toews.

Each of the three had notable strengths and weaknesses. Toews had the vast support of sitting MLAs, including—though not formerly announced—Kenney, and had the cachet of being the party’s former finance minister, but was also viewed as dull and unspiring. Smith, after her political self-immolation as Wildrose leader in 2014, had rebuilt her profile as a talk-show host where she garnered a large number of loyal listeners, but also acquired a reputation for taking extremist positions. Jean, the party’s sympathetic everyman, was lauded for having saved the Wildrose party from oblivion in 2015, but like Toews was considered uninspiring. None of the others was viewed as likely to win, though some hoped Aheer, Sawhney, and Shulz might move women’s issues to the centre of debate and also encourage a more civil and collegial form of politics than exercised under Kenney.

Smith quickly seized the high-ground, setting the pace and direction for the others. She singled out Alberta’s traditional enemies, the Liberals and Central Canada (the “Laurentian elites”), but added Alberta Health Services in an appeal to her anti-vaxxer supporters; and, going even farther afield, attacked such organizations as the United Nations, the World Economic Forum (WEF), and the World Health Organization (WHO), viewed by conspiracy theorists as part of an alleged globalist agenda to replace capitalism with socialism (the “Great Reset”).

By the week of August 8, Trump-like hysteria was in full-flight. An online message sent by Smith’s team read:

[T]he WEF is an anti-democratic group of woke elites that advocate for dangerous socialist policies that cause high inflation, food shortages and a lack of affordable energy, which in turn, leads to mass poverty, especially in the developing world. There is no question what their agenda is. They want to shut down our energy and agriculture industries as fast as they can.

Conspiracy mongering aside, Smith’s most politically astute move came in the form of the Free Alberta Strategy. The strategy’s centrepiece is the Sovereignty Act, co-authored with former Wildrose MLA, Rob Anderson.

The proposed Act vaguely wavers between greater autonomy and outright secession, and reminds of comedian Yvon Deschamps’ oft quoted joke about Quebec: That all the province wants is to be independent within a strong and united Canada. Many UCP supporters believe that Alberta’s problems would magically melt away if Ottawa would just “butt out.” Encouraged by some conservative politicians, some even suggest the province, like Quebec, constitutes a nation.

Smith’s Sovereignty Act harkens back to Social Credit’s efforts under Premier William Aberhart to enlarge Alberta’s jurisdictional autonomy, efforts later ruled by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional. But like so many ideas espoused by Canada’s current conservatives—right to work, charter schools, privatized health care—the Act also echoes state’s-rights arguments in the U.S.; historically, in particular, that individual states could ignore and refuse to enforce within their borders any act passed by Congress or the Federal government which it viewed as transgressing rights reserved to itself.

Howard Anglin—a former adviser to Stephen Harper—termed the Free Alberta Strategy “nuttier than a squirrel’s turd.” Numerous journalists and constitutional experts likewise denounced Smith’s proposal as vague, unworkable, unlawful, and bizarre. Several of her leadership opponents, notably Jean, Toews, and Shultz said Smith’s proposal would create uncertainty and drive away investment.

Nutty or not, Smith’s advocacy of sovereignty separated her from the other candidates and solidified her bona fides with the party’s more extreme and angry supporters; and, further, set down a marker that pulled the party further to the right, even redefining the nature of the party’s position on the political spectrum. Smith’s six leadership opponents criticized the Act. (Jason Kenney described it as a “full-frontal attack on the rule of law,” as well as a step towards separation and a “banana republic”) Quickly, however, several candidates came out with their own proposals for greater Alberta independence. Jean proposed an Autonomy for Albertans Act that would “enhance Alberta’s autonomy within Canada.” Shultz announced her own “100 Day Provincial Rights Action Plan to fight, partner, and strengthen Alberta’s position in Canada.” Loewen called for Alberta to create its own Constitution. Loyalty tests became de rigeur.

Most of the candidates—and all of the leading ones—thus staked out positions as “Alberta Firsters.” In the eyes of many UCP’s supporters, the departing premier had lacked the intestinal fortitude to “take on” Alberta’s enemies. Of all the contenders for the UCP leadership, Smith presented as the street brawler best up for this task.

