Life in a northern B.C. boomtown

Matt Simmons

Local Journalism Initiative

Fri, June 23, 2023

LONG READ

The town of Kitimat, B.C., is folded into a forested valley, tucked back from where the ocean meets the land at the end of a roughly 100-kilometre long inlet. The hub of the community is a jumbled complex of malls with a handful of shops, restaurants and offices serving the population of around 8,000. You can’t see the ocean from here or the sprawling industrial complexes that crowd the waterfront.

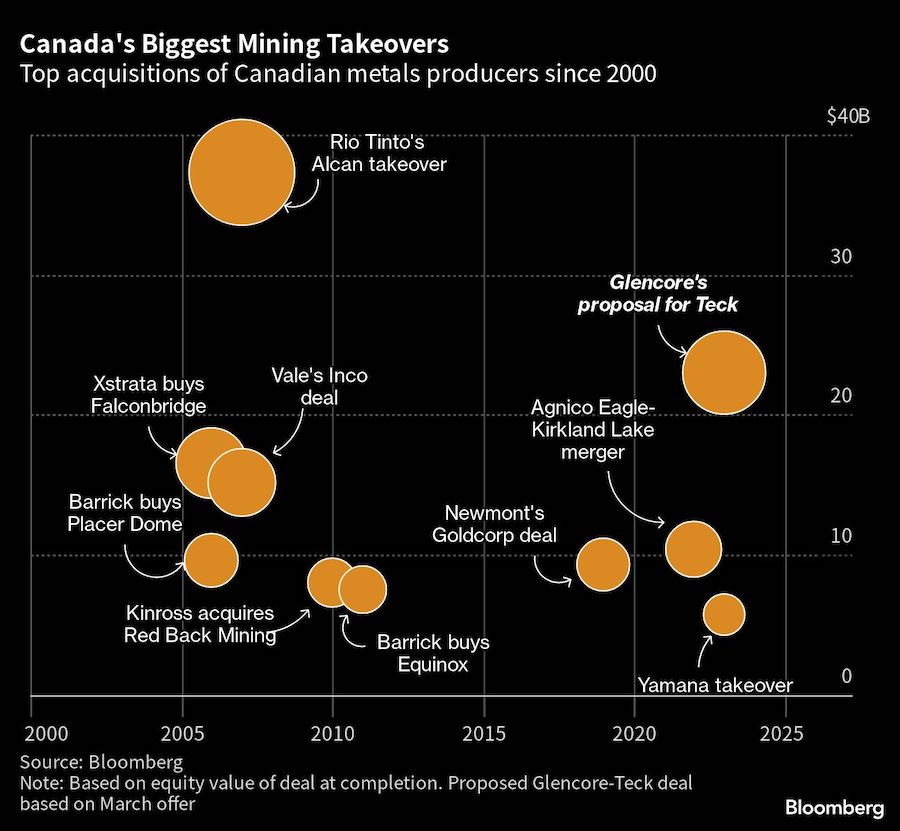

Kitimat was settled on Haisla lands in the 1950s, a planned community built on a promise of prosperity from the Aluminum Company of Canada, also known as Alcan. The town was designed to serve the company’s energy-intensive smelter, which would be powered by a dam built on the other side of a range of snow-capped mountains. Now owned by international mining giant Rio Tinto, the smelter’s smokestacks have been puffing ever since.

Across the harbour from Alcan is Cʼimaucʼa (Kitamaat Village), a reserve home to around 700 members of the Haisla Nation. Nestled along the shoreline directly opposite the industrial complex, the village has had a front-row seat from day one.

Kitimat’s slogan is a “marvel of nature and industry.” But which comes first: nature or industry? Can they exist in harmony? As the community adapts to a burst of new growth linked to LNG Canada, Cedar LNG and other proposed projects, it’s a question the town has to answer, one way or another.