The other candidates did not go down without a fight: Each sent out repeated warnings to the membership about Smith’s past mistakes. Likewise, Kenney—fearful of what a Smith leadership might mean for the party—became increasingly aggressive in warning against a Smith takeover of the party he had welded together. A Political Action Committee (PAC), Shaping Alberta’s Future, formed originally to promote Kenney and the party, began posting in mid-September a series of ads on Facebook, Instagram, and Google questioning Smith’s qualifications and warning that her victory would likely result in an NDP win come next election.

The Sovereignty Act remained her seminal attraction. She told the audience during the party’s final official leadership debate that:

We might be facing mandatory vaccination; we will say we will not enforce that…. If there’s an emergencies act that wants to jail our citizens or freeze their accounts, we will say we will not enforce that. Arbitrary fertilizer cuts, arbitrary phaseout of our natural gas for electricity and power. Arbitrary caps on our energy industry and perhaps even a federal digital ID. [If] we have the Alberta Sovereignty Act, we will not enforce that. We’ll put Alberta first.

In other times and places, Smith’s conjuring of threats that simply did not exist might have disqualified her as a serious candidate. But nothing—neither her opponent’s criticisms nor her own inflammatory rhetoric—derailed Smith’s quest; indeed, it cemented her reputation among UCP members as a “fighter.”

Though it took six ballots, on October 6, Smith claimed the UCP’s leadership prize. The final tally saw her defeat her main rival, Toews, with 42,423 votes (53.77 percent) to his 36,480 votes (46.23 percent), a winning percentage of support only two percent more than Kenney had received in stepping down. The number of votes cast (84,593) represented only 69 percent of the party’s membership (123,915). In turn, the vote for Smith meant that 1.5 percent of Alberta’s electorate (roughly 2.8 million voters) had now put in charge of the province an unelected individual whose political past, in the eyes of many, is checkered. No matter; with Smith’s victory, Alberta’s Wildrose faction had secured the outcome denied it in 2012.

How did Smith win? As Chapman and Epp point out, it is too simplistic to describe Alberta’s electorate as divided between rural and urban constituents. Better than the other candidates, however, Smith succeeded in playing to the feelings of anger, fear, and disempowerment felt by the narrow base of UCP members. A CBC analysis of UCP members, who make up only 3.5 percent of Alberta’s population, showed a large number come from a small number of ridings south of Red Deer, and only 41 percent from the big cities of Edmonton and Calgary. Smith appealed to these members’ fears and anger, particularly around the COVID-19 mandates and resultant protests. Another study shows that, while 61 percent of Albertans disagreed with the Freedom Convoy’s goals, and 67 percent with its methods, 56 percent of UCP respondents supported its goals and 48 percent its methods.

Smith’s victory speech on the evening of October 6 echoed in many ways Kenney’s from election night in 2019. Beginning with an exuberant “I’m back!” she thanked her opponents, as well as Kenney, while encouraging party members to remain united and strong. Alberta was about to write “a new chapter” in its story, she said. “It’s time for Alberta to take its place as a senior partner to build a strong and united Canada.” But, “No longer will Alberta ask for permission from Ottawa to be prosperous and free,” continuing:

We will not have our voices silenced and censored. We will not be told what we must put in our bodies in order to work or to travel. We will not have our resources landlocked or our energy phased out of existence by virtue-signalling prime ministers. Albertans, not Ottawa, will chart our own destiny on our own terms.

Jason Kenney is a proud man. At that moment, he must surely have wondered about his legacy — or, perhaps, competing legacies, neither of them to his liking. In the immediate term, Danielle Smith is a renegade libertarian who could well destroy the party he founded; in the longer term, Rachel Notley and the NDP may return to office, an outcome which he had come to Alberta to prevent. Other conservatives likewise observed warily what had transpired and the future laying ahead. In the words of long-time advisor Ken Boessenkool, “Premier Smith is a kamikaze mission aimed at the UCP, conservatism and Alberta.”

On November 8, Smith won a byelection in Brooks-Medicine Hat, taking 55 percent of the vote, compared to 27 percent for her NDP and 17 percent for her Alberta party opponents. It was not an overwhelming victory, but it was enough for Smith to take a seat in the legislature and to launch her libertarian agenda.

Who is Danielle Smith?

Basic biographical information regarding Smith is readily available. She was born in Calgary on April 1, 1971, the second of five children. Her paternal great-grandfather was Philipus Kolodnicki, a Ukrainian immigrant who changed his name to Philip Smith upon arriving in Canada in 1915. Smith has also claimed Indigenous ancestry, but no evidence exists in support of this contention. Her parents worked in the oil patch. The family lived for a time in subsidized housing.