With “Uncle Al,” as it’s known locally, paving the way in the 1950s, other companies saw a chance to capitalize on the industry-friendly town and its access to marine shipping routes. In the 1970s, Eurocan opened a pulp mill a few kilometres up the Kitimat River estuary, and in the 1980s, Methanex started producing and exporting methanol and ammonia from the waterfront. Neither stood the test of time. In 2005, Methanex announced it was shutting down, citing high gas prices. Five years later, Eurocan followed suit. With two of three major employers gone, Kitimat slipped into a period of economic decline.

Then LNG Canada, a joint venture including some of the largest fossil fuel companies in the world, started talking about building its liquefaction facility on the former Methanex site. The promise of good, high-paying jobs fit a familiar narrative of industry taking care of the community. With buy-in from the Haisla elected council and support from the town, the project was approved by the provincial and federal governments in 2016. When the consortium announced a final investment decision in 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called it the largest private investment in Canadian history.

Four years after the first shovel hit the ground, Kitimat is undeniably busier. A continual parade of white work trucks funnels through the town and convoys of shuttle buses ferry workers between job sites and temporary housing. That housing is like a small town, complete with streetlights, roads, restaurants, medical care and other services — all fenced off from the surrounding community.

For more than a decade, the B.C. government has been courting the gas export industry. The province has subsidized LNG Canada and the Coastal GasLink pipeline to the tune of more than $6 billion in tax breaks, incentives and other forms of financial support. The pair of projects will connect rich gas deposits in B.C.’s northeast to overseas markets. Kitimat sits in the middle.

Whether it’s the proverbial boom-and-bust cycle or a different kind of trend, the coastal community is full of anticipation. The Narwhal spent some time in Kitimat hearing from locals what life is like during this period of change. Here are their stories.

Phil Germuth isn’t shy about his support for industry. He grew up in the community and is currently serving his third term as mayor. He said the jobs at the smelter kept the town alive after Methanex and Eurocan shut down, but there were hard times for several years.

“People have said a lot about boom and bust,” he told The Narwhal in the town offices on the top floor of the City Centre Mall. “I would never ever call us ‘bust’ because we’ve had the aluminum industry here for 65 years now. Things were really tough then. The housing market was down and you saw a lot more places starting to look pretty bad.”

“That’s clearly changed,” he added with a smile.

Through an agreement with LNG Canada, the community has received more than $16 million in taxes since 2019 and will get an additional $8 million this year. Once the facility starts operating, the municipality will get $9.7 million annually for the first five years. New houses are being built and old ones renovated. Residents directly inconvenienced by the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which winds its way through suburban neighbourhoods, are financially compensated. Germuth said there’s a “confidence in the community” that hasn’t been felt for more than a decade.

“Families that had to leave after Methanex closed are now coming back, and their kids are now working here,” he said. “I believe the overwhelming majority of Kitimat does support industrial development — when it’s done right.”

But the influx of industry in the community doesn’t mean the “streets are paved in gold,” he added. Many businesses remain boarded up, derelict buildings sit on overgrown lots and housing is a major issue.

“Having that industrial tax base is clearly much more of a benefit than it is a burden, but it does give you unique challenges that nobody else has,” he said, noting as an example local businesses have to offer competitive wages to keep employees happy. “Otherwise they’re all going to leave and go to industry.”

He said the town, like many others in the north, is overdue for major infrastructure updates and the council is trying to balance its priorities during this period of rapid growth.

“We haven’t been able to pave a road now for over two years because we just don’t have that in our budget. We’re trying to do everything else that we have to do.”

The town recently replaced a decades-old bridge over the Kitimat River and is building B.C.’s first 24-hour daycare to support shift workers. A new firehall is on the table as is an upgrade to the swimming pool.

To Germuth, a key success of the LNG Canada project is it strengthened connections between Kitimat elected leaders and Haisla elected leaders.

“The political relationship between the District of Kitimat and the Haisla Nation Council, it wasn’t there, it was terrible,” he said. “LNG Canada came in … and they would bring us into the same meeting. That’s all it really took, was the two councils just hanging out together, getting to know each other at a project that we both support and that we’re both going to be greatly benefiting from.”

He believes the town’s future is promising.

“Kitimat is built on industry. We realize the advantages you have by having industry in your town. Clearly we’re not perfect — we have challenges like everybody else. But if you were to look at most other communities, I would say we’re probably in a little better position.”

A self-described “Saskatchewan farmboy,” Tracey Hittel moved to Kitimat when he was 21 for a job at the methanol plant. He met his wife there and they have two kids together. When the plant shut down, he shifted gears and started up his own businesses — fishing charters, water taxi services and a lodge. He recently handed over the reins after a stint as president of the Kitimat Chamber of Commerce.

“We don’t plan on going anywhere,” he said, driving his boat across the harbour from a small marina while checking his phone for a picture of a halibut he caught a few days before. “It’s pretty easy living here, you know?”

Between Alcan and LNG Canada, there’s almost no access to the water from town. Hittel said that means a lot of the community is disconnected from the ocean and unaware of risks associated with increased marine traffic and disturbance to fish habitat.

“I’ve been doing this for so many years, working at Methanex and then starting my own fishing guiding [business],” he said. “I’ve got to see all aspects of it, from the environmental side and the industry side. Most people are naive. People here don’t understand what’s coming. I would say 80 per cent of the population has never been on the ocean.”

LNG Canada will employ up to 350 people in full-time positions for its first phase of operations. It will also support more in ancillary positions, like tugboat pilots and other related jobs. For example, LNG Canada recently awarded a contract worth more than $500 million to a Haisla-led marine services venture.

Construction jobs have kept the community buzzing for the past few years. In April, there were nearly 7,000 workers in Kitimat building the facility, according to an LNG Canada spokesperson. The majority are employed through the consortium’s engineering, procurement and construction contractor, known by its acronym JFJV, which is not locally owned. Hittel said this means few local businesses have been able to grow as a result of the project.

“One thing I don’t like about what’s happening with these contractors — that money is not staying in the community,” he explained. “It’s not somebody that had the gumption to say, ‘I want to start my own company and start being a supplier to LNG Canada,’ like many young companies have over the years working for Rio Tinto. This opportunity hasn’t really flourished in Kitimat.”

LNG Canada didn’t directly answer questions about how many locals were employed at the project but said less than two per cent of the workers come from outside Canada.

“In both construction and later in operations, LNG Canada is committed to hiring locally first, then within B.C. and Canada,” the spokesperson told The Narwhal in an email. “As of April 2023, LNG Canada and its contractors and subcontractors have awarded more than $4.1 billion in contracts and procurement to businesses in British Columbia.”

The consortium has also invested $5 million in “meaningful trades training and development programs designed to increase the participation of local area residents, Indigenous communities and British Columbians in trades and construction-related activities,” according to LNG Canada.

Hittel said he’s not convinced the project is living up to the promises that were made when the consortium first came to town. On the water, he pointed at the LNG Canada terminal, looming up above his boat.

“All these modules, see them all sitting there? They all have to go on site. They came from ships, they got offloaded and they’ve got to be moved.” He said building the modules overseas and bringing them to Kitimat to be assembled was a lost opportunity for more local jobs.

He added the construction of the liquefaction facility and the pipeline is taking a toll on the town. Between LNG Canada and Coastal GasLink, the number of people in Kitimat has more than doubled.

Though it’s hard to pin down the exact impact these projects — and the shadow population they bring in — have had on local infrastructure, Hittel said everything from roads to water supply have taken a hit.

For all his frustrations, Hittel is decidedly not anti-industry. He just wants his community to fully benefit. He’s doing what he can to make the most of the industrial boom. He noted he’s getting trained in spill response and will be at the Alcan dock that evening.

“Rio Tinto has a ship coming in here at six o’clock tonight,” he said. “What we do for them is when a ship comes in and the ship throws the ropes to the people on shore, we have our boat right there in case someone goes into the drink.”

And when the big LNG carriers start arriving, he’ll be around.

Dustin Gaucher, grandson of the late Wa’xaid Cecil Paul, a revered Xenaksiala Elder who passed away in 2020, stood up from his kitchen table and shook a frog rattle he made. Eyes closed, he boomed out an ancient song.