She completed a B.A. (English) at the University of Calgary, where she met, married, and later divorced Sean McKinsley, and also met such arch-conservatives as Ezra Levant (founder of Rebel News) and Rob Anders (later, a Conservative MP). She subsequently also completed a B.A. in economics, during which time she met political scientist Tom Flanagan who became a kind of mentor to her. He recommended Smith for a one-year internship with the Fraser Institute. By now, she was well on her way to becoming, as she defines herself, a “libertarian populist” whose primary intellectual influences include Friedrich Hayek, Adam Smith, John Locke, and Ayn Rand.

In 1998, Smith was elected a trustee of the Calgary Board of Education. A year later, however, then Minister of Learning Lyle Oberg dismissed the entire board as it had become dysfunctional, of which by her own admission, Smith was a chief cause. Subsequently, Smith worked for the Alberta Property Rights Initiative and the Canadian Property Rights Research Institute, before joining the Calgary Herald as a columnist with the editorial board (where she notoriously did not hesitate to cross the picket line during the 1999-2000 strike at the newspaper). She later succeeded Charles Adler on a Global Television interview show.

She married David Moretta, a former executive with Sun Media, in 2006. That same year, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business hired her as its provincial director for Alberta. Disenchanted with the premiership of Ed Stelmach, she left the PCs and joined the Wildrose Alliance party, becoming its leader in October 2009. The ensuing events—the 2012 election, the floor crossing in 2014—were recounted earlier and are not repeated.

Smith was defeated in her bid for the PC nomination in Highwood on March 28, 2015. Any formal political future for Smith seemed dim. By now, Smith and her husband had moved to High River, a town south of Calgary. They survived the infamous floods of 2013 and in 2018 opened a restaurant, the Dining Car at High River Station (formerly, the Whistle Stop Café). She became a popular talk radio host on Calgary’s QR77 in 2015, a job she held for the next several years, but left in early 2021 citing personal attacks on Twitter.

In 2019, while still a talk show host, she registered as a lobbyist for the Alberta Enterprise Group, an association of which she was also president. The Calgary-based association represents 100 companies involved in such areas as health care, transportation, construction, energy, law and finance. Many of the things Smith has lobbied for in the past—for example, health spending accounts and royalty breaks for energy companies that clean up abandoned wells—she now promotes in her formal political role.

Smith’s occupational career can best be described as that of a serial lobbyist and media personality. Her chief ability seems that of convincing others of her abilities. In politics, however, her ambitions and promise have often fallen short of actual performance. Ideologically, she is a committed right-wing libertarian, for whom freedom trumps equality, markets trump politics, and democracy is little more than an exercise in populist agitation and manipulation. Her actions since becoming premier, in centralizing power within her office, suggests an authoritarian streak.

Smith is a clever wordsmith, and described by many as intelligent, but she has not shown herself to be a critical thinker; instead, she seems wedded to novelty for novelty’s sake. She is generally dismissive of “experts,” except when their ideas validate what she already believes. In the words of journalist Graham Thomson, she is “noted for constructing a world view based on anecdotal evidence, confirmation bias and bad choices.”

Befitting a talk radio host, Smith has a lot of opinions (in an Ask Me Anything broadcast in June 2021, Smith said, “I literally have an opinion on everything”). But her opinions often lack evidence. The examples are multitude. In 2003, while a columnist for the Calgary Herald, she cited tobacco-funded research that “smokers of just three to four cigarettes a day have no increased risk of lung cancer, coronary heart disease, bronchitis or emphysema.” Her particular focus on cancer was repeated during the 2022 leadership race when she implied that everything, up to “stage four and that diagnosis” is completely within an individual’s capacity to control.

In the midst of a massive beef recall due to E. coli contamination in 2012, Smith—at the time, still Wildrose leader—claimed that thoroughly cooking the meat would kill the bacteria, and that it could then be fed to those in need. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she used her radio show, newsletters, and podcasts to criticize health restrictions, and the science behind them, and to promote debunked treatments such as hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, for which the radio station disciplined her.

Smith’s over-the-top rhetoric continued even after winning the UCP leadership. During a media scrum immediately after her swearing-in ceremony as premier, Smith declared the unvaccinated were “the most discriminated against group that I’ve ever witnessed in my lifetime,” having faced “restrictions on their freedoms” based on having made a “medical choice” (critics noted the statement’s ignoring of a host of other groups historically persecuted, imprisoned, and even murdered, and the absence of any consideration of the rights of individuals to safe working environments).

Smith later said she would amend the Alberta Human Rights Act to protect the rights of those refusing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, and mused about a possible “blanket amnesty” for anyone charged with violating public health restrictions. She also accused Alberta Health Services of “manufacturing” staffing shortages and of being in cahoots with the World Economic Forum.

Smith said during the leadership race and after that she would be a “unifier,” a necessary trait given the party’s difficulties during Kenney’s time as premier. Her track record speaks otherwise, however. While she may succeed, where Kenney failed, in unifying the party, the contrary evidence points to a party and a province facing further division.

Conclusion

And so it is that Alberta has as its premier a right-wing libertarian and conspiracist who, despite lacking a personal mandate from the people, is in position, as we write, to attempt remaking the province according to her own fantasy vision of what Alberta is and should be. Will Danielle Smith achieve that mandate in 2023—or sometime thereafter?

Elections are never entirely predictable. The NDP has held a solid lead in the polls for most of the last two years, repeated in polls conducted by Janet Brown and Associates in the fall of 2022. But the UCP cannot be counted out. Resource revenues have again filled Alberta’s coffers, money with which governments can reward friends, make amends to others, and shore up support in key ridings. The habit of voting for conservatives—whatever that term actually means—remains entrenched in Alberta’s political culture; there remain scores of angry and alienated voters for whom the UCP message resonates, especially during a crisis of inflation and affordability that many Alberta have faced throughout 2022, and which Smith has continuously laid at the feet of the federal Liberals and NDP.

Yet, should Smith win, at least one prediction seems safe: That she will—perhaps sooner, perhaps later—disappoint her followers and face a party revolt that will force her from office. The reason is simple. Like all recent conservative premiers, she has promised more than she can deliver.

Kenney, Smith, and the UCP are the symptom of a failure of Alberta’s entrenched political class to deal with the province’s deeper problems. This failure takes the form of demands that the Alberta state be given more power; that is, that those who have held power in the province going on forty years be given even more power. But nothing ever changes. Their fantasy solutions always crash and burn against the political, environmental, social, and economic realities of our time. The years of UCP government represent the thrashings of this old order; the railing of anger and despair against the light.

What Abraham Rotstein said about Canada in 1964—”Much will have to change in Canada if the country is to stay the same”—could be applied to Alberta. It is a great province; but it could be better—it must be better. Abandoning the politics of anger and fear would be a good start.

Trevor Harrison is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Lethbridge. He was formerly Director of Parkland Institute (2011-2021), an Alberta-wide research organization, of which he was also a founding member. He is best known for his studies in political sociology, political economy, and public policy. He is the author, co-author, or co-editor of nine books, numerous journal articles, chapters, and reports, and a frequent contributor to public media, including radio and television.

Anger and Angst is about Jason Kenney, Danielle Smith, and the UCP’s Endless Chaos

Alberta is on the verge of a very important election, featuring an extreme right-populist party—the United Conservative Party (UCP)—versus the New Democrats. Anger and Angst: Jason Kenney’s Legacy and Alberta’s Right examines the chaos of the current UCP Alberta government leading up to the election, and asks why it has happened. Answering these questions, this book leaves the reader with a better understanding of politics, ideology, and the New Right.

Anger and Angst has its origins in the aftermath of the 2019 election. In February 2020, a group of academics and other political observers gathered in Edmonton for a free-wheeling discussion of Alberta’s unfolding political scene. Though no one could predict the twists and turns that followed, it was clear to everyone assembled that Alberta was entering a critical, if uncertain, period of political turmoil. Combining 22 essays on politics, the economy & environment, education, housing, childcare, and right-wing populism, this book critically examines the extraordinary years of the UCP’s time in office, 2019-2023, a period arguably the most chaotic in Alberta’s political history.

At this book’s heart lies an account of how the UCP has governed; the ideas, personalities, and social forces that have driven its agenda. The editors argue that an entrenched elite, based largely in the oil and gas sector, is increasingly fearful of losing its power; fearful, more broadly, of the province that Alberta is struggling to become. In an effort to maintain its power, this elite has constructed an elaborate mythology based on a culture of grievance and victimhood. Given the current national discourse around energy transition and provincial autonomy—and the rise of the populist right across Canada—Anger and Angst will provide valuable insights and information to people both inside and outside of Alberta.