“When I get my name, this is what I want sung at my feast. All the Kitlope chiefs used to sing this.”

Gaucher lives with his family in a small, expensive rental house in a Kitimat neighbourhood overlooking the town. He has a complicated relationship with his community and ongoing conflict with the Haisla elected council.

His focus right now is on his responsibilities to “wake up” his language and culture and pass it on to youth, he said.

“What I’ve been doing is basically learning everything that we’ve forgotten,” he told The Narwhal, describing his journey with the Haisla language, stories and songs and connections with the land. He credits the teachings of his Elders for guiding him as a child, and now.

“That’s my magic canoe,” he said, pointing to an image painted on a drum he made. “This is the world of the physical realm, so that’s the world we live in and that’s why it has a normal killer whale. And this is the realm of the dead — that’s Wa’xaid’s magic canoe and that’s my baba (grandfather) G’psgolox, Wa’xaid’s brother. That’s them guiding me from the other side in my canoe so I always stay on track.”

In late 2021, when police arrested Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their supporters who were attempting to prevent Coastal GasLink from drilling under the Wedzin Kwa (Morice River), Gaucher and a few others travelled to Gitxsan territory to show solidarity. They were met with heavily armed tactical units of the RCMP.

“We had sniper rifles [aimed at] us,” he said, choking back tears. “I told these officers, ‘This is Canada, you are not allowed to point guns at unarmed civilians.’ ” He said he called them out for “pointing guns at innocent people and children” as helicopters flew over the gas station and an elementary school.

Gaucher said he’s not totally opposed to LNG Canada and Coastal GasLink but he doesn’t stand for colonial violence against Indigenous people. Speaking out publicly alienated him from much of his community, he said, who he described as “too afraid to speak.”

“What’s crazy is being classified as one of those ‘crazy anti-pipeline people’ because not once did I say I was against it,” he said, his fists clenched on the table.

He hopes neighbouring nations would come show their support if Haisla people were subjected to the same treatment as Wet’suwet’en land defenders. What he wants most is to repair what was broken during colonization. He talked about grease trails and how the trade networks connected the Haisla, Xenaksiala, Wet’suwet’en, Nuxalk and others. When Indigenous people across B.C. were moved onto reserves and forced into residential schools, the trails grew over and the connections were severed.

“They’ve trained us to hurt ourselves,” he said. “And then they’ve trained us not to talk to our neighbours, to the neighbours we used to trade with — we’re isolated and we fight amongst ourselves. That’s what my grandfather calls ‘crabs in a bucket.’ ”

He paused and shook his head. “The only destination for it is in your boiling pot on the stove.”

To heal and move forward, the youth need to reconnect with songs, stories and language, he said. Through the youth, those rekindled connections can be brought back to the Elders and to his generation, spreading through the community.

“My whole goal in the long run is to support the youth,” he said, dreaming about bringing ceremony, songs and dances back to Haisla territory. “I want to start dancing them again in our lands — our trees, our plants, they all remember. When we hit our drum, it’s the heartbeat of Mother Earth.”

“The old ways are good. That’s why they’re there.”

As members of a local environmental group, Cheryl Brown and Lucy McRae have been working for years to minimize the impacts of industry and ensure development is done with transparency. They have a good grasp of provincial and federal environmental assessment processes and keep a watchful eye out for potential infractions. They attend municipal meetings and try to keep one foot in the door with industry.

“Kitimat is touted as ‘nature and industry’ but when you listen to most of council and a lot of the chamber of commerce people, they refer to it as industry and nature,” McRae said. “Industry always comes first.”

As they stood chatting with each other on a path that follows Sumgas Creek through the middle of town, a passerby grinned.

“This looks like a regular meeting of the Douglas Channel Watch,” he laughed.

For all its current busyness, it’s still a small town.

The creek is being restored as an offset project. To compensate for damages to fish habitat at the site, LNG Canada is required to complete several restoration projects to previously impacted areas. A series of concrete weirs built decades ago cut off fish access in the Sumgas system. They’re slated for removal, getting the creek closer to its once-natural state. If successful, the restored waterway will see trout and salmon repopulate the heavily disturbed habitat — but Brown and McRae have their doubts.

“This could be a really good news story. It could come out really nice,” Brown said. “The part that wasn’t done properly, though, was they felt there was no need to consult with anyone.”

She said during the environmental assessment process for LNG Canada, there were numerous opportunities for public engagement, ways in which residents could voice their concerns or get answers to questions. But since the project’s approval, that dynamic has changed.

“As soon as the decisions were made, it was just like,” Brown made a slicing motion, “cut off. We’re always scrambling, trying to figure out what’s going on. It’s really difficult to get the full story.”

LNG Canada told The Narwhal it established a quarterly “environmental forum” in 2019 to “inform and engage with local environmental organizations” — including Douglas Channel Watch. A spokesperson said its contractor, JFJV, sends regular notices and invitations directly to the environmental group and others for public engagement opportunities.

The goal of the group is to hold companies like LNG Canada and Coastal GasLink accountable and make sure they’re playing by the rules. Brown said she wishes the pipeline company listened to locals more, noting a section of the route flooded in the fall of 2020, stranding heavy equipment for days. Brown and McRae gestured to the creek and said everyone knows the river and its tributaries regularly flood — Kitimat gets a lot of rain.

They recently managed to meet with the council to discuss the pair of projects and to share information. They were visibly relieved as they told The Narwhal the most recent meeting went well.

“As groups, we’ve been working towards working better with council,” McRae said. “They are willing now to sit down with all the groups and listen to concerns.”

She insisted they’re not coming from a position that shuns industrial development. After all, without Uncle Al, the community wouldn’t exist.

“My biggest concern is everything is for export,” McRae said. “Can we manufacture more stuff here? Once this project is finished and everybody who’s renting houses in town leaves, this town is in big trouble.”

“For me, it’s about the environment,” Brown said. “Maintain the integrity of the land base, the biodiversity. There are huge opportunities here to do this right — and the window is closing.”

For Nick Markowsky and Brandon Highton, opening a brewery in Kitimat was more than an entrepreneurial leap paired with a love of craft beer. Growing up in the town and knowing what it has to offer, especially in terms of access to outdoor recreation, they wanted to help Kitimat’s identity evolve.

“My background is my grandfather came here in the ’50s for Alcan,” Markowsky said, leaning on the bar of the recently opened brewery. “I moved away for a fair bit of time, went to school and kind of just lived all across Western Canada, and missed what Kitimat has to offer and being close to family and friends.”

Like many others who’d left the community, he came back to a job working on Rio Tinto’s smelter modernization project, a $4.8-billion expansion that was completed in 2015.

“It’s been nice to get back into the lifestyle,” he said. “I love knowing that I can walk into the bush and disappear.”

Markowsky said part of the vision behind the brewery was “trying to get away from it just being an industrial town with services being provided to industry.”

“The biggest thing that we, as born-and-raised Kitimat guys, want to share and promote is growth outside of industry,” he explained. “More being given back or produced for the community and less about industry, industry, industry.”

That doesn’t mean, of course, that their business isn’t serving industry workers as well. In the evenings, the parking lot is full of work trucks. Inside, high-visibility vests and steel-toed boots look very much at home in the warehouse-like building. But, as Highton explained, working with the district on the project and building a brand new space in the heart of the community has a knock-on effect.

“They had this downtown revitalization plan that we’ve heard about for years and years, but we’ve never really seen anything be developed down here,” he said.

Since opening in April, they’ve been hearing from people about a desire to see Kitimat invest in infrastructure like more biking and walking paths, green space and other ways to improve quality of life in the community.

“With us going up, we’re starting to see them put more work into developing some of these spaces, starting to pretty up this town because we are a bit dated in some areas,” Highton said. “It’s time for us to get a bit of a refresh here.”

Matt Simmons, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Narwhal

https://www.britannica.com/place/Kitimat

3 days ago ... Kitimat, district municipality, on the west coast of British Columbia, Canada. It lies at the head of the Douglas Channel, a deepwater fjord ...