“Illuminating and thought-provoking, Anger and Angst reveals the UCP government’s undemocratic and destructive underpinnings, cuts to educational funding to privatised healthcare to the undermining of workers’ rights. Read this book!”

— Jackie Flanagan (Founder, Alberta Views)

“The United Conservative Party (UCP) is the political vehicle of conservative Albertans who are angry that their worldview and its economic underpinnings in the oil industry are coming apart. If you want to understand “freedom convoys”, anti-lockdown Rodeo rallies, and where their embattled, fortress mentality comes from, read this book. Anger and Angst is a hugely informative, impressive collection, with a very broad reach. The authors have the courage to tell it straight and dig where others accept the surface.”

— Gordon Laxer (Founding Director of Parkland Institute, Political Economist, and Author)

“If you’re wondering WTF is going on in Alberta politics, and how we got here, you really need to read this book. Anger and Angst expertly serves up the chaos and controversy of the Kenney years in bite-sized chapters from some of Canada’s top political writers who explain how a guy in a blue pickup truck ran over a province.”

— Graham Thomson (prominent journalist)

About the editors

Trevor W. Harrison is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Lethbridge. He was formerly Director of Parkland Institute (2011-2021), an Alberta-wide research organization, of which he was also a founding member. He is best known for his studies in political sociology, political economy, and public policy. He is the author, co-author, or co-editor of nine books, numerous journal articles, chapters, and reports, and a frequent contributor to public media, including radio and television.Ricardo Acuña has been executive director of Parkland Institute since 2002. He has a degree in political science and history from the University of Alberta and has over 30 years of experience as a volunteer, staffer, and consultant for various non-government and non-profit organizations locally, nationally and internationally. He has spoken and written extensively on energy policy, democracy, privatization, and the Alberta economy, and is a regular media commentator on public policy issues.

Table of Contents

Notes on Contributors

- Introduction - Trevor Harrison and Ricardo Acuña

POLITICS

- Sorry, Not Sorry: The Nasty, Brutish, and Short Premiership of Jason Kenney - Janet Brown and Brooks DeCillia

- A Window on Jason Kenney’s Fall from Grace - Ricardo Acuña

- The Religious Roots of Social Conservatism in Alberta - Gillian Steward

- Decoding the UCP’s Freedom Mantra - Trevor Harrison

- “We Reject the Premise of Your Question.” The Media and Jason Kenney’s Government - David Climenhaga

ECONOMY AND ENVIRONMENT

- Extraction First: The Anti-Environmental Policies of the UCP Government - Laurie Adkin

- The Future is Past: A Political History of the UCP Energy Policy - Kevin Taft

- Alberta’s Brain Drain Redux: The Migration of Alberta’s Youth Under the UCP - Richard E. Mueller

- Turning the Screws, Turning Back the Clock: The UCP and Labour - Jason Foster, Susan Cake, and Bob Barnetson

- Alberta’s Job Creation Tax Credit: A Hidden Gift to Oilsands Producers - Bob Ascah

PUBLIC SECTOR

- Choice Over Rights: The UCP’s Ultra-Right Vision for Education - Bridget Stirling

- Alberta is Open for Business: The Renewed Push for Health Care Privatization - John Church

- Ground Zero in Canada’s Higher Education Shock Doctrine: UCP Alberta’s Post-Secondary Sector - Marc Spooner

- Subsidized Rental Housing and Homelessness Under the UCP - Nick Falvo

- Early Learning and Child Care: The Role of Government Under the UCP - Susan Cake

SOCIAL ALBERTA

- Dysfunction in the Family: Provincial-Municipal Relations Under the UCP - Ben Henderson

- Back to the Future: The UCP’s Indigenous Policies, 2019-2022 - Yale D. Belanger and David R. Newhouse

- Simply Conservative? Rethinking the Politics of Rural Alberta - Laticia Chapman and Roger Epp

- Pepper-Spray for All: The UCP’s Approach to Countering Race-Based Hate in Alberta - Irfan Chaudhry

- The United Conservative Government, Right-wing Populism, and Women - Lise Gotell

- Conclusion - Ricardo Acuña and Trevor Harrison

2023; 6x9; 534 pages

Anger & Angst Retail Prices

Paperback:

978-1-55164-806-4 $34.99

Hardcover:

978-1-55164-808-8 $74.99

PDF eBook:

978-1-55164-810-1 $11.